T

o the E

ditor: From 1999 to 2014, suicide rates in the United States surged to high levels (

1), and researchers in the United States have suggested that the availability of psychiatric beds may be a risk factor for suicide in the country (

2). Mental health services in Hong Kong have been evolving over the last two decades, and there has been a 40% reduction in the provision of psychiatric beds (

3). Whether the decline in psychiatric beds was associated with an increase in suicide rate in the territory was not known. We used population-based data over the past 16 years to explore the relationship between psychiatric beds and suicide rates, as well as unemployment rates.

We obtained population-based data from the Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department (

4), the Hong Kong Hospital Authority (

5), and the Hong Kong Jockey Club Center for Suicide Research and Prevention (

6) on unemployment rates, population, psychiatric beds, and suicides from 1999 to 2015. The annual changes in unemployment rates, psychiatric beds, and suicide rates were calculated from 2000 to 2015. Data are exempt from approval by an institutional review board because all records are de-identified and no consent is required.

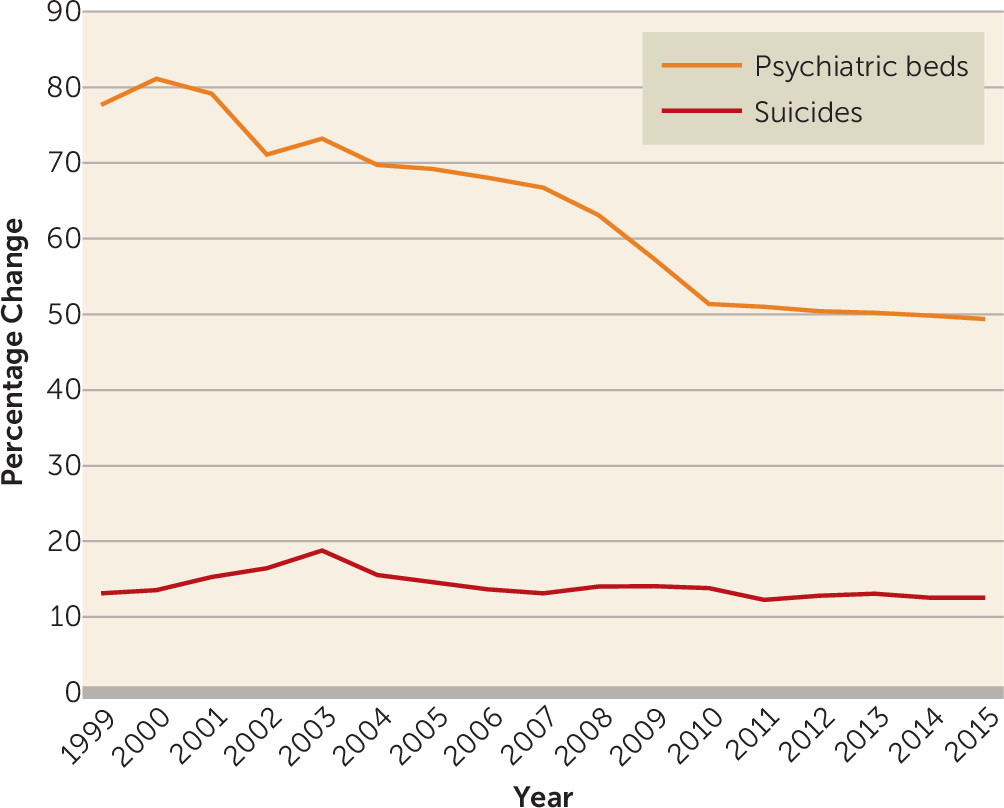

There was a 4.6% decrease in the suicide rate, from 13.1 suicides per 100,000 residents in 1999 to 12.5 suicides per 100,000 residents in 2015, with the highest rate of 18.8 suicides per 100,000 residents in 2003 (

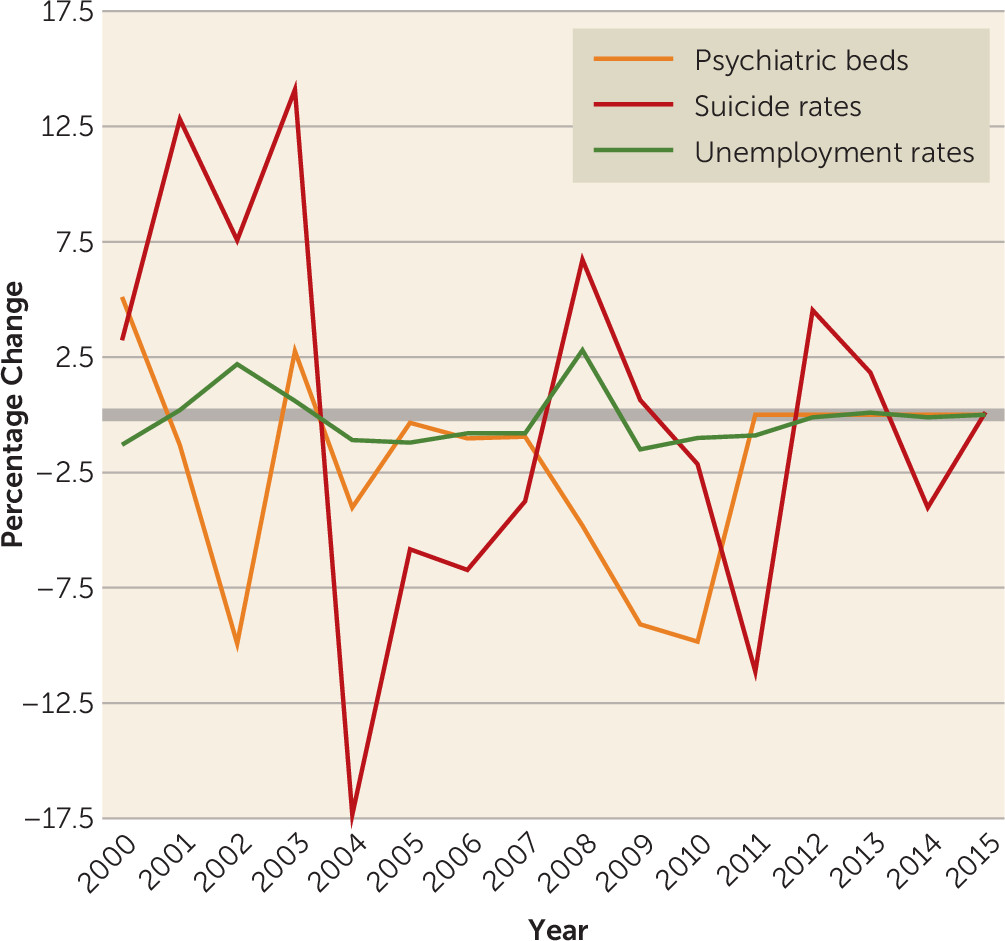

Figure 1). There was no association between changes in the number of psychiatric beds and changes in suicide rates (r=0.055; p=0.841). However, we found a significant moderate positive association between changes in unemployment rates and changes in suicide rates (r=0.58; p=0.019), indicating a 0.58% increase in the suicide rate for every percentage increase in the unemployment rate (

Figure 2).

We did not find an association between changes in the number of psychiatric beds and changes in suicide rates. The reduction in the provision of psychiatric beds may not indicate a decrease in care of individuals at risk for suicide if sufficient community care has been provided and if inpatient services for individuals in need can be arranged. On the other hand, we found that changes in unemployment rates were associated with changes in suicide rates. Unemployment can be a cause of financial stress, which may lead to difficulties in life and suicide risk. The association may also be explained by unemployment being a consequence of mental or general medical illness, which may also be associated with suicide risk.

Our findings suggest that unemployment rates may be an important factor to examine when studying changes in suicide rates. In view of the importance of the social and financial roles of employment in an individual’s well-being, future exploration into the potential effects of psychological and social support should be considered so that intervention and prevention can be undertaken at individual and society levels.