Early Intervention in Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

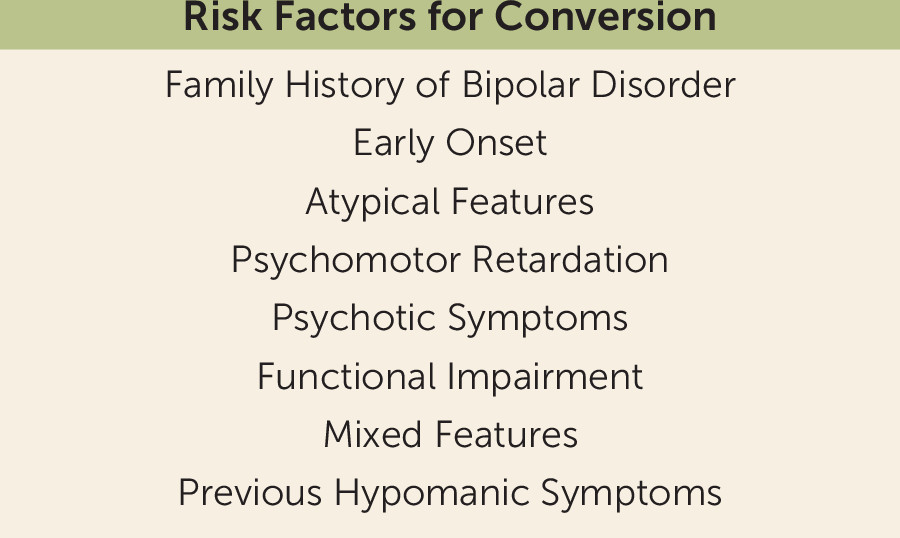

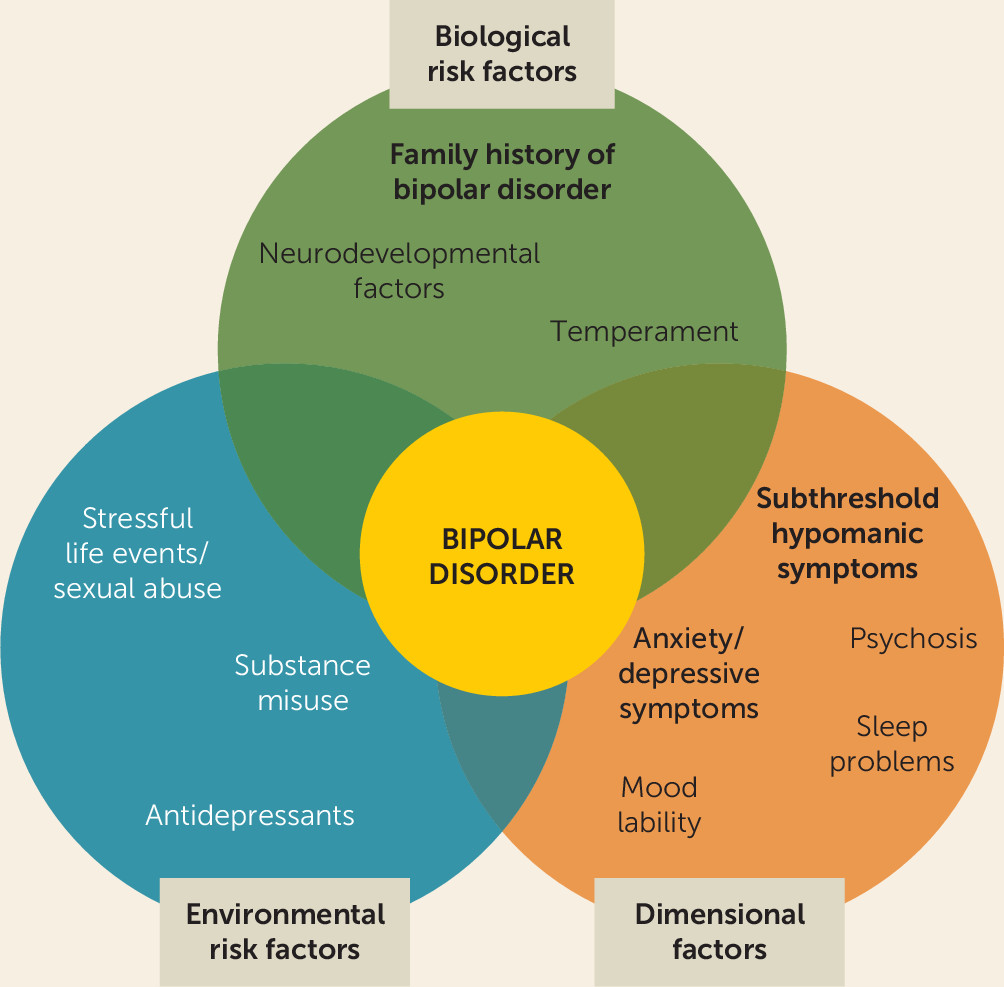

Identifying Risk Factors and Prodromal Symptoms as Predictors of Bipolar Disorder Onset and Course

Environmental Risk Factors

Biological Risk Factors

| Characteristic | Bipolar Disorder Prodromal Stage | Psychosis Prodromal Stage (145, 157) |

|---|---|---|

| Main risk factor | Family history of early-onset bipolar disorder | Family history of psychosis |

| Early symptoms | Subjective sleep disturbances, anxiety, depression | Attention problems, depression, anxiety, avolition, social difficulties, disorganization, sleep disturbances |

| Proximala symptoms | Subthreshold (hypo)manic symptoms | Subthreshold psychotic symptoms |

| Neurodevelopmental profile | Superior or low premorbid cognitive functioning | Verbal memory and processing speed deficits |

Prodromal Symptoms

| Authors | Mean Follow-Up | N at Baseline (M/F) | Mean Age at Baseline (years) | Offspring Sample Description | Main Objectives | Assessment Tools | Conversion Rate to BSD | Main Findings | Offspring Exclusion Criteria | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study | |||||||||||

| Axelson et al., 2015 (49) | 6, 8 years | BO: 391 (200/191), CO: 248 (114/134) | BO: 11.9 (SD 3.7), CO: 11.8 (SD 3.6) | Offspring of patients with BD I or II | To study diagnostic differences between BO and CO; to describe the developmental trajectory of mood episodes and identify diagnostic precursors of full-threshold BD in BO | SCID, K-SADS-PL; subthreshold (hypo)mania was diagnosed using the BDNOS criteria from the COBY study, FH-RDC, the Hollingshead scale (SES) | 9.2% | There was a higher prevalence of BSD and MDE in BO as compared with CO. Nearly all non-mood axis I disorders were more prevalent in BO than in CO. Mania/hypomania was almost always preceded by mood and non-mood disorders. Distinct subthreshold episodes of (hypo)mania were the strongest predictor of progression to full threshold mania/hypomania in BO. | Mental retardation | The information collected for the interval between evaluations was retrospective; most offspring were not through the age of risk for onset of BD at their last assessment; low conversion rate; only a small proportion of the biological coparents had direct diagnostic interviews. | |

| Levenson et al., 2015 (56) | Not stated | BO: 386 (190/196), CO: 301 (144/157) | BO: 11.4 (SD 3.6), CO: 11.0 (SD 3.5) | Offspring of patients with BD I or II | To evaluate baseline sleep and circadian phenotypes in BO and CO; to evaluate whether baseline sleep and circadian phenotypes in the BO are associated with future conversion to BD | SCID, K-SADS-PL; subthreshold (hypo)mania was diagnosed using the BDNOS criteria from the COBY study, PDS, Tanner stages, Hollingshead scale (SES), SSHS | Not stated | Conversion to BSD among BD was significantly predicted by parental and child ratings of child frequent nighttime awakenings, by parental ratings of inadequate sleep, and by child report of time to fall asleep on weekends. | Mental retardation | Use of questionnaire-based proxy measures of sleep and circadian phenotypes; long average time span between baseline SSHS and conversion to BD; low conversion rate; cross-sectional nature of the analyses. | |

| Hafeman et al., 2016 (45) | Not stated | BO: 359 (176/183), CO: 220 (99/121) | BO: 11.6 (SD 3.6), CO: 11.7 (SD 3.4) | Offspring of patients with BD I or II | To assess dimensional symptomatic predictors of new-onset BSD in BO | FH-RDC, SCID, K-SADS-PL, CALS, CBCL, CADS, CHI, DBD, MFQ, SCARED, Hollingshead Four-Factor Index (SES); subthreshold (hypo)mania was diagnosed using the BDNOS criteria from the COBY study | 14.7% | The most important prospective dimensional predictors of new-onset BSD disorders were anxiety/depressive symptoms (baseline), affective lability (baseline and proximal), and subthreshold manic symptoms (proximal). There was an increased risk of new-onset BSD with earlier parental age at mood disorder onset. | Mental retardation | Follow-up visits every 2 years; low conversion rates; not all offspring were through the age of risk for onset of bipolar illness at their last assessment. | |

| Dutch Bipolar Offspring Study | |||||||||||

| Mesman et al., 2013 (52) | 12 years | BO: 108 (58/50) | BO: 16.5 (SD 2.00) | Offspring of parents with BD I or II and age 12 to 21 years | To provide data on the onset and developmental trajectories of mood disorders and other psychopathology in BO | K-SADS-PL, SCID | 13% (3% BD I) | 72% of BO developed psychopathology. In 88% of offspring with a BSD, the index episode was an MDE. In total, 24% of offspring with a UMD developed a BSD. Mood disorders were often recurrent, with high comorbidity rates, and started before age 25. | Children with a severe physical disease or disability or with an IQ below 70 | Small sample size; low generalizability to populations without familial risk; no control group; no data on prepubertal and early adolescent disorders or episodes; not assessing for BDNOS. | |

| Mesman et al., 2017 (61) | 12 years | BO: 107 (57/50) | BO: 16 (range 12–21) | Offspring of parents with BD I or II and age 12 to 21 years | To identify early symptomatic signs of BD in BO with a history of mood disorder (any mood disorder group); to explore the early symptomatic signs of first mood episode development in BO without a history of mood disorder (no mood disorder group) | K-SADS-PL | 2.6% (BD II) in the no mood disorder group, 34% (BD I and II) in the any mood disorder group | Subthreshold manic symptoms were the strongest predictor of BD onset in the any mood disorder BO group. Subthreshold depressive symptomatology was associated with first mood disorder onset. | Children with a severe physical disease or disability or with an IQ below 70 | Small sample size; low generalizability to populations without familial risk; only the baseline screen items of the K-SADS-PL were used. | |

| Canadian Bipolar Offspring | |||||||||||

| Duffy et al., 2013 (54) | 6.23 years | BO: 229 (93/136), CO: 86 (36/50) | BO: 16.35 (SD 5.34), CO: 14.71 (SD 2.26) | Offspring with only one parent with a diagnosis of BD I or II and no other major psychiatric comorbidity | To describe the cumulative incidence of anxiety disorders in BO compared with CO; to identify predictors of anxiety disorders in BO; to determine the association between antecedent anxiety disorders and subsequent mood disorders in BO | K-SADS-PL, HARS, SCAS, Hollingshead SES scale, EAS, CECA.Q | 14% | The cumulative incidence of anxiety disorders was higher and occurred earlier in BO compared with CO. High emotionality and shyness increased the risk of anxiety disorders. Anxiety disorders increased the adjusted risk of mood disorders. | Not stated | Low conversion rate; anxiety disorders preceded mainly MDD; some BO were affected with a mood diagnosis before completing the temperament measure; some offspring were not through the age of risk for onset of bipolar illness at their last assessment. | |

| Duffy et al., 2014 (38) | 6.29 years | BO: 229 (92/137), CO: 86 (36/50) | BO: 16.35 (SD 5.34), CO: 14.71 (SD 2.25) | Offspring with only one parent with a diagnosis of BD I or II and no other major psychiatric comorbidity | To estimate the differential risk of lifetime psychopathology between BO and CO; to compare the clinical course of mood disorders between BO subgroups (defined by the lithium response of the parent) | K-SADS-PL, HARS, SCAS, Hollingshead SES scale, EAS, CECA.Q | 13.54% | The adjusted cumulative incidence of BD was higher in BO than CO. There were no differences in lifetime risk of mood disorders between BO subgroups, except for schizoaffective disorder (all cases occurred in BO of lithium nonresponder parents). | Not stated | Retrospective data collection in some offspring; difficult to mask to family affiliation. | |

| Other offspring cohorts | |||||||||||

| Akiskal et al., 1985 (53) | 3 years | BO: 68 (39/29) | Not stated | Individuals with a parent or older sibling with BD I, less than 24 years old at intake, and looking for clinical attention within approximately 1 year of onset of psychopathologic manifestations | To chart the prospective course of early manifestations in the referred juvenile relatives of known bipolar adults | MCDQ, the Washington University schema | 57% | Acute depressive episodes and dysthymic–cyclothymic disorders are the most common psychopathologic features in the BO. Manic onset occurred after age 13. | Any first-degree relative with schizophrenia | No control group; influence of age at onset of parental illness and type of parental illness not assessed. | |

| Carlson et al., 1993 (51) | 3 years | BO: 125, CO: 108 | BO: 7–16 years | Children of parents with BD | To examine the relationship between attention and behavioral disorders in childhood and subsequent BD | Pupil Evaluation Inventory–Peers, ASSESS-Peers, DBRS- Teachers, DBRS- Mother and Father, the distractibility index of the digit span task, SADS-L, SCID (DSM-III), Social and Occupational Competence, GAS, bipolarity rating, SUD rating | 4.8% | In childhood, mild to moderate attention and behavior problems were significantly more frequent in BO than in CO. In young adulthood, fewer than half of the BO were free of significant psychopathology. | Not stated | Not stated | |

| Egeland et al., 2012 (50) | 16 years | BO: 115, CO: 106 | Not stated | BO from the CARE study in preschool or in school (younger than 14 years old) | To identify the pattern and frequency of prodromal symptoms/behaviors associated with onset of BD I during childhood or adolescence | CARE Interview instrument | 7.8% (BD I) | Higher conversion rates among BO. BO who converted to BD I showed a higher frequency of sensitivity, crying, hyperalertness, anxiety/worry, and somatic complaints during preschool years and of mood and energy changes, decreased sleep, and fearfulness during school years. | Small sample size; nonstandard interview instrument | ||

Helping Prediction of Bipolar Disorder Onset Through Screening Tools

Helping Prediction of Bipolar Disorder Onset Through Biomarkers

Neuroimaging Biomarkers

Peripheral Biomarkers

Behavioral Biomarkers

Exploring Early Treatment Strategies in Bipolar Disorder

Summary and Future Directions

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Keywords

Authors

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).