Gestational diabetes mellitus is a complication of pregnancy, defined as carbohydrate intolerance with onset or recognition during pregnancy (

1). It can lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, neonatal hypoglycemia, and macrosomia (

2). In 2010, the estimated prevalence of gestational diabetes in the United States ranged between 4.6% and 9.2% (

3). Up to 50% of women with gestational diabetes develop type 2 diabetes mellitus in the decades following pregnancy (

4), a risk more than seven times greater than that among women without gestational diabetes (

5). Many risk factors for gestational diabetes are similar to those for type 2 diabetes, including older age, nonwhite race, and obesity (

2,

6).

There is a well-recognized association between treatment with some atypical antipsychotic medications and metabolic side effects, including weight gain and diabetes, in the general population (

7–

11). In 2003, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration required all manufacturers of atypical antipsychotics to add to their labels a warning about the risk for hyperglycemia and diabetes. However, the metabolic safety of antipsychotic drugs for pregnant women, who are already predisposed to insulin resistance (

12), is not fully understood. A small number of studies and case reports have suggested that there is an increased risk of developing gestational diabetes with antipsychotic use during pregnancy (

13–

16); however, no association has been reported in more recent studies (

17,

18). Furthermore, although there are differences in the severity of metabolic side effects between antipsychotic drugs (

19) and biochemical evidence explaining such differences exists (

20), data on the comparative risk of gestational diabetes are scarce (

21).

Psychiatric disorders that are treated with antipsychotic medications, such as bipolar disorder, are often recognized during the reproductive age range (

22) and have a significant impact on the health and wellness of female patients around the time of pregnancy (

23). Despite limited safety information regarding the use of antipsychotic drug treatment during pregnancy, an increasing number of women of reproductive age are treated with antipsychotics in the United States (

24–

26). For some women, treatment continuation during pregnancy is necessary to prevent the sequelae of untreated mental illness (

4), whereas for others, clinicians must weigh the risks and benefits of continuing treatment and may consider either discontinuation or switching to an alternative treatment. Understanding the potential risk of developing gestational diabetes and how this risk may vary by the type of antipsychotic used is an important consideration for patients and clinicians. To assess the risk of gestational diabetes associated with a particular drug, previous studies compared pregnant women who were treated with antipsychotics during pregnancy with women who were not (

15–

18). Such a design is prone to confounding by indication, because women who do not take antipsychotic medications around the time of pregnancy differ in many ways from women who require antipsychotic treatment. These differences, such as having a healthier lifestyle and diet patterns, might affect the risk of developing gestational diabetes. In a nationwide cohort of pregnant women who were all treated with antipsychotic medications before the start of pregnancy, we compared the risk of developing gestational diabetes between women who continued antipsychotic treatment during pregnancy and women who discontinued treatment before the start of pregnancy.

Results

Among 1,543,334 linked pregnancies in the Medicaid Analytic eXtract, we identified 1,924 women who met our inclusion criteria with a filled prescription for aripiprazole during the 3 months before their last menstrual period, 673 with a filled prescription for ziprasidone, 4,533 with a filled prescription for quetiapine, 1,824 with a filled prescription for risperidone, and 1,425 with a filled prescription for olanzapine. In the first exclusion step, the proportions excluded with preexisting diabetes were 4.9% for aripiprazole, 6.5% for ziprasidone, 4.6% for quetiapine, 5.3% for risperidone, and 4.5% for olanzapine (for further details, see Figure S2 in the

online data supplement). Depending on the drug, 19.7%–34.0% of women continued treatment during the first half of pregnancy (

Table 1). Across most of the antipsychotic groups, continuers were slightly older and in some groups showed slightly greater use of other psychotropic medications. Continuers in all groups except quetiapine and risperidone were more likely to have a diagnosis of obesity, and continuers in all groups had received treatment with antipsychotics for a longer duration before their last menstrual period (for further details, see Table S1 in the

online data supplement). After propensity-score weighting, most of the patient characteristics were well balanced between the continuers and discontinuers, with the exception of a few salient covariates, such as obesity and bipolar disorder, which remained slightly unbalanced between olanzapine continuers and discontinuers (

Table 1) (also see Table S2 in the

online data supplement).

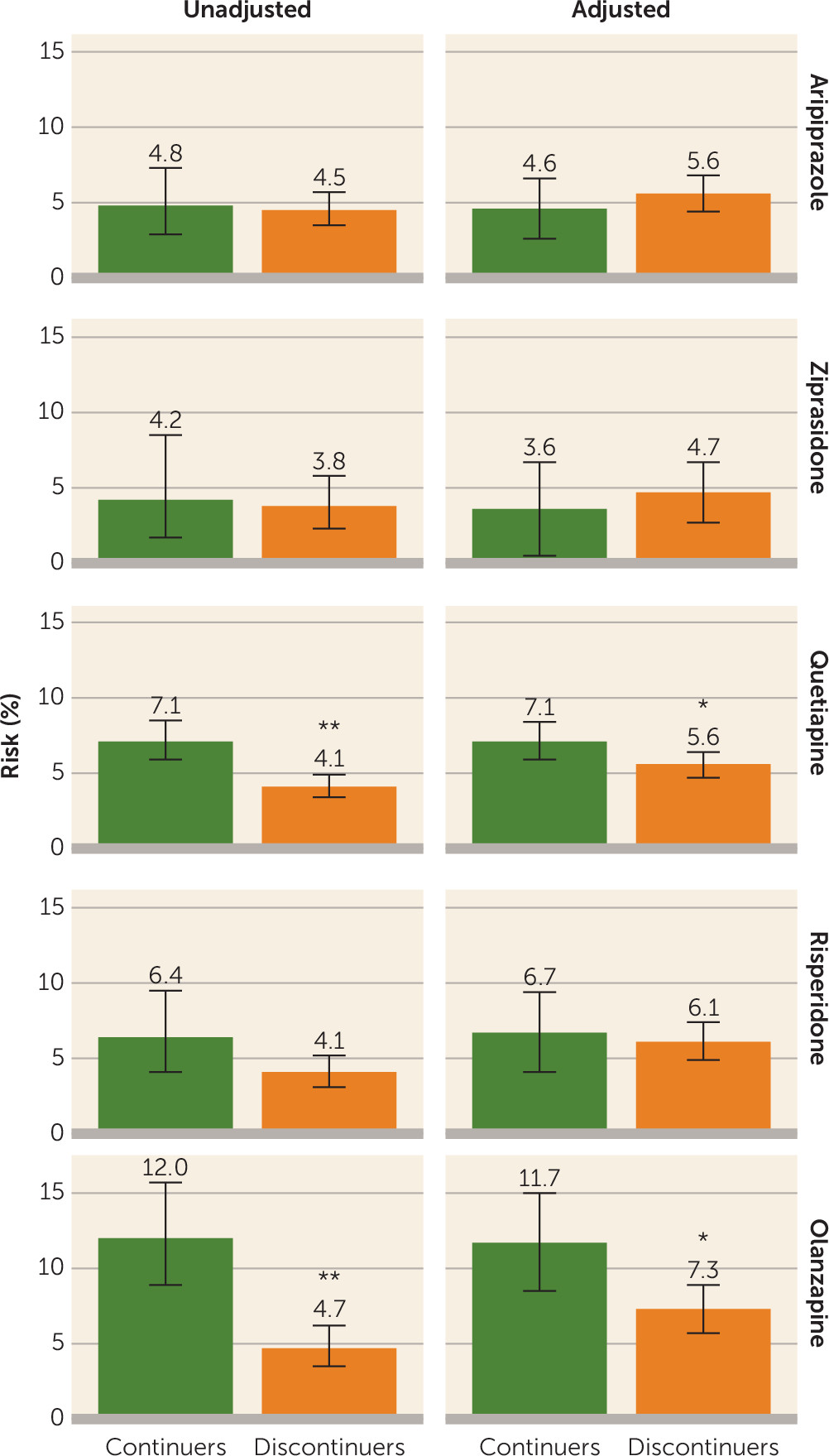

The absolute risk for gestational diabetes ranged from 4.2% to 12.0% among continuers and from 3.8% to 4.7% among discontinuers (

Table 2 and

Figure 1), depending on the drug assessed. The unadjusted relative risk for gestational diabetes associated with continuing treatment during the first 140 days of pregnancy was 1.06 (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.65, 1.72) for aripiprazole, 1.12 (95% CI=0.48, 2.61) for ziprasidone, 1.75 (95% CI=1.36, 2.24) for quetiapine, 1.56 (95% CI=0.98, 2.49) for risperidone, and 2.55 (95% CI=1.73, 3.74) for olanzapine (

Table 2). There was evidence for an elevated risk for gestational diabetes after confounding adjustment for olanzapine (adjusted relative risk=1.61 [95% CI=1.13, 2.29]) and quetiapine (adjusted relative risk=1.28 [95% CI=1.01, 1.62]) but not for aripiprazole (adjusted relative risk=0.82 [95% CI=0.50, 1.33]), ziprasidone (adjusted relative risk=0.76 [95% CI=0.29, 2.00]), and risperidone (adjusted relative risk=1.09 [95% CI=0.70, 1.70]). In a dose-response analysis, the risk increased with increasing cumulative dose of olanzapine until approximately 700 mg and plateaued thereafter (

Figure 2). No clear trajectory was observed for the other antipsychotics considering the width of the confidence band.

The adjusted relative risks in the low-risk (aripiprazole, ziprasidone), medium-risk (risperidone, quetiapine), and high-risk (olanzapine) groups were 0.91 (95% CI=0.60, 1.39), 1.37 (95% CI=1.12, 1.69), and 1.61 (95% CI=1.13, 2.29), respectively. Additional results for the group-level analyses are presented in

Figure 3 (for further details, see Table S3 in the

online data supplement). Across the different analyses, the risk for gestational diabetes appeared to be elevated among continuers compared with discontinuers in the high-risk and medium-risk groups but not in the low-risk group. However, the effects were less precisely estimated in some of the analyses due to the reduced sample size.

The bias analyses illustrated that with an overall obesity prevalence of 62% among women observed in the Massachusetts General Hospital registry who were treated with atypical antipsychotics, the absolute difference in the prevalence of obesity between continuers and discontinuers would have to be more than 25% for the observed relative risk of 1.61 among women treated with olanzapine to be completely attributable to residual confounding (

Figure 4A) (also see Table S4 in the

online data supplement). To put this into context, a 25% difference would mean that 80% of continuers and 55% of discontinuers would be obese patients, with all other covariates balanced between the two groups. Among women treated with quetiapine, the difference would have to be greater than 20% (

Figure 4B) (also see Table S4 in the

online data supplement). If, in contrast, there were more obese women among discontinuers than among continuers, the obesity-adjusted relative risks would be higher than what we observed for both olanzapine and quetiapine. However, if we assume the relative risks to be closer to the lower bounds of each confidence interval, confounding due to smaller differences in obesity could explain the increased relative risk.

Discussion

Among pregnant women who were treated with an atypical antipsychotic before the start of pregnancy, continuation of treatment throughout the first half of pregnancy was associated with a moderate increased risk for gestational diabetes with olanzapine and quetiapine. We did not observe evidence of an increased risk among women who continued treatment with aripiprazole, ziprasidone, or risperidone. Multiple analyses consistently showed a stronger association with olanzapine. Furthermore, there was evidence of a cumulative dose-response relationship with olanzapine.

It is important to consider alternative explanations for these findings, as warranted for any observational study. The main concern pertaining to this study is potential residual confounding by factors not captured comprehensively in the data, particularly obesity. Through formal bias analyses, we demonstrated that the imbalance in the obesity prevalence between treatment continuers and discontinuers would have to be very high (i.e., 20%−25%) after accounting for all other covariates to fully explain the observed risk. Although this possibility cannot be excluded, it seems unlikely given that all of the women were treated with an atypical antipsychotic before the start of pregnancy and we accounted for a broad range of proxy variables. The prevalence of preexisting diabetes and risk factors tended to be higher with ziprasidone and lower with olanzapine, which suggests that the prescribing of antipsychotics may be somewhat selective with respect to such factors. Alternatively, this finding may be explained by depletion of the most susceptible women, who could have developed diabetes after initiation of olanzapine and before their last menstrual period and were excluded from our cohort, leaving for inclusion women with a lower baseline risk who continued treatment. Despite having fewer documented baseline risk factors for developing gestational diabetes, olanzapine continuers had the highest absolute risk for gestational diabetes compared with women who continued treatment with antipsychotics that are less likely to cause significant weight gain. Our findings are consistent with prior knowledge that olanzapine induces the most weight gain among the five study drugs (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone) (

7,

21), which provides a plausible mechanism for the observed elevation in risk among women who continued treatment with this medication. Although quetiapine was associated with a small increased risk for gestational diabetes in this study, risperidone, which is similarly associated with modest weight gain (

21), was not. Use of low-dose quetiapine for insomnia is well known, and women without psychiatric disorders who are treated with quetiapine for insomnia before the start of pregnancy may be more likely to discontinue after becoming pregnant. While this possible scenario could have resulted in confounding in the main quetiapine analysis, restricting the analysis to women with a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder showed nearly identical results. Further research is needed to confirm this finding.

Only a few studies have investigated the association between antipsychotic exposure during pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes, and even fewer have considered specific drugs. By using the Swedish National registries, Reis and Källén (

16) observed an increase in the risk for gestational diabetes (odds ratio=1.78 [95% CI=1.04, 3.01]) among women who self-reported any antipsychotic use during early pregnancy, and Bodén et al. (

15) reported that women who were treated with olanzapine or clozapine during pregnancy had a higher risk for gestational diabetes (odds ratio=1.94 [95% CI=0.97, 3.91]) compared with women who were not treated with either drug. In a high-dimensional propensity-score-matched cohort comprising Canadian women, Vigod et al. (

17) did not observe an increased risk for gestational diabetes among women who were treated with any of the antipsychotics assessed (relative risk=1.10 [95% CI=0.77, 1.57]) or in a specific analysis of women who were treated with olanzapine (N=166). Unlike in our study, the three aforementioned studies included women who were unexposed to antipsychotics as a reference group, a population less comparable in terms of health status and illness severity than discontinuers, and these studies did not exclude women with preexisting diabetes. The higher relative risks in the Swedish studies may be partly due to the fact that they adjusted for only a small number of confounders. The absolute risk among the unexposed women in the Vigod et al. (

17) study was higher than the absolute risk among the discontinuers in our study (6.2% compared with 4%−5%), which implies significant difference in the baseline risk among the two study populations and potentially why we observed different results. In a recent study (

18), women who were treated with antipsychotics during early pregnancy were compared with women with psychiatric disorders who were not treated with antipsychotics to increase the comparability of the groups, under the assumption that other psychotropic medications do not affect the risk of gestational diabetes. However, the sample size was insufficient to consider individual antipsychotics, and specific antipsychotics may have differential effects on the risk of gestational diabetes.

Our study has several strengths. The study population was taken from the nationwide Medicaid program, which finances close to 50% of all pregnancies in the United States (

40). Moreover, Medicaid finances 80% of all antipsychotic prescriptions and 36% of all treatment costs for gestational diabetes in the United States (

41,

42). To define exposure, we used automated dispensing records, which are free of recall bias, and a validated outcome definition. To our knowledge, this study is one of the largest studies of women who continued antipsychotic treatment during pregnancy, and we were able to investigate individual drug effects rather than a drug-class effect.

However, our study is not without some limitations. It is possible that residual confounding due to unmeasured or poorly measured factors, such as lifestyle factors, occurred. Yet comparing treatment continuers with discontinuers rather than with persons unexposed to antipsychotics alleviates this concern because discontinuers are likely to be more similar to continuers than to a group unexposed to antipsychotics. In addition to conducting a formal bias analysis, we showed that adjusting for a large number of empirically identified confounders that may serve as proxies for unmeasured or poorly measured confounders does not change the findings. We could not fully adjust for the duration of antipsychotic exposure, which may have extended many years before recording was conducted in our database. However, adjusting for the treatment duration during the year before pregnancy provided consistent results. We do not have data on the reasons for discontinuation of treatment, which may be associated with illness severity or indication for antipsychotic treatment not recorded in our data. However, illness severity seems unlikely to explain the observed associations, since we observed an increased risk only for gestational diabetes with use of selected antipsychotics. A pharmacy-dispensing record does not guarantee the actual intake of a specific drug. However, by requiring at least two prescriptions during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, we were fairly confident that the continuers in our study actually took the prescribed medication.