Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior have shown dramatic increases in the past decade (

1,

2). From 2007 to 2015, the adolescent suicide rate increased 30% among males and doubled among females, making suicide the second leading cause of death in this age group (

1,

2). Parallel increases have been reported in emergency department visits for adolescent self-harm behavior, which showed an annual rate of increase of 5.7% from 2009 to 2015, with the greatest increases among younger adolescent females (

3,

4).

The standard of care is to hospitalize adolescents who are deemed to be at highest imminent risk for a suicide attempt (

5,

6). However, the risk for suicidal behavior after discharge from the hospital is extraordinarily high (

7,

8), and currently there are no interventions designed to decrease the risk of suicide attempt during this high-risk time, which encompasses the transition from inpatient to outpatient care (

9).

Researchers have developed interventions for suicidal adolescents that include distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and safety planning, with some promising results (

10–

15). Nevertheless, in spite of specialized interventions designed to target suicidal behavior, a large proportion of suicidal events (i.e., increase in suicidal ideation or suicide attempt) occur within the first 3 weeks of outpatient treatment following hospital discharge (

16,

17), meaning that even rapid referral to outpatient care may only partially obviate the high rate of suicidal behavior after hospital discharge. Because suicidal events commonly occur early in outpatient care following hospitalization, one possible strategy for reducing the risk for these early events is to provide an intervention during hospitalization designed to protect suicidal patients as they transition to outpatient care (

15).

To address this critical gap in clinical care, we developed and tested a brief inpatient intervention designed to decrease the risk of suicide attempts following hospital discharge. Here, we report the results from a two-site, treatment-development randomized controlled trial of this brief intervention for adolescents who are suicidal and psychiatrically hospitalized. The intervention, As Safe as Possible (ASAP), funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, was designed to augment protective factors against recurrent suicidal behavior. The intervention includes a telephone app (BRITE) that promotes emotion regulation and provides access to a personalized safety plan during transition from inpatient care to outpatient care.

Method

Participants

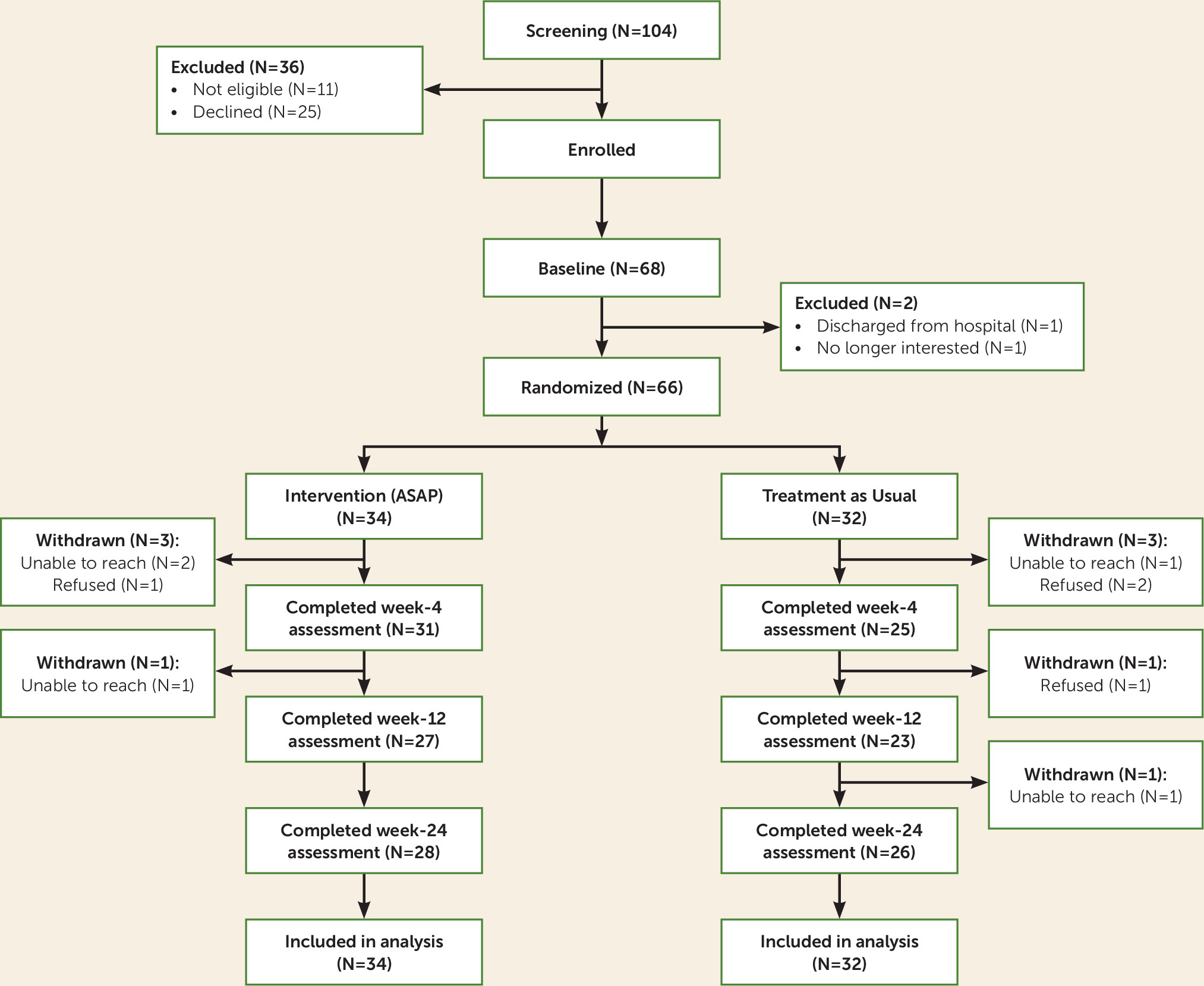

Participants were adolescents (12–18 years old) who presented to psychiatric inpatient units at two academic medical centers with recent suicidal ideation with a plan or intent or a recent suicide attempt. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at both sites, and written informed assent and consent were provided by the adolescents and their parents or guardians, respectively, upon admission. Exclusion criteria were need for residential treatment, active involvement of child protective services, mania, psychosis, autism, and intellectual disability. A total of 104 inpatients were evaluated for eligibility. Of these, 93 were deemed eligible, and 68 (73.1%) of those who were eligible consented to participate in the study (

Figure 1). Of the 68 inpatients who consented to participate, two were excluded after baseline (one was discharged before completing baseline measures, and one declined assessment), which resulted in 66 inpatients who were randomly assigned. Participants were in midadolescence (mean age=15.1 years [SD=1.5]) and largely female (89.4%) and Caucasian (77.3%). The median income bracket was 3.5 (interquartile range=4), corresponding to a median income range of $50,000–$74,999. Participants had moderate to severe depression (mean=18.4 [SD=5.3]), as measured by the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (

18), as well as significant suicidal ideation (mean=66.6 [SD=22.0]), as measured by the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–Junior High School Version (

19). Although 60% of participants were hospitalized for a recent suicide attempt, 80% had a lifetime history of attempt, as measured by the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (

20), and 40% were hospitalized because of suicidal ideation. The majority of participants had a clinical diagnosis of major depression (86.4%), often comorbid with an anxiety disorder (57.6%). Diagnoses were also obtained with the Youth Self-Report (

21), with similar results.

Study Design

Participants were randomly assigned to ASAP plus treatment as usual or to treatment as usual alone by using a Web-based computer program based on Efron’s biased coin toss (

22). Participants were balanced both within and across sites on sex, history of past suicide attempts, and drug or alcohol use. Positive drug or alcohol use was defined as an admitting diagnosis or a positive screen on the CRAFFT [Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, and Trouble] questionnaire (

23).

Treatment intervention (ASAP).

ASAP consisted of four modules—chain analysis and safety planning; distress tolerance and emotion regulation; increasing positive affect through savoring and switching; and review of the skills, safety plan, and app—and was delivered using a motivational interviewing framework on the inpatient unit (

Figure 2) (

24,

25). The intervention used in this study (including the app described below) was first piloted in two open trials with 17 participants and modified on the basis of clinician and participant feedback (

26).

The ASAP therapist contacted the participant by telephone at 1 and 2 weeks after hospital discharge to review the use of the safety plan, ASAP components, app use, and adherence to the recommended care.

Smartphone app: BRITE.

A smartphone app, compatible with the iOS and Android platforms and compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, provided each participant with convenient access to distress tolerance strategies, emotion regulation skills, and the safety plan, personalized to the preferences of the participant and populated by the therapist in collaboration with the participant (

26). Participants received daily text messages to rate their level of emotional distress (on a scale of 1–5, with 5 being “most upsetting”). On the basis of their level of distress, participants were offered a range of distress tolerance and emotion regulation skills, with the ability to upload support materials (videos, web sites, and photographs). For participants at the highest level of distress, the app presented the safety plan, including interpersonal support and clinical contact options. Screenshots from the app are shown in

Figure 3.

Treatment as usual.

Inpatient care across sites focused on diagnosis, safety assessment, stabilization, pharmacotherapy, psychoeducation, and disposition. Referrals for outpatient treatment were provided before discharge. Unit therapists developed a safety plan with the patient and the patient’s family, although no standard protocol was followed.

Treatment fidelity and quality assurance.

All therapists (N=5) had at least master’s-level training in psychology or counseling or were enrolled in a clinical psychology doctoral program. Therapists received training on the intervention, including training in motivational interviewing with expert co-investigators for the study (A.D., T.G.). All treatment sessions were audio-recorded. Weekly supervision telephone calls were held to review cases and monitor treatment quality. The major components of the treatment (motivational interviewing, chain analysis, distress tolerance, savoring, and safety planning) were quality rated for 20% of the ASAP sessions by study coauthors with expertise in each component. The quality rating for motivational interviewing was derived from the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (version 3.1.1) (

27). Quality ratings for chain analysis, distress tolerance, and savoring were derived from the Cognitive Therapy Scale (

28), and the quality of the safety planning was reviewed with the Safety Plan Rating Scale (for further details, see the

online supplement). Eighty percent or more of all sessions (N=29) were rated as adequate.

Assessments

Demographic information, intake diagnoses, and length of hospital stay were obtained from medical records. Assessments included dimensional measures of psychopathology (with the Youth Self-Report scale) (

21), anxiety (with the five-item Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders scale) (

29), depression (with the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire) (

18), and alcohol and drug use (with CRAFFT) (

22). Clinical treatment targets were reasons for living, assessed with the Reasons for Living Inventory for Adolescents (

30), emotion regulation, assessed with the Regulation of Emotions Questionnaire (

31), distress tolerance, assessed with the Distress Tolerance Scale (

32), and social support, assessed with the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (

33).

Assessments were conducted at baseline and weeks 4, 12, and 24 by independent evaluators blind to study condition. Independent evaluators were supervised by trained and experienced evaluators. Independent ratings of audiotaped evaluations on the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (

20) showed excellent interrater reliability (kappa values ranged from 0.63 [SE=0.27] to 0.83 [SE=0.28]).

Outcome Measures

Suicidal ideation and behavior.

The primary and secondary outcomes were time to suicide attempt and severity of suicidal ideation, respectively. Past and current suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury were assessed with the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale, and current suicidal ideation was assessed with the self-reported Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–Junior High School Version (

19,

20). Time to attempt was calculated from the initiation of the intervention.

Treatment utilization.

Treatment history was obtained using week-by-week ratings on items derived from the Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (

34).

Self-reported client satisfaction.

Satisfaction ratings with the app and with the ASAP intervention were obtained from participants and parents by using an adaptation of the Post-Study Satisfaction and Usability Questionnaire (

35) and the eight-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (

36), respectively.

Data Analysis

We aimed to recruit 80 participants, 40 in each cell, with an alpha of 0.05 (two-sided), anticipating a power of 0.80 (1– beta) to detect an effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.63. With a recruited sample of 66 participants and 60 participants retained for follow-up (ASAP plus treatment as usual group, N=31; treatment as usual group, N=29), we were able to detect an effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.74 and a hazard ratio of 0.48 or less for survival models.

We conducted our primary analyses with all 66 inpatients enrolled. We followed the analytic plan of our protocol by first comparing the participants’ baseline characteristics by group, by site, and by patients retained compared with patients not retained by using standard univariate statistics. We compared the rates of suicidal behavior by intervention group over the 24-week follow-up with chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests and the time to suicide attempt with Kaplan-Meier curves. We identified variables associated with time to attempt and controlled for these variables, along with age, sex, income, and site, by using Cox proportional hazards models. As per our protocol, we tested for moderation on all stratification variables (age, sex, drug or alcohol abuse, past history of suicide attempt), along with site. Mixed-effects regression with group, time (weeks since baseline), and group-by-time interaction was used to examine the effects of treatment on the course of suicidal ideation over time, and moderation was tested on all stratification variables. The effect of the intervention on the four putative targets (reasons for living, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and social support) was assessed with mixed-effects linear regression. Effect sizes were calculated as Hedges’ g (

37). All analyses were intent-to-treat, significance level was set at an alpha of 0.05, and analyses were conducted with Stata, version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.).

Results

Of the 66 randomly assigned participants, 34 were randomly assigned to ASAP intervention plus treatment as usual, and 32 were randomly assigned to treatment as usual alone. Because the timing of our assessments was from baseline rather than from hospital discharge, three participants completed the week 4 assessments while still in the hospital, and one of the week 12 assessments was conducted for a participant during a readmission hospitalization. Six participants (9.1%, three in each treatment group) did not complete any follow-up assessments. There were no site differences between the two groups in loss to follow-up (3.5% compared with 13.5%, Fisher’s exact test, p=0.22). Participants who were lost to follow-up, compared with participants who were retained for at least one assessment, had higher baseline suicidal ideation (mean=78.3 [SD=7.2] compared with mean=65.5 [SD=22.7], t=3.11, p=0.01) and higher levels of self-reported anxiety (mean=56.8 [SD=4.9] compared with mean=47.6 [SD=16.0], t=3.23, p=0.004).

Baseline Characteristics

Comparisons between the two groups at baseline are summarized in Table S1 in the

online data supplement. The ASAP plus treatment as usual group demonstrated greater sleep disturbance on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (

38) (ASAP plus treatment as usual group: mean=12.4 [SD=3.7]; treatment as usual group: mean=10.1 [SD=3.6]; t=2.47, p=0.02).

Site differences included age (mean=15.7 years [SD=1.1] compared with mean=14.6 years [SD=1.7], t=3.04, p=0.004), annual income bracket (mean=3.0 [SD=1.5] compared with mean=3.9 [SD=1.3], z=−2.31, p=0.02), living with both biological parents (N=5 [17.2%] compared with N=19 [52.8%], χ2=8.71, df=1, p=0.003), lifetime suicidal ideation with plan and intent (N=29 [100.0%] compared with N=30 [83.3%], χ2=5.32, df=1, p=0.03), and number of weeks hospitalized (mean=3.5 [SD=2.8] compared with mean=1.1 [SD=0.2], z=6.53, p<0.001).

ASAP Intervention and Bridging Calls

The median total duration of the inpatient intervention was 2.7 hours (interquartile range=2.8 hours), delivered over a median of three sessions (interquartile range=1), averaging 53 minutes per session. Two participants (5.9%) had two sessions, 18 (52.9%) had three, 12 (35.3%) had four, and two (5.9%) had five.

Of the 34 participants who received ASAP plus treatment as usual, 10 had family sessions, with a median duration of 23 minutes (interquartile range=15 minutes). After hospital discharge, 26 of the 34 participants received at least one bridging telephone call (median=1.5, interquartile range=2), with a median total duration of 17.5 minutes (interquartile range=35).

Follow-Up Assessments

Suicidal behavior.

There were no significant differences in the rates of suicide attempts after hospital discharge, although the results were in the hypothesized direction (ASAP plus treatment as usual group: N=5 [16.1%]; treatment as usual group: N=9 [31%]; χ

2=1.86, df=1, p=0.17, g=−0.36) (

Table 1), as were the results for time to attempt between the two groups (Wilcoxon: χ

2=0.76, df=1, p=0.38; log-rank: χ

2=1.74, df=1, p=0.19; hazard ratio=0.49, 95% CI=0.16, 1.47, z=–1.27, p=0.20).

Past history of a suicide attempt moderated treatment outcome (hazard ratio=0.07, 95% CI=0.01, 0.79, z=−2.15, p=0.03), with a stronger, albeit nonsignificant, effect of ASAP plus treatment as usual among patients with a history of suicide attempt (hazard ratio=0.23, 95% CI=0.05, 1.09, z=−1.85, p=0.06).

Because our intent for the intervention was to reduce suicide attempts following hospital discharge, we reanalyzed the data excluding three participants who were still in the hospital at the time of suicide attempt. The difference in the rates of suicide attempts between the two groups was not significant but was in the hypothesized direction (10.3% [N=3] compared with 28.6% [N=8]; χ2=3.04, df=1, p=0.08, g=−0.47), as was the difference in time to treatment (Wilcoxon: χ2=1.66, df=1, p=0.20; log-rank: χ2=3.02, df=1, p=0.08; hazard ratio=0.33, 95% CI=0.09, 1.26, z=–1.62, p=0.11). After we adjusted for significant covariates related to time to suicide attempt (age), the ASAP plus treatment as usual group had a longer time to suicide attempt (hazard ratio=0.19, 95% CI=0.04, 0.85, z=−2.18, p=0.03).

Mixed-effects regression showed an effect of time on suicidal ideation for the entire sample (β=–0.57, 95% CI=–0.84, –0.30, z=−4.09, p<0.001) but not for group or group-by-time interaction, indicating a similar decrease in suicidal ideation over time between the two groups.

Mixed-effects regression indicated an increase in social support over time in the ASAP plus treatment as usual group compared with the treatment as usual group (group-by-time interaction: β=0.32, 95% CI=0.08, 0.56, z=2.60, p=0.01). No other treatment targets showed an effect for group over time.

In the ASAP plus treatment as usual group, participants whose families attended one or more treatment sessions had lower ideation over time (treatment-by-time interaction: β=–0.61, 95% CI=–1.12, –0.11, z=−2.38, p=0.02), although there was no effect on time to attempt.

Smartphone app.

Most participants in the ASAP plus treatment as usual group (70.6%) used the app at least once (

Table 2). Participants in this group rated their mood a median of 19 times (interquartile range=54), and 75.0% added content (number of times content was added: median=10, interquartile range=17), while 41.7% removed content (number of times content was removed: median=8.5, interquartile range=1). Nearly one-half (45.5%) of participants activated their contacts at least once as part of their safety plan. The median number of times participants accessed their contacts was 21 (interquartile range=34). We did not find a relationship between the frequency of app use and the risk for suicide attempt (hazard ratio=1.01, 95% CI=0.98, 1.04, z=0.54, p=0.59) or decline in suicidal ideation (Spearman’s ρ=–0.24, p=0.23), although the relationship between the frequency of mood ratings and increase in reasons for living was in the hypothesized direction (Spearman’s ρ=0.37, p=0.08).

Participant satisfaction.

The scores on the app from the Computer Systems Usability Questionnaire (

40) indicated a generally high level of satisfaction (lower scores indicate greater satisfaction; range, 10–70) for week 4 (mean=17.6 [SD=7.1]), week 12 (mean=18.6 [SD=10.4]), and week 24 (mean=18.4 [SD=8.0]).

There was no difference in client satisfaction at the end of the intervention, as measured with the Computer Systems Usability Questionnaire (

39), although results were in the hypothesized direction (ASAP plus treatment as usual group: mean=26.6 [SD=3.8]; treatment as usual group: mean=24.1 [SD=5.2]; z=1.64, p=0.10, g=0.58).

Service use and medications.

There were no differences between the two groups in the duration of hospital stays for the index episode (ASAP plus treatment as usual group: mean=2.1 weeks [SD=2.3]; treatment as usual group: mean=2.3 weeks [SD=2.3]; z=−0.71, p=0.48). Nearly all participants engaged in some type of treatment after discharge from the hospital (ASAP plus treatment as usual group: 96.7% [N=29]; treatment as usual group: 96.6% [N=28]). Unexpectedly, patients in the ASAP plus treatment as usual group were less likely than patients in the treatment as usual group to participate in outpatient therapy (60.0% [N=18] compared with 89.7% [N=26]; χ2=6.84, df=1, p=0.01, g=–0.73). However, they had higher, albeit nonsignificant, rates of use of more intensive interventions (e.g., intensive outpatient treatment, partial hospitalization, and residential treatment) (ASAP plus treatment as usual group: 73.1% [N=19]; treatment as usual group: 53.6% [N=15]; χ2=2.20, df=1, p=0.14, g=0.41). The two groups showed similar rates of emergency department visits (ASAP plus treatment as usual group: 13.3% [N=4]; treatment as usual group: 10.3% [N=3]; Fisher’s exact test, p>0.99, g=0.09). Stratified contrasts showed similar results between the two groups with regard to the rates of and time to suicide attempt among participants in more intensive programs (ASAP plus treatment as usual group: 10.5%; treatment as usual group: 26.7%; hazard ratio=0.42, 95% CI=0.08, 2.37, z=−0.98, p=0.33), as well as among participants in outpatient programs (ASAP plus treatment as usual group: 14.3%; treatment as usual group: 38.5%; hazard ratio=0.23, 95% CI=0.03, 2.02, z=−1.33, p=0.18).

Participants who had follow-up assessments were evaluated on medication use after hospital discharge. Participants assigned to ASAP plus treatment as usual were more likely to use a pharmacological sleep aid (ASAP plus treatment as usual group: N=19 [63.3%]; treatment as usual group: N=10 [34.5%]; χ2=4.91, df=1, p=0.03), whereas participants in the treatment as usual group were more likely to receive antipsychotic medication (treatment as usual group: N=12 [41.4%]; ASAP plus treatment as usual group: N=4 [13.3%]; χ2=5.87, df=1, p=0.02). Adjusting for differences in medication use did not alter our initial findings (see Tables S2–S4 in the online supplement).

Discussion

In this treatment development study, we demonstrated the acceptability and feasibility of the ASAP intervention program and the supporting BRITE app. Although this randomized controlled trial was not large enough to detect even substantial clinical effects, the rate of suicide attempt among participants assigned to ASAP plus treatment as usual was half that of participants in the treatment as usual alone group, indicating that this intervention is promising and may have utility in the reduction of postdischarge suicide attempts among hospitalized, suicidal adolescents.

To our knowledge, this is the first inpatient intervention designed to reduce suicide attempts following hospital discharge, with the exception of one study conducted nearly two decades ago in which caring letters were sent after discharge to adults at high risk for suicide who refused further outpatient care (

40). ASAP is brief, focused, and supported by an app, and its strongest effects were shown in the most vulnerable subsample here, namely, participants who had made a previous suicide attempt. Supporting the likelihood that this intervention has the potential to be widely disseminated, the ASAP program was well accepted, and a high proportion of eligible participants were recruited into the study. However, the sample size was small, with limited power, and largely female and Caucasian, which limits our ability to generalize to other populations. We did not use structured diagnostic assessments but instead relied on clinical diagnoses and a self-report diagnostic tool. Another limitation was the difficulty engaging families in the intervention during hospitalization. Finally, our design did not allow us to determine which components of the intervention or app were effective.

As hypothesized, participants assigned to ASAP plus treatment as usual tended to have a lower hazard of suicide attempts after hospital discharge, with significant moderation among persons with a history of a suicide attempt. Sensitivity analyses excluding three participants who made suicide attempts while still hospitalized continued to be in the hypothesized direction. Although a larger sample will be required in order to definitively assert that ASAP is effective, these findings are plausible because the focus of the intervention was on well-recognized intervention targets for suicidal behavior (reasons for living, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and social support).

There were no main effects for the intervention on suicidal ideation, which is consistent with our primary focus on reducing the risk of acting on suicidal urges. Participants in the ASAP plus treatment as usual group showed a higher level of social support over time compared with participants in the treatment as usual condition. Thus, the ASAP intervention appeared to affect social support, which may be related to the lower rate of suicide attempts in this treatment group.

The majority of participants in the ASAP plus treatment as usual group used the app actively, modified content, frequently rated their level of distress, activated the personal contacts on their safety plan, and reported high satisfaction with the app. Further study is needed to determine whether the app adds to the ASAP intervention, and if so, which components are the most important in protecting youths from suicidal behavior.

Although both treatment groups showed very high rates of participation in treatment after hospital discharge, the ASAP plus treatment as usual group was statistically less likely to be involved in outpatient care and, while not statistically significant, had higher rates of involvement in higher-intensity treatments. However, the effect of ASAP plus treatment as usual compared with treatment as usual alone on subsequent suicide attempts was similar among participants who were in higher levels of care and participants who were in outpatient treatment.

The low rate of family engagement in the ASAP intervention speaks to the rapid pace of inpatient care, during which parents may not have had the time or inclination to participate in research above and beyond visitation and inpatient therapeutic activities. It is noteworthy that participants whose family members received at least one ASAP session had a greater decline in suicidal ideation over time than participants who did not receive the intervention (even after adjusting for baseline differences). Because future studies of ASAP on inpatient units will most likely be delivered by inpatient staff, they may be in a better position to promote and improve family engagement.

In summary, these findings indicate that ASAP and the BRITE smartphone app are acceptable, feasible, and promising interventions for hospitalized, suicidal adolescents. Further study is needed to determine which aspects of ASAP and the BRITE app are most active, and hence worth disseminating, and whether the intervention can be effectively delivered on inpatient units by existing staff.

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank the children and families who participated in this study.