Personalized medicine holds great promise in improving the quality of treatments for mental health conditions (

1), whereas the concept of stepped care has the potential to make these interventions more available and cost efficient (

2). With personalized care, treatment outcomes are improved by giving individual patients a treatment that is precisely right for them (

3). In stepped care, on the other hand, all or most patients are given the same, least intensive, most readily available treatment. Those who require additional treatment are then moved up a step to intensified treatment. Personalized medicine is usually thought of as a way to match patients to the optimal intervention before initiating treatment (

3,

4) because no intervention is likely to be ideal for all. If successful, personalized medicine would overcome a shortcoming of stepped care, where many patients have to go through a number of steps before reaching a treatment that is effective for them and consequently be exposed to treatment failure. In fact, a large evaluation of the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies project, an implemented stepped-care system, showed that moving up through steps was the strongest predictor of recovery (

5). This may indicate that low-level steps are inappropriate starting points for many patients. Starting, and working through, ineffective treatments may result in prolonged suffering and potentially unnecessary costs.

However, the concept of personalized care need not be restricted to patient-treatment matching before treatment initiation; it could also include adjusting treatment on the basis of cues of treatment nonresponse. For instance, adjusting the dosage of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor based on detection of cytochrome genetic polymorphism or switching to another compound could be framed as ways to personalize treatment. In relation to psychological treatment, studies have shown that clinical data collected during treatment are more reliable in predicting outcome than baseline data (

7,

8). Lambert and colleagues have repeatedly shown that progress monitoring, based on structured patient self-report and feedback tools for therapists, improves outcomes, especially for patients who are predicted not to respond to a treatment, or to deteriorate (

9). Beyond providing the therapist with a prediction, a plan for how the therapist should act on the prediction is thought to improve the effect further (

9), but this has never been tested experimentally.

In this study, we aimed to demonstrate a proof of concept and develop and test an adaptive treatment strategy by using baseline data and data from the first few treatment weeks to predict final outcome, by presenting this prediction to the therapist in a comprehensible way, and, in cases where an unsuccessful outcome is predicted, by providing a method to intensify and personalize the ongoing treatment to adapt it to the needs of the patient. If successful, this could help transform stepped care into more of an accelerated care, where entry-level treatments can be adaptive, thus avoiding the need to wait for an initial treatment attempt to fail before intensifying care.

To increase the probability of a successful demonstration, we made two choices. First, the context of therapist-supported, Internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy (ICBT) was chosen because it is empirically supported, allows for easily collected data, and presents several possible adaptations regarding intensity and delivery (

10). This treatment format has also been implicated as a key first-step intervention in stepped-care models (

11–

13). Second, we chose ICBT for patients with insomnia because it is a well-delimited clinical area with well-defined therapeutic techniques facilitating the assessment of problems related to progress and adherence, while also having strong evidence (

14,

15) but room for overall improvement (

16).

Results

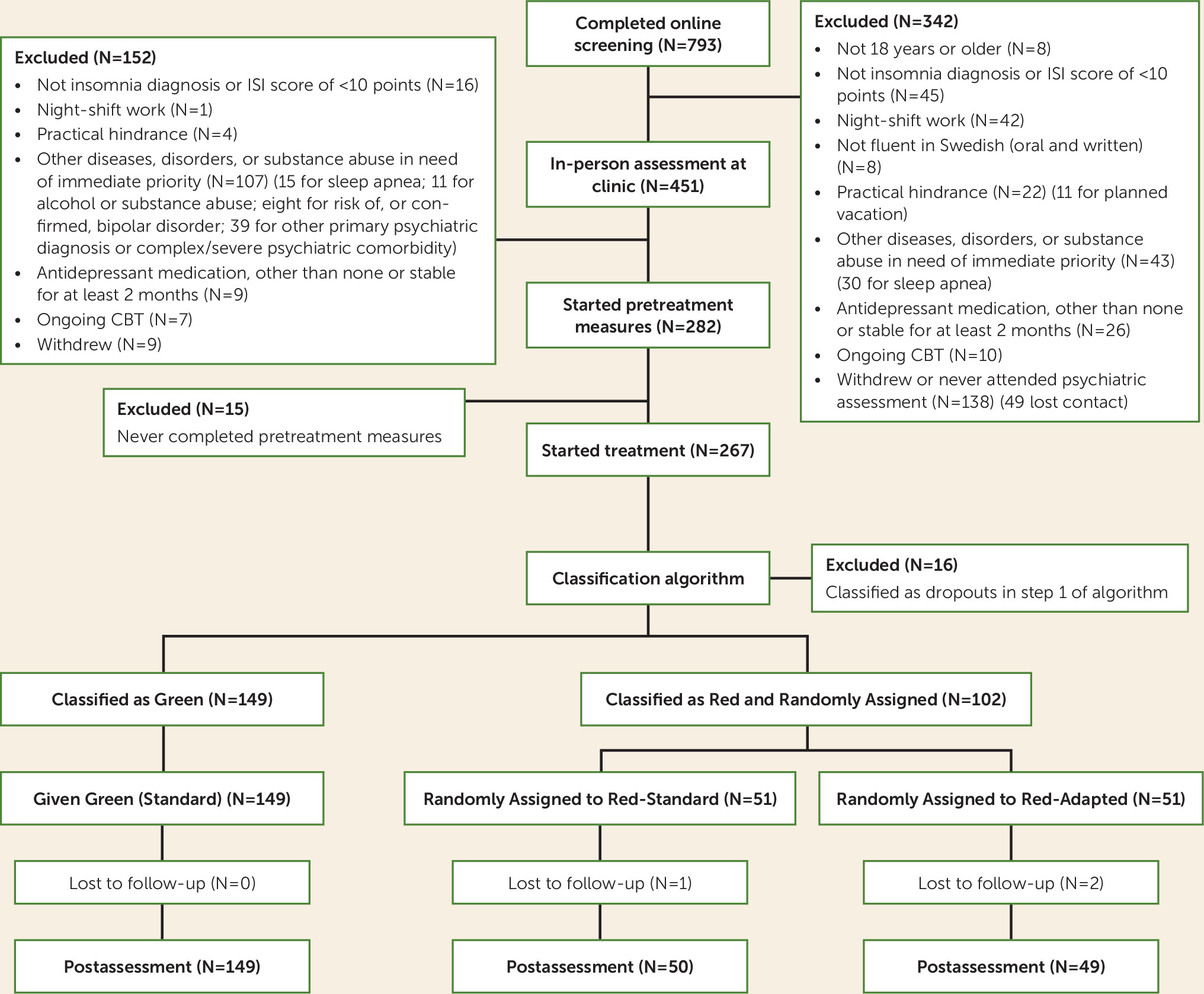

A total of 251 patients were included and subjected to the classification procedure, in which 149 were classified as Green and 102 as Red.

Missing Data

Three of the six missing online posttreatment Insomnia Severity Index scores could be replaced with interview versions of the Insomnia Severity Index, in accordance with Hedman et al. (

26).

Of 10 measurement points, 71% of participants provided data for all 10 points, and 91% provided data for eight or more points. Attrition at posttreatment assessment was low, at 1.2%. No participant provided fewer than two data points, and therefore all participants are included in the estimation of all coefficients in the primary outcome analyses (

25).

Missing data analysis for nonignorable missing data revealed no variables with significant correlations to both outcome and to being absent.

Patient Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the different classified and randomized groups are summarized in

Table 1. Having completed postsecondary education was significantly less common in the Red-Standard group compared with the Red-Adapted group (χ

2=5.67, df=1, p=0.017). As a sensitivity analysis, the two linear mixed-model analyses were repeated with postsecondary education as a covariate, which did not change the results.

Primary Outcomes

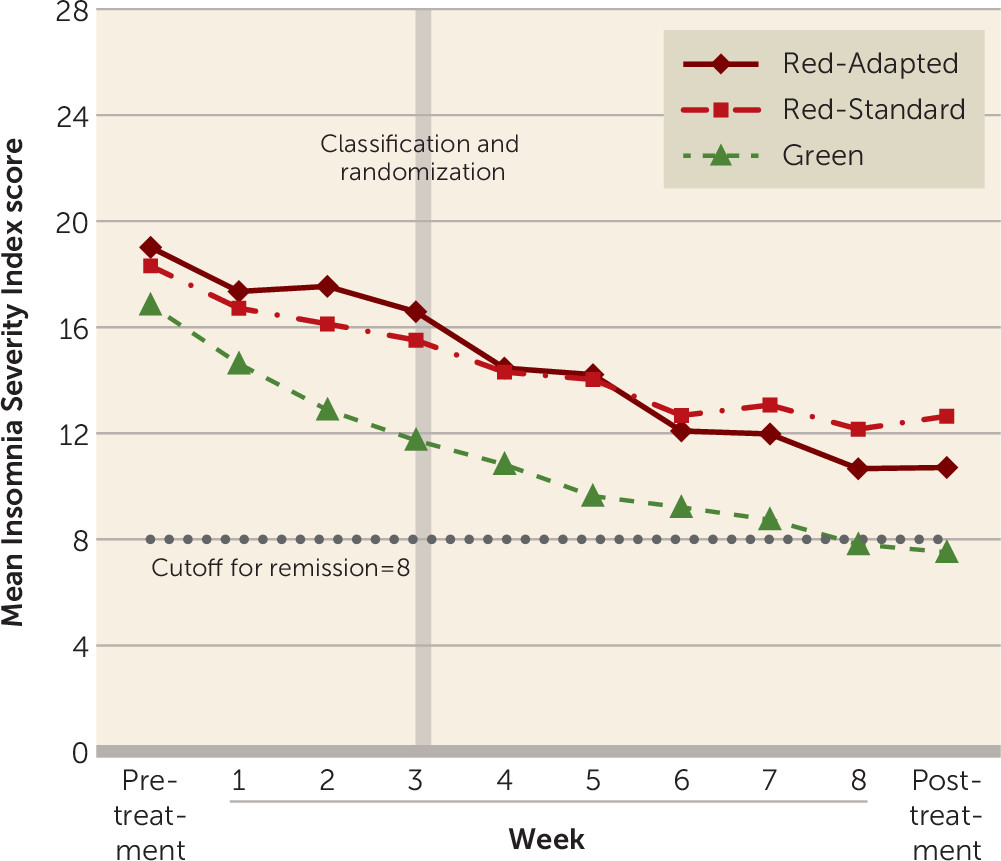

The means and standard deviations of scores on the Insomnia Severity Index across groups are presented in

Table 2, and score trajectories across all measurement points are shown in

Figure 2. There were significant main effects of time for both models (p<0.001), indicating that all three groups improved from pretreatment to posttreatment assessments. There was also a significant effect of group at the intercept (p<0.001), indicating that patients in the Red group had higher pretreatment scores on average than those in the Green group.

Hypothesis 1: treatment failure can be predicted.

There was a significant group-by-time interaction indicating larger reductions over time in symptom ratings for the Green group compared with the Red-Standard group (p<0.001), supporting our first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: treatment adaptation is beneficial.

Before classification, both Red groups had significantly worse treatment effects compared with the Green group (p<0.001 for both Red groups) but were not significantly different from each other (p=0.775). After classification, the Red-Adapted group improved significantly more (p<0.001) than the Red-Standard group and significantly more than the Green group (p<0.001). This result indicates that the rate of improvement accelerated when treatment was adapted, in support of our second hypothesis. After classification, Green and Red-Standard patients did not differ significantly in change over time (p=0.214).

Treatment Failure, Response, Remission, and Deterioration

Categorical outcomes are summarized in

Table 3. Treatment failure was significantly more common among patients in the Red-Standard group than those in the Green and Red-Adapted groups, who did not differ significantly from each other. Remission was significantly more common in the Green group than the other groups and was not statistically different between Red groups. Responder status and reductions ≥50% in symptom ratings were not significantly different between the Green and Red-Adapted groups, and patients in the Red-Adapted group had significantly higher response rates and ≥50% reductions in symptom ratings compared with those in the Red-Standard group. Deterioration was too rare in all groups to produce meaningful statistical comparisons.

Therapist Adherence to the Adaptive Treatment Strategy

Therapist adherence was good. Therapists spent, on average, 110.9 minutes per patient writing messages and talking on the telephone with patients in standard treatment overall, compared with 179.6 minutes per patient in adapted treatment (t=7.7, df=249, p<0.001); this equates to a little more than 1 extra hour per treatment, or about 14 extra minutes per week, for the remaining 5 weeks of treatment. The same pattern was observed in the number of message or telephone contacts (17.3 in standard treatment compared with 19.8 in adapted treatment; t=3.4, df=249, p=0.001). When comparing the Green with the Red-Standard group, the total time spent by therapists was lower for the Red-Standard group (24.3 minutes less in total, or 2.7 minutes less per week; t=3.1, df=198, p=0.003). However, that difference disappears when looking at time spent per module (t=1.1, df=198, p=0.269) because the Red-Standard group completed fewer modules (t=8.6, df=198, p<0.001) and therefore elicited fewer responses and less feedback from therapists. There was no significant effect of therapist licensure on change in scores on the Insomnia Severity Index or in any of the categorical outcomes. As a sensitivity analysis, the two linear mixed-model analyses were repeated with assignment to a licensed therapist or not as a covariate, and the results did not change.

Medication Changes and Use of Other Treatments

More patients in the Green group than in the Red groups stopped taking sleep medication (Green group compared with Red-Adapted group, χ2=6.76, df=2, p=0.03; Green group compared with Red-Standard group, χ2=11.45, df=2, p=0.003). Eight patients in the Red-Adapted group (16%) and six in the Red-Standard group (12%) had stopped taking sleep medication at the posttreatment assessment, which was not a statistically significant difference (χ2=0.619, df=2, p=0.73). There were no statistically significant differences between groups in terms of starting sleep medication or increasing or decreasing its dosage. A significantly greater number of patients in the Red-Standard group reported having started some other intervention (CBT, medication, or other) to reduce sleep problems during the study period, compared with patients in the Red-Adapted and Green groups: six (13.3%), two (4.1%), and five (3.4%), respectively (Fisher’s exact p=0.039).

Treatment Satisfaction and Adverse Events

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire scores were good to excellent (

22) in all three groups (Red-Standard, mean=24.1, SD=4.1; Red-Adapted, mean=24.7, SD=4.8; Green, mean=27.1, SD=4.1) but were significantly higher among patients in the Green group compared with the other two groups (F=11.63, df=2, 24, p<0.001).

No serious adverse events were reported. Reporting of any adverse event or negative effect in response to an open-ended question at the posttreatment assessment was not significantly different between any groups, although it was slightly less common among patients in the Red-Adapted group (24%) than among those in the Red-Standard (31%) or Green (30%) groups. The most common adverse events were sleep getting worse in conjunction with starting sleep restriction (41% of adverse events, or 12% of the full sample) and an increase in physical symptoms (23% of adverse events, or 7% of the full sample), most commonly a subjective experience of increased susceptibility to getting a cold or the flu while feeling sleep deprived.

Discussion

Our aim in this study was to investigate the usefulness of an adaptive treatment strategy using an individual outcome prediction algorithm and adapting treatment for patients at risk of treatment failure. As hypothesized, patients classified as at risk of experiencing treatment failure who did not receive adapted treatment (Red-Standard) had significantly less symptom reduction than patients identified as probable successes (Green). Furthermore, patients classified as at risk of experiencing treatment failure who received the adapted treatment (Red-Adapted) had significantly greater symptom reduction than at-risk patients who received standard treatment (Red-Standard).

Although at-risk patients who received adapted treatment improved more than those who received standard treatment, they did not do quite as well as the patients who were not at risk. This could be because at-risk patients had markedly higher pretreatment symptom levels, but it could also indicate that some at-risk patients are not adequately helped by this type of adaptation to treatment. However, once adapted treatment was given, at-risk patients showed a steeper decrease in symptom rating than not-at-risk patients, so they might have caught up if treatment had been extended. Importantly, the adapted treatment offered in this trial does not seem to be very time consuming. Therapists spent, on average, only about 14 more minutes per remaining week on these patients, and that time includes the 30-minute adaptation assessment. In addition, the adaptations were limited to format and intensity only, and no novel interventions were added.

Our findings are in line with those of Lambert (

9) in that structured monitoring and identification of patients who are not progressing well, coupled with active intervention from therapists, can improve outcomes in psychotherapy in general. In the present trial, the treatment adaptations and therapists’ behaviors were uniquely monitored and restricted to certain types of adaptation only, providing important evidence of the utility of relatively simple adaptations.

One key difference is in the rates of deterioration. Hannan et al. (

27) observed about 7% of patients leaving treatment as deteriorated, and Shimokawa et al. (

28) found 20% deterioration without support tools, which was reduced to 11% with support tools. In our study, 1.2% of patients deteriorated without adapted treatment and 0% did so with adaptation. However, deterioration rates in ICBT could be lower than in psychotherapy in general (

29), and insomnia is often chronic and stable, possibly making patients unlikely to deteriorate.

The number of reported adverse events is higher than what is usually reported in psychotherapy research. However, adverse events have most often not been explicitly measured and reported in previous research, as noted by Rozental et al. (

30), suggesting an underestimation in previous findings. Also, regarding CBT for insomnia, the number of reported adverse events in this study does in fact match previous findings relatively well (e.g.,

31,

32). The intervention itself (sleep restriction) is associated with a number of specific, acute side effects that are distressing but at the same time passing and expected, or even considered hypothetical mechanisms (

31,

32).

Important strengths of this trial are the random assignment to adapted treatment for at-risk patients and the patients’ blind to both assignment and classification, especially because the primary outcome is patient rated. Moreover, there was very little attrition and missing data.

One limitation is that therapists were aware that at-risk patients were predicted to experience treatment failure, which could affect therapist performance (causing them to give up or to put in extra effort). However, this effect is less likely in the context of this study’s Internet-delivered treatment, where much of the treatment is standardized and therapists were supervised in terms of time spent and what to do with patients in standard treatment (i.e., not to undertreat them).

Another limitation is that time spent mailing materials to patients in the adapted treatment group or trying, but failing, to reach someone on the telephone was not measured. At-risk patients in standard care received less time overall probably because they were inactive, illustrated by the fact that time spent per message did not differ. Overall, our data indicate that the therapists followed the adaptive treatment strategy protocol for all groups.

The use of ICBT for insomnia reduces the generalizability of these findings, as it is possible that other treatment formats or other target conditions would respond differently to the adapted treatment. On the other hand, the standardized ICBT made the comparison less prone to confounding by other factors.

The individual outcome prediction tool was not validated beforehand, but instead validation and trial of the adapted treatment were parallel. Had the algorithm been evaluated beforehand, it might have been more accurate and thus produced clearer results. Although the results of this trial are already quite clear, further studies are still needed to tune and automate such algorithms to maximize their utility.

Another limitation is the lack of follow-up data. Further studies are needed to determine the long-term effects of the adapted treatment and the progression of at-risk patients who do not receive adapted treatment over time. The aim of the present study, however, was to investigate immediate effects of using an adaptive treatment strategy.

Future studies should address how the proposed model works in regular care, where it may be difficult to provide adapted treatment only to at-risk patients or to address only one condition. However, focusing on only one condition or problem may be beneficial in itself, at least in insomnia, as evidence suggests that providing a focused insomnia intervention can be beneficial even for patients with comorbidities (

33,

34). In a broader health care delivery context, interventions utilizing adaptive treatment strategies could, together with the prospective matching of patients to treatments, transform the stepped-care paradigm into accelerated care, in order to shorten the time of suffering by minimizing time spent in low-intensity but nonhelpful interventions. In psychotherapy, where patient-treatment matching is still highly elusive, adaptive treatment strategies may be easier to create and implement in a useful way. For most patients, it may be more useful and accurate to determine early on that a treatment is not working, rather than trying to predict treatment failure before the treatment starts. In some implemented stepped-care systems today, it is possible that patients are already being moved to the next step before an ongoing treatment course is formally over if nonresponse or deterioration is noticed, or when a patient drops out. To our knowledge, however, moving a patient to the next step has so far never been done on the basis of empirical findings from randomized controlled trials or validated prediction algorithms.

In conclusion, our results suggest that an adaptive treatment strategy can be a feasible way to deliver psychiatric care and that it can increase treatment effects for at-risk patients and reduce the number of failed treatments. The classification algorithm and the adaptation of the treatment should be further developed, but this proof-of-concept study indicates that adaptive treatment strategies could be an important step in moving from stepped care into accelerated care.