Epidemiological and preclinical studies have identified maternal viral infection during pregnancy as a putative risk factor for schizophrenia (

1). However, there is a relative paucity of research on bacterial infection (

2–

4). Bacterial infections—such as urinary tract infection and bacterial vaginosis—are highly prevalent as a result of physiological changes and immune suppression during pregnancy (

5). Often asymptomatic, bacterial infections are largely overlooked and left untreated in antenatal care settings. However, such infections can pose a significant threat to pregnancy and healthy fetal development (

6,

7), and untreated infections have been associated with severe neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring (

8,

9).

Despite considerable evidence on the immediate impact of gestational bacterial infection on perinatal health, long-term neuropsychiatric consequences remain unclear. There have been only two previous prospective cohort studies that specifically investigated bacterial infection in relation to offspring risk for psychotic disorders. One study reported that maternal sinusitis, tonsillitis, pneumonia, cystitis, pyelonephritis, or bacterial venereal infection was associated with more than a twofold increase in schizophrenia risk (

2). This finding was replicated in another study specific to pyelonephritis (

10). We previously reported that maternal immune dysregulation in general was associated with a significantly higher risk of offspring psychotic disorders (

11,

12), although this was not specifically tied to bacterial infection.

Animal studies have provided robust experimental evidence on how maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy may cause lasting changes in the structure and function of the fetal brain (

13,

14). For example, murine embryos exposed to bacterial peptidoglycan (a key component of the bacterial cell wall) exhibited abnormal proliferation of neuronal precursor cells, permanently altering their brain architecture (

15). After birth, exposed offspring displayed behavioral, neurochemical, and neurophysiological abnormalities consistent with observations in people with psychotic illness (

15). Taken together, these experimental studies provide a strong rationale for testing the hypothesis that maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy disrupts fetal neurodevelopment, consistent with subsequent risk for psychotic disorders, using epidemiological samples. Thus, we hypothesized that maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy increases offspring risk of psychotic disorders in adulthood, and that the magnitude of this association varies as a function of severity of infectious exposure.

Earlier studies, including by our group, reported associations between gestational immune disruption and heightened risk of psychotic disorders among males to a greater extent than females (

12,

16–

18). To replicate these findings, we hypothesized that the effect of maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy on the risk of psychotic disorders would be greater among male than female offspring. In addition to sex differences, numerous studies have reported on strong heritability of psychotic illnesses (

19), with a substantial overlap with other psychiatric disorders (

20). In fact, previous studies have demonstrated the utility of family history as a proxy for genetic liability (

19,

21), and one study specifically investigated synergistic effects of familial liability to psychosis and prenatal bacterial infection on subsequent risk for schizophrenia (

10). These findings were substantiated by a more recent study finding that the impact of parental history of mental disorder was not confined to concordant parental mental disorders but rather that offspring are at increased risk of a wide range of mental disorders (

20). Given these findings taken together, we hypothesized that the association between maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy and psychosis risk would be greater among offspring with a parental history of mental illness than among those without.

Methods

Study Population

There were 16,188 live births enrolled between 1959 and 1966 at the Boston and Providence sites of the Collaborative Perinatal Project (CPP), currently known as the New England Family Study (NEFS). The CPP was initiated to investigate prospectively the prenatal and familial antecedents of pediatric, neurological, and psychological disorders of childhood (

22). Details of the CPP and NEFS methodology have been reported elsewhere (

11,

23–

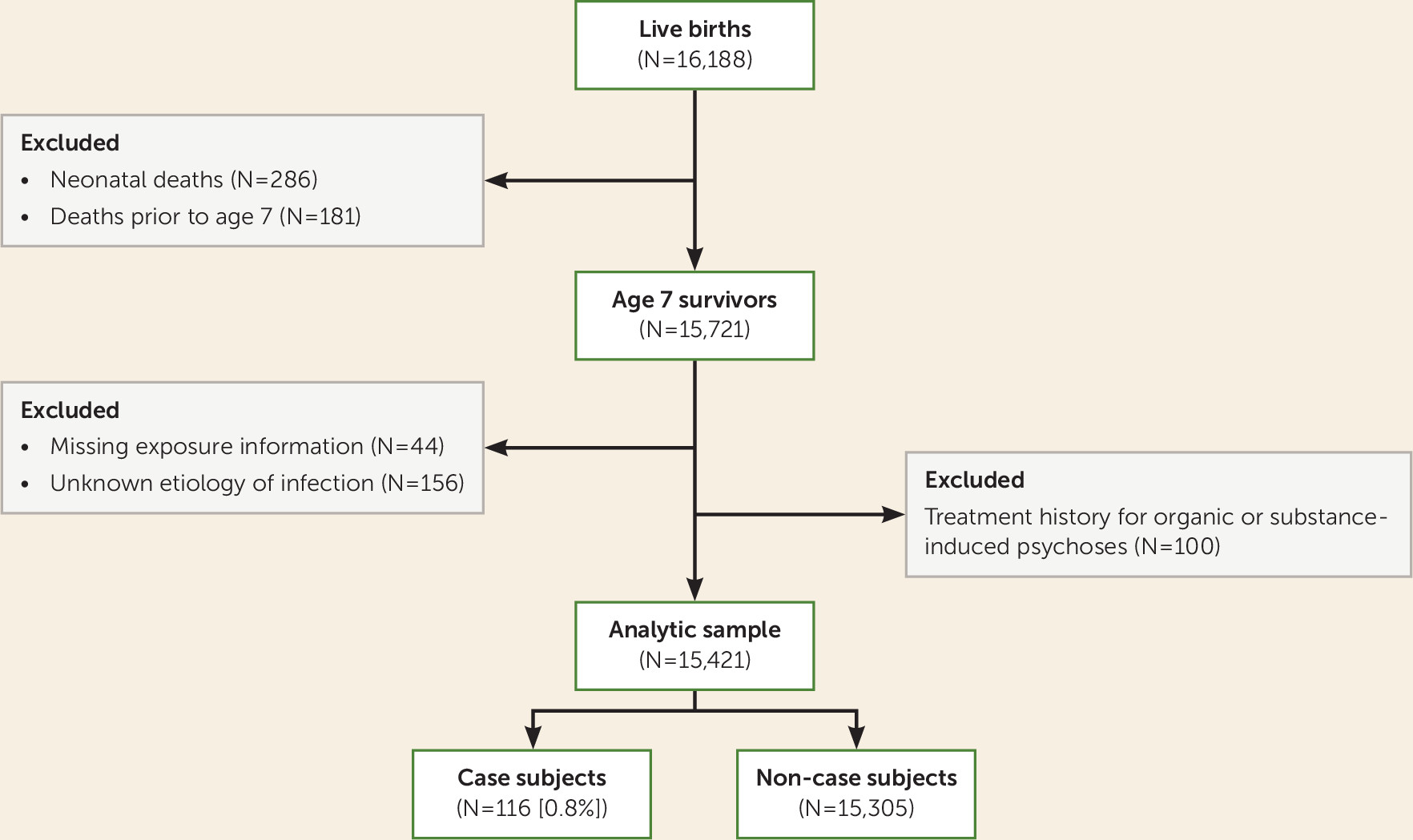

26). As shown in

Figure 1, we excluded offspring who did not survive to the period of risk for psychosis (N=467), those who had entirely missing records for infectious disease during their mothers’ pregnancy (N=44), and those whose mothers had infection of unknown etiology during pregnancy (N=156). In a series of previous follow-up studies of the NEFS participants, we identified those with psychotic disorders among the original parents and among the offspring, who are now adults in their 50s (

11,

23–

26). To minimize false positive cases of psychotic disorders in offspring, we further excluded those who had a treatment history for organic or substance-induced psychosis (N=100). The final analytic sample included a total of 15,421 participants.

Collection and Processing of the Exposure Data

Collection of the exposure data was jointly conducted by trained nonphysician interviewers and physicians, beginning at the time of registration for prenatal care, at intervals of 4 weeks during the first 7 months of pregnancy, every 2 weeks at 8 months, and every week thereafter, using standardized protocols, forms, manuals, and codes (

26). Throughout the initial and repeat prenatal visits, interviewers collected reproductive and gynecological history, recent and past medical history, and family health and genetic history. They also conducted infectious disease and system review at the initial visit or as soon thereafter as possible. Physicians reviewed the data collected by the interviewer, collected further details on past and recent medical history, completed initial prenatal examination and observations, and recorded the date and listed any diagnoses unrelated to prenatal care that came to their attention. Medical and lay editing was subsequently carried out in conjunction with the participant’s complete hospital records by the obstetric coordinator or a board-certified obstetrician. Lastly, each participant’s study record and complete hospital records were summarized no later than 6 months after delivery.

Ascertainment of Exposure Status

The primary exposure variable included any bacterial infections that occurred during pregnancy, defined as the period between the estimated date of conception and the end of the third stage of labor. If women had more than one infection, they were counted only once using the Boolean OR operator. Infections that affected more than one major organ system were defined as multisystemic infections (e.g., sepsis), whereas those specifically affecting one system (e.g., vaginitis) were defined as localized infections. A total of 399 multisystemic and 3,201 localized infections during pregnancy were recorded. Localized bacterial infections included tuberculosis (N=8), pneumonia (N=83), syphilis (N=66), gonorrhea (N=15), kidney, ureter, and bladder infection (N=1,203), and vaginitis (N=2,136).

Assessment of Offspring With Schizophrenia and Related Psychoses

Cohort members with psychosis were identified between the ages of 32 and 39 through a systematic follow-up of the entire New England cohorts of the CPP from 1997 to 2003. The parents and offspring with a history of psychiatric hospitalization and/or possible psychotic or bipolar illness were identified from the following sources: record linkages with public hospitals, mental health clinics, and the Massachusetts and Rhode Island Departments of Mental Health; several follow-up and case-control studies nested within the larger New England cohort involving direct interviews; and reports from participants in these interview studies of family members with a history of psychotic or bipolar symptoms or diagnoses. Adult offspring in the New England cohorts with major psychotic disorders were identified through a two-stage diagnostic assessment procedure from 1996 to 2007, approximately 30 years after and blind to prior assessments. In stage 1, 249 individuals with possible psychotic illness were identified through systematic follow-up and subsequently diagnosed through administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (

27) (N=173) or review of medical charts alone (N=76). Based on interview data and medical record review, trained Ph.D.- and M.D.-level diagnosticians then made best-estimate consensus diagnoses according to DSM-IV criteria for lifetime prevalence of psychotic and other psychiatric disorders (

28). A total of 116 adult offspring were found to have a nonorganic psychotic disorder, including schizophrenia disorders (N=52; schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, depressive type), affective psychoses (N=53; schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, bipolar disorder with psychotic features, and major depressive disorder with psychotic features), and other nonaffective psychoses (N=11; delusional disorder, brief psychosis, and nonaffective psychoses, type not specified) (

11). Approval for the study was granted by institutional review boards at Harvard University, Brown University, and local psychiatric facilities. Written consent was obtained from all interviewed subjects, and they were compensated for their participation.

Covariates

Covariates included maternal race/ethnicity, study site, years of maternal education, parental socioeconomic index, and year and season of birth. A socioeconomic index, which was adapted from the Bureau of the Census and derived from the education and occupation of the head of household along with household income, was assigned to each pregnant woman; this continuous measure was later categorized in quartiles (

29). We further adjusted for reported parental history of mental illness (when we did not test for its effect modification) as a known risk factor for schizophrenia (

20) that has also been found to be associated with infections (

30). Previously, our group reported that the psychiatric history of both parents may independently predict offspring’s risk for psychotic disorders (

31). In this study, we operationalized genetic susceptibility to psychiatric disorder by aggregating the information collected from the mothers about their own as well as their spouse’s history of nervous problems requiring hospitalization, psychiatric treatment, or other therapy (i.e., clinically significant nervous problems) at two time points: during pregnancy and at the offspring’s age 7 visit. The overall rate of reported parental history of mental illness was 11%. Additionally, we adjusted for maternal exposure to viral infection during pregnancy to address potential confounding by concomitant viral infection. Lastly, we controlled for the offspring’s participation in the final follow-up of the larger CPP study—conducted at offspring age 7—given its observed association with the likelihood of being identified as a psychosis case subject in adulthood.

Statistical Analyses

We used chi-square and t tests (two-sided) to compare the demographic and perinatal characteristics of the exposed and unexposed mothers, and of the psychosis case subjects and non-case subjects. Logistic regression analyses were used to estimate odds ratios of psychoses for maternal exposure to any bacterial infections and to localized bacterial infections during pregnancy. Logistic regression models were adjusted for maternal neurological or psychiatric conditions during pregnancy, maternal education, parental socioeconomic index, maternal race/ethnicity, study site, season and year of birth, parental history of mental illness, offspring participation in the final follow-up of the larger CPP study, and concomitant viral infection during pregnancy. Exact logistic regression analyses were used to estimate the effects of multisystemic bacterial infection given the small number of case subjects exposed to this type of infection. In these models, we could only adjust for a few covariates that are reported to be key confounders in the hypothesized relationship and had strong statistical associations with both the exposure and the outcome in the analytic sample. Lastly, we examined effect modification of the hypothesized associations by offspring sex alone and presence of parental mental illness alone, using the Wald statistic. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

Sensitivity Analyses

Given that instances of maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy were not all serologically confirmed, some may have been misclassified (i.e., false positive). If a reported instance of bacterial infection was accompanied by any antibacterial treatment (e.g., chloramphenicol, erythromycin, nitrofurantoin, penicillin, streptomycin, tetracycline) and/or a physician’s diagnosis, we defined this as confirmed and conducted analyses considering only confirmed instances of bacterial infection. We assessed the robustness of our findings to potential misclassification of exposure by replicating the main effects with the confirmed instances of bacterial infection.

Results

Mothers who had bacterial infections during pregnancy were more likely to be nonwhite, unmarried, younger, and less educated; to have lower socioeconomic status; to reside in Providence; to have neurological or psychiatric conditions during pregnancy; and to report a history or a spouse’s history of clinically significant nervous problems, compared with mothers who had no bacterial infection during pregnancy (see

Table 1).

When examined with respect to psychosis status in adulthood, offspring case subjects were more likely to have at least one parent with a clinically significant mental illness and to have participated in the study’s age 7 assessment than non-case subjects (see

Table 2). Mothers of case subjects were more likely to be nonwhite, reside in Providence, have neurological or psychiatric conditions during pregnancy, and be less educated than mothers of non-case subjects.

Main Results

Of 15,421 cohort mothers in the analytic sample, 3,499 (23%) had bacterial infection; of these, 3,191 (21%) had localized infections, 399 (3%) had multisystemic infections, and 91 (<1%) had both. As shown in

Table 3, maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy was significantly associated with psychotic illnesses among adult offspring (adjusted odds ratio=1.8, 95% CI=1.2–2.7). Multisystemic bacterial infection was more strongly associated with offspring development of psychosis (adjusted odds ratio=2.9, 95% CI=1.3–5.9) than localized bacterial infection (adjusted odds ratio=1.6, 95% CI=1.1–2.3).

As shown in

Table 4, the association between prenatal exposure to any bacterial infection and subsequent psychosis was significantly modified by offspring sex. Male offspring were nearly three times as likely to develop a psychotic disorder after maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy, whereas female offspring showed no difference in the likelihood by the exposure status (males: adjusted odds ratio=2.6, 95% CI=1.6–4.2; females: adjusted odds ratio=1.0, 95% CI=0.5–1.9; p=0.018). Similarly, males were more than twice as likely to develop a psychotic disorder compared with females after maternal exposure to localized bacterial infection (males: adjusted odds ratio=2.1, 95% CI=1.2–3.4; females: adjusted odds ratio=1.0, 95% CI=0.5–1.9; p=0.084). Since there was only one female case subject exposed to multisystemic maternal bacterial infection, we reported results specific to males without evaluating statistical significance of effect modification. Males who were prenatally exposed to multisystemic infection had five times the odds of developing a psychotic disorder relative to unexposed males (adjusted odds ratio=5.0, 95% CI=2.0–10.7).

As shown in

Table 5, we observed a somewhat greater magnitude of hypothesized associations among offspring with reported parental mental illness compared with those without, but with no statistical support for effect modification.

Sensitivity Analyses

Of the 3,499 reported instances of bacterial infection, 1,785 (51%) were confirmed by a record of treatment with antibiotics and/or medical diagnosis. Of the 399 reported instances of multisystemic bacterial infection, 357 (89%) were confirmed. Of the 3,191 instances of localized bacterial infection, 1,513 (47%) were confirmed. Using the confirmed instances of bacterial infection, we were able to replicate the same patterns of associations from the main analyses. As expected, the magnitude of the hypothesized associations was slightly increased in the sensitivity analyses—potentially because of the reduction of nondifferential misclassification of exposure (see Tables S1–S3 in the online supplement).

Discussion

Maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy was significantly associated with subsequent development of schizophrenia and related psychoses among offspring. Localized bacterial infection predicted a 1.6-fold increase in the odds of developing a psychotic disorder in adulthood, and multisystemic bacterial infection predicted a nearly threefold increase in the odds. Furthermore, maternal bacterial infection was more strongly associated with the likelihood of developing psychosis among male than female offspring, and this effect modification was statistically significant for any bacterial infection (p=0.018) and approached significance for localized bacterial infection (p=0.084). However, these findings must be interpreted with caution given the overlapping confidence intervals of the sex-specific estimates. In addition, we found no statistical evidence for the hypothesized effect modification by reported parental mental illness, possibly because our measure of parental mental illness is a limited indicator of genetic risk.

Our findings in this study underscore the potential role of maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy in the etiology of psychotic disorders. Maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy has been found to induce the production of cytokines by the maternal immune system, the placenta, or the fetus itself (

32). Our group and others have found significant associations of prenatal levels of proinflammatory cytokines with the offspring’s risk of schizophrenia and related psychoses (

11,

33,

34), which, in a direct test, differed by sex (

11). Others have suggested that the effects of bacterial infection may not be specific to the prenatal period but that these findings implicate a generally increased familial susceptibility to infections, both during and outside pregnancy (

35). Although we cannot test this hypothesis with the CPP data, future studies may examine the effects of bacterial infection occurring before, during, and after pregnancy and ascertain their temporal specificity in psychosis risk.

Sex Difference in Schizophrenia and Related Psychoses

Our findings suggest that maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy may differentially affect the development of schizophrenia and related psychoses, depending on offspring sex. This is consistent with the long history from our group (

11,

36,

37) and others (

38) investigating sex differences in psychoses and relating disease risk, course, and outcome. Some have suggested a role of the placenta, in that the placenta of female fetuses may possess a greater ability to adapt to fluctuating in utero environmental conditions (such as prenatal immune challenges) compared with that of male fetuses (

39). However, the mechanisms underlying a male-specific vulnerability remain uncertain. Perhaps these effects could be due to reduced maternal-fetal compatibility for male fetuses, which may need to up-regulate immune-associated transcripts to resist an attack by the maternal immune system (

40). In a study of healthy fetuses, males had higher levels of cytokines indicative of a Th1-type (i.e., proinflammatory) response and expression of genes involved in the immune system and inflammation (

41). In contrast, females had higher levels of cytokines indicative of Th2-type (i.e., anti-inflammatory) response and expression of genes involved in immune regulation. On stimulation with bacterial endotoxin, levels of interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 were significantly higher in male than in female fetal blood samples (

42), consistent with our previous findings in maternal sera related to psychosis risk in males (

11). Given that these proinflammatory cytokines have long been implicated in schizophrenia and related psychoses, these findings further elucidate a potential pathway explaining male vulnerability to psychotic disorders with regard to maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy.

Strengths and Limitations

The major strength of this study is that reports of bacterial infection were obtained during pregnancy, and clinical diagnoses of schizophrenia and related psychoses among offspring were systematically gathered on the basis of chart diagnoses and in-person structured interviews with participants, allowing us to investigate prospective relationships between maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy and the offspring’s risk of psychotic disorders.

Our study also had some limitations. The first limitation is related to our case identification procedures and the resulting case series. The 116 case subjects (0.7% of the cohort) may not include all instances of schizophrenia and related psychoses in this cohort. In fact, our group was primarily seeking to enroll the most severe cases of psychotic disorders, and the anticipated prevalence of this subset of disorders was 2.4% (

43). In the study design phase, we excluded those who had organic or substance-induced psychosis to minimize false positive cases of psychotic disorders. In the analytic phase, we adjusted all statistical models for the effect of participation in the final follow-up assessment of the larger CPP study at offspring age 7—which was a strong predictor of being identified as a psychotic case subject in adulthood. Based on our previous examination of study participants, we conclude that this likely has an impact on the study’s statistical power, but we would not expect the completeness of ascertainment to differ in relation to prenatal infections. Owing to the limited power, we were not able to formally test effect modification for multisystemic bacterial infection and determine whether the findings are specific to schizophrenia, nonaffective psychosis, or other classes of psychosis.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that our subsample of case subjects identified through our record linkages with tertiary public hospitals tends to overrepresent persons with greater severity of conditions and lower socioeconomic status and to underrepresent high-functioning case subjects without hospitalization. In contrast, our subsample of case subjects identified through our direct follow-up and interview studies tends to overrepresent those with greater residential stability, levels of independent functioning, and socioeconomic status, as described in our earlier publication (

44). Given our use of various methods of case ascertainment, we do not expect any extreme bias toward persons of higher or lower illness severity, as both poles of the psychosis severity spectrum may have been slightly overrepresented in this study. Based on our group’s previous analyses of the considerable amount of information available from this longitudinal study (

12), it does not seem that the ascertained case subjects differ considerably from expectations, for instance, in terms of gender distribution, socioeconomic level, or family history of mental illness.

Another limitation pertains to the potential misclassification of exposure. Most previous studies have determined maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy on the basis of maternal self-reports or clinical records (

2–

4). Similarly, we used clinical records as the primary source of exposure information. Since the most prevalent types of bacterial infection are often asymptomatic, it is likely that some occurrences were not recorded and that only the more severe instances were included (

8). Several population-based studies have employed antibiotic use as a proxy of bacterial infection (

45). They demonstrated that a focus on antibiotic prescription and utilization allows for an ascertainment of a wide range of bacterial infections with different severity and potentially reduces false negatives. Inspired by this approach, we identified a subset of reported instances of bacterial infection that had corresponding medical diagnoses and/or a history of treatment with antibacterial medications and conducted sensitivity analyses. Possibly because of the reduction of nondifferential misclassification of exposure, the estimated effects of prenatal bacterial infection from the sensitivity analyses were slightly greater in magnitude than those from the main analyses.

Lastly, it is essential to note the possibility of other mechanisms that may interact with the biological mechanism examined in this study. In our analytic sample, prenatal bacterial infection was associated with several socioeconomic covariates, highlighting the importance of social factors in determining the occurrence of exposure. In fact, our group has previously reported that socioeconomic disadvantages during pregnancy—measured by parental education, income, occupation, and family structure—may significantly increase the risk for neurological abnormalities in offspring (

46). In a subsequent study, we reported that this association could be partially explained by socioeconomically driven variations in gestational immune activity, which was quantified using archived maternal sera collected during pregnancy (

47). In future studies, we may investigate the joint contribution of bacterial infection and socioeconomic disadvantage during pregnancy and potentially delineate a more comprehensive etiologic mechanism for schizophrenia and related psychoses.

Conclusions

There is considerable evidence that gestational viral infections during pregnancy have adverse consequences in offspring (

1). Our findings were consistent with this and extended previous work by demonstrating a significant impact of maternal bacterial infection during pregnancy on later risk for schizophrenia and related psychoses, which was particularly dependent on the severity of infection and offspring sex. These findings could be an important first step to motivating large-scale national register-based investigation of this type of research question. Larger samples would provide opportunities to address some of the crucial components on the etiologic pathway from prenatal bacterial infection to psychosis, such as gestational timing of exposure, sex-specific transmission of psychotic illness, specific subtypes of psychosis, and finer categorization of infectious exposure. If replicated, our findings would also call for public health and clinical efforts that focus on preventing and managing bacterial infection in pregnant women. It is crucial to evaluate both short- and long-term consequences associated with different types of bacterial infection and antibacterial medication to avoid untoward effects on the mother and fetus (

15,

48).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Monica Landi, M.S.W., and June Wolf, Ph.D., for their contributions to clinical interviewing and diagnoses, respectively, and Christiana Provencal for her contribution to project management during the original sample acquisition.