Recent neural models have proposed that hippocampal excitation-inhibition imbalance leads to the development of schizophrenia (

1–

3). Normal hippocampal function requires a balance of excitation and inhibition, governed by glutamatergic principal cells and GABAergic interneurons. Abnormalities in neurotransmitter systems (glutamate [

4,

5] and GABA [

6]) and inhibitory interneurons (

3,

7) have been identified as contributors to hippocampal dysfunction in schizophrenia. There is now converging evidence that such changes in hippocampal microcircuitry lead to hyperactivity, which may serve as both a critical regulator of neural circuits altered in schizophrenia (

8) and a candidate biomarker for psychosis (

9). Volume deficits emerge in the anterior hippocampus during the early stages of psychosis (

10) and in people at clinical high risk for developing a psychotic disorder (

11). Hyperactivity resulting from an excitation-inhibition imbalance is hypothesized to lead to this hippocampal volume deficit (

3,

4), but reliable, noninvasive neuroimaging markers of anterior hippocampal function in psychosis are lacking. Identifying and targeting functional changes in the anterior hippocampus before they progress to structural deficits during the critical period following illness onset is a crucial step in improving outcomes (

12).

Neuroimaging studies are ideally suited to testing the hypothesis of an excitation-inhibition imbalance in the anterior hippocampus because they can measure the net activity of principal cells and interneurons (

13). Anterior hippocampal hyperactivity has been consistently observed using cerebral blood volume (CBV) and cerebral blood flow in people with chronic schizophrenia (

14,

15) and high-risk individuals who progress to a psychotic disorder (

16,

17). In contrast, there is evidence for posterior hippocampal hyperactivity only in patients with chronic schizophrenia (

18,

19). CBV is regarded as the gold standard in vivo measure of baseline hippocampal activity (

20), but only three CBV studies of persons with psychosis have been published, with sample sizes of 18, 15, and 10 (

14–

16).

In this study, we set out to establish a robust, noninvasive, and feasible neuroimaging method to study hippocampal hyperactivity in psychosis. Meta-analyses of hippocampal resting-state connectivity (

21) and memory function (

22) indicate the presence of functional disturbances in chronic schizophrenia. The few task-based studies that have examined hippocampal function in early psychosis have produced mixed evidence for increased anterior hippocampal activation (

23) or decreased activation of anterior and posterior regions (

24,

25) during memory tasks. Critically, we do not know whether abnormal baseline hippocampal activity impairs task-related hippocampal function in the early stages of psychosis.

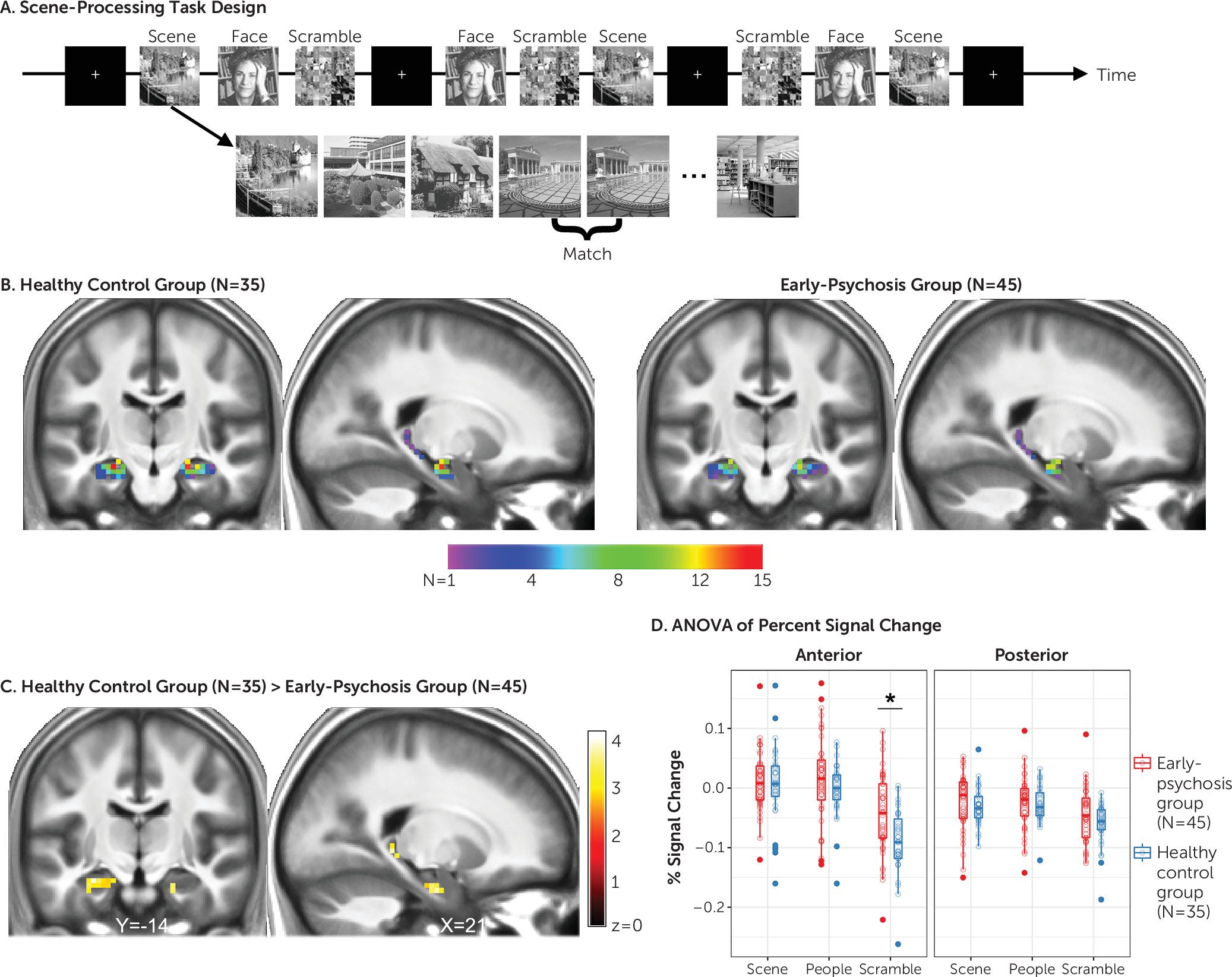

Here, we combined a scene-processing functional MRI (fMRI) task that reliably activates the hippocampus in healthy individuals with CBV imaging to test the hypothesis that anterior hippocampal hyperactivity in psychosis limits functional recruitment during task performance. Recent work has demonstrated that the anterior hippocampus has a role in both perceptual scene processing and construction of mental scenes (reviewed in reference

26). Anterior hippocampal response to scenes is reliably measurable at the single subject level (

27) and is not related merely to memory-related functions (

28). We hypothesized that in early-psychosis patients, decreased activation of the anterior hippocampus during scene processing stems from increased baseline activity that limits effective recruitment of this region during task performance. These data may help resolve existing discrepancies regarding the nature of hippocampal dysfunction in early psychosis.

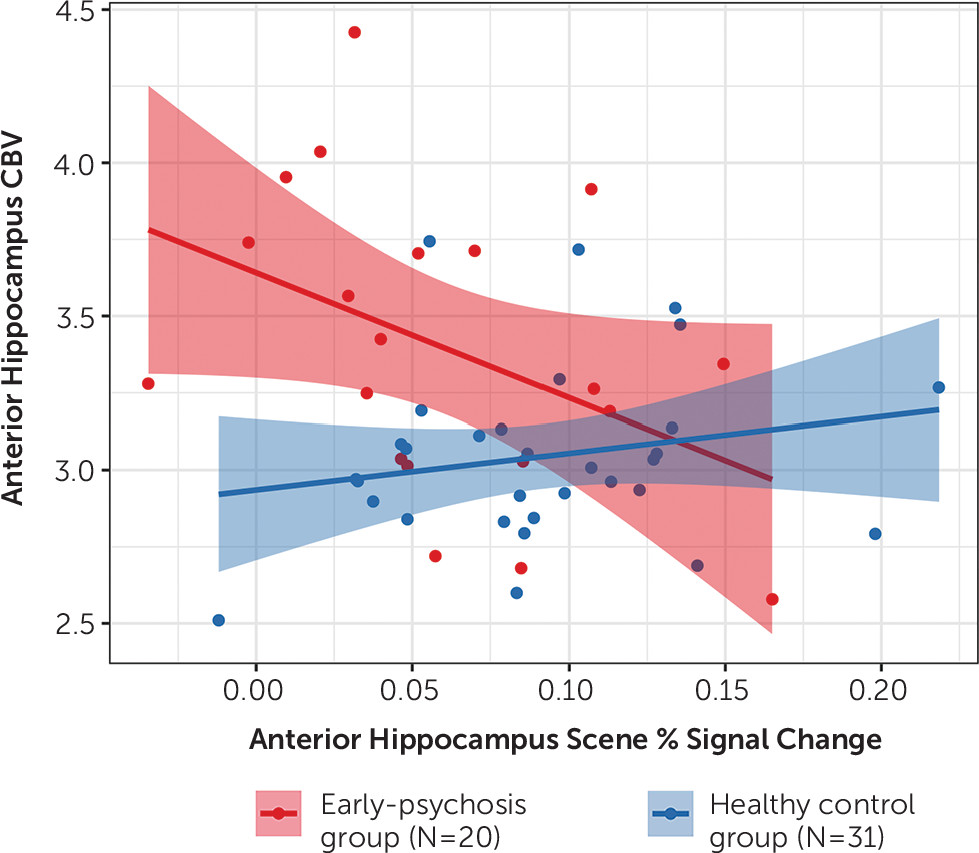

Discussion

Our study provides compelling evidence that anterior hippocampal activation is impaired in early psychosis and that this impairment is related to underlying hyperactivity. These findings form a critical translational bridge between basic research studies of anterior hippocampal activity as a neural substrate for psychosis (

1) and functional MRI studies in patients, where it is typically unclear how findings of hyper- versus hypoactivation relate to underlying metabolism and activity.

Preclinical data suggest that the anterior hippocampus, and the subiculum in particular, may be a primary driver in the pathophysiology of psychosis through its modulation of dopaminergic tone (

8). Two recent studies using high-resolution fMRI found that the anterior subiculum, rather than the adjacent cornu ammonis or dentate gyrus subfields, is involved in scene perception (

28,

34). Consequently, the task used in the present study appears to be uniquely suited to detecting changes in the region hypothesized to induce dopaminergic dysfunction in psychosis. Our findings provide novel evidence that hyperactivity and the associated reduced activation of the anterior hippocampus can be studied with a simple and brief task. However, high-resolution fMRI is needed to confirm anterior subiculum (rather than broad hippocampal) dysfunction during scene processing in psychosis. Notably, scene-processing tasks like the one used in our study can reliably elicit anterior hippocampal activation at the single subject level (

27), which suggests the possibility that scene processing could be used as a neuroimaging biomarker for treatment development and early detection of psychosis (

9).

Existing preclinical studies support anterior hippocampal hyperactivity both as a therapeutic target and as an early detection marker for psychosis. Prenatal insults to the hippocampus give rise to a psychosis-like phenotype in adolescent and adult rodents (

8). Critical work by Grace, Lodge, and colleagues has shown that the hippocampal excitation-inhibition imbalance and hyperdopaminergic state present in this preclinical model can be restored by pharmacological interventions (including benzodiazepines [

35], alpha-5 GABA-A [

36], and alpha-7 nicotinic receptor modulators [

37]), deep brain (

38) and vagal nerve stimulation (

39), and cell-based therapies (

40). In line with this basic research, Tregellas et al. have demonstrated across multiple imaging paradigms that nicotinic agents can reduce hippocampal activation in patients (reviewed in reference

41). Additional work from animal studies has shown that reducing hippocampal hyperactivity in adolescent animals has the potential to forestall illness onset (

35) and improve cognitive deficits in adulthood (

42). If hippocampal dysfunction in schizophrenia develops in stages (

3), then detection of hippocampal hyperactivity before changes in structure occur may offer the best opportunity to intercede and halt illness progression. In order to establish whether the scene-processing task can be used as a biomarker, future work must demonstrate its reliability in patients, sensitivity to illness staging and progression, and response to both existing and novel therapies.

To our knowledge, no studies have yet tested explicitly whether there is impaired anterior hippocampal activation during scene processing in psychosis. Several task-based fMRI studies that have observed altered anterior hippocampus activation in psychosis have used scenes as stimuli (

23,

24,

43). Although these studies focused on examining disruption of hippocampus-mediated memory functions, an alternative possibility is that the tasks engaged scene-processing mechanisms within the hippocampus. The present study replicates and extends the recent findings by Francis et al. (

24), who reported decreased activation of the anterior hippocampus of early-psychosis patients during a scene-encoding task. Although that study examined scene processing in the context of memory encoding and retrieval, the area of reduced activation they detected in patients is nearly identical to the one reported here. In a separate study, Ragland et al. (

23) observed increased activation of the anterior hippocampus during item changes of scenes in patients with schizophrenia. Their task required comparison of fine details in the context of spatial processing, consistent with hypothesized functions of the posterior, rather than anterior, hippocampus (

44). Close examination of their data reveals that the increased anterior hippocampal response in patients occurred in the context of no differences in activation for the same contrast in control subjects (see Figure 2 in reference

23). Collectively, this pattern of findings is consistent with underlying hyperactivity in patients manifesting as hypoactivation during tasks that elicit anterior hippocampal activation in healthy control subjects and hyperactivation during tasks that do not activate the anterior hippocampus in healthy control subjects.

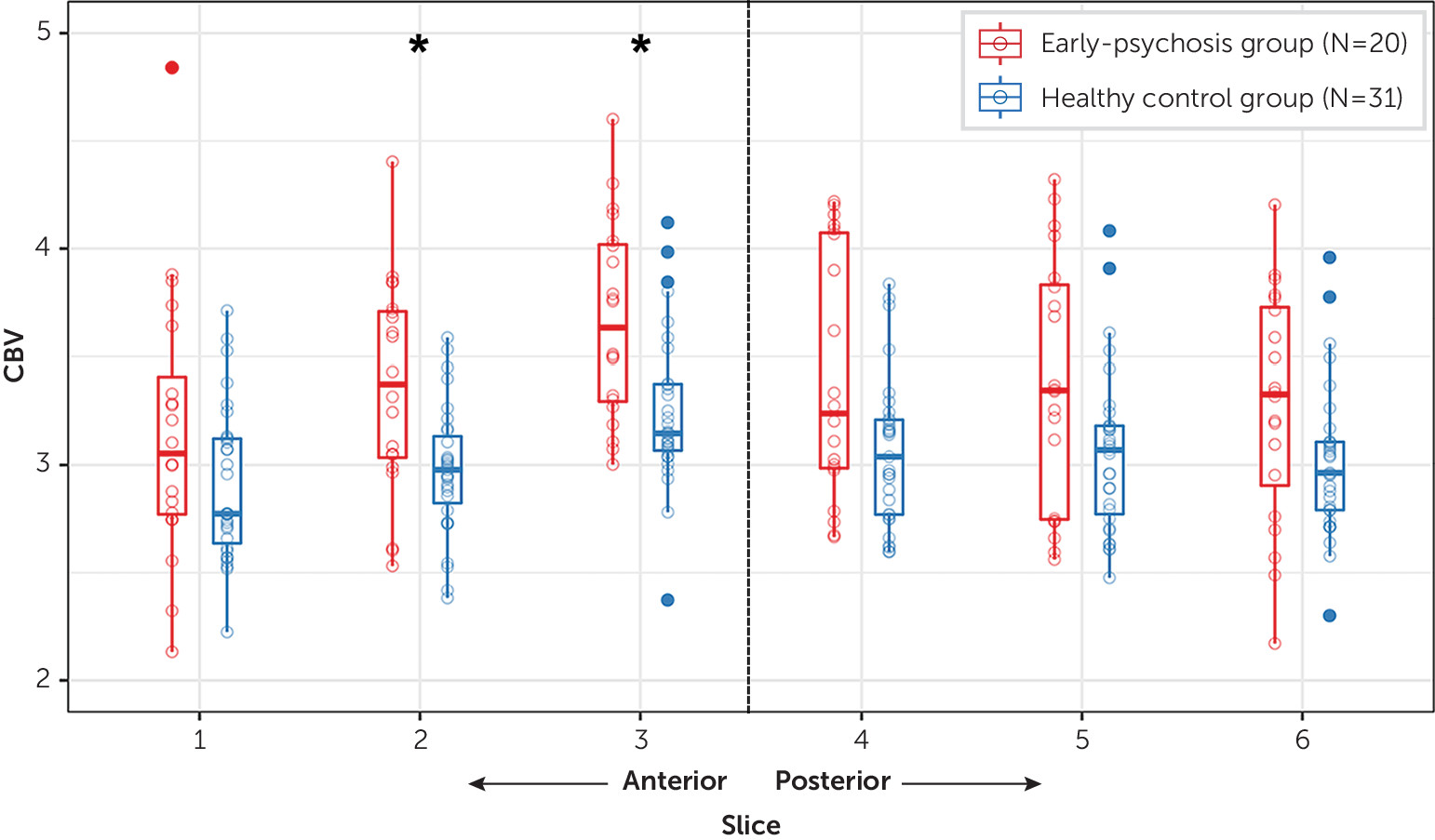

Our results provide an important link between findings from persons at high risk for psychosis, where sample sizes are limited by low rates of conversion to clinical psychosis, and studies of patients with chronic psychosis, where long-term medication effects are a significant confounder. We observed increased CBV primarily in the anterior hippocampus of patients in the early stages of psychosis, consistent with previous findings in high-risk individuals (

16). Although we observed significant between-group differences in CBV only in the anterior hippocampus, subthreshold differences may be present in the posterior hippocampus. Indeed, two slices in the midbody of the hippocampus (slices 4 and 5; see

Figure 4) showed increased CBV that was significant at p<0.05 before correction for multiple comparisons. The majority of patients in the present study were examined during or soon after their first psychotic episode (

Table 1). These data provide partial support for the hypothesis that there is a spreading of hippocampal dysfunction during psychosis progression (

3,

4). Alternatively, heterogeneity may exist within the patient cohort such that hyperactivity is characteristic of a subset of patients, rather than serving as a global illness biomarker. Longitudinal studies are needed to clarify which of these possibilities is more likely.

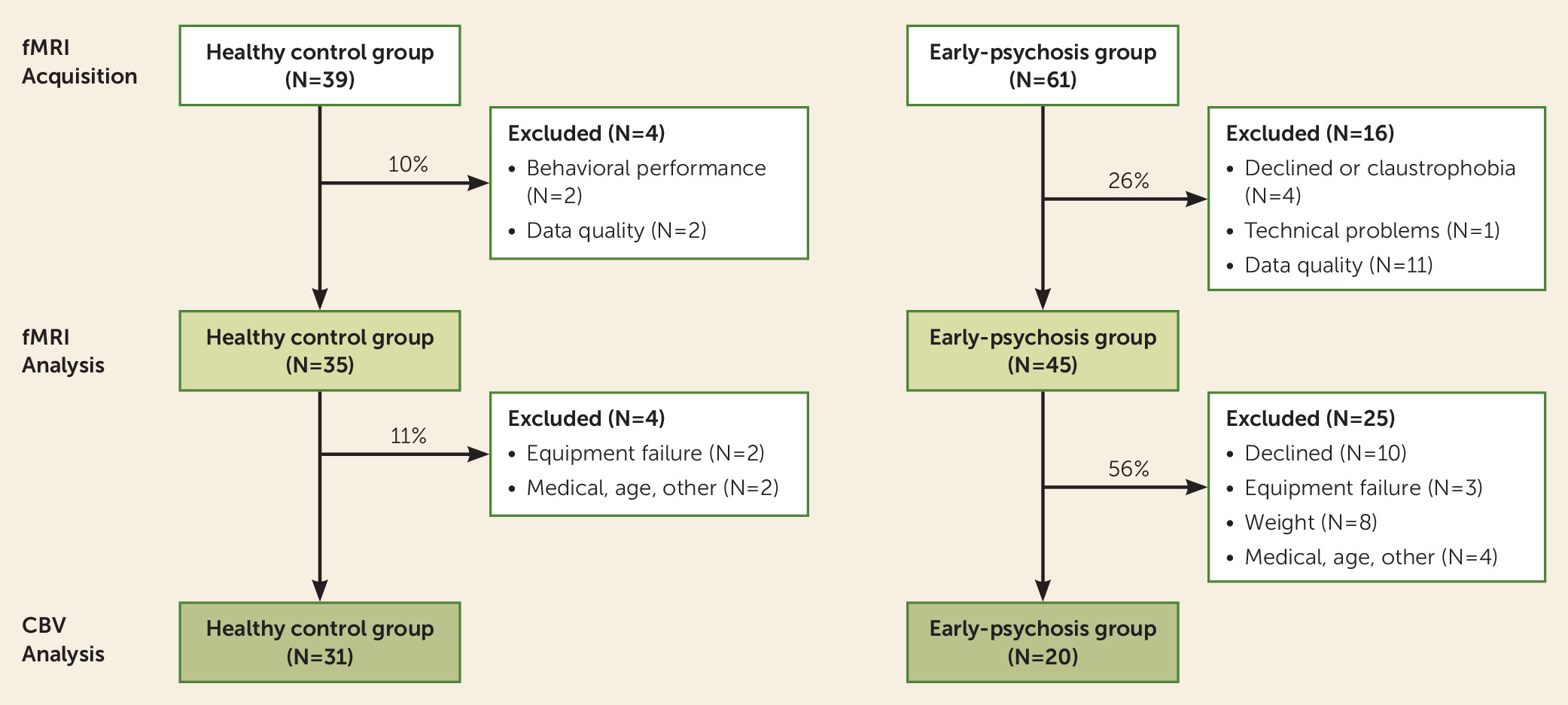

The strengths of our study include a large cohort of patients in the early stages of a nonaffective psychotic illness and the use of multimodal neuroimaging of anterior hippocampal function. Our study is limited primarily by the relatively small number of individuals for whom both fMRI and CBV data were available. However, to our knowledge, this sample is the largest CBV imaging data set acquired in patients with a psychotic disorder. Seminal work by Schobel, Small, and colleagues (

14,

16) (schizophrenia patients, N=18, and psychotic disorder, N=10, respectively) and previous work by our group (

15,

45) (schizophrenia patients, N=15) has examined hippocampal hyperactivity in prodromal or high-risk individuals and in individuals with established schizophrenia, but the present study is the first to demonstrate anterior hippocampal hyperactivity in early psychosis. In comparison to fMRI, CBV imaging presents several challenges that likely preclude its use as a repeatable measure of hippocampal function for longitudinal studies of psychosis, illness staging, and assessment of treatment effects. Many patients decline to participate in a CBV study because of its invasive nature (28% of those eligible for the present study). CBV imaging also has weight and kidney function requirements that can limit the participation of patients treated with antipsychotic medications. An additional limitation is that we observed a relationship between CBV and task-related activation only in the patient group. It is possible that there is not enough CBV variability within the healthy control subjects to detect such an association. However, the absence of a correlation in healthy control subjects is consistent with other hippocampus-related deficits in schizophrenia (

46). Finally, we did not examine how the present findings relate to possible alterations in other brain regions, including medial prefrontal cortex function (

17). Future studies should examine whether there is an association between GABA concentration in the medial prefrontal cortex and task-related anterior hippocampal dysfunction.

In summary, using a multimodal imaging approach, we found novel evidence for anterior hippocampal dysfunction in early psychosis. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine the relationship between the observed functional differences and subsequent structural changes in the hippocampus and outcomes of patients with psychosis.