Childhood maltreatment dramatically increases the risk for psychopathology in adulthood. This association appears to be particularly pronounced for psychiatric disorders associated with social avoidance, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and mood disorders (

1). Accumulating evidence indicates that childhood maltreatment negatively affects adult social functioning, which in turn confers vulnerability to future psychiatric morbidity (

2). Specifically, childhood maltreatment often manifests in dysfunctional interpersonal behavior, including not only social withdrawal and isolation (

3) but also aggressive and antisocial tendencies (

4).

A large body of research points toward the biological embedding of early psychosocial adversity as an etiological link between childhood maltreatment and psychopathology (

5). Imaging studies have found that childhood maltreatment is associated with hyperresponsiveness to threatening faces in the amygdala and insula (

6) and hypoactivation to reward signals in the hippocampus and insula (

7). Moreover, morphological studies have consistently linked early psychosocial adversities to anatomical alterations in sensory systems and large-scale networks associated with social threat detection and stress response (

5), including in the hippocampus and insula (

8). Surprisingly, however, it is still unknown whether childhood maltreatment and the associated neuroplasticity have detrimental effects on key processes of social interactions such as interpersonal distance and social touch.

Interpersonal distance is automatically regulated during social interactions, and intrusions into the personal space induce a sense of threat and discomfort (

9). Converging evidence suggests that the regulation of interpersonal distance is amygdala dependent (

10) and functions as a control mechanism to regulate arousal and stimulation intensity during social interactions (

11). Previous research found a preference for larger interpersonal distance in physically abused children (

12) and adults with PTSD (

13), an association that may be explained by higher trait-like levels of sensory sensitivity (

14) in individuals with traumatic experiences.

Social touch is a crucial source of sensory experience that shapes trajectories of brain development, promotes a sense of body ownership, and serves as a homeostatic regulator of acute stress (

15). The perception of interpersonal touch acts on both sensory and emotional systems via different low-threshold mechanoreceptor afferents in hairy skin. Aβ-fibers conduct high-speed impulses (50 m/s) that relay discriminative tactile information, whereas C-tactile (CT) fibers primarily convey affective properties of touch at slow stimulation velocities (1–10 cm/s) (

15). While both tactile stimulation velocities elicit activations in the primary somatosensory cortex and the insula, fast speed tactile stimulation is more likely to activate the primary somatosensory and slow speed tactile stimulation is more likely to activate the posterior insula (

16), the key hub for interoceptive processing (

17). Altered touch sensitivity has been observed in a variety of psychiatric disorders, including anorexia nervosa (

18) and autism spectrum disorder (

19).

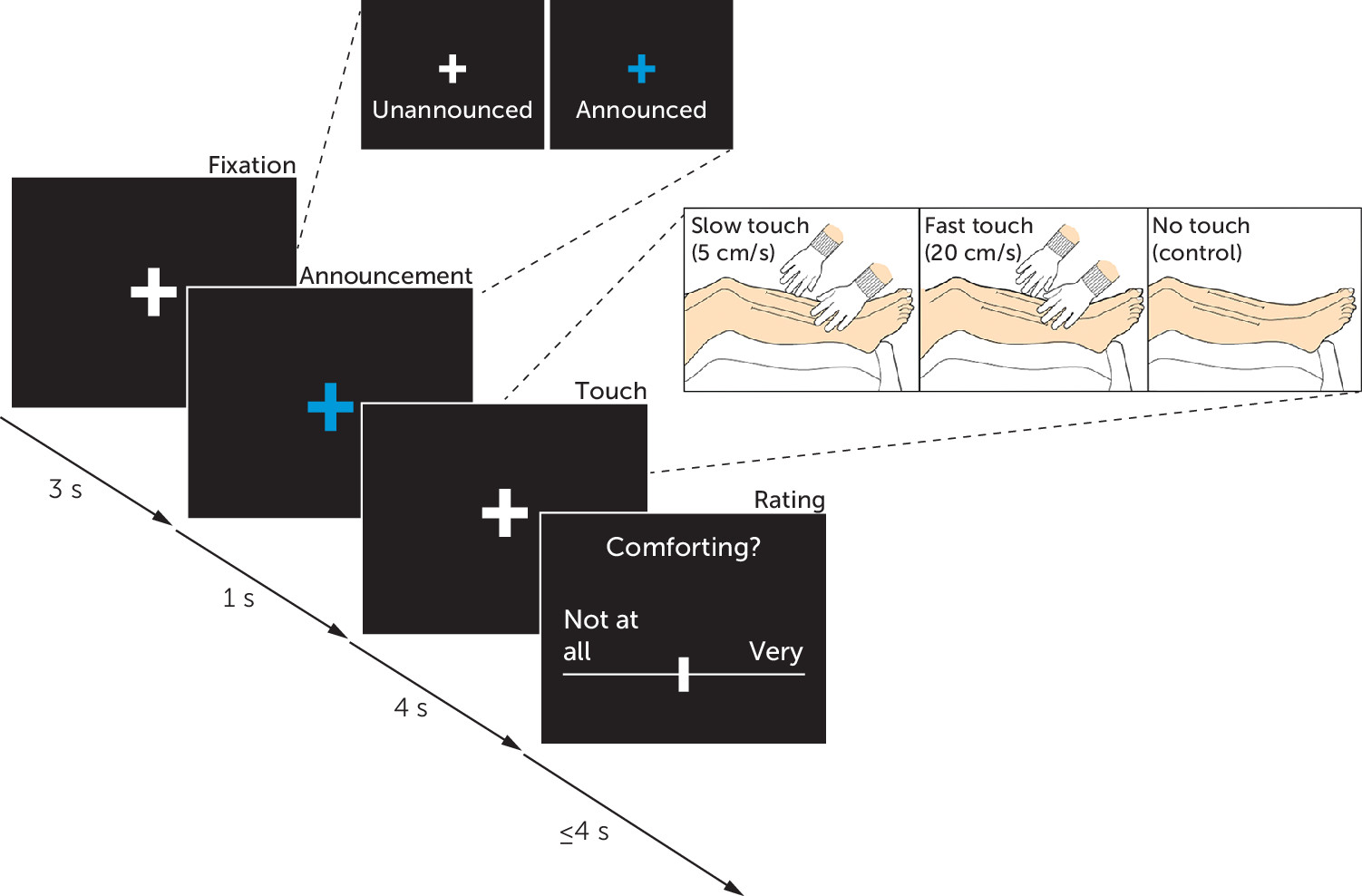

The rationale of the present study was to examine interpersonal distance preferences and social touch processing as core metrics of social interactions in individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment. Participants with varying degrees of childhood maltreatment first participated in an established interpersonal distance task and subsequently underwent a social touch paradigm with concomitant functional MRI (fMRI), during which participants rated the comfort of affective (i.e., slow) and discriminative (i.e., fast) touch. Additionally, we used voxel-based morphometry (VBM) to study childhood maltreatment–associated region-specific differences in gray matter volume. We hypothesized that participants with severe childhood maltreatment experiences would prefer larger interpersonal distances and perceive social touch as less comfortable compared with participants with no or marginal childhood maltreatment experiences. We expected that these effects would be accompanied by diminished neural responses to slow touch and heightened responses to fast touch in the primary somatosensory cortex, insula, hippocampus, and amygdala. Furthermore, we explored whether structural changes or childhood maltreatment–associated symptoms such as depression and PTSD scores moderated or mediated the effects of childhood maltreatment.

Discussion

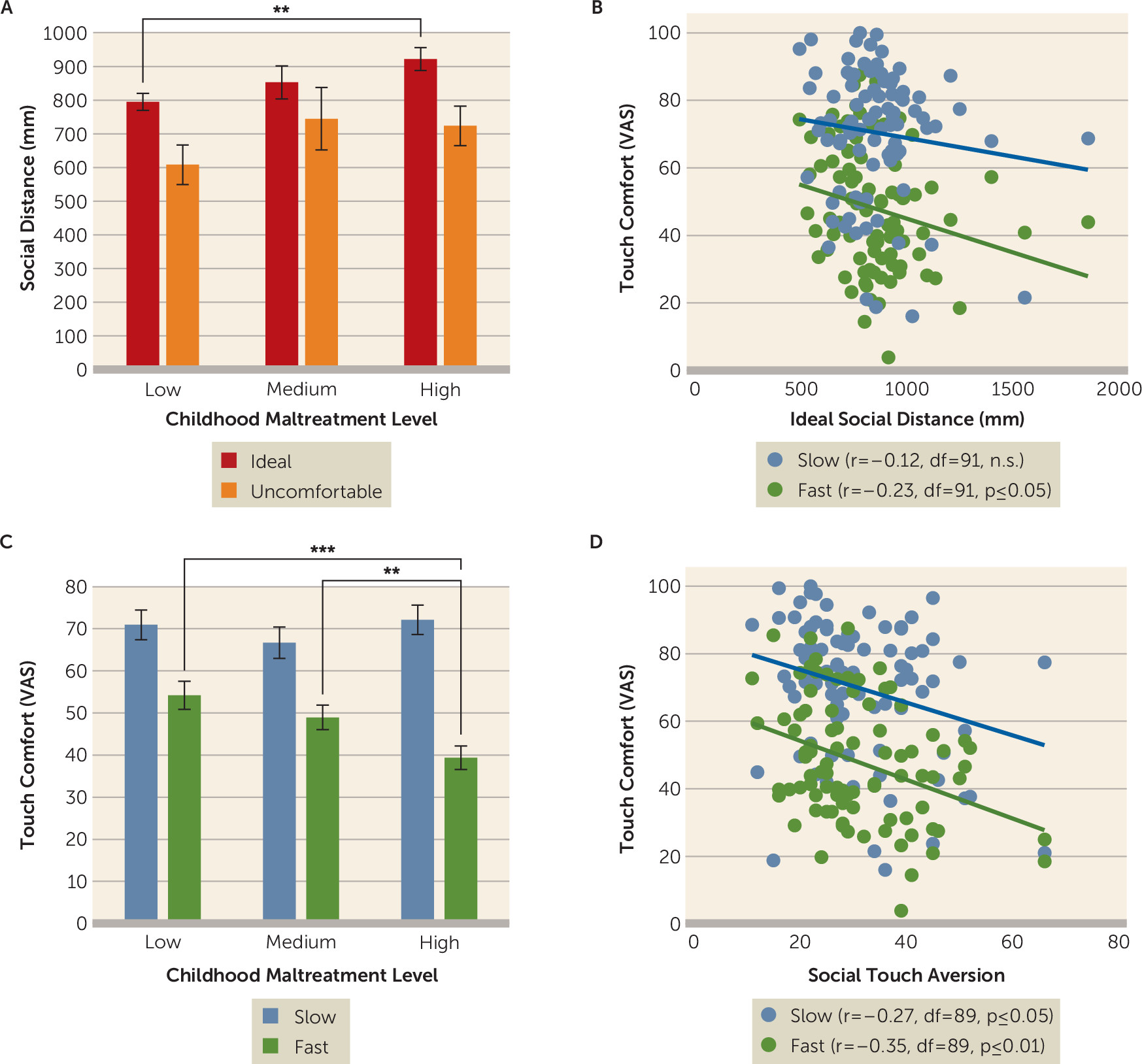

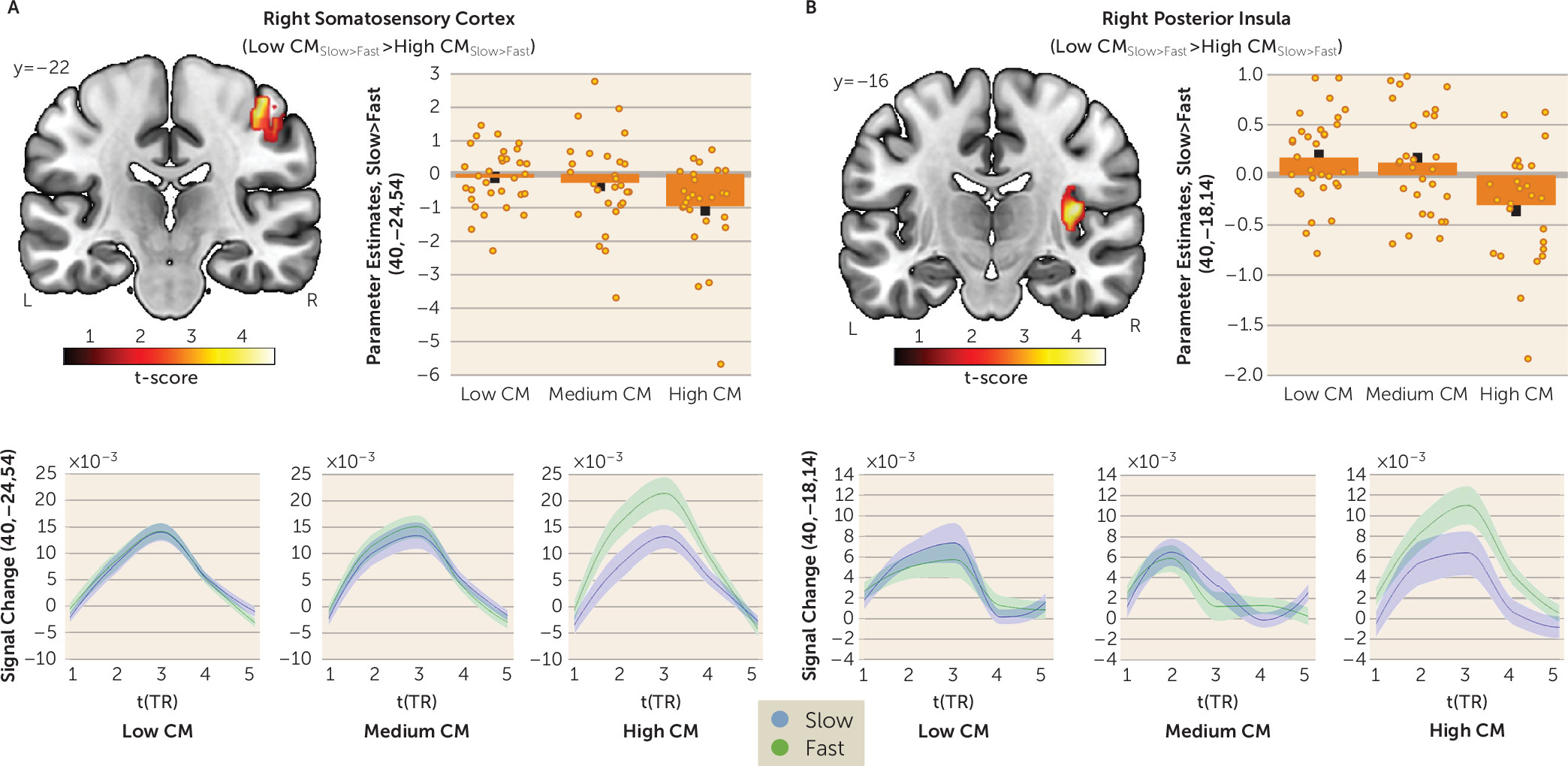

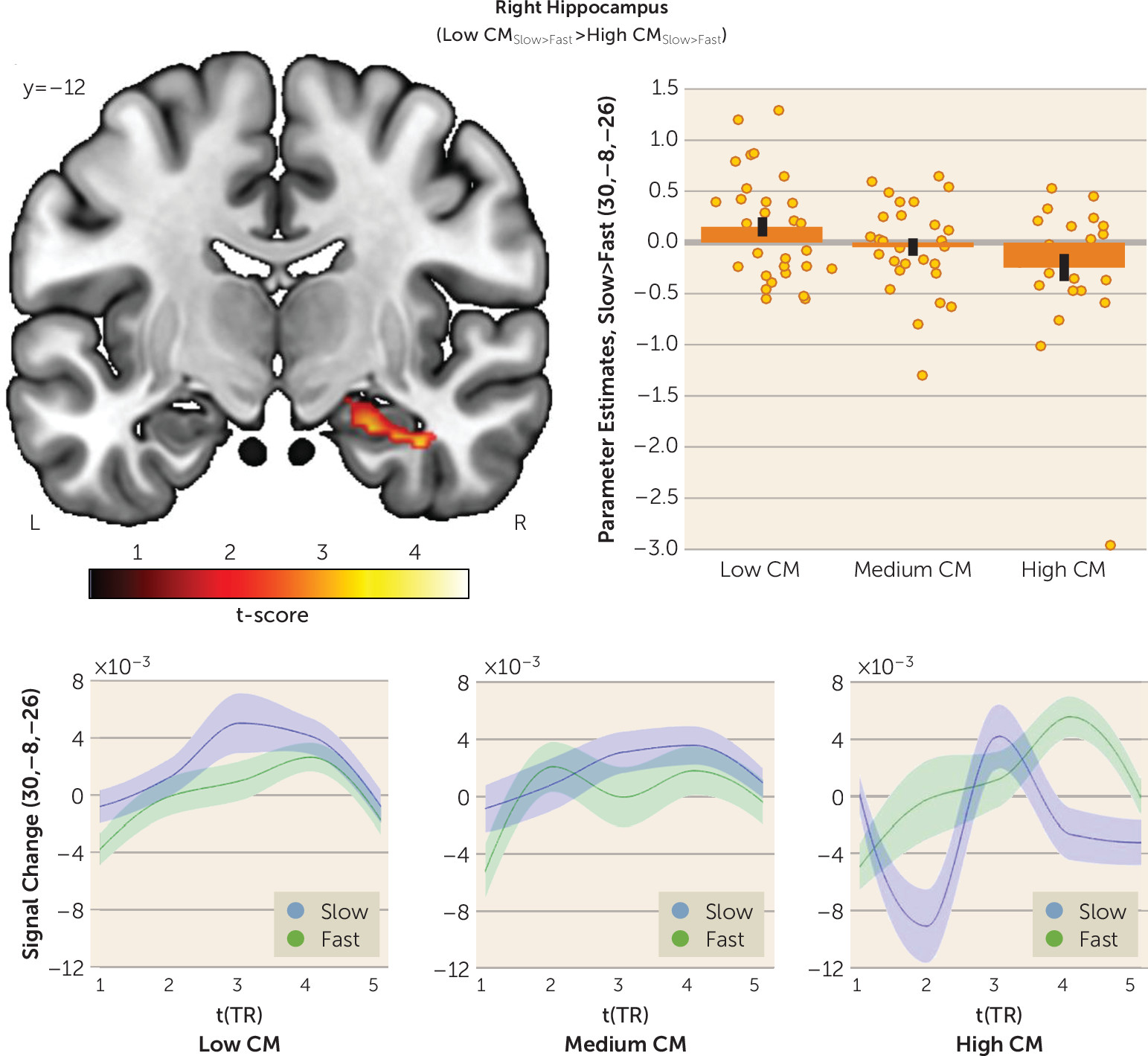

In this study, we investigated whether childhood maltreatment is associated with altered interpersonal distance preferences and social touch processing later in life. As hypothesized, participants with a high level of childhood maltreatment preferred larger interpersonal distance in a stop-distance paradigm. Participants with severe childhood maltreatment also expressed discomfort of discriminative (i.e., fast) touch in an fMRI social touch paradigm, which was paralleled by increased responses to fast touch in the right primary somatosensory cortex and posterior insula and diminished responses to affective (i.e., slow) touch in the right hippocampus. Our findings add to the burgeoning evidence indicating that childhood maltreatment has long-term detrimental effects on sensory processing of social information (

5,

29).

Previous research demonstrated that a higher perceived risk of physical threat is associated with larger interpersonal distance, which may facilitate escape during potentially violent interactions (

30). It is well established that individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment exhibit increased sensitivity to threat (

29), and therefore they may use the self-protective and arousal regulation functions of larger interpersonal distance (

11) to mitigate emotional and physical threats during interactions. Thus, a need for a larger personal space may constitute another dimension of the phenotypic hypervigilance to threat signals following childhood maltreatment (

29). Furthermore, our finding of larger interpersonal distance preferences in individuals with high childhood maltreatment levels were linked to both general touch aversion and perceived discomfort of discriminative touch, indicating overall avoidance of interpersonal sensory stimulation to reduce emotional distress.

On the neural level, childhood maltreatment–associated responses to social touch suggest a cortical sensory hyperreactivity in the primary somatosensory cortex and posterior insula in response to discriminative touch alongside a CT-specific hypoactivation in the hippocampus. The primary somatosensory cortex has a functional role for motor control (

15), and exaggerated primary somatosensory cortex responses have been associated with tactile defensiveness (

31). Thus, increased primary somatosensory cortex activation to discriminative touch may reflect a motor preparation to initiate a flight response. The insula encodes interoceptive signals from the body and integrates these signals in a posterior-to-anterior fashion, ultimately serving emotional and body awareness (

17). Moreover, hyperreactivity of the posterior insula has been observed in trauma-exposed adolescents in response to conflicting visual stimuli (

32), which may indicate increased salience detection of external signals, consistent with the proposed function of the posterior insula as a multisensory magnitude detector in the context of pain perception (

33). In the present study, increased posterior insula activation was associated with diminished comfort of fast touch, suggesting that this potentiated sensory signal may contribute to an interoceptive integration and awareness that make individuals with high childhood maltreatment levels feel tense and uneasy. In addition to these sensory effects, we observed changes in limbic touch responsiveness. The hippocampus plays a crucial role in the consolidation and retrieval of episodic memory (

34) and is highly susceptible to early stress (

5). Furthermore, a population of reward-associated cells has been identified in the hippocampus (

35), and activation in this region is altered in the context of rewarding stimuli (

35,

36). Thus, childhood maltreatment–associated hippocampal hypoactivation may reflect decreased encoding of affective touch as a result of the retrieval of past experiences of abuse and neglect when affective touch was initially associated with low reward salience. Moreover, we found a decrease in amygdala responses to affective touch, although it fell short of significance. Recent neuroimaging studies suggest that the amygdala may extract the emotional value of somatosensory inputs (

37) and show diminished amygdala response to positive facial stimuli in individuals with childhood maltreatment (

8). Reduced amygdala responses to CT-optimal affective touch may therefore reflect diminished emotional salience of positive social signals.

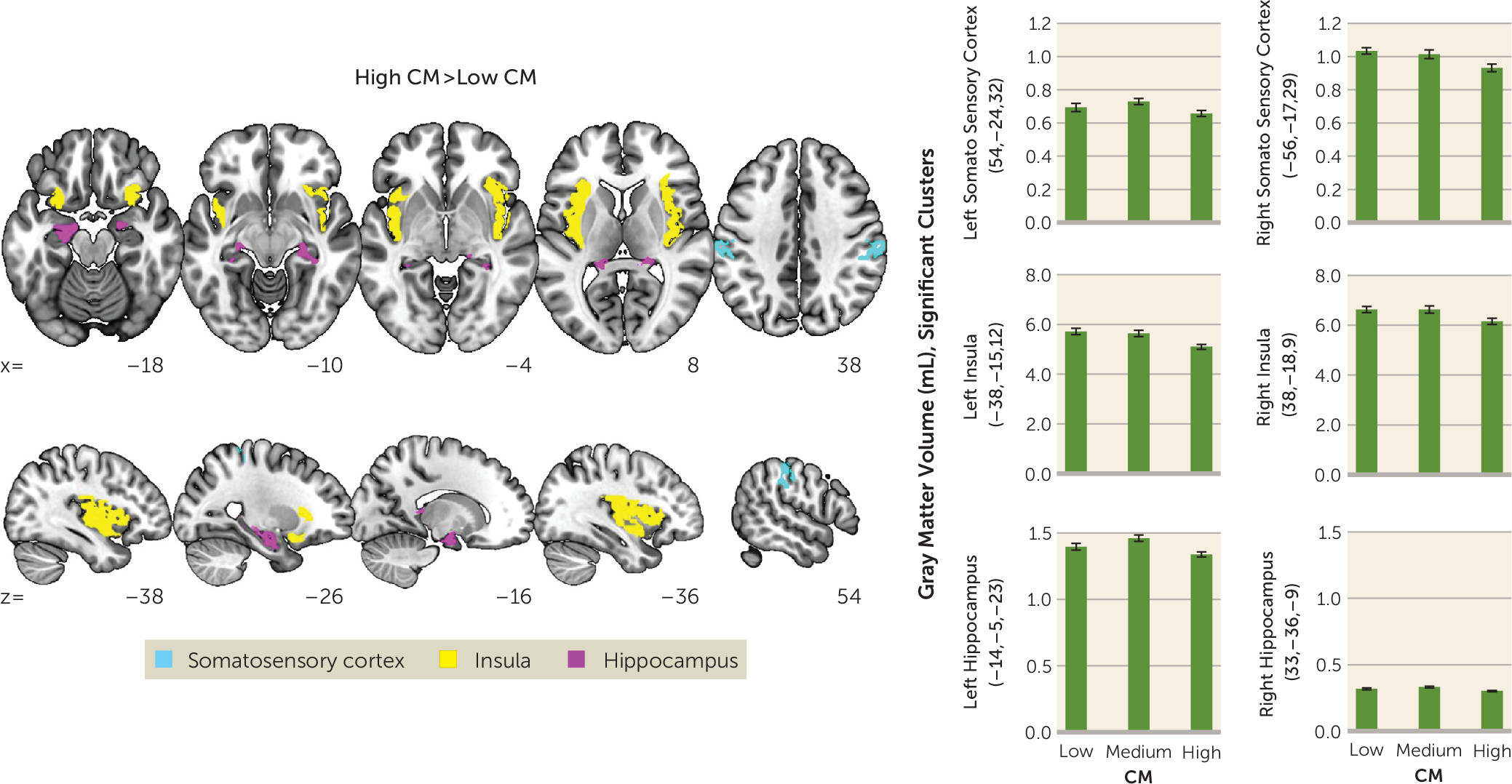

Our findings of childhood maltreatment–associated structural deficits mirror previous reports of childhood maltreatment–associated reduction of gray matter volume in the hippocampus, primary somatosensory cortex, insula (

8), and amygdala (

38). Both childhood maltreatment–associated hippocampal and amygdala volume reductions have been linked to behavioral disturbances later in life (

38). Interestingly, modifications of sensory systems may convey the specific forms of early adverse experiences (

5). Thus, childhood maltreatment–associated structural deficits in the primary somatosensory cortex and insula may reflect neuroplastic adaptations as a function of early physical abuse and/or touch deprivation to promote avoidance and diminish approach responses toward traumatic reminders (

5). Notably, structural changes neither moderated nor mediated the observed response pattern to social touch, underscoring the hypothesis that structural modifications may keep functional adaptation pathways intact to allow for rapid threat responses (

5).

Furthermore, significant detrimental effects on interpersonal distance and social touch were evident in participants with severe childhood maltreatment, whereas a medium level of childhood maltreatment did not produce significant changes. This response pattern corroborates previous findings of a dose-dependent effect of childhood maltreatment on psychosocial functioning and comorbidity (

39). Moreover, avoidance tendencies toward everyday social touch appear to hinder individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment from experiencing the stress-buffering effects of physical contact. It is noteworthy that the announcement of the subsequent touch did not significantly reduce childhood maltreatment–associated changes in response to social touch. Thus, the childhood maltreatment effect on social touch and physical proximity cannot be explained only as a consequence of biased cognition (

29) but should also be considered a product of fundamentally altered sensory experiences.

Our results may have important implications for the understanding and effective treatment of childhood maltreatment and associated psychopathology. Adults with a history of childhood maltreatment may exhibit exaggerated responses to interpersonal physical contact, which in turn may affect their psychosocial functioning in daily life. Hypersensitivity and sensory avoidance have been linked to social withdrawal and an inability to initiate relationships (

40). Moreover, hyperresponsiveness to touch was found to fully mediate social impairments in autism spectrum disorder (

19), suggesting that sensory dysregulations in the tactile domain may confer vulnerability to interpersonal difficulties. Recent findings demonstrated that sensory profiles mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and health-related quality of life in patients with affective disorders (

41). Furthermore, neural hyperresponsiveness to aversive facial stimuli has been shown to predict poor treatment response in PTSD (

42). Thus, randomized clinical trials are warranted to evaluate treatment-induced changes and the predictive validity of social touch and physical proximity. Current cognitive-behavioral therapeutic approaches do not directly address these aberrant autonomic and somatic responses. Previous research has, however, demonstrated the effectiveness of massage interventions in the treatment of patients with sexual abuse (

43) and PTSD (

44). Along these lines, the use of complementary bottom-up, body-based interventions could help individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment to facilitate their participation in social interactions by learning to tolerate and enjoy the comforts of social touch in a safe environment (

45).

Limitations of this study include the co-occurrence and interrelatedness of multiple childhood maltreatment types in the sample, which hindered us from disentangling the effects of specific types of maltreatment. However, childhood family adversities are often clustered, rendering multitype maltreatment highly prevalent in the population (

39). Another limitation is the retrospective and self-report nature of childhood maltreatment assessment, which may be subject to negative recall bias due to current elevated levels of depression and psychological distress (

46). Although we thoroughly controlled for current depressive symptoms and subjective stress levels, a recall-related underreporting of childhood maltreatment may have influenced our results.

In conclusion, we provide first evidence that severe childhood maltreatment is associated with larger interpersonal distance preferences and adverse responses to social touch. We propose changes in early sensory processing as the underlying mechanism of these associations. This sensory dysregulation may explain why individuals with severe childhood maltreatment often suffer from difficulties in establishing and maintaining close social bonds later in life.