Psychotic disorders have a lifetime prevalence of approximately 3% (

1) and have a substantial impact on individuals, their families, and society. While psychotic disorders are defined in part by the presence of psychotic experiences, psychotic experiences commonly occur outside the context of a full psychotic disorder (

2). Studies using semistructured interviews, which are similar to the cross-questioning style of clinical practice, report 6-month prevalence estimates of approximately 5% in late childhood or adolescence (

3–

5), although estimates from fully structured interviews and questionnaires are generally higher (

2).

In the general population, the vast majority of people with psychotic experiences do not present to clinical services, let alone with a psychotic disorder (

4,

6–

8). While psychotic experiences are usually transient (

7,

9–

14), they are nevertheless often distressing and associated with impaired social and occupational function, both concurrently and longitudinally (

4,

15,

16), and with suicidality (

17–

21); thus, psychotic experiences may index a common, and underrecognized, public health burden (

4,

22). Given the global burden of disease of psychotic disorders and the promise of benefit from early intervention in improving clinical outcomes, there is an imperative to understand the developmental trajectories from onset of psychotic experiences to clinical disorder and to improve identification of individuals at greatest risk of requiring intervention.

The aims of this study were 1) to describe the change in incidence of psychotic experiences in the general population from ages 12 through 24; 2) to describe the prevalence of at-risk mental states for psychosis and psychotic disorder at age 24 and to quantify the likely burden of unmet clinical need among young adults in the general population; and 3) to examine the predictive ability of both self-reported and interviewer-rated measures of psychotic experiences during childhood and adolescence in identifying psychotic disorder by age 24.

Results

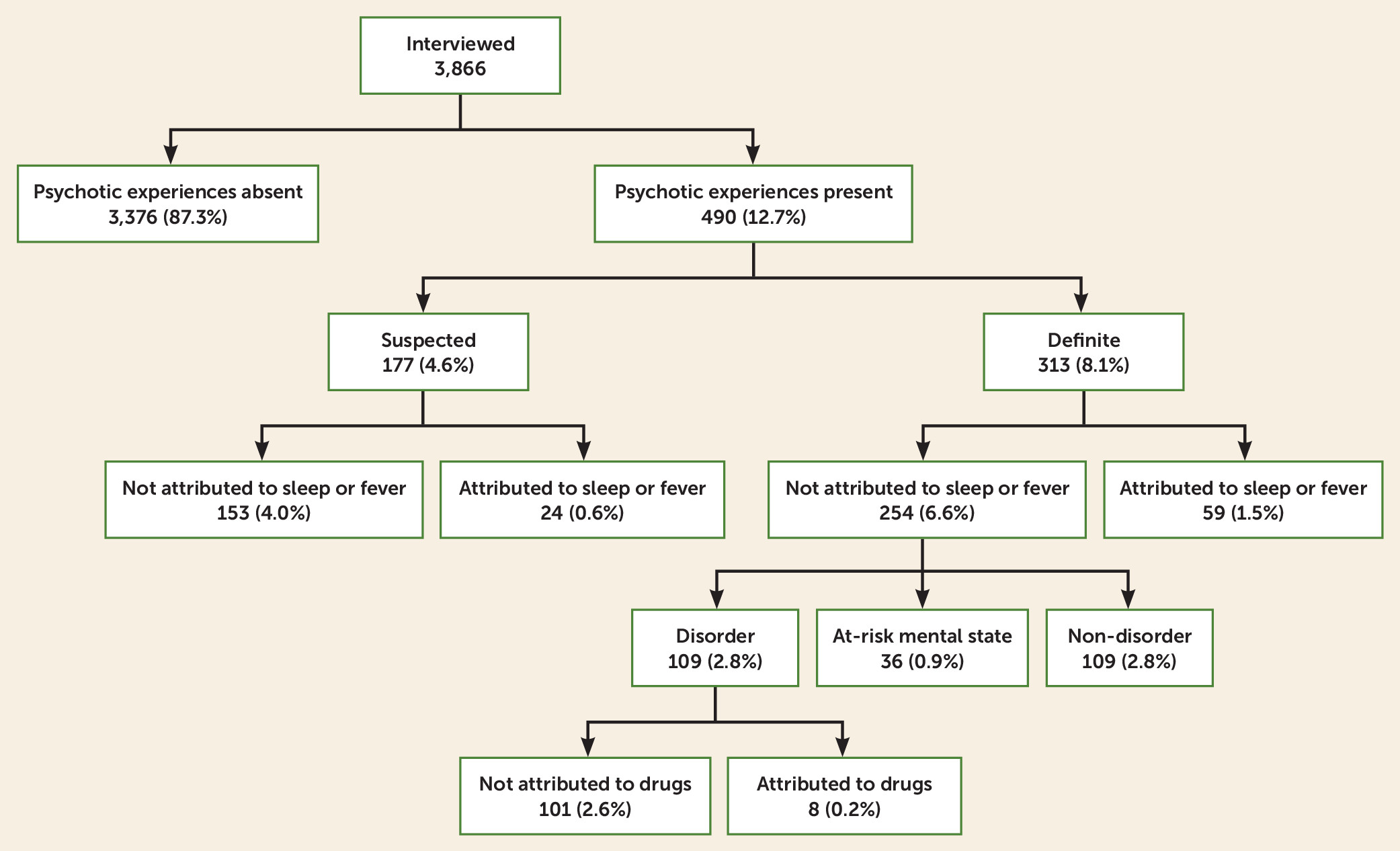

Frequency of Psychotic Experiences at Age 24

Of 3,866 individuals interviewed at age 24, 490 (12.7%, 95% CI=11.6, 13.8) were rated as having ever experienced a suspected (N=177, 4.6%) or definite (N=313, 8.1%) psychotic experience since age 12 (see

Figure 1 and Table S2 in the

online supplement for individual items). Of those with a definite psychotic experience, 268 (6.9% of the sample) had experienced a hallucination and 91 (2.4%) a delusion, and 46 individuals (1.2%) had experienced both.

Of those who were rated as having a psychotic experience, 43.7% described their experience as quite or very distressing. A higher proportion of those with a definite psychotic experience rated the experience as quite or very distressing (54.0%) compared with those with a suspected psychotic experience (25.4%; p≤0.001). Similarly, those with a definite psychotic experience were more likely than those with a suspected psychotic experience to describe any impaired social (27.5% compared with 10.9%, p≤0.001) or occupational (27.1% compared with 7.2%; p≤0.001) functioning and to report help-seeking from a professional source (29.4% compared with 6.2%; p≤0.001).

The prevalence of current (past 6 months) definite psychotic experiences at age 24 was 3.5% (95% CI=3.0, 4.2). This was similar to the prevalence of current definite psychotic experiences at age 18 (3.2%) but substantially less than the prevalence at age 12 (5.6%).

The risk of ever having a definite psychotic experience between ages 12 and 24, as estimated using only data from the interview at age 24 (8.1%), increased when we supplemented this information with data from the age-18 interview (9.6%), and substantially so when we further included information from the age-12 interview (13.4%). This was due, at least in part, to measurement error from inconsistent responses across time points (see Table S3 in the online supplement).

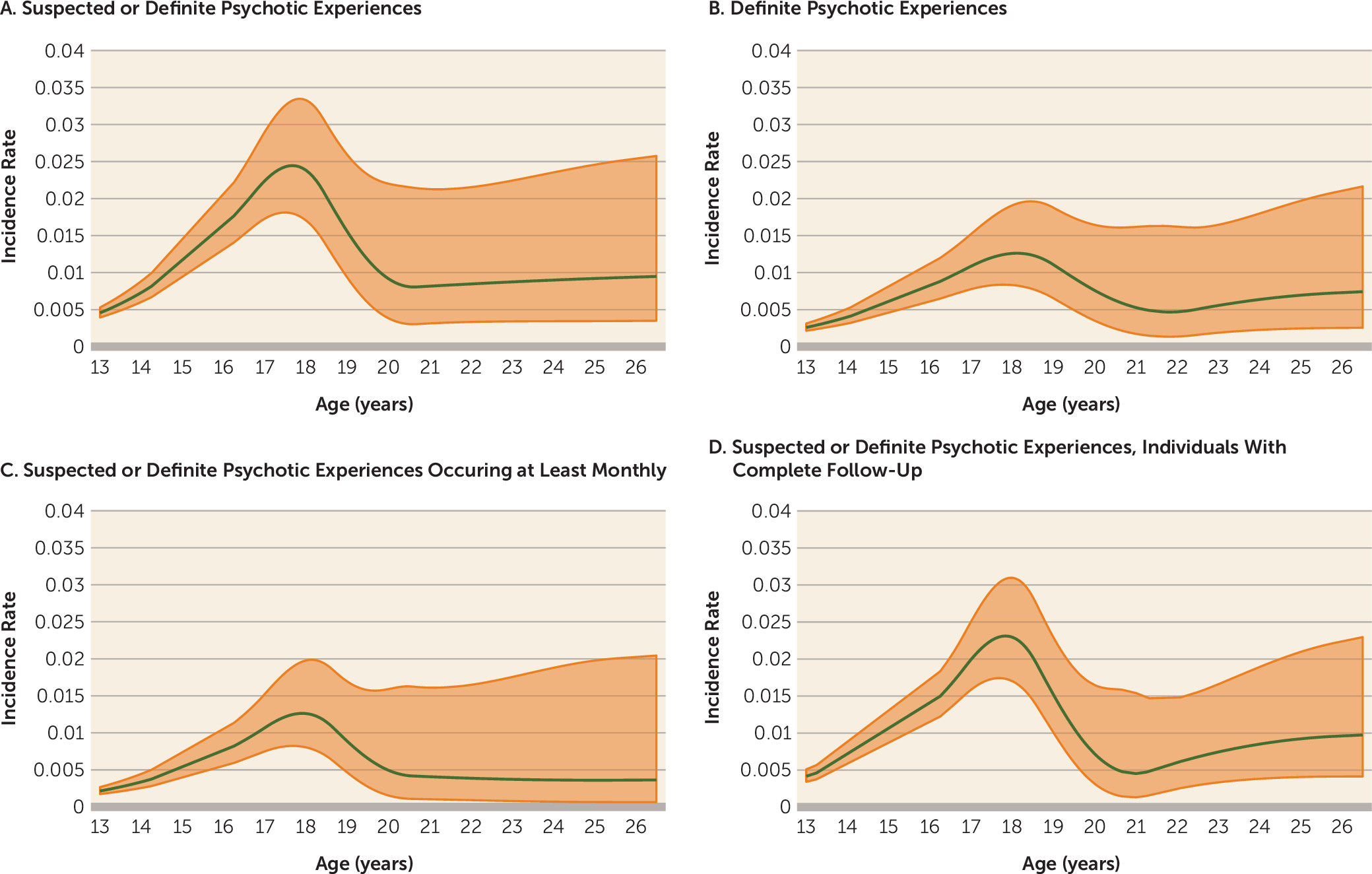

Incidence Rates

The incidence rate of the repeatedly assessed 12 psychotic experience items increased overall from early adolescence to early adulthood, with a peak around ages 17–19 (

Figure 2 and Tables S4 and S5 in the

online supplement). This pattern was similar when we restricted the analyses to definite psychotic experiences, to psychotic experiences that recurred at least monthly over a 6-month period, or to individuals with completely observed data. There was no evidence of a difference in incidence rates between males and females (see Figure S1 in the

online supplement). The overall incidence rate in our study was approximately 1.0 per 100 person-years for suspected or definite psychotic experiences and 0.6 per 100 person-years for definite psychotic experiences.

In a sensitivity analysis that included experiences rated at the age-12 interview, where age at onset was unmeasured, the pattern of rates for definite psychotic experiences remained similar, whereas that for suspected experiences was higher in childhood (see Figure S2 in the online supplement).

At-Risk Mental States for Psychosis and Psychotic Disorder

In total, 36 individuals (0.9% of the sample, 95% CI=0.7, 1.3) met either SIPS or CAARMS criteria for a current at-risk mental state at age 24. Forty-seven individuals (1.2%, 95% CI=0.9, 1.6) met our criteria for a current psychotic disorder at this age.

At the age-24 assessment, 109 individuals (2.8%) met criteria for ever having had a psychotic disorder since age 12. Of these, 38 (34.9%) had received medication prescriptions for their symptoms, and 76 (69.7%; 95% CI=60.2, 78.2) had sought professional help for their symptoms.

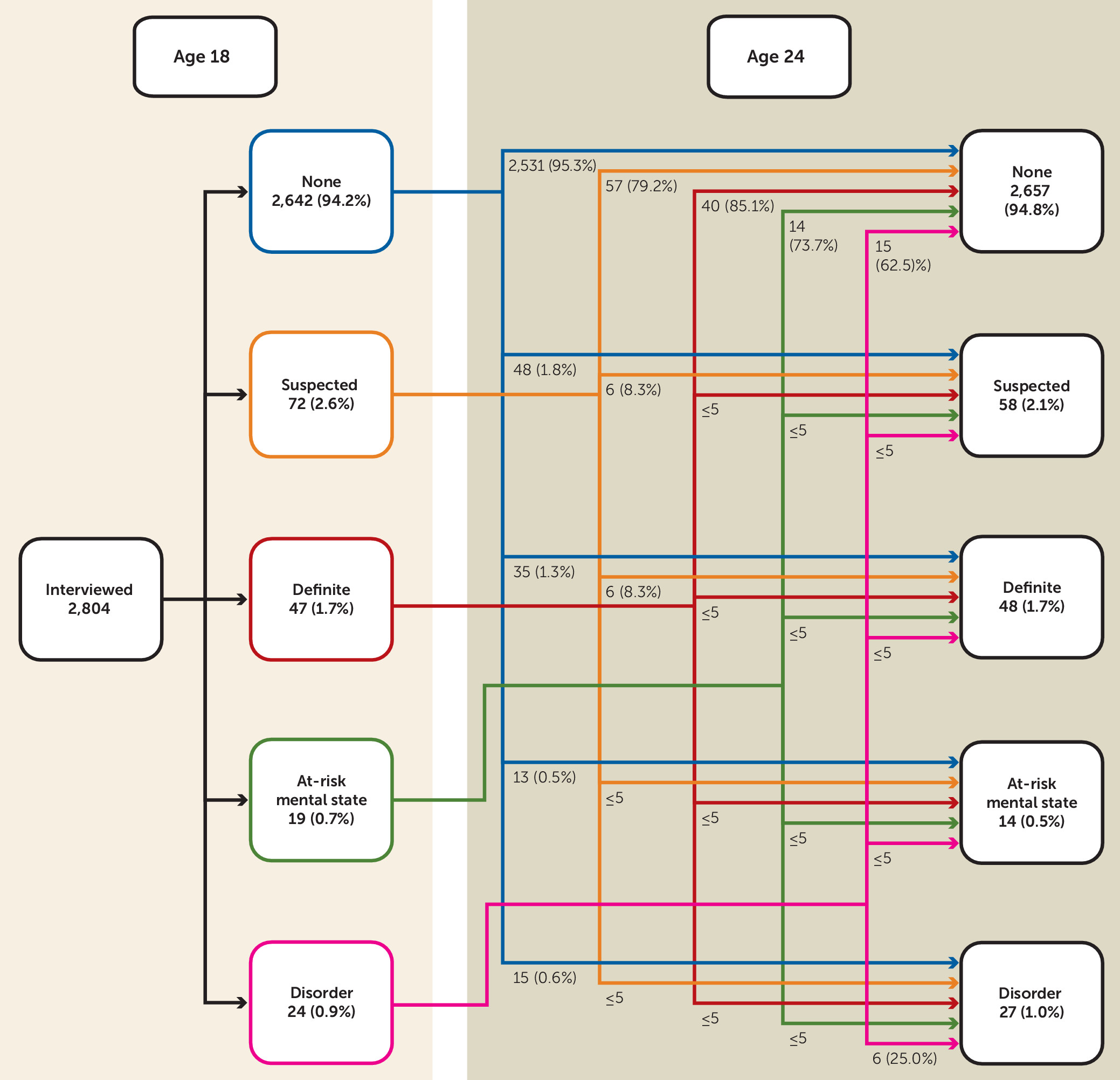

Continuity of Psychotic Experiences

A total of 2,804 individuals participated in the interviews at ages 18 and 24 (

Figure 3). Of 84 individuals with definite psychotic experiences present at age 18, 16 (19.1%) had current definite psychotic experiences at age 24 (i.e., had recurrent definite psychotic experiences over a period of approximately 6 years), and 68 (80.9%) no longer had current definite psychotic experiences at age 24 (i.e., had transient psychotic experiences over this period).

Prediction

We examined the utility of both the self-reported stem questions and the interview-rated measures of psychotic experiences at ages 12 and 18 in predicting the presence of current psychotic disorder at age 24.

As can be seen in

Tables 1 and

2, the PPV of experiences at ages 12 and 18 increased as the experiences were more stringently defined, with the poorest predictor being self-reported psychotic experiences that were not endorsed by the interviewer as being psychotic. Approximately 60% of those who met criteria for a psychotic disorder at age 24 had endorsed a “yes” or “maybe” response to the stem questions at age 12. However, only 4.8% of those rated by the interviewer as having definite, nonattributed psychotic experiences at this age met criteria for a psychotic disorder 12 years later.

The PPV for predicting psychotic disorder at age 24 was greater for interviewer ratings from the age-18 assessment compared with the age-12 assessment, with 10.0% of those rated as having nonattributed definite psychotic experiences at age 18 meeting criteria for a current psychotic disorder at age 24.

While simple “yes or maybe” responses to the stem (self-reported) items at age 18 performed more poorly than interviewer ratings for predicting psychotic disorder, their PPV was improved by addition of information on frequency and distress (

Table 1). Approximately 6% of participants who self-reported frequent or distressing experiences of hearing voices or believing they were being spied on met criteria for a psychotic disorder at age 24, and this rose to 13% for those reporting experiences that were both frequent and distressing. The corresponding estimates for interview-rated definite auditory hallucinations or delusions of being spied on were 13% and 20%, respectively.

As a result of the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, evidence of a difference in discriminative ability between interview ratings and self-report measures at age 18 for predicting psychotic disorder at age 24 (all psychotic experiences items: AUC=0.79 compared with AUC=0.75; p<0.001; auditory hallucinations and delusions of being spied on only: AUC=0.70 compared with AUC=0.68; p=0.038) was lost once information on frequency and distress was included (auditory hallucinations and delusions of being spied on: AUC=0.70 compared with AUC=0.70; p=0.868) (

Table 1).

Of 19 individuals who met criteria for an at-risk mental state at age 18, four (21.1%, 95% CI=6.1, 45.6) developed an incident psychotic disorder between ages 18 and 24, and the sensitivity was 14.3% (95% CI=4.0, 32.7).

Discussion

In this study, we conducted semistructured interviews, for the third time over a 12-year period, to assess the presence of psychotic experiences occurring from late childhood through early adulthood in a population-based birth cohort sample. While the presence of current definite psychotic experiences has remained relatively stable since late adolescence, the incidence rate of such experiences increased slightly from ages 13 to 24, with a substantial peak during late adolescence, occurring a few years earlier than the sharp rise in incidence of schizophrenia in early adulthood (

34).

The estimate of cumulative risk of psychotic experiences up to age 24 using data from multiple assessments indicates a higher occurrence of psychotic experiences than the estimate we obtained when using only the age-24 measure, and it demonstrates the importance of a repeated-measures design. Reasons for this measurement error include forgetfulness, changes in interpretation of questions with maturity, changes in valuation of social norms, and a learning bias to avoid longer assessments. Indeed, underestimates in single-time-point recall of a measure compared with multiple-time-point assessments is common (

35–

37). Such measurement error, and error in recalling age at onset of experiences, may have affected the patterns of incidence observed, although our use of repeat measures with relatively short time intervals between them will have helped minimize this error.

The transitory nature of most psychotic experiences recorded in general population samples has been well documented (

7,

9–

14), and our findings here are consistent with the literature. Nevertheless, it is germane that almost a third of individuals rated as having had definite psychotic experiences had sought professional help for them or reported impaired function because of their occurrence, indicating that as well as indexing a heightened risk of developing a psychotic disorder in the future (

4,

8,

19,

38), these experiences in themselves are often of current clinical relevance (

39,

40).

Furthermore, 30% of participants who met our criteria for a psychotic disorder had not sought professional help for their experiences, indicating a significant and important unmet public health need in adolescents and young adults in the general population.

The use of individual-level interventions to reduce the individual and population health burden of psychotic illnesses requires identification of individuals at high risk. Our study demonstrates that approximately 60% of those who met criteria for a psychotic disorder at age 24 had a self-reported psychotic experience at age 12, indicating that onset of odd or unusual experiences, even if they do not meet interviewer-rated criteria for being psychotic, are present from childhood in the majority of people who develop a psychotic disorder by their mid-20s. While the positive predictive value of such self-rated experiences was poor, it was improved by the addition of information on frequency and distress, although sensitivity was reduced. The predictive ability of these measures may well be improved by utilizing additional information on functional decline, cognitive ability, and other biomarkers of early transitioning to psychosis (

41,

42).

Structured interviews and questionnaires overestimate psychopathology compared with semistructured approaches, especially in general-population samples (

43,

44), and indeed, in our study, interviewer ratings of psychotic experiences performed better than self-report measures of psychotic experiences in predicting psychotic disorder. However, this distinction was less clear after we included measures of frequency and distress. Further studies, particularly ones that can utilize linkage to clinical health records, are required to examine whether self-report measures supplemented with information on frequency and distress are more efficient than semistructured interviews for prediction of psychotic disorder in general-population samples.

Approximately 1% of our general-population sample met criteria for an at-risk mental state for psychosis at age 24, as defined using CAARMS or SIPS criteria, compared with 0.6% at age 18 (

4). Our finding that approximately 21% of those with an at-risk mental state at age 18 transitioned to a new-onset psychotic disorder by age 24 is compatible with the estimates of transition in clinical services (

45,

46), and it is substantially greater than the transition risk of 0.9% in those not meeting at-risk criteria at age 18. Nevertheless, this means that nearly 80% of those meeting at-risk criteria did not transition over this 6-year period.

It is not known to what extent cases of first-episode psychosis can be prevented by identifying a larger pool of people with an at-risk mental state in the general population. In our population-based study, which was not sampled on help-seeking behavior, approximately 85% of participants with new-onset psychotic disorder between ages 18 and 24 did not meet criteria for an at-risk mental state at age 18.

These findings appear consistent with the observation within a clinical service in the United Kingdom that 4% of people with a first-episode psychosis in a service in South London came through the at-risk mental state route (

47). Sensitivity was similarly very low for the cutoff thresholds of frequent and/or distressing experiences for both self-reported and interviewer-rated measures at age 18. Further studies examining the trajectory of symptoms and referral pathways of people with first-episode psychosis into services are required. However, our findings suggest that targeting individuals in the general population solely on the basis of severity characteristics of psychotic or psychotic-like experiences, or on at-risk mental state criteria, while beneficial at an individual-patient level, may have little impact on rates of first-episode psychosis at the population level (

46).

Our study has a number of strengths, including use of a large and well-characterized birth cohort, semistructured interviews to assess psychotic experiences, and measures repeated at three time points from childhood through early adulthood to allow us to estimate patterns of incidence over this age period. However, the study also has some important limitations. First, while our sample is probably the largest cohort study available worldwide with this level of detailed information (with over 7,000 individuals interviewed on at least one of the three assessments), it is nevertheless relatively small for examining uncommon outcomes such as psychotic disorder. Our results therefore are often imprecisely estimated.

Second, there has been substantial attrition over time, as is common with long follow-ups. However, our estimates using multiple imputation were very similar to those from observed data, suggesting that they are unlikely to be substantially affected by selection bias, although this remains possible.

Third, while the incidence rate for psychotic experiences from age 13 onward increased overall through adolescence and early adulthood, most psychotic experiences that occurred in this cohort (928 of 1,547; 60%) were rated at the age-12 interview. Because age at first onset was not measured at this interview, our primary analysis did not model incidence rates prior to age 13. However, under specific assumptions, as shown in the online supplement, we can see that the incidence of suspected experiences may be higher before age 13, whereas the incidence of definite experiences is consistent with our primary analysis, rising from mid-childhood onward and peaking in late adolescence or early adulthood.

Finally, there may be some misclassification of at-risk mental states, as the Psychosis-Like Symptoms Interview is not wholly comparable to the SIPS or the CAARMS, and it is also possible that our definition of psychotic disorder is too broad and includes individuals who would not be classified as having a disorder in a clinical setting. However, our requirement that psychotic experiences be recurring and cause either severe distress, very impaired function, or help-seeking from a professional suggests that these individuals have a need for clinical care. Furthermore, applying more stringent criteria so that experiences need to be recurring on a weekly rather than a monthly basis, which might be more akin to the frequency level that would be seen in clinical practice, only changes our estimate of psychotic disorder at age 24 from 1.2% to 1.0%.

Although our findings must be interpreted within the context of these limitations, our study shows a peak in incidence of psychotic experiences during late adolescence, and our findings highlight an important unmet need for care in the general population of young people with a psychotic disorder. Furthermore, we demonstrate the potential utility of both self-report and semistructured assessments of psychotic experiences for prediction of psychotic disorders in the general population, but because of the low sensitivity, targeting individuals only on the basis of more severe symptom characteristics will likely have little impact on population levels of first-episode psychosis.