Mental disorders are a leading cause of ill health and disability worldwide (

1). Schizophrenia affects 2.4 million people in the United States (

2) and is associated with a 3.7-fold increased mortality risk (

3). Antipsychotics, including olanzapine, are the cornerstone of treatment of schizophrenia. In long-term effectiveness studies, olanzapine treatment was associated with lower rates of hospitalization for disease exacerbation (

4,

5), higher rates of remission (

6), and consistently longer time to all-cause discontinuation (

4,

5,

7). Despite olanzapine’s robust efficacy, the associated risk of significant weight gain and metabolic sequelae (

4,

8) has limited its overall clinical utility (

9).

A combination of olanzapine and samidorphan administered as a single tablet is under development for treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder, and it is hypothesized that the combination treatment would be associated with significantly less weight gain than olanzapine monotherapy. Antipsychotic efficacy of the combination treatment has been established in a phase 3 study in patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia (

23). In preclinical studies, coadministration of olanzapine and samidorphan was found to attenuate olanzapine-associated weight gain and mitigate several olanzapine-associated metabolic abnormalities, independently of effects on weight (

24). In a 12-week phase 2 dose-ranging study in patients with schizophrenia, combined olanzapine/samidorphan treatment resulted in a 37% reduction in weight gain compared with olanzapine (

25). Thus, combined olanzapine/samidorphan treatment may have an improved benefit-risk profile compared with olanzapine, providing an important long-term treatment option with antipsychotic efficacy and the benefit of significantly reduced weight gain (

23,

26). This 24-week phase 3 study was specifically designed to evaluate the weight profile of combined olanzapine/samidorphan compared with olanzapine at clinically relevant dosages in adults with schizophrenia.

Methods

Ethics

The study (

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02694328) was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, 1964, and Good Clinical Practice principles (International Conference on Harmonization, 1997). The study protocol and all amendments were approved by an institutional review board at each study site.

Patients

Patients 18–55 years of age meeting DSM-5 criteria for a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia were enrolled. Patients were required to be outpatients, have a baseline body mass index (BMI) between 18 and 30, and have stable body weight (self-reported change ≤5%) for at least 3 months before study initiation.

Key exclusion criteria included a history of treatment-resistant schizophrenia, <1 year elapsed since initial onset of symptoms, naive to antipsychotic medication, active alcohol or substance use disorders (excluding marijuana/tetrahydrocannabinol), or any clinically significant or unstable medical illness (e.g., diabetes, hypo- or hypertension, thyroid dysfunction, and history of seizure disorder or brain tumor) that might compromise patient safety or study endpoint assessments or interfere with the ability to fulfill study requirements. Opioid agonist use within 14 days of screening, opioid antagonist use within 60 days of screening, or anticipated need for opioid treatment during the study were exclusionary, as was the use of olanzapine in the 60 days before screening. All patients provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study.

Study Design

This was a phase 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind study conducted in the United States. Candidates were screened within 30 days of randomization; eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive treatment with either combined olanzapine/samidorphan or olanzapine for 24 weeks (see Figure S1A in the

online supplement). Study completers were eligible to enroll in a long-term open-label safety study evaluating treatment with combined olanzapine/samidorphan over 52 weeks (

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02873208); those who elected not to enroll (or who prematurely discontinued the double-blind study) entered a 4-week safety follow-up period.

Study Treatment

The daily doses of combined olanzapine/samidorphan used in this study (10 mg olanzapine/10 mg samidorphan [10/10] and 20 mg olanzapine/10 mg samidorphan [20/10]) represent the lowest and highest approved maintenance dosages of olanzapine for schizophrenia treatment and the intended therapeutic fixed dosage of samidorphan, representing the optimal weight and safety profile when combined with olanzapine (

25,

27).

In general, the use of psychotropic medications other than study drug was prohibited, except for beta-blockers, antihistamines, benzodiazepines, and anticholinergics for akathisia or extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients who were taking other antipsychotic medications at study entry were cross-tapered off these medications and titrated onto either combined olanzapine/samidorphan treatment or olanzapine monotherapy over the course of 2 weeks. In the first week, patients received daily doses of combined olanzapine/samidorphan 10/10 or 10 mg olanzapine. The olanzapine dosage was increased to 20 mg/day beginning at week 2. At the end of week 2, 3, or 4, the olanzapine dosage could be lowered to 10 mg/day for tolerability reasons. No dosage adjustments were permitted beyond week 4.

Assessments

Patient visits occurred weekly through week 6, then biweekly for the remaining 18 weeks. Assessments included body weight and waist circumference (both measured in triplicate), vital signs, ECG, adverse events, extrapyramidal symptoms (Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale [AIMS] [

28], Simpson-Angus Scale [

29], Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale [

30]), the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (

31), the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (

32), and the Clinical Global Impressions severity scale (CGI-S) (

33). Blood samples for fasting (≥8 hours by self-report) metabolic laboratory parameters (triglycerides, cholesterol, glucose, and insulin) and nonfasting hemoglobin A1c were collected.

Primary and Secondary Endpoints

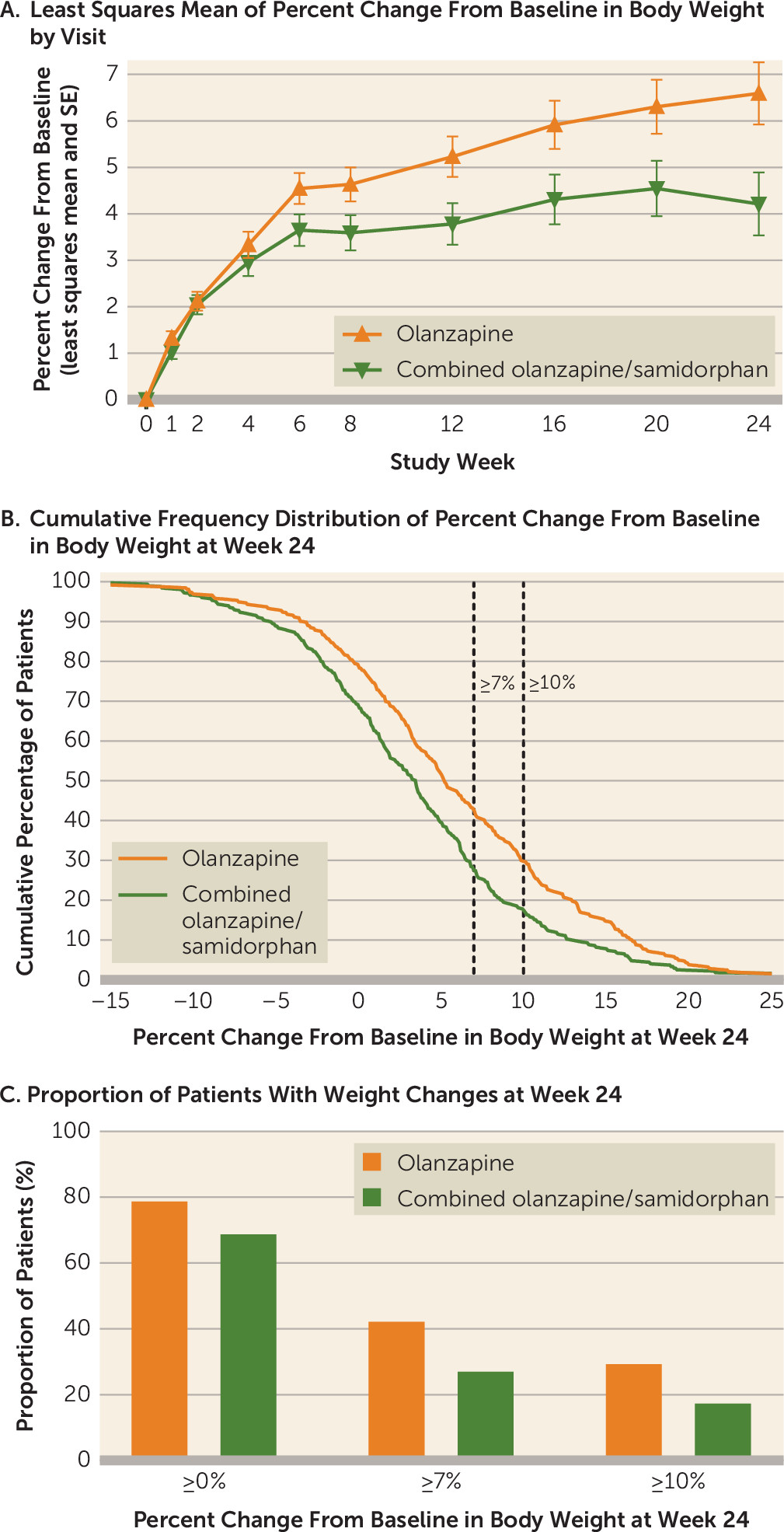

The co–primary endpoints were percent change from baseline at week 24 in body weight and the proportion of patients with ≥10% weight gain from baseline at week 24. The key secondary endpoint was proportion of patients with ≥7% weight gain at week 24. The cutoffs of 10% and 7% were selected on the basis of commonly accepted thresholds of clinically significant changes in weight for weight management and psychiatric treatments, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

The initial target sample size was 200 patients per treatment group. This sample size was estimated to provide ≥90% power to detect significant differences in mean percent change in body weight of 4% (SD=9%) and in the proportion of patients with ≥10% weight gain of 13% at week 24, assuming a cumulative dropout rate of 40%. A prespecified unblinded interim analysis for sample size reestimation was conducted by an independent statistical center when 50% of patients completed the double-blind treatment period or discontinued. Because the conditional power of the co–primary endpoints was less than 90% based on the interim results, the sample size was subsequently increased to 540 patients.

Safety was assessed in patients who received at least one dose of study drug. Weight and antipsychotic efficacy were assessed in all patients who had at least one postbaseline weight assessment.

To control for multiplicity, both co–primary endpoints were tested at an alpha of 0.05 based on the method described by Cui et al. to adjust for the unblinded interim analysis (

34). The key secondary endpoint would be tested only if both co–primary endpoints were met.

Missing weight assessments were imputed by multiple imputation sequentially for each visit, using a regression method. The imputation regression model included treatment, race, and baseline age group as factors and body weight at all previous visits (including baseline) as covariates. Five hundred imputations were carried out. The co–primary endpoint of percent change from baseline in body weight at week 24 was analyzed by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) based on the imputed data sets. The ANCOVA model included treatment, race, and age group as factors and baseline weight as a covariate. Results were combined using Rubin’s method. Additional details are provided in the online supplement.

Analysis of the other co–primary endpoint and the key secondary endpoint (proportion of patients with ≥10% and ≥7% weight gain at week 24, respectively) was carried out using a logistic regression model based on the same multiply imputed weight data as the percent change from baseline in body weight at week 24.

Analyses of change from baseline in body weight and waist circumference at each visit were similar to those of the co–primary endpoint of percent change in body weight at week 24. Change from baseline in metabolic laboratory parameters, PANSS score, and CGI-S score were analyzed using a mixed model with repeated measures; the model included treatment, visit, treatment-by-visit interaction, race, and age group as categorical fixed effects and baseline weight as a covariate, with an unstructured covariance structure and Kenward-Roger approximation to adjust the denominator degree of freedom.

Discussion

In this 24-week study in patients with schizophrenia, treatment with combined olanzapine/samidorphan resulted in significantly less weight gain compared with olanzapine monotherapy. Differences in weight gain were apparent at week 6 and remained lower in the combined olanzapine/samidorphan group at each subsequent visit through week 24. The weight distribution profile in the combined olanzapine/samidorphan group was shifted compared with the olanzapine group, such that fewer patients gained weight across a range of cutoffs. Not only were patients less likely to gain any weight with combined olanzapine/samidorphan, but also the risk of clinically significant weight gain (of ≥7% and of ≥10%) was reduced by 50% relative to olanzapine.

The results of this study extend those of a previous study in which combined olanzapine/samidorphan treatment was associated with significantly less weight gain compared with olanzapine over 12 weeks (

25). In both studies, combined olanzapine/samidorphan treatment resulted in weight gain over the first 4 to 6 weeks before stabilizing. The mean increase in weight in this study was 3.18 kg in the combined olanzapine/samidorphan group and 5.08 kg in the olanzapine group at 24 weeks. Some degree of weight gain is commonly reported in clinical trials with other atypical antipsychotics during periods beyond 6 months. For example, weight increases with brexpiprazole (1.3 kg) (

36), cariprazine (1.7 kg) (

37), quetiapine (2.4–3.7 kg) (

38,

39), and risperidone (4.3 kg) (

40) have been reported. Comparisons to other antipsychotics must be interpreted cautiously owing to different study objectives, designs, populations, and analyses. Nonetheless, the data suggest that while combined olanzapine/samidorphan may be associated with more weight gain than some atypical antipsychotics, it may be within the range of weight gain seen in commonly used treatments, such as risperidone and quetiapine.

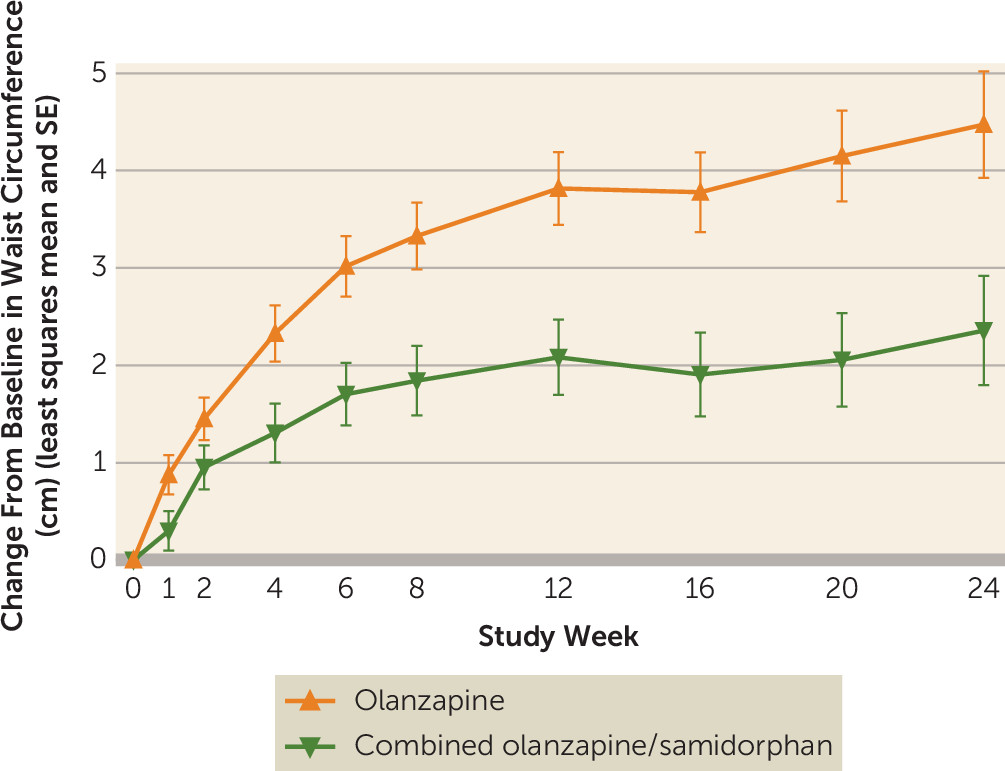

In addition to less weight gain, combined olanzapine/samidorphan was also associated with significantly smaller increases in waist circumference compared with olanzapine. Waist circumference is a proxy for central fat accumulation (

41), and increases in waist circumference have been associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, even independently of weight (

41,

42). The separation in waist circumference for combined olanzapine/samidorphan versus olanzapine occurred earlier than the separation in weight, suggesting that while weight gain was similar during the first 6 weeks, it may have been distributed differently. A shift away from increasing abdominal adiposity may potentially lead to a reduction of cardiovascular and diabetes risk with combined olanzapine/samidorphan in comparison to olanzapine, especially long-term. For patients treated with combined olanzapine/samidorphan, the risk of having a waist circumference increase of ≥5 cm was reduced by approximately 50% compared with olanzapine. A 5-cm increase in waist circumference is clinically relevant, as it not only represents a change in pant size for the average adult but also is associated with an increased mortality risk (9% in women and 7% in men) (

35).

A notable finding in this study was that there were no differences between combined olanzapine/samidorphan and olanzapine on the metabolic laboratory parameters assessed, despite differences in weight gain and waist circumference increase. Changes in fasting lipid and glycemic parameters with olanzapine treatment were generally small at 24 weeks, limiting the ability to detect differences with combined olanzapine/samidorphan. The lack of a more pronounced metabolic effect with olanzapine seems to be at odds with the increased risk of diabetes and dyslipidemia associated with olanzapine treatment in clinical practice (

43,

44). While the changes in fasting lipid and glycemic parameters observed over 24 weeks in this study were consistent with what has been reported for olanzapine in some studies of similar duration (

38,

45–

47), generally a higher risk of cardiometabolic adverse effects would be expected with olanzapine (

48–

50). While weight gain is consistently observed with olanzapine across studies, metabolic effects are more variable. This variability may be related to differences in study designs, patient populations, and analysis methods, making it difficult to generalize across studies. Finally, as this study did not directly compare combined olanzapine/samidorphan with non-olanzapine antipsychotics in similar populations, the overall metabolic risk relative to these medications is unclear. Additional studies designed to evaluate the comparative metabolic risk of combined olanzapine/samidorphan and various other antipsychotics are warranted.

Notably, the timing of changes in metabolic laboratory parameters was an important factor in this study. For both treatments, changes in metabolic laboratory parameters generally occurred early, within the first few weeks, with little additional change over the remainder of the treatment period. The continued weight increases observed with olanzapine did not translate to any clear metabolic worsening beyond these initial effects. As a result, mitigation of weight gain by combined olanzapine/samidorphan did not lead to a discernible metabolic benefit in this study. This finding points to a potential pitfall in trying to relate olanzapine-associated metabolic changes solely to changes in body weight. Several studies have documented the effects of olanzapine on lipid and glucose metabolism within days of initiating treatment (

51–

53). These early metabolic effects appear to be more directly related to the drug itself rather than to secondary consequences of weight gain. The time frame over which these initial changes persist or give way to the longer-term secondary changes associated with accumulating weight is not well understood. The 6-month duration of this study may have been insufficient to detect these secondary weight-related changes in metabolic risk factors; thus, any potential metabolic effects derived from mitigating weight gain with combined olanzapine/samidorphan may have been missed.

While a metabolic benefit for combined olanzapine/samidorphan relative to olanzapine was not observed in this study, extensive evidence supports the expectation that mitigation of olanzapine-associated weight gain should ultimately lead to metabolic benefit. Olanzapine-associated weight gain poses such a relevant safety risk because it continues over long-term treatment, with a majority of patients gaining substantial amounts of weight over periods well exceeding the 6-month time frame of this study (

27,

54,

55). In 293 patients treated with olanzapine for a median of 2.5 to 3 years, 22% gained 10–20 kg, and 9% gained more than 20 kg (

54). Epidemiologic evidence suggests that gaining as little as 5 kg can result in an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and this risk escalates further with weight gain of more than 20 kg (

56). Similarly, the risk of cardiovascular mortality increases exponentially as patients transition from being overweight to obese (

57). Obesity is also associated with numerous other health complications, including asthma, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, and chronic back pain (

58). By stabilizing weight after the initial 4 to 6 weeks of treatment and shifting the weight gain distribution so that fewer patients gain substantial amounts of weight, combined olanzapine/samidorphan will likely have a noticeable health benefit relative to olanzapine over time. Moreover, as mentioned above, a metabolic benefit may also be afforded by reduced central fat accumulation compared with olanzapine. Ongoing safety studies (

ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02873208, NCT02669758, NCT03201757) are assessing the long-term effects of combined olanzapine/samidorphan on weight and metabolic laboratory parameters, and results will further inform the relative cardiometabolic effects of this drug combination.

There are currently no treatments approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to address antipsychotic-associated weight gain (

11). Several approaches have been explored, including adjunctive metformin and switching to or supplementing treatment with an antipsychotic with a lower weight-gain liability (e.g., aripiprazole) (

59). Metformin is one of the most well-studied approaches (

60,

61). Many of the metformin studies investigated reversal of olanzapine or other antipsychotic-associated weight gain rather than prevention (as in the present study), although there are some studies in which prevention was assessed. While metformin has the potential to reverse and even prevent olanzapine-associated weight gain (

62–

67), these results must be interpreted cautiously, given the variability in effects and effect sizes, small sample sizes (typically fewer than 100 patients total), and short assessment periods (several studies had durations shorter than 24 weeks). Moreover, study designs varied widely (e.g., inpatient versus outpatient, early-episode patients versus patients with established disease, and inclusion of only Chinese populations or of lifestyle modifications, such as calorie restrictions and exercise programs). Of note, the present study explicitly discouraged changes in lifestyle to more accurately focus on weight differences due to treatment. While adjunctive lifestyle approaches may prove useful in limiting olanzapine-associated weight gain (

68), combined olanzapine/samidorphan is intended to be taken as a single tablet that provides the antipsychotic effect of olanzapine with significantly less associated weight gain.

In this study, treatment with combined olanzapine/samidorphan and with olanzapine resulted in similar improvements in symptoms of schizophrenia as reflected in PANSS and CGI-S scores. Also, combined olanzapine/samidorphan was generally well tolerated, with a safety profile consistent with that of olanzapine.

The exact mechanism of action of combined olanzapine/samidorphan is unknown. Data from preclinical animal models suggest that olanzapine induces weight and metabolic changes, and that samidorphan attenuates olanzapine-associated changes in fat mass via blockade of adipose glucose uptake and/or by preventing olanzapine-induced insulin resistance. Importantly, these effects occurred in the absence of increased food consumption or altered eating behaviors. We refer the reader to Cunningham and colleagues’ recent publication of these data (

24). However, this remains an area of active research, as many aspects of the mechanism of action of combined olanzapine/samidorphan are not understood.

Several limitations of this study may have affected the results. First, almost 40% of patients discontinued the study early, leading to a relatively high volume of missing data. This discontinuation rate is consistent with discontinuation rates reported in other 6-month studies of antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia (

45,

69). Here, the multiple imputation approach to handling missing data was appropriate and was supported by the results of the sensitivity analyses. Additional study limitations included fasting status based solely on self-report, without independent confirmation (i.e., samples may not have been truly fasting in all cases). Moreover, the restrictive BMI criterion for study entry (a BMI in the range of 18–30) in patients with long illness and antipsychotic treatment histories (mean age, approximately 40 years; most frequent prior antipsychotics, risperidone and quetiapine) may have inadvertently selected patients who were relatively resistant to antipsychotic-associated weight gain and metabolic dysregulation. Also, patients older than 55 years were excluded from the study. Ongoing studies will provide additional data on the weight and metabolic effects of combined olanzapine/samidorphan in patients with minimal prior antipsychotic exposure (

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03187769) and patients continuing treatment over several years (

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03201757).

Given the complexity and heterogeneity of schizophrenia, there is no single treatment that will work for every patient over the entire course of illness. Patients and clinicians need more treatment options to effectively manage symptoms while limiting side effect burden (

70). Combined olanzapine/samidorphan provides a potential new treatment option that possesses the antipsychotic efficacy of olanzapine with significantly less weight gain. Initial weight gain has still been observed with combined olanzapine/samidorphan over the first 4 to 6 weeks, and this must be factored into any benefit-risk assessment. However, by mitigating weight gain after this initial period and reducing the number of patients who have substantial increases in weight and waist circumference, combined olanzapine/samidorphan mitigates one of the key safety risks of olanzapine that has limited its clinical use.

In conclusion, combined olanzapine/samidorphan was found to mitigate the important side effect of olanzapine-associated weight gain while maintaining the established antipsychotic efficacy of olanzapine. While the metabolic changes observed at week 24 were similar between treatments, treatment with combined olanzapine/samidorphan resulted in a clinically meaningful mitigation of weight gain and increases in waist circumference, two well-established risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Thus, combined olanzapine/samidorphan represents a potential new treatment option for patients.