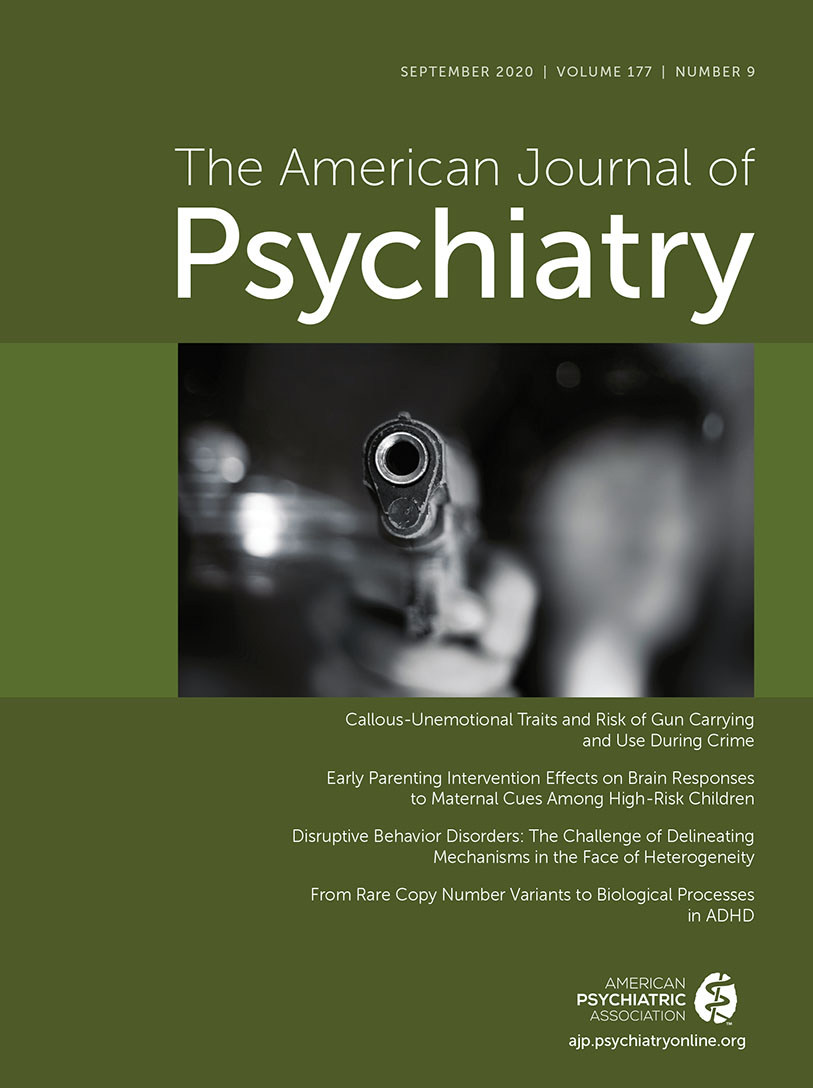

Gun violence is a serious public health concern, particularly in the United States, which has a gun homicide rate that is 25 times higher than the average respective rates of other comparable affluent nations (

1). Notably, these gun homicides are disproportionately committed by adolescents and young adults between the ages of 12 and 24 years, making the understanding and reduction of youth gun violence a critical concern. There are a number of variables known to be associated with adolescent gun use, including, but not limited to, peer gun carrying, IQ, parental supervision, violence exposure, and neighborhood dysfunction. Variables that have received very little attention in this regard, despite their considerable utility in understanding youth antisocial behavior more generally, are callous-unemotional traits (

2). Callous-unemotional traits are defined by reduced guilt, empathic concern, and displays of appropriate emotion (

2). Work on these traits, with respect to prognosis and neurobiology, led to their inclusion in DSM-5 as a specifier for conduct disorder labeled “with limited prosocial emotions.” The article by Robertson and colleagues (

3), published in this issue of the

Journal, focuses on the associations between gun use and gun carrying and callous-unemotional traits. In their study, Robertson and colleagues indexed, via self-report, callous-unemotional traits, gun ownership, and peer gun carrying at first arrest in 1,215 male juvenile offenders and then gun carrying and gun use in a crime every 6 months for 36 months (and once more at 48 months). The authors report that callous-unemotional traits predict both the frequency of gun carrying at first arrest and the use of a gun during the commission of a serious crime in the 48 months after first arrest. Specifically, every one-point increase in callous-unemotional traits was associated with a 7.6% increase in the likelihood of carrying a gun and a 6.9% increase in the probability of using a gun during a violent crime, after accounting for other predictive variables. In addition, the study demonstrates that callous-unemotional traits moderate the relationship between peer gun carrying and participant gun carrying. While peer gun carrying is positively associated with participant gun carrying in participants with low to medium levels of callous-unemotional traits, this association is nonsignificant in individuals with high levels of callous-unemotional traits.

The article is important for a number of reasons. First, it stresses the importance of individual difference variables and psychiatry for debate and policy on gun violence. The relevance of neuroscience and psychiatry is not limited to understanding incidences of mass shootings. Rather, the relevance is there for the large number of daily gun violence incidences that are committed by individuals with elevated callous-unemotional traits. Of course, the importance of considering callous-unemotional traits specifically should not be overstated. The United States does not have a gun homicide rate that is 25 times higher than the average respective rates of other comparable affluent nations because of 25 times higher levels of callous-unemotional traits. There are a number of social and environmental variables, not least ease of access, that contribute to this considerably elevated gun homicide rate. But at the same time, an understanding of individual difference variables, and particularly callous-unemotional traits, is going to be important to address the issue fully.

Second, the article further reinforces the importance of understanding callous-unemotional traits. These traits are associated with a distinct neurobiology (

4) and are associated with a variety of indications of a particularly poor prognosis for, and a severe form of, conduct disorder (

2). This article adds gun use, a form of violence particularly likely to have very severe health consequences for the victim, to this list. As noted, callous-unemotional traits are defined by a lack of guilt and empathy. The individual with these traits is less likely to be inhibited from acting aggressively, including using a gun, by the typical aversive emotional reaction that healthy individuals typically experience when thinking about or engaging in actions that hurt other individuals (

4). Indeed, the article further motivates efforts to develop effective treatments for callous-unemotional traits. Although there is some debate, adolescents with callous-unemotional traits are typically viewed as less responsive to current interventions than youths with conduct problems without callous-unemotional traits (

5). This likely reflects the distinct neurobiology associated with callous-unemotional traits (

4). The interventions that reduce conduct problems are not targeted for this specific neurobiology and thus are less effective in helping the patient in the long term. This brings us to the third important implication of the Robertson study.

Peer gun carrying has been shown to be one of the strongest predictors of adolescent gun use (

6). However, the data from the Robertson et al. article show that this predictor is significant only for those individuals with low to medium levels of callous-unemotional traits. The predictor was no longer significant for those with relatively high levels of callous-unemotional traits. These data are important for two reasons. First, they reinforce the distinctiveness of callous-unemotional traits. Something about the pathology of callous-unemotional traits interferes with the effect of peer gun carrying on the individual’s behavior. Second, the data focus on a feature of callous-unemotional traits that has been relatively ignored in the literature on these traits: atypical social affiliation (

7). Individuals with callous-unemotional traits show reduced bonding with others and, on the basis of the data here, are influenced in their behavioral choices less by the actions of others. There has been reference to a lack of attachment to significant others and some implication of atypical social affiliation generally in even some of the earliest conceptualizations of callous-unemotional traits (

8). However, any detailed understanding of this atypical social affiliation has been lacking. There are now researchers focusing on the issue (

7). The data from the Robertson et al. study reinforce the importance of such work. It is likely that if this issue fails to be understood, any intervention designed for the reduction of callous-unemotional traits will still fall short of full efficacy.

In conclusion, this important article stresses the relevance of social variables and individual difference variables when understanding gun violence. Interventions for reducing violence, including gun violence, need to consider the level of callous-unemotional traits shown by specific clients. They need to consider whether individuals with particularly high levels of callous-unemotional traits require either different interventions or augmentations to the current interventions offered. Models of gun violence, and analyses of gun violence data, need to consider callous-unemotional traits and perhaps other forms of neurobiology that have an effect on aggression, such as those underpinning irritability and response control difficulties (

4). Of course, a focus on the individual is only part of the solution to reducing gun violence. Cross-country differences in gun violence are not products of individual differences. But, echoing earlier work indicating that the most persistent 5% of offenders commit more than 50% of all crimes (

9), considering individual differences, particularly callous-unemotional traits, is going to be part of the solution to reducing gun violence.