Over the past decade, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have advanced our understanding of alcohol use disorder (AUD) (

1). Many of these studies have relied on a categorical approach to AUD phenotypes, comparing clinically ascertained case and control subjects (e.g.,

2), but recent studies have increasingly employed a complementary approach leveraging dimensional measures of alcohol consumption and screen-based AUD symptoms in population-based cohorts (e.g.,

3–

6). Compared to clinical diagnostic phenotypes, these dimensional measures can often be administered more easily at scale via self-report questionnaires, thus accelerating genetic discovery through drastic increases in sample size. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (

7), a 10-item questionnaire that screens for drinking habits and problems by measuring aspects of alcohol use and misuse in the past year, is one such measure. A recent GWAS meta-analysis of AUD and AUDIT phenotypes identified 29 novel loci (

5), representing one of the biggest advances of AUD genetics to date (

2–

4,

6).

Notably, several studies using self-report instruments have revealed that not all aspects of alcohol involvement are interchangeable. While AUDIT can be used as a unidimensional screen (i.e., AUDIT total score), previous research has shown that AUDIT can differentiate between two related but distinct facets of AUD: alcohol consumption (sum of items 1–3, AUDIT-C), which is necessary but not sufficient for a diagnosis of AUD, and problematic consequences of alcohol consumption (sum of items 4–10, AUDIT-P), which more closely resemble the diagnostic criteria of AUD. We previously found that AUDIT-C and AUDIT-P have distinct genetic relationships with clinically defined AUD (

6) as well as other forms of psychopathology. Surprisingly, AUDIT-C was positively associated with socioeconomic variables, negatively associated with some forms of psychopathology, and only moderately positively associated with alcohol dependence, whereas AUDIT-P exhibited strong positive associations with alcohol dependence and numerous other psychiatric disorders. Although this divergence may reflect true differences between the biological mechanisms underlying alcohol consumption and problems, it may be confounded by other factors, such as sources of selection bias, genetic heterogeneity among the individual items, and measurement error (

1,

8).

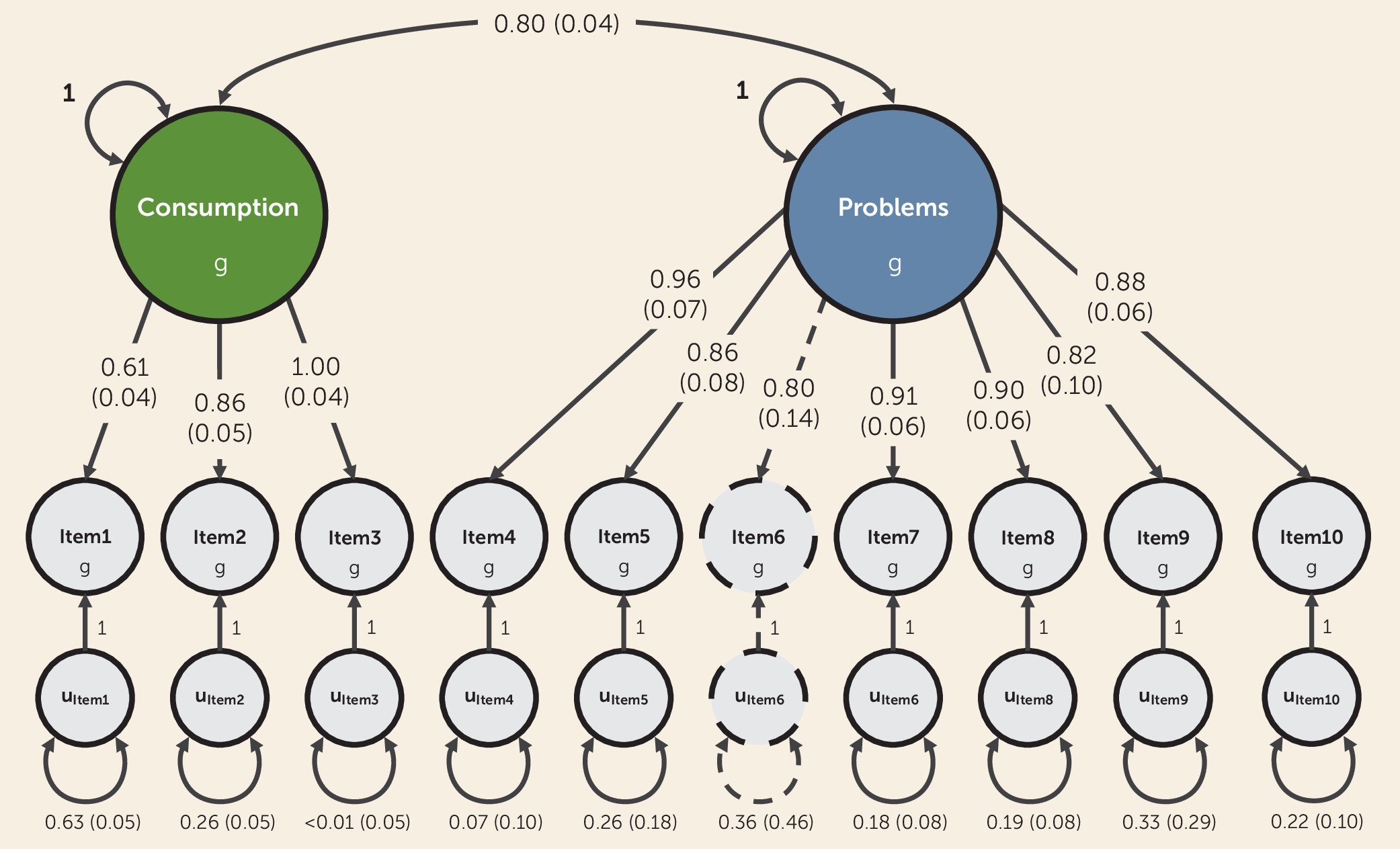

In the present study, we sought to elucidate the genetics of alcohol consumption and problematic consequences of alcohol use measured via AUDIT using genomic structural equation modeling (

9), a novel multivariate framework that allows structural equation modeling techniques to be applied to genetic covariance matrices based on GWAS results. Accordingly, we undertook the first item-level and the largest-to-date GWAS meta-analyses of AUDIT (N=160,824), using data from three population-based cohorts of European ancestry. We then used genomic structural equation modeling to analyze the item-level GWAS results with the aims of 1) investigating the latent genetic factor structure of AUDIT, based on prior knowledge (see Table S1 in the

online supplement), and 2) conducting multivariate GWASs of the resulting latent genetic factor(s). We posited that applying this approach would lead to more nuanced, empirically derived weights to each of the AUDIT items when constructing our aggregate measures (as opposed to giving each item equivalent weight), which is a novel approach for GWASs of AUD phenotypes. Finally, to characterize the biology and liability associated with each latent genetic factor, we used a variety of in silico tools and polygenic analyses spanning three independent cohorts that varied in method of ascertainment and prevalence of AUD.

We hypothesized that a higher resolution of each of the alcohol phenotypes measured in AUDIT would further our understanding of the differences among indices of alcohol consumption (items 1–3) and problematic alcohol use (items 4–10) and how they relate to health. We anticipated that the genetic contributions to alcohol consumption and problematic use would not be completely overlapping and that genomic modeling using item-level data would ameliorate the confounding issues between alcohol consumption, AUD, and indices of health that complicated previous GWAS efforts.

DISCUSSION

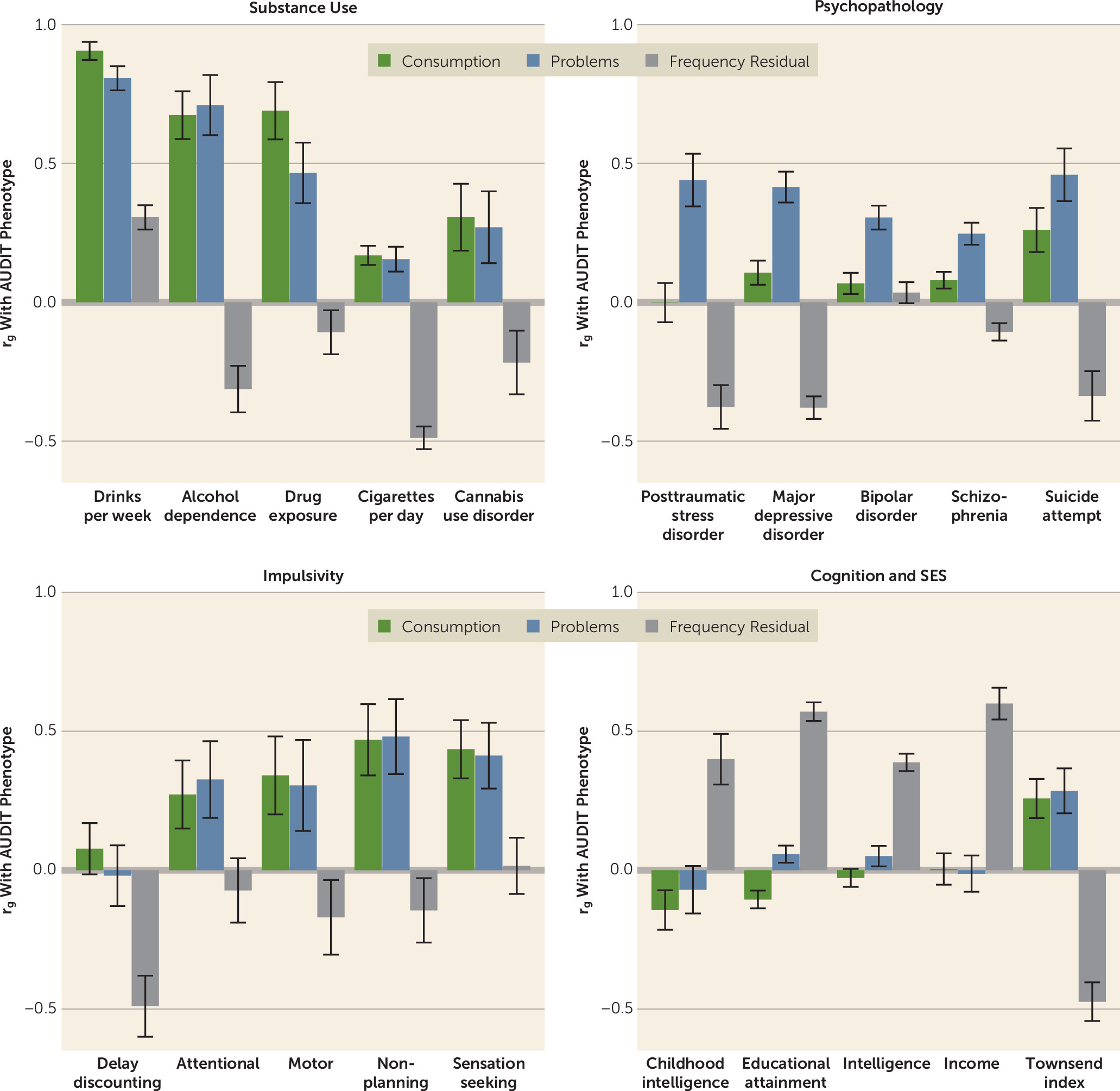

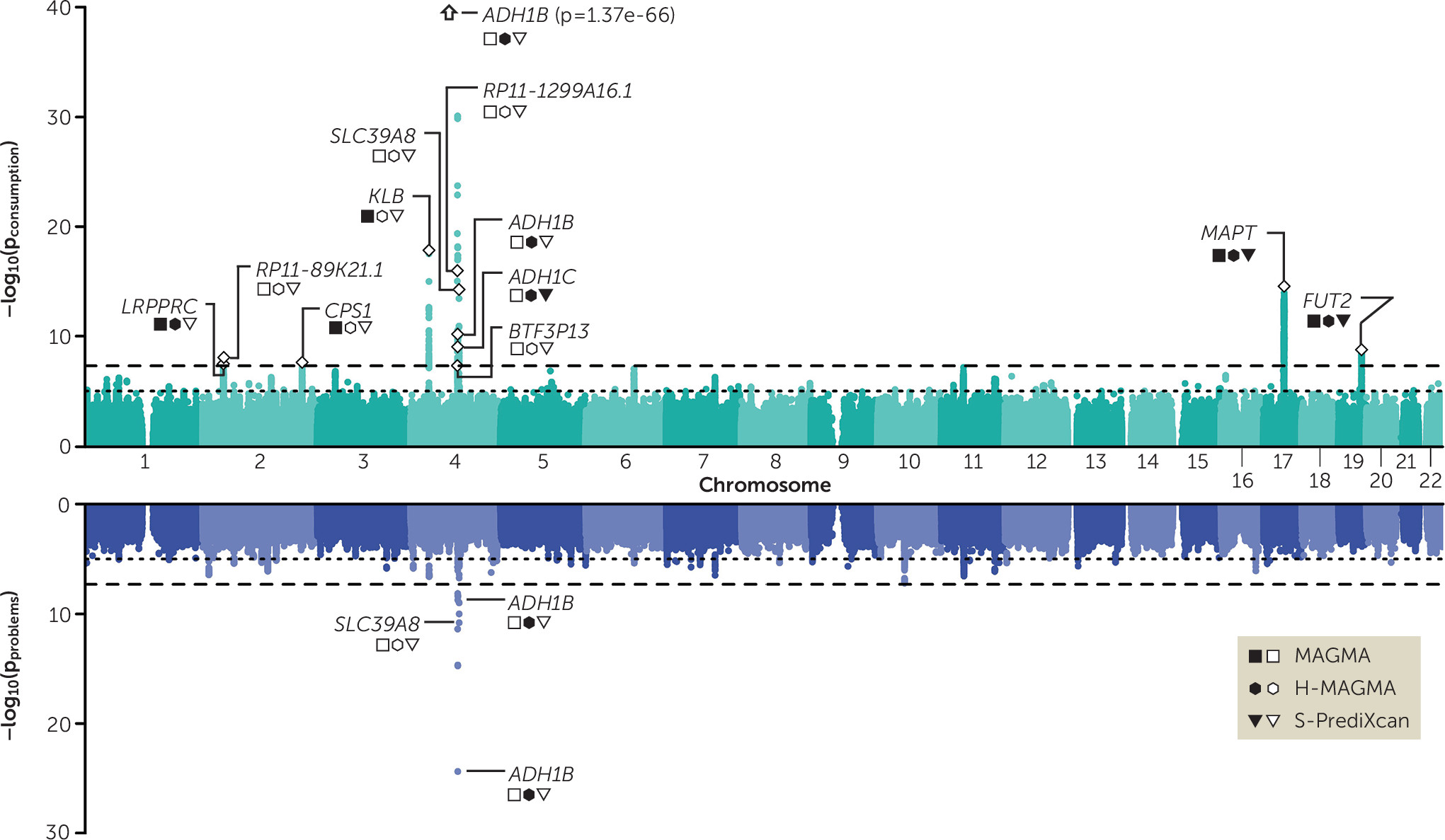

In this study, we performed the first item-level and the largest GWAS of AUDIT to date (N=160,824), and we used genomic structural equation modeling to elucidate the genetic etiology of alcohol consumption and problematic alcohol use. By conducting phenotypic and genetic factor analyses of the individual AUDIT items, we provide evidence that two correlated latent factors (consumption and problems) parsimoniously explained the covariance in measures of alcohol consumption and problematic alcohol use across both levels of analysis. Moreover, by applying empirically derived weights to the AUDIT items in a genomic structural equation modeling framework, we demonstrated that our method can ameliorate confounding biases that have complicated previous work with consumption phenotypes (in particular, the bias present in item 1). Notably, both the consumption and problems factors share a strong positive genetic correlation with alcohol dependence (both rg values ∼0.7), and we show, for the first time, that the polygenic signal of the consumption factor is strongly associated with several AUD phenotypes in three independent cohorts. Finally, the results of our bioinformatic analyses further illustrate that the consumption and problems factors have unique components of their genetic etiology. Collectively, our novel framework provides a means to study two genetic liabilities that are more closely related to AUD and advances our understanding of the associated biology in several ways, as we delineate below.

First, we built on recent investigations of the genetic etiology of AUD and related traits by analyzing each of the 10 unique items that comprise AUDIT. At this higher resolution, we were able to identify sources of genetic heterogeneity among the items, such as the consistently weaker genetic correlations between frequency of alcohol consumption (item 1) and other drinking patterns (items 2–3) and AUD symptoms (items 4–10). Our item-level approach also allowed us to empirically model the genetic relationships between AUDIT items, providing the first empirical evidence of a correlated, two-factor structure for AUD symptoms at the genetic level. In doing so, we also generated empirically derived weights to determine how individual items contribute to aggregate measures of alcohol consumption and problematic use. This is an important advance from most quantitative or dimensional genetic studies of AUD (and other forms of psychopathology), which often use composite score measures that lack statistical justification.

Second, and perhaps most importantly, we found that the consumption factor was a good genetic proxy of AUD when appropriate weights were applied to the individual items using genomic structural equation modeling. This is a striking change from previous investigations into the divergent genetic bases of alcohol consumption and problematic use, including our own prior analyses of AUDIT. GWASs of alcohol consumption phenotypes have consistently reported low to moderate overlap with AUD, which has surprised many researchers (

2–

5), and even paradoxical negative associations with a variety of diseases and disorders. Our multivariate approach has ameliorated these issues, producing an aggregate measure of alcohol consumption that is more consistent with the known patterns of alcohol phenotype associations established in the literature, such as a strong genetic correlation with alcohol dependence. Furthermore, we used genetic correlation analyses to characterize the residual genetic variance in frequency of consumption (frequency residual) that is unrelated to other AUDIT items. These analyses revealed that the frequency residual had consistently positive associations with measures of socioeconomic status and consistently negative associations with measures of substance use and psychopathology. Indeed, these genetic correlations are very similar to those observed in GWASs of AUDIT-C (

4,

5) and other GWASs of alcohol consumption (

3,

4), suggesting that single-item frequency-based measures of alcohol consumption may be particularly susceptible to confounding and/or selection bias. For example, Marees et al. (

36) reported that greater frequency of alcohol consumption was associated with higher socioeconomic status and lower risk of other psychiatric and substance use disorders in UK Biobank. In population-based cohorts with a “healthy volunteer” bias, such as the UK Biobank, the relationship between frequency of alcohol consumption and aspects of physical and mental health may not be fully generalizable (

37). This degree of bias, we speculate, will likely vary from population to population.

Third, we confirmed that the genetic contributions to alcohol consumption are partially distinct from those pertaining to problematic consequences of alcohol use. In silico analyses revealed the value of dissecting the two phenotypes, as gene- and transcriptome-based analyses identified partially divergent biological mechanisms for the consumption and problems factors. For example, the corticotropin receptor gene (

CRHR1), which has been associated with alcohol use in animals and humans (

38,

39), was associated with consumption only. As a result, we are now beginning to uncover genetic signals for aspects of alcohol involvement that have the potential to be further analyzed at the molecular, cellular, and circuit levels in cellular and animal model systems.

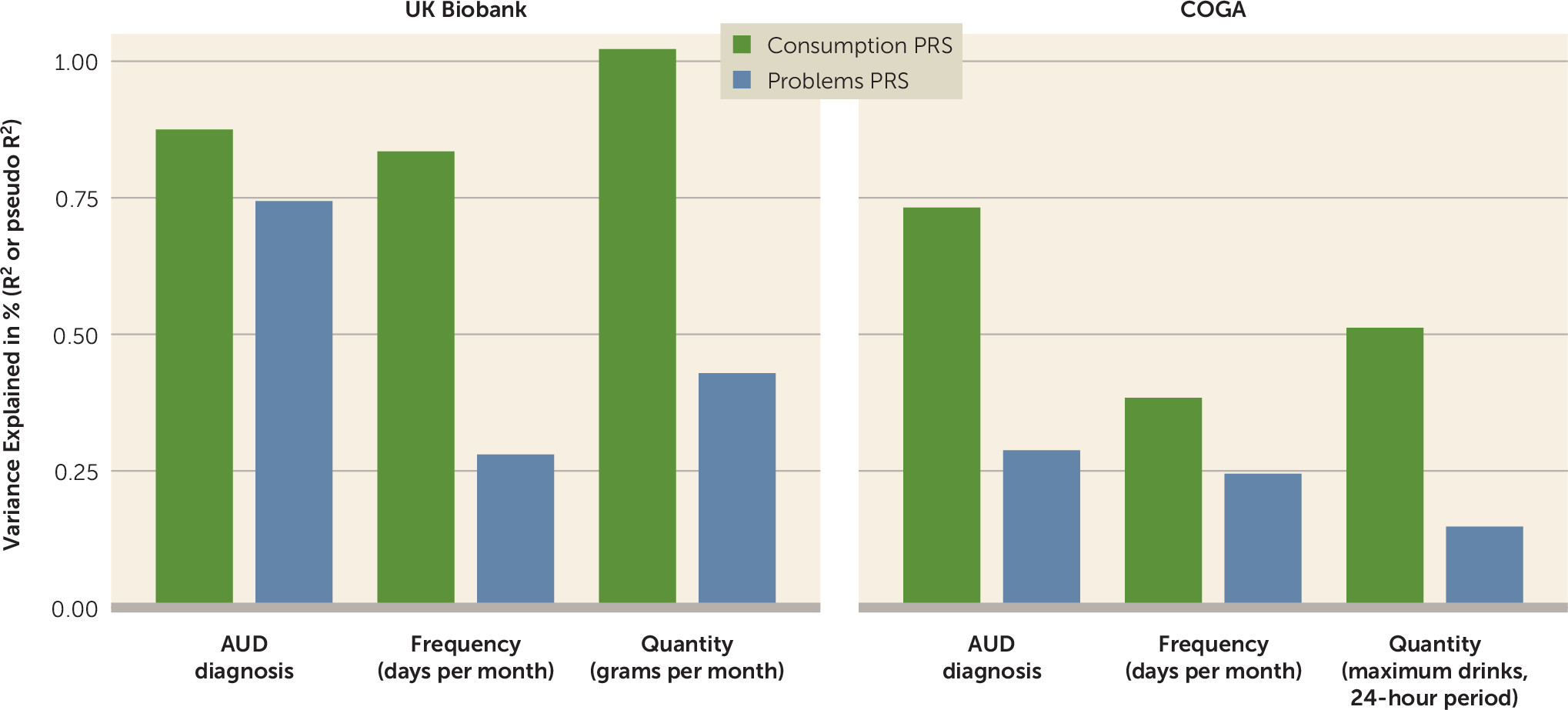

Fourth, we found that the consumption PRS was strongly associated with AUD even in higher-risk cohorts like COGA. This demonstrates the important downstream effects of allowing items to have different weights in phenotype construction. Whereas our current and previous PRSs for AUDIT-C have been disproportionately influenced by a single item (frequency of consumption) (

40), our consumption PRS was composed of the genetic effects shared among all consumption-focused items. The consumption and problems PRSs were both strongly associated with AUD in UK Biobank, even when both scores were entered in the same model. In COGA, both the consumption and problems PRSs were associated with AUD, but the consumption PRS was more strongly associated than the problems PRS. The increased influence of binge drinking (item 3), which had a large factor loading on the consumption factor, may be partially responsible for these stronger associations in a high-risk sample. However, it is perhaps more likely that these differences might be simply explained by differences in item endorsement and thus predictive power of the discovery GWASs (e.g., the consumption factor had a greater mean chi-square than the problems factor).

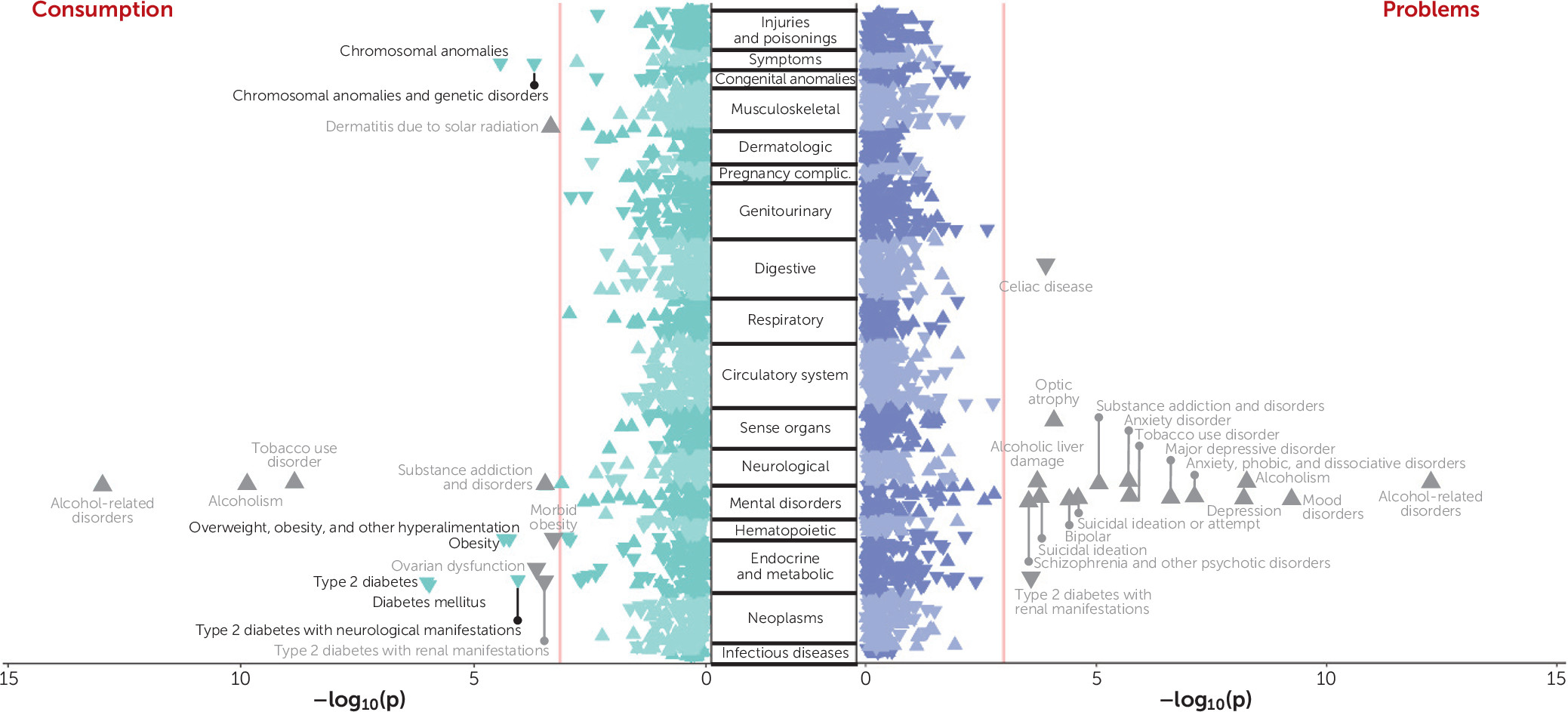

Finally, our comprehensive PheWAS analyses have linked different facets of AUD liability (via the latent factor–based consumption and problems PRSs) to a myriad of health-related outcomes in a large, independent biobank. We found that the consumption PRS was consistently negatively associated with a broad range of metabolic and congenital conditions. While it is possible that there is still residual bias in the discovery GWAS, it is important to note that this pattern of paradoxical associations with consumption is not observed in the genetic correlation analyses. Thus, it is possible that these negative associations are illustrative of selection bias or other confounding in BioVU (

41), where patients with certain conditions may elect not to drink because of unmeasured factors (e.g., family history, medical advice, contraindications for prescribed medications). Mirroring the genetic correlation results, we also found that the problems PRS was uniquely associated with numerous psychiatric disorders that are commonly reported to co-occur with AUD. However, we determined that the associations between problems PRS and mental health did not persist in the absence of the clinical manifestation of AUD. These findings suggest that the associations with mental health are not a result of horizontal pleiotropy. Instead, they may be a consequence of AUD, be correlated with other risk factors for AUD (along with and/or aside from genetic risk), or be related to ascertainment of patients with diagnosed AUD in the medical record. These results also encouragingly suggest that treating AUD could have widespread improvements in overall health.

These findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. AUDIT is a self-report measure that can be influenced by misreporting, and it only captures alcohol use in the past year, so it can be influenced by longitudinal changes in drinking that may be a consequence of, for example, other illnesses (

42). People who stopped drinking or who never drank may represent genetically distinct groups; in our data set, 4,511 individuals were never drinkers, and 4,290 were previous drinkers. While our approach has substantially reduced bias in AUDIT without excluding any individuals from discovery, future studies might consider employing multiple techniques (e.g., separate never drinkers from former drinkers) to further alleviate potential biases associated with frequency of alcohol use in population-based cohorts. Additionally, while the AUDIT PRSs tended to perform similarly in UK Biobank and COGA, the portability of PRSs can be influenced by demographic characteristics such as socioeconomic status, age, and sex (

43). It remains to be determined how generalizable the genetics of AUDIT are across different populations, especially in samples of different ancestries (as we included only individuals of European ancestry in the present study) or cultures (e.g., United Kingdom versus United States). A similar point also applies to sex-stratified samples, considering that AUDIT scores differ in men and women. Finally, it is important to note that the problems PRS exhibited weaker associations with AUD and other alcohol phenotypes in comparison to its AUDIT-P counterpart. Although the two predictors generally had similar effects in single-PRS models, the problems PRS was rendered redundant in the cross-method analyses when both of the highly correlated AUDIT-P and problems PRSs (e.g., r=0.84 in UK Biobank) were included in the regression models. However, we caution against the interpretation that the univariate GWAS approach is preferable. The multivariate GWAS function of genomic structural equation modeling is not only more flexible than traditional univariate GWAS, but its results may be more robust to confounding, as the software automatically applies a correction for population stratification (

9). Furthermore, genomic structural equation modeling is better suited to investigate nuanced genetic influences, including the possibility of identifying SNPs with heterogeneous effects across symptoms or items.

Analyzing alternative phenotypes as a complementary approach to studying clinically defined AUD, and psychiatric disorders in general, has generated considerable interest in recent years (

44). Collectively, our work demonstrates how AUDIT can inexpensively facilitate such efforts. Here, we have shown that, after correcting for some potential biases, item- or symptom-level analyses can help unpack the genetic etiology of AUD by breaking down genetic influences into specific and shared components; notably, this is possible only because we can contrast our results against gold-standard, clinically ascertained AUD GWAS data sets. While composite scores have shown some utility in previous genetic association studies, such studies often rely on strong assumptions that the scale is unidimensional and that each item is equally informative of the construct being measured. In this study, we have shown that the latter assumption is false for AUDIT. In particular, a large proportion of the genetic variance of item 1 appears to be uninformative about a broader consumption construct, as it is related to socially stratified differences in behavior rather than the alcohol phenotypes of clinical interest. Moreover, although we found a notable degree of unidimensionality among the AUDIT items, our results demonstrate that the consumption and problems factors remain distinct in their associations with health.