Suicidal behavior, which includes nonfatal suicide attempts and death by suicide, is a significant public health concern. Suicide accounts for approximately 800,000 deaths per year worldwide (

1), and nonfatal attempts are estimated to be up to 30 times more common than suicide deaths (

2). A prior attempt is one of the most prominent predictors of future death by suicide (

3,

4), and 4%−7% of individuals with a history of self-harm die by suicide in the ensuing 5–9 years (

5,

6). While suicide death is more common among men, women attempt more often (

7). Furthermore, while attempts and suicide death share many predictors (

8), there is some evidence that certain predictors are differentially associated with these two outcomes (

9). For example, suicide attempts are more common among women and youths, while deaths are more common among men and adults (

10). In addition, social isolation and anxiety disorders are associated more strongly with suicide attempts than with death (

10). Clarification of common versus distinct contributions to etiology may improve the ability to assess risk and thereby inform prevention and intervention efforts.

Previous studies have revealed familial clustering and a modest to moderate heritable component to suicidal behavior (

11–16), including recent efforts to identify specific genetic variants associated with risk (

17–

19). While many such studies have limited their analyses to one outcome (e.g., suicide death), others have collapsed manifestations of suicidality (e.g., ideation, attempt, death) into one variable using inconsistent approaches (

20–

23). Results from such studies may be driven by only one contributing measure (e.g., ideation), potentially obscuring important differences in the genetic underpinnings of different suicidal outcomes. Twin-family studies with a single outcome of interest have reported heritability estimates of 0.17–0.55 for suicide attempt (

24–

26) and 0.43 for suicide death (

27), although, as noted previously (

28), limited sample sizes contribute to widely varying heritability estimates. Some analyses have been further complicated by sample selection, precluding generalization to the overall population—for example, where participants are ascertained on the basis of a prior personal or family history of suicidal behavior (

21,

29) or a specific psychiatric disorder (

17,

23,

30). Notably, Erlangsen et al. (

31) found that adjusting for psychiatric comorbidity reduced the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) heritability (h

2 SNP) of suicide attempt from 0.05 to 0.02. Based on findings from a recent study of suicide attempt within psychiatric disorders, h

2 SNP also varies as a function of the disorder in question—for example, from 0.03 within major depressive disorder to 0.10 within schizophrenia (

17). Recent support for classifying suicidal behavior as a distinct mental disorder (

32) suggests that viewing suicidal behavior primarily through the lens of psychiatric illness has important limitations.

Efforts to directly compare the etiology of suicide attempt and death are difficult where longitudinal data on both outcomes are not available for a large, representative sample, such as when samples are selected as described above. Furthermore, the relatively low prevalence of suicide attempts and, in particular, suicide deaths has impeded efforts to obtain reliable heritability estimates for these outcomes because of inadequate statistical power. In the near term, these constraints mean that molecular genetic studies are unlikely to be able to elucidate shared versus outcome-specific aspects of etiology. Accordingly, it is necessary to employ other methodologic approaches to this important area of research.

In this study, we leveraged Swedish national registry data, including the recent addition of primary care data, to evaluate the genetic relationship between suicide attempts and death by suicide. While previous reports have employed substantial sample sizes to study familial aggregation of suicidal behavior (

11–

13), the present study is, to our knowledge, the largest to date that applies formal twin-family modeling, particularly with the goal of estimating genetic and environmental correlations between suicide attempt and death. We previously demonstrated (

33) that these outcomes should be treated independently: A liability threshold model, in which attempt and death lie on the same continuum of risk and differ only as a function of severity, does not fit the data well.

DISCUSSION

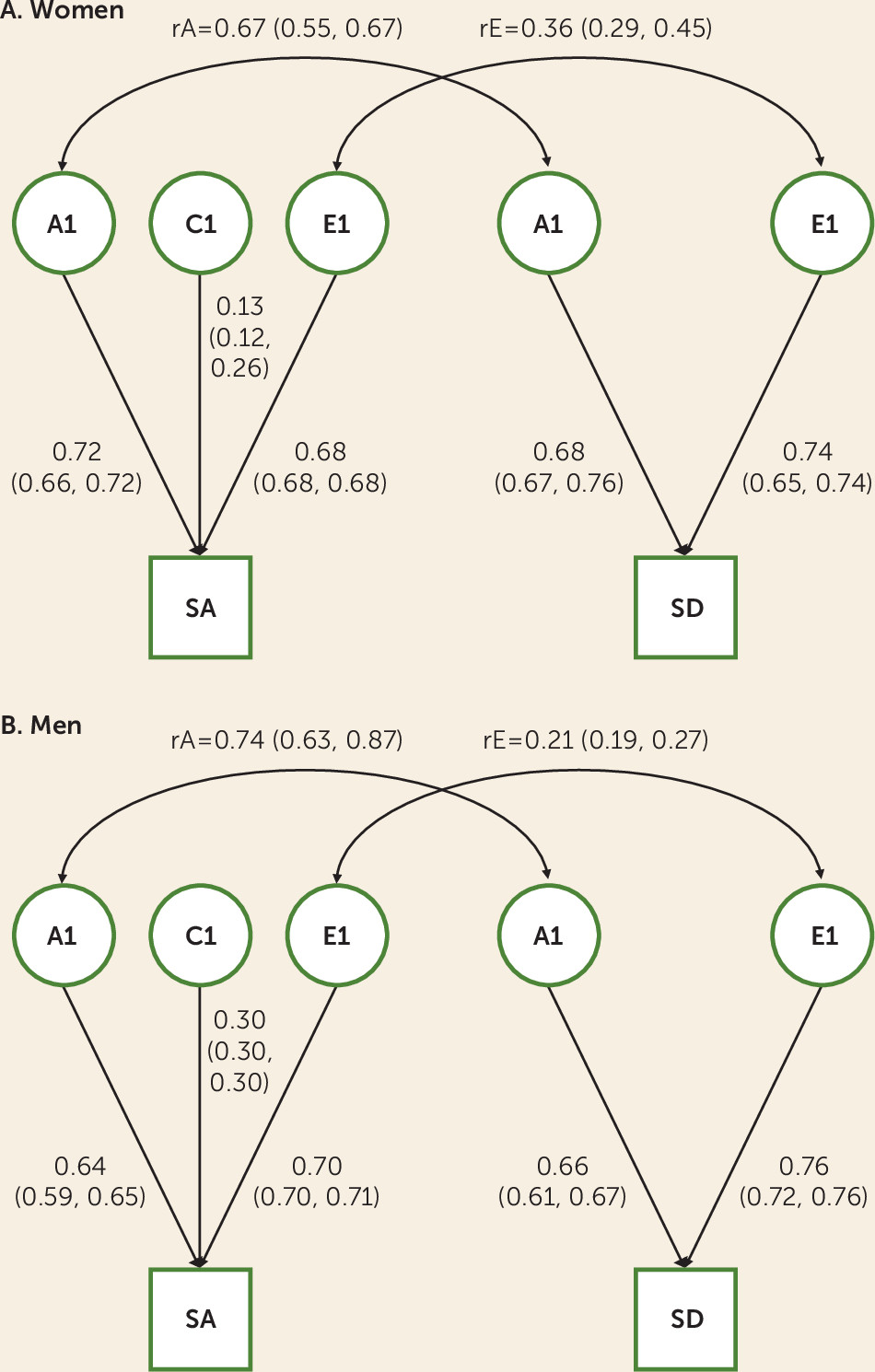

Our primary research aim in this study was to quantify the genetic relationship between suicide attempts and death by suicide using a representative national Swedish cohort. We found that attempts and suicide death were moderately heritable, with estimates from our twin-family approach (A=0.41–0.52) considerably higher than those from molecular genetic studies (h

2 SNP=0.03 for suicide attempt [

17]; h

2 SNP=0.16 for suicide death [

19]), as is common across these different methodological approaches in part because of limited sample sizes and the inclusion of only common variants in the latter (

49,

50). These outcomes are substantially genetically correlated (rA=0.67 for women and rA=0.74 for men), while the unique environmental correlation was more modest (rE=0.36 for women and rE=0.21 for men). Our findings support previous evidence that the etiologies of suicide attempt and suicide death are incompletely overlapping and may thus present distinct opportunities for prevention. In a secondary analysis, we found that the genetic factors contributing to risk of suicide attempt are potentially dynamic across the life course, underscoring the complex roles of biology and development in suicidality.

In conjunction with our previous study (

33), which found that the genetic distinction between suicide attempt and death was not merely one of severity of liability, our results have implications for studies aimed at the identification of genetic risk variants for suicidal behavior. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) that collapse attempt and death are unable to distinguish whether implicated variants or genes have outcome-specific effects or contribute to liability to both. This prevents dissection of differences in the biological etiologies of attempt and death, which may hinder prevention efforts. These complications could be extended to apply to suicidal ideation and nonsuicidal self-injury: Previous evidence suggests that these outcomes are at least partially etiologically distinct from suicide attempts and/or death (

51–

55), although a recent study revealed strong genetic and unique environmental correlations (rA=0.94 and rE=0.80) in a sample of British twins (

56). These outcomes have also been conceptualized as lying on a continuum of self-harm (

20). Recent analytic advances that decompose genetic variance into that which is common across outcomes and that which is outcome specific (

57–

59) may avoid these shortfalls once genotyped samples of sufficient size are available.

In addition, our findings underscore the relevance of evaluating family history of suicidal behaviors. Stigma about suicidal behavior persists even among family members and medical personnel (

60,

61), which may lead individuals to feel uncomfortable disclosing their own or their family members’ history. This is turn may prevent health care providers from fully appreciating patients’ risk, particularly if suicide attempts, which are more readily concealed from family members, are not disclosed. Clinicians should also be aware of both continuity of risk across the life course and the relevance of life stage–specific influences; that is, the impact of environmental exposures experienced during adolescence may persist and be augmented by exposures experienced during adulthood.

We previously reported, in an extended adoption design in Sweden, evidence for substantial environmental transmission of suicide attempt liability from parents to offspring (

33), whereas the present study found only a small contribution from the shared environment. These seemingly disparate findings are likely due in part to the different questions posed by these studies—parent-offspring “vertical” transmission of risk versus “horizontal” transmission between siblings close in age. Different, but potentially overlapping, aspects of the environment are captured across these methods. For example, the “shared environment” of the present study includes school and neighborhood-level exposures outside the home, while the “environment” of our previous study includes parenting behaviors that may differ across offspring (e.g., discipline, warmth). We have shown elsewhere (

62), using empirical estimates of twin-twin and parent-child correlations for major dimensions of parenting, that the correlation in liability among twins for typical psychiatric phenotypes due to shared parenting would range from 2% to 4%, consistent with the findings of the present study.

The modest environmental correlations between suicide attempt and death, which reflect exposures not shared by family members, indicate that extrinsic factors differentially affect risk for these outcomes. One study found that most environmental factors examined, including low income and exposure to stressful legal, interpersonal, and work-related events, increased risk for both attempts and death (

10). However, other factors had outcome-specific effects: A poor parental relationship during childhood was associated with suicide but not with serious attempts, while social isolation was associated with attempt and not death. Another study found that gun availability—that is, access to a high-lethality method—was related to suicide death but not attempt (

9); gun ownership may also be a proxy for other risk factors, such as adult antisocial behavior and exposure to violent crime (

63). The dearth of studies that examine risk factors for both suicide attempt and death within the same sample—thereby enabling direct comparisons—precludes a nuanced interpretation of the modest environmental correlations we observed. This is a critical deficit in our understanding of the etiology of these outcomes, as it affects risk prediction and prevention. Environmental exposures, in contrast to genetic variants, are potentially modifiable risk factors, but our findings reveal that environmental factors affecting risk for both suicide attempt and death represent an incomplete portrait of prevention targets.

Our secondary analysis examining suicide attempt across young people and adults addresses research questions that have not, to our knowledge, been tested previously: To what extent do genetic factors differentially contribute to risk of suicide attempt across the life course, and is there incomplete overlap of genetic factors across time? We observed that the heritability of suicide attempt was considerably higher among young people, particularly for women (confidence intervals overlapped for men across time). This raises the possibility that temperament and/or psychopathology—that is, intrinsic factors of considerable heritability—may play a more prominent role among young people than adults. In contrast, the variance in liability accounted for by unique environmental factors during adulthood suggests that adverse life experiences are more potent risk factors for suicide attempt among adults. The shared environmental correlation (rC) estimates differed markedly across sexes. These factors accounted for little of the total variance in risk (C=0.01–0.1) and the rC estimate was imprecise among women; substantive interpretation of the rC estimates is therefore not feasible.

Another key finding from the secondary analysis is the considerable sex difference in the genetic correlation between attempts among young people compared with adults (women: rA=0.79, 95% CI=0.72, 0.79; men; rA=0.39, 95% CI=0.26, 0.47). This indicates that, among women, continuity of risk across the life course is due largely to genetic factors whose impact persists across time. In contrast, for men, liability toward suicide attempt in adulthood is more strongly influenced by a qualitatively different facet of genetic influences than were relevant earlier in life. Similar to our findings on the genetic correlation between suicide attempt and death, the results of our secondary analysis have implications for gene identification studies. The higher heritability of attempts among young people may facilitate GWASs (

64) relative to studies in adults; however, restricting a GWAS study to only young people is not an ideal solution given the advantages of maximizing sample size. Instead, age at attempt could be included as a covariate along with an interaction term between age and genetic variant.

There are several limitations to these analyses. First, we were reliant on ICD codes for suicide attempts and were therefore unable to detect attempts that did not require medical attention or were not otherwise reported to a health care provider, of which there may be a considerable number (

7). Accordingly, our data likely capture more severe suicide attempts, which may be more closely related to suicide deaths than attempts overall. We were also reliant on the quality and consistency of the coding process (

65,

66). We were able to identify only one study that obtained self-reports of self-harm in a sample for which institutional records (medical registrations) were also available (

67), which found incomplete overlap between sources; however, the small sample precludes generalization to other studies. Previous evidence indicates that individuals hospitalized for self-harm may be less likely to complete a self-report survey (

67), and the rate of refusal to participate is higher for nonanonymous surveys (

68). These factors would likely lead to underestimation of suicide attempt prevalence as assessed via self-report. Such estimates vary widely—for example, from 2.7% to 14% (

68–

70). The limitations of our use of registry records may therefore be offset by the reliability of these records.

Although these findings are representative of the Swedish population, they may not be generalizable to populations in other countries. Until relatively recently, Sweden’s annual suicide rate was consistently higher than that of the United States, and it became comparable at approximately 12 per 100,000 in the period 2007–2009. Since 2010, the U.S. rate has increased while Sweden’s rate has remained stable (

71). Our secondary analyses expose potentially important shifts in the etiology of suicide attempt across the life course, including those related to environmental exposures, which may differ markedly across countries and cultures. We also note that our selection of cohort, which maximized available registry data, did not include elderly individuals.

Consistent with other studies (

40,

72), we included events of undetermined intent in our primary analyses. Our sensitivity analysis excluding those events resulted in shifts in estimates, particularly for suicide attempt among men. While some previous evidence suggests that events of undetermined intent include suicides that would otherwise be undetected (

73,

74), the conservative approach is to regard the variance component and correlation estimates from our primary and sensitivity analyses as the bounds within which the “true” estimates fall.

Our models do not account for psychiatric disorders, which are genetically related to suicidal behavior (

17). This limitation is offset by the insight provided by the present approach to the genetic and environmental influences on suicidal behavior in the general population. Indeed, the majority of those with registrations for suicide attempt (70.7%) or death (51.3%) did not have a prior registration for a major psychiatric disorder.

Although we demonstrated shifts in suicide attempt heritability, and a genetic correlation <1, across development, our analyses did not otherwise account for the potential effect of age. Given previous evidence of age, period, and cohort effects on suicidal behavior (

75–

77), additional research is warranted.