The study by Costi et al. (

1), in this issue of the

Journal, reports exciting data that a potassium anion channel modulator, ezogabine, has a significant effect on reducing depressive symptoms. The drug failed, however, to attain significance on the primary outcome, increasing ventral striatal activity, but did show significant and apparently large effects on symptoms overall, including an effect on anhedonia. There were some side effects (e.g., dizziness and headache), but these appeared manageable. The study was relatively small. On the surface, these results are potentially very important and could lead to a new class of agents with unique mechanisms of action. For all of us who treat major depression, with the relatively large numbers of subjects who demonstrate residual symptoms or frank resistance to response with antidepressant therapy, any new and well-tolerated treatment is more than welcome. The study, however, also points to a number of thorny issues regarding study design (including what should be the declared primary outcome measure), biomarker sensitivity, and results interpretation that need to be discussed as we go further with such approaches to provide likely successful pathways for drug discovery and development.

In the past two decades, we have observed a number of failures in new antidepressant drug development, with studies often failing to separate from placebo in phase III after seemingly successful separation in phase II. Similar experiences have been seen with new antipsychotics. The ultimate result has been not only a loss of dollars invested in these trials but large pharmaceutical companies fleeing development of psychiatric treatments, particularly antidepressants and antipsychotics. Many of us in the field were so concerned that over the past decade, we organized a number of meetings in the United States and in Europe to discuss what should be done (

2). These meetings were sponsored by several organizations, including the American Psychiatric Association and the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, among others. Stakeholders included those professional groups, as well as representatives from industry, venture capital funds, private foundations, the National Institutes of Health, the European Medicines Agency, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), etc. These efforts have in part led to some resurgence in drug development, much of it via new start-ups in the area, which is already bearing some fruit (

3).

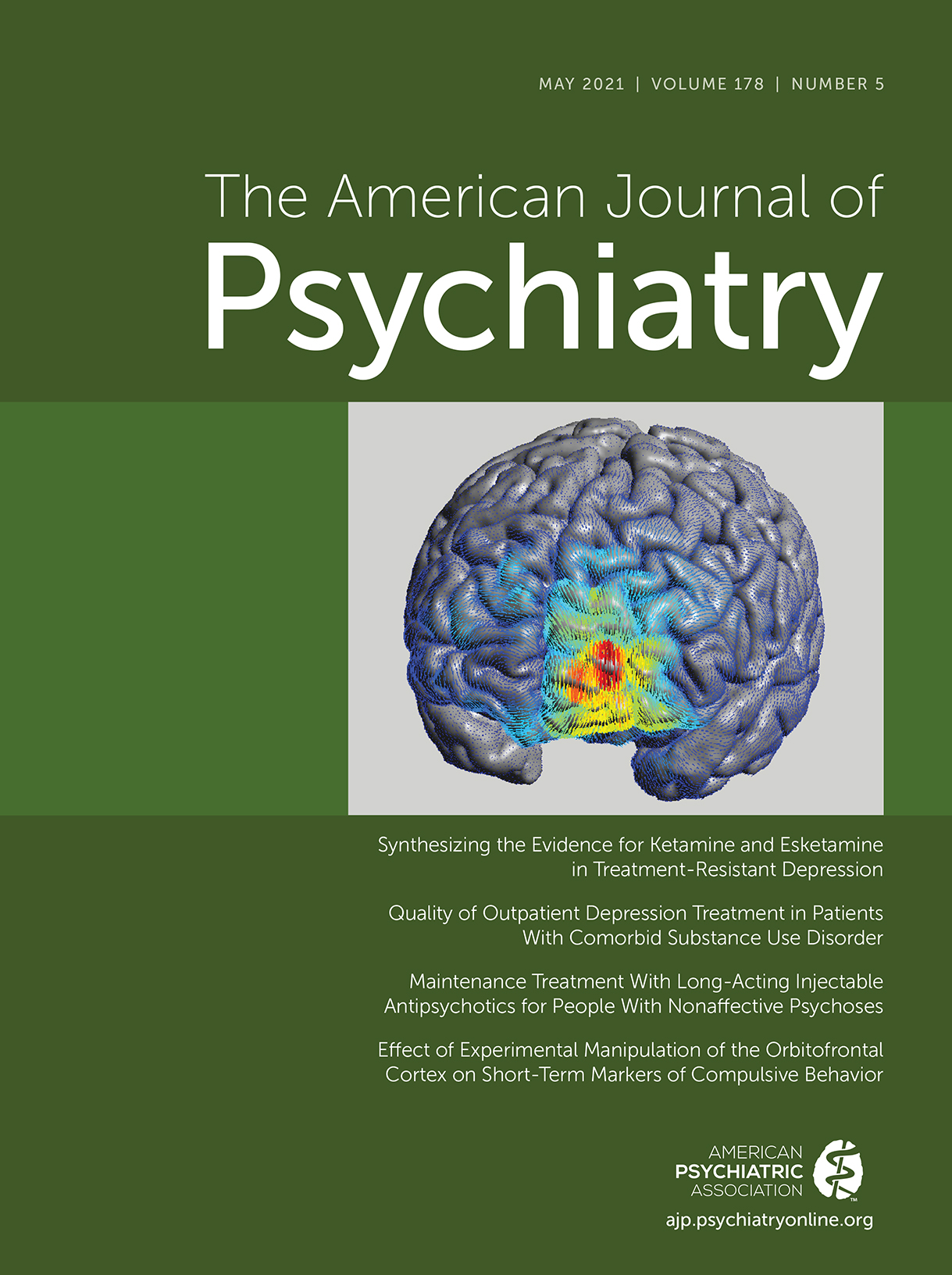

One focus in these meetings was a problem that we have in psychiatry, namely the lack of valid animal models for many of our disorders or for screening for agents that could be effective in treating patients with them. Many of the behavioral models used to screen for potential new drugs are based on behavioral effects of known antidepressants, the original examples of which were discovered serendipitously to have specific clinical effects. The result has been to develop agents that are “me too” drugs rather than agents that have unique pharmacological and clinical effects. One method for dealing with concerns regarding the predictive value of effects in animal models has been to develop approaches for so-called target validation in humans, where a particular agent is studied for its ability to enter the brain, its brain receptor occupancy, or its effect on an imageable brain function involving a putative circuit that could underlie a clinical construct that is a key component of a disorder. The first two are important issues because in psychiatry, a lack of brain penetrance or receptor binding usually results in poor clinical effects for a prospective agent. These two assessments are typically performed using positron emission tomography. The third is important for demonstrating a behavioral effect in man and is done via functional MRI (fMRI). One needs, however, to be able to demonstrate that ultimately the behavioral effect will translate into a potential treatment for a clinical problem. In the end, establishing clinical effects of specific agents is the goal (i.e., the proof is in the clinical pudding). Undue emphasis on the target validation rather than on determining clinical effects is perhaps as likely to delay drug development as it is to facilitate it. The Costi et al. article regarding the study of ezogabine demonstrates some of the conundrums of the target validation approach.

In 1999, when I was President-Elect of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP), I organized a teaching day at the annual meeting of the ACNP around using fMRI to assist in drug development. This was spurred by the impressive work that my Stanford colleagues (Gary Glover, Norbert Pelc, and Allan Reiss) were doing with blood-oxygen-level-dependent-signal fMRI in psychiatric disorders. I was so impressed by the sensitivity of the observed signal in the brain in response to then largely cognitive tasks that it seemed important to bring this to the ACNP. The meeting was well attended and was seemingly very successful. It has, however, taken considerable time to reach where we are today with beginning to use technology to assess or evaluate effects of specific agents. While these efforts are promising, this and other recent studies demonstrate some real potential problems for the field, particularly how we are to interpret imaging and clinical findings when they appear to be discrepant (

1,

4,

5).

The Costi et al. study declared a primary endpoint for ezogabine as change in ventral striatal activity. As the authors indicate, they did this in keeping with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) initiatives related to research domain criteria (

6), as well as to “fast fail,” a drug screening program aimed at speeding successful medication development (

7). The specific fMRI approach used here is based on the notion that the ventral striatum controls hedonic responses and that anhedonia is a core behavioral construct. Studies have shown that activity in this circuit appears to be related to hedonic capacity, which many would view as a key component of depression. The approach clearly eschews looking at major depression as an overall construct. Rather, it attempts to demonstrate that a drug of interest engages a putative brain target, usually a specific circuit, that affects a clinical function (in this case hedonic response) and then to use target engagement results in the decision making as to whether to further pursue its development for a particular indication, such as major depression. This approach avoids misinterpreting the potential clinical benefit from a drug that could arise from overinterpreting results from small open-label or blinded phase II studies. In the Costi et al. study, ezogabine appeared to have an effect on change in ventral striatal activity, but it did not attain statistical significance. In contrast, there were powerfully robust, statistically significant effects of the drug that were observed on depressive symptoms, as well as on specific components such as anhedonia, all secondary endpoints. In the NIMH target validation scenario, the consequence might be that further development of this drug should not be pursued for anhedonia or related disorders (e.g., major depression). In another recent study using a similar approach, Krystal et al. (

4) reported that a kappa antagonist was more effective than placebo in its declared primary, increasing ventral striatal activity, but did not separate from placebo on its secondary antidepressant and antianhedonic effects. Costi et al. point out that the Krystal study was larger than theirs and that both studies demonstrated similar effect sizes for striatal activation. In another study, Kantrowitz et al. (

5), from Lieberman’s group, reported data from an NIMH-funded study on a novel mGluR2/3 agonist as a potential antipsychotic (antischizophrenic) drug. Results did not confirm the primary imaging endpoint involving effect on anterior cingulate activity in response to challenge with the psychotomimetic ketamine; however, at the higher dose tested, the drug appeared to have positive, statistically significant clinical effects on psychotic symptoms.

In drug development in this country, regulators and investigators have taken the approach that the principal investigator must a priori declare the primary outcome to assess the key results and state a set of secondary outcomes to be examined after achieving the primary endpoint. Some would argue that if the primary fails, one should not even entertain the secondary endpoints. In light of this, how are we to interpret these various studies that use two different outcome domains? In the Costi et al. and Kantrowitz et al. studies, should we disregard the potentially impressive clinical effects because the drugs failed on the primary imaging marker? Or because the positive clinical effects were observed in small sample sizes that with other agents may not have yielded reproduceable results in later studies? Should we use the failed imaging data to discourage investing in potentially effective agents or in follow-on drugs that work through those mechanisms? The neurosteroid brexanolone, for postpartum depression, is now FDA approved for postpartum depression. Its positive phase-II trial was very small (less than half that of the Costi et al. study), as were its two positive phase-III trials (

3,

8). In brexanolone’s case, the approach was based on the hypothesis that allopregnanolone was low in postpartum depressives. Conversely, should we invest in kappa antagonists that increased ventral striatal activity in the Krystal et al. study but may not have relevant clinical effects? One may argue that we need to do relatively large, early studies to assess the clinical or biological effects—but does that not defeat the purpose of the approach to speed drug development by doing target validation? Since we do not really have evidence that the ventral striatal defect on fMRI is a sensitive and/or highly powerful marker for anhedonia or depression or for screening for drug effects, what do these data really tell us? In the end, again the clinical effects need to be demonstrated for successful drug development. Reliance on these biological markers may be premature. They appear to require more investigation (particularly for estimating the validity vis-á-vis clinical significance, as well as effect size and power for optimization for use in studies) before determining potential likelihood of success for a specific agent. Still, the imaging approaches may help us validate key clinical phenomena (e.g., anhedonia) with underlying demonstrable biology, and these can ultimately inform key decisions as to whether to develop a specific agent. However, absent knowing whether such screening is highly valid and sensitive today, we may be throwing out important opportunities.

What should we do now? Costi et al. make some cogent suggestions regarding using alternative statistical methods for assessing outcomes: “a more lenient alpha level, a futility design, or a Bayesian approach.” These specifics may help, but what may be most important is to have a better sense of agreement in the field about how to design early clinical trials, how to analyze results, and how best to interpret biological versus clinical outcomes using such approaches. Should we “suspend” conventions regarding primary and secondary outcomes, particularly if they are in different domains? Should we switch from reliance on p values to using effect sizes as has been argued by Kraemer (

9)?

On biomarker application, as indicated above, do we have enough data to know that these markers are indeed sensitive or valid? Should we spend more time on validating the marker or imaging paradigm before unleashing them on novel drugs? After all, these are not culture and sensitivity measures used in infectious disease. Should we not assess the drugs for clinical benefit in these proof-of-mechanism studies?

Without thinking through the approach, such target validation methods may actually do more harm than good in developing the next generation of effective agents. Still, Costi et al., from the Matthew and Murrough collaborative research group, are to be congratulated for following a line of research from animal models to open-label study and then to a double-blind pilot trial on a new lead that if replicated in phase-III studies could prove to be of great benefit to millions who suffer from major depression. This is an innovative piece of work.