Methods

The results described here are derived from data obtained during a two-site study examining the effect of fluoxetine compared with placebo in preventing relapse among 93 weight-restored women with anorexia nervosa, ages 16 to 45 years (

5). In short, patients were eligible to enter the study after they had successfully completed weight restoration treatment in an inpatient or day-hospital program during which their body mass index (BMI) reached at least 19 and remained at or above that level for 2 weeks. Patients were then randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine or placebo, and the dosage was raised to 60 mg/day or the equivalent of placebo over 1 week. Patients were then discharged and followed for up to a year or until they relapsed. The dosage of fluoxetine could be raised to 80 mg/day if the patient was deteriorating as judged by a study psychiatrist. After discharge, patients also received outpatient cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for up to 1 year—twice weekly for the first month, once weekly for the second through 11th months, and every other week for the last month. Patients were weighed at each visit and were asked about whether they had engaged in binge eating or purging. For the purpose of the present analysis, since all patients entered the study with a BMI greater than 18.5, the lower limit of normal described by the CDC (

https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html), patients were considered to be in remission at the time of study entry.

The original study and the present analysis were approved by the appropriate institutional review boards at both sites, and all patients provided written informed consent.

The primary aim of the original study was to determine whether fluoxetine extended the time to relapse compared with placebo; the primary outcome measure was time to relapse, and it was examined via survival analysis utilizing a Cox proportional hazards regression. Forty of the 93 patients completed the study and therefore were considered not to have relapsed. A key question was how many of the other 53 patients had relapsed.

The definition of relapse, as described in the original study, involved several facets. First, 20 patients met a priori criteria for severe deterioration and were withdrawn from the study and referred to a higher level of care. As stated in the original report, the criteria for withdrawal were “1) the participant’s BMI fell to or below 16.5 for 2 consecutive weeks; 2) severe medical complications (other than low weight) arose as a result of the eating disorder; 3) the participant was judged to be at imminent risk of suicide; or 4) the participant developed another severe psychiatric disorder requiring treatment.” These 20 patients were classified as having relapsed. In addition, six patients were withdrawn by the investigators because of nonadherence or possible side effects. These patients were classified according to the criteria described below.

We anticipated that a substantial number of patients would voluntarily withdraw from treatment during this 52-week study. We therefore developed three sets of a priori criteria to assess whether any of them had relapsed.

In the primary, and most conservative, analysis, all patients who failed to complete the study, for any reason, were classified as having relapsed. There were two reasons for choosing this definition for our primary method of analysis. First, it removed any investigator judgment from deciding who had relapsed, and therefore protected the results from potential bias if the investigator suspected that the patient was on fluoxetine or placebo. Second, it was essentially identical to the criterion utilized by Kaye et al. (

6)—the length of time patients remained on fluoxetine versus on placebo, assessed via survival analysis; patients who stopped taking medication were considered to have relapsed. Kaye and colleagues’ study suggested that fluoxetine substantially reduced the rate of relapse, and a major goal of our 2006 study (

5) was to attempt to replicate and extend the results of that study. By this criterion, all 53 patients who failed to complete the study were classified as having relapsed.

Patients who did not complete the study were classified as having relapsed in two other ways. In the least conservative method, none of the patients who dropped out or were withdrawn for reasons other than severe deterioration as defined above were considered to have relapsed at the time they ended participation; that is, their data were censored. Therefore, only the 20 patients who were withdrawn from the study because of severe deterioration as defined above were classified as having relapsed. This analysis, like the first one described, minimized potential bias.

The third way of classifying noncompleters relied on a clinical assessment of the patient’s condition at the time she dropped out. Before breaking the blind regarding assignment to fluoxetine or placebo, the investigators classified noncompleters as having relapsed on the basis of the following clinical criteria, as described in the original report (

5):

For the third analysis, dropouts were considered to have relapsed if they met any of the following criteria at the time they chose to end participation in the study: 1) had a BMI less than 17.5; 2); were binge eating and/or purging two or more times per week for the 4 weeks prior to dropping out; or 3) exhibited depressive and/or anxiety symptoms sufficient to interfere with functioning (e.g., serious suicidal ideation).

By these criteria, 44 patients, including the 20 withdrawn for severe deterioration, were classified as having relapsed. In other words, 24 of the 33 patients who dropped out or were withdrawn for reasons other than severe deterioration were clinically judged to have relapsed.

Survival analyses were conducted using each of these methods for classifying noncompleters, and none showed any indication that fluoxetine extended the time to relapse compared with placebo.

The purpose of the present analysis was to describe the time course of relapse following entry into the study. As the primary measure of relapse for this analysis, we chose to use the last method of classifying noncompleters described above—based on clinical status of the patient at the time she ended participation in the study—because it captured the patient’s clinical state at the time she dropped out. In the online supplement, we also describe the time course of relapse using the primary method of classifying noncompleters used in the original study, in which all noncompleters were classified as having relapsed.

We chose not to model the time course of relapse using the criterion that only the 20 patients who exhibited severe deterioration and were withdrawn by the investigators were considered to have relapsed. An implicit assumption underlying this criterion is that none of the other 33 patients who failed to complete the study had relapsed. We do not believe this is a clinically sound assumption. In other words, such an analysis would be a description of the time to severe deterioration, not the time to relapse as clinically judged.

In the present analysis, for each day following entry into the study (which occurred 1 week prior to discharge from acute care), we first calculated the risk of relapse over the following 60 and 90 days based on the Kaplan-Meier estimator that was used to construct the survival curve in the original study (

5). To describe the time trend of the risk function, we fitted a parametric function to approximate the Kaplan-Meier estimator based on a nonnormalized location-shifted gamma function: p(t)=γ*(t−c)*e

α(t−c), where t is the number of days following entry into the study and p(t) is the probability of relapse in the subsequent 60 or 90 days; it can be derived that (c−1/α) is the day at which the greatest risk occurs. This family of distributions is used to fit survival outcomes to accommodate nonlinear hazard functions (

7). Parameters α, γ, and c were estimated by fitting an ordinary least squares regression to the conditional probabilities obtained from the Kaplan-Meier estimator.

Results

At the time of entry into the study, the patients’ mean age was 23.3 years (SD=4.6) and their mean BMI was 20.3 (SD=0.5). The mean duration of illness was 4.5 years (SD=3.6).

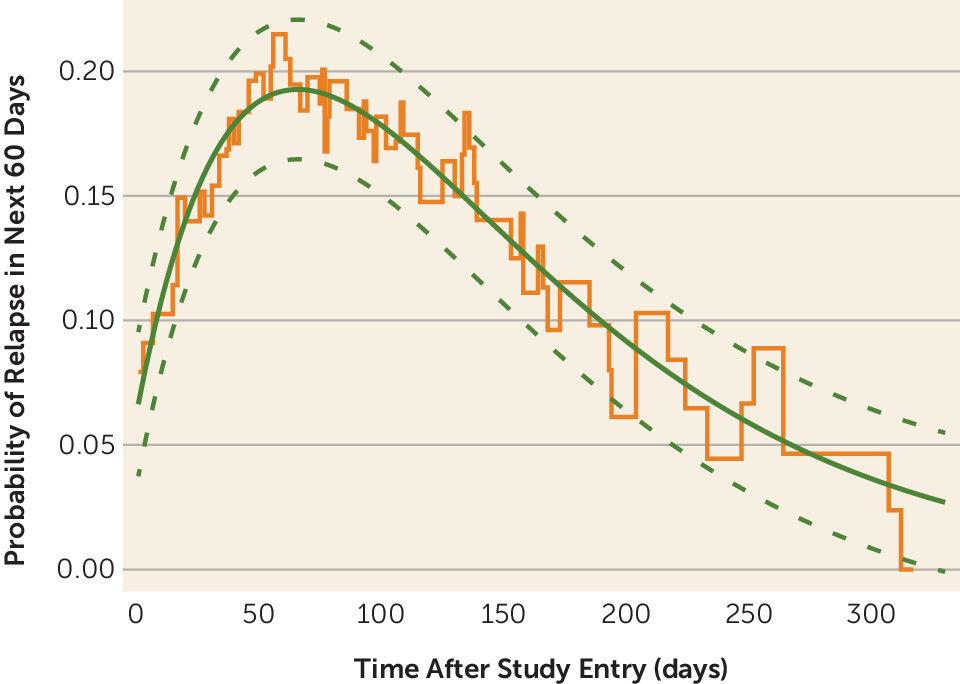

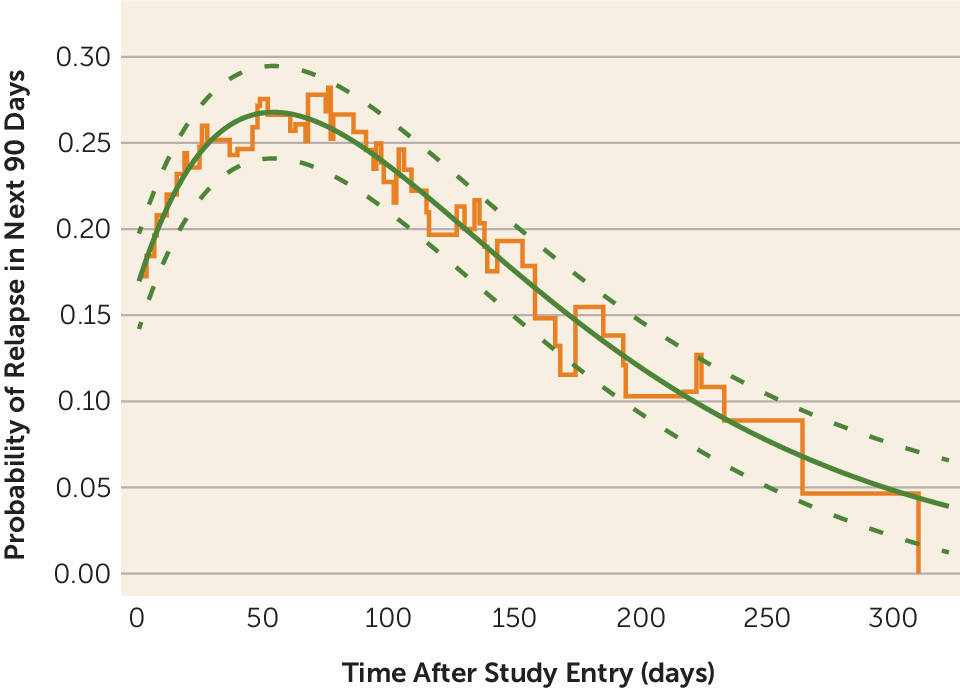

As shown in

Figures 1 and

2, the risk of relapse as judged clinically in the following 60 and 90 days rose immediately after entry into the study, reached a peak after approximately 60 days, and then gradually declined. The gamma parametric curves fit the nonparametric Kaplan-Meier estimator (step function in orange shown in the figures) adequately, and almost all data points fall within the 95% confidence interval of the fitted curve (p<0.001 versus a linear fit). There was no indication of an inflection point at which the risk of relapse fell precipitously after the initial peak.

Figures S1 and S2 in the online supplement show the risk of relapse in the 60 and 90 days following entry into the study using the criterion that withdrawal from the study for any reason was considered a relapse. The results of these analyses are similar to those using the clinical criteria for relapse.

We compared the estimated peak relapse rates over the next 60 days for the following: relapse judged clinically at the time of study withdrawal (

Figure 1) versus any withdrawal viewed as a relapse (see Figure S1 in the

online supplement); site (New York versus Toronto); and subtype (binge-eating/purging versus restricting). The peak risks of relapse for the two criteria for judging relapse (dropouts classified clinically versus all dropouts classified as having relapsed) did not differ significantly (19.3% [SD=1.4] and 21.7% [SD=1.6], respectively; p=0.13). The peak risk of relapse at the New York site was significantly greater than that at the Toronto site (32.1% [SD=4.2] compared with 10.5% [SD=3.4]; p<0.001), and the peak risk of relapse for patients with the binge-eating/purging subtype was significantly greater than for patients with the restricting subtype (24.6% [SD=3.1] compared with 15.3% [SD=2.3]; p<0.01). The days of peak relapse differed significantly for all these comparisons. For study withdrawal judged clinically versus all withdrawals classified as having relapsed, the days of peak relapse were 66.0 days (SD=0.7) and 52.9 days (SD=0.7), respectively (p<0.001). For New York versus Toronto, the days of peak relapse were 56.9 days (SD=1.1) and 110.3 days (SD=4.0), respectively (p<0.001). For the binge-eating/purging versus the restricting subtype, the days of peak relapse were 70.4 days (SD=0.9) and 64.0 days (SD=1.1), respectively (p<0.001). Comparisons of relapse rates over the next 90 days yielded similar results (see the

online supplement).

Discussion

This analysis has both strengths and limitations. Important strengths are that the data were derived from a prospective, controlled trial and patients entered the study at similar, normal BMIs. In addition, criteria for relapse were based on clinical assessment and were specified a priori. Although maintenance of a minimally normal body weight is a sine qua non for remaining in remission from anorexia nervosa, it has been suggested that a full range of physical, behavioral, and psychological measures be used to assess remission and recovery (

8); therefore, a potential limitation is that the criteria utilized in the present analyses were largely based on body weight. All patients had been fully weight-restored via highly structured behaviorally oriented intensive treatment; the degree to which the present results apply to patients with anorexia nervosa treated in other settings and to other degrees of weight restoration is uncertain. Patients were all women, 16 to 45 years of age, and were followed for no more than 12 months. Finally, it might be argued that, since this study was initiated over 20 years ago, it employed a now-outdated psychological treatment (CBT); unfortunately, no clearly superior treatment methods have since been identified (

9).

Our analysis indicates that there was a transient increase in the risk of relapse in the 2 months following discharge from an acute care setting into outpatient care. Even though CBT was provided to all patients twice weekly for the first month and then once weekly until the last month of the study, it is likely that the substantial decrease in support and monitoring of behavior contributed to this increase. A previous analysis of data from this study (

10) and subsequent work (

11,

12) suggest that critical elements increasing the risk of relapse are a reduction in caloric intake from the amount consumed in the last weeks of acute treatment and the resultant rapid weight loss immediately following entry into outpatient treatment. That is, patients who quickly returned to their pretreatment patterns of food intake were at high risk for rapid relapse. After the first 2 months, the risk of relapse fell steadily over the course of the study, so that the longer a patient went without relapsing, the lower their risk of subsequent relapse. These results do not follow the model suggested by Frank et al. (

2), in which a point of rarity in the change in risk over time can be identified. Therefore, at least over the year following discharge from acute treatment, it is not possible to identify empirically a duration of remission at which recovery can be declared.

The comparisons of the peak relapse rates for the New York versus the Toronto site, and for the binge-eating/purging versus the restricting subtype of anorexia nervosa, are consistent with the comparisons of the time to relapse in the original study (

5). That is, the peak relapse rate was significantly lower at the Toronto site and for patients with the restricting subtype. The peak relapse rate when dropouts were classified clinically did not differ significantly from that when all dropouts were classified as having relapsed. The day of peak relapse using the latter criterion occurred earlier, likely because all individuals who voluntarily withdrew soon after entering the study were classified as having relapsed. However, we believe comparisons of the time courses of relapse of different groups of patients using parameters derived by the model employed in the present analyses should be interpreted with caution. The statistical model yields a specific day, with a small confidence interval, on which the relapse rate over the following 60 or 90 days is estimated to have been greatest. However, examination of the curves indicates that rate of relapse gradually rose and fell, rather than reaching a sharp peak. More importantly, our aim in the present analyses was to describe the time course of the conditional risk of relapse in the next 60 or 90 days given that no relapse has occurred by a certain day, not to compare the effect of site or disorder subtype on time to relapse. These factors were examined in the original study using well-established methods of survival analysis (

5).

Only a few studies have attempted to develop a definition of recovery from anorexia nervosa based on an analysis of the course of patients over time, and comparisons are difficult because of differences in methodology and in definitions of remission and recovery (

13). Kordy et al. (

3) attempted to apply the perspective articulated by Frank et al. (

2) to follow-up data from 233 patients with anorexia nervosa observed for 2.5 years, and concluded that “duration is not a strong predictor of stability of the stages of full remission and recovery.” Recently, De Young et al. (

4) analyzed data from 246 women with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa who were initially assessed between 1987 and 1991 and followed for a median of 9.5 years. De Young et al. found that among patients with anorexia nervosa, after symptom remission had occurred, there was a gradual decrease in the risk of symptom return over time, and they were unable to identify an inflection point when the risk of relapse changed dramatically. Therefore, neither of these studies, nor the present analysis, was able to identify empirically a duration of symptom remission that supported a declaration of recovery. Rather, the longer the duration of remission, the lower the risk of relapse. Relatedly, it is of interest that in a review of studies of the time course of major depression, the focus of the paper of Frank et al., de Zwart et al. (

14) similarly found little evidence for a specific duration of remission after which a patient could be declared recovered; the risk of relapse gradually diminishes as the duration of remission lengthens.

The present analysis highlights the fact that adult patients with anorexia nervosa are at increased risk of relapse in the first months following discharge from acute treatment that results in full weight restoration, suggesting a need for step-down care focusing on maintaining caloric intake—for example, via partial hospitalization, a day program, and/or frequent follow-up and relapse prevention–focused treatment during this period. Notably, the time course of relapse described here for anorexia nervosa is quite similar to the high risk of suicide in the first weeks following discharge from hospitalization for other psychiatric disorders, underscoring the risk of symptom resurgence following discharge from intensive care (

15).

In summary, our results demonstrate that, after approximately 2 months following successful acute treatment, the risk of relapse in anorexia nervosa progressively decreases over time. Therefore, although it may be useful for administrative or research-oriented reasons to declare that patients with anorexia nervosa have recovered after they have been symptom free for a specified length of time, it should be recognized that such an interval must be chosen somewhat arbitrarily, as no specific length of time is suggested by the currently available empirical evidence.