Decades of research characterize attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as a neurobiological disorder typically first detected in childhood that persists into adulthood in approximately 50% of cases (

1–

3). Substantial scientific work has examined ADHD persistence—the extent to which children with ADHD continue to meet DSM criteria for the disorder in adolescence and adulthood. However, less research has investigated remission (loss of symptoms and impairment), recurrence, and recovery (sustained remission over time). Most longitudinal ADHD studies simply define remission as “failing to meet DSM criteria,” with few attempts to identify or define distinct subtypes and patterns of remission (

4–

6). Understanding common trajectories of ADHD remission, recurrence, and recovery is critical to informing provider, patient, and family treatment decisions.

In the most detailed past efforts to characterize the trajectory of ADHD, Biederman et al. (

7,

8) demonstrated that 65%−67% young adults (mean age, 22 years) with childhood ADHD no longer met full DSM criteria. On the other hand, the vast majority (77%−78%) had clinically elevated ADHD symptoms, impairment, and/or continuation of ADHD treatments. Thus, most participants who were classified as having remitted ADHD on the basis of traditional DSM guidelines still experienced impairing subthreshold ADHD symptoms or experienced “remission” only when receiving ADHD treatment (e.g., stimulant medication). Biederman et al. detected a subgroup of children whose ADHD appeared fully remitted in young adulthood (∼22%−23%), signifying possible recovery from ADHD. However, the longitudinal course and optimal definition of full remission remains understudied.

Most longitudinal work on ADHD remission and persistence reports only a single-time snapshot of functioning, even though ADHD is considered a life-course disorder (

2,

4–

6,

9,

10). There is virtually no scientific information on the extent to which individuals sustain remission long-term (i.e., recover from ADHD symptoms and impairments), experience recurrence of ADHD after remission (i.e., remission was temporary), or fluctuate between full remission, partial remission, and ADHD persistence, that is, whether ADHD might be a waxing and waning disorder. If remission is typically temporary, practice guidelines should emphasize the need for continued ADHD screening or monitoring after remission and for rapid response to symptom reemergence. If ADHD tends to wax and wane, factors modulating phenotypic expression must be identified and person-environment fit emphasized as a crucial framework for evaluation and treatment over time.

In this study, we investigated longitudinal patterns of remission from ADHD in the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD (MTA) follow-up (

3,

10,

11), which utilized multi-informant assessment to measure ADHD symptoms, impairments, treatment utilization, and comorbidities across 16 years, spanning childhood through young adulthood. Using a thorough stepwise procedure, we 1) validated age-appropriate full remission symptom thresholds in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood; 2) examined detailed symptom, impairment, comorbidity, and treatment utilization information to classify participants’ ADHD as fully remitted, partially remitted, or persistent at each of eight MTA follow-up assessments; and 3) outlined longitudinal patterns of ADHD remission, recurrence, and recovery with attention to onset, duration, type (full or partial), and course of remission.

METHODS

The MTA (

12) originally compared 14 months of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments for 579 children (7.0 to 9.9 years old) with DSM-IV ADHD, combined type. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table S1 in the

online supplement. Two years after baseline, 289 classmates were recruited as a local normative comparison group. The MTA continued 14 years of prospective follow-up assessments approximately biennially (eight assessments) until 16 years after baseline (

13–

16).

Participants

The subsample analyzed here (N=558; 95.3% of the original sample) includes participants with at least one follow-up assessment (beginning 2 years after baseline). Retention in adulthood (among participants who completed a 12-, 14-, or 16-year assessment) was 82% for the ADHD group (N=476) and 94% for the normative comparison group (N=272). On average, participants completed 6.2 of eight possible follow-ups (SD=2.25). Average age was 10.44 years (SD=0.87) at 2 years and 25.12 years (SD=1.07) at the 16-year follow-up. The subsample did not differ from the full sample on any baseline variable.

Procedures

Follow-up assessments were administered to participants and parents at 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 years after baseline by bachelor’s-level staff who were closely supervised and trained to be objective. Teacher ratings were obtained at childhood and adolescent assessments. For 2.3% of adult assessments, a parent was unavailable and ratings were collected from a nonparental informant (e.g., partner, sibling).

Measures

ADHD symptoms.

Child and adolescent symptoms were measured using the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham rating scale, completed by parents, teachers, and adolescents (

17,

18). Symptoms in adulthood were measured using the Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale, completed by participants and parents (

19). Both instruments measure DSM-IV-TR ADHD symptoms. Respondents rated symptoms over the previous 4 weeks on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). Scores of 2–3 indicated symptom presence, as is standard practice (

20).

Impairment.

In childhood and adolescence, impairment was measured using the parent-report Columbia Impairment Scale, which assesses 13 impairment domains on a severity scale ranging from 0 to 4 (

21,

22). In adulthood, the parent- and self-report Impairment Rating Scale was used to rate impairment globally and in 11 domains on a scale from 0 (no problem) to 6 (extreme problem) (

23). For the present study, we validated Columbia Impairment Scale and Impairment Rating Scale thresholds for “absence of impairment” (see section S2 in the

online supplement) using normative data from the comparison group. These analyses indicated that for the Columbia Impairment Scale, absence of impairment was optimally defined as a rating ≤1 on all items. For the Impairment Rating Scale, absence of impairment was optimally defined as a rating ≤2 on all items (combining parent- and self-reports using an OR rule) (

24).

Psychiatric diagnoses.

The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) (

25) was administered using parent- and self-reports. Self-report began at the 6-year follow-up; the DISC was not administered at the 10-year follow-up. The DISC is a structured interview that queries the presence of DSM criteria using screening questions and supplemental probes. All disorders assessed by the DISC were documented. For a list of included disorders, see section S5 in the

online supplement.

Service utilization.

The Services for Children and Adolescents–Parent Interview (SCAPI) (

26) was administered through the 10-year assessment. It collected between-assessment estimates of daily dose and number of days treated for ADHD medications, as well as psychosocial and educational intervention utilization (including frequency, duration, and type of services). Similar information was collected at ages 12 through 16 using the Health Questionnaire, which queried therapy and medication, including dosages, duration, and type of services (

11).

Analytic Plan

Defining full remission.

Our first task was to empirically validate a “full remission” symptom count threshold that 1) represents normative symptom count levels based on normative comparison group percentiles (normativity) and 2) maximizes sensitivity and specificity in detecting childhood ADHD cases without residual impairments at follow-up (correct classification). We separately analyzed data from child (age <12 years), adolescent (ages 12–17.99 years), and young adult (age ≥18 years) follow-ups to consider developmentally specific thresholds. After reviewing normativity and correct classification data for each developmental group, selection of final thresholds considered parsimony, theoretical clarity, and ease of use by clinicians.

We began with four face-valid candidate definitions for full remission using equivalent thresholds for inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptom counts (i.e., three, two, one, or none of both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms). We did not test four-, five-, and six-symptom remission thresholds given that five- and six-symptom thresholds indicate the

presence of elevated symptoms in the DSM-5 A criteria for ADHD, and that the four-symptom threshold has repeatedly demonstrated validity as a norm-based threshold for adolescent and adult ADHD symptom elevations (

1,

2,

27).

Each candidate definition used reports from all available informants, which were integrated using an OR rule: if any informant endorsed a symptom, it was counted as present (

24). To prevent false negative symptom and impairment reports due to underreporting by participants with ADHD (

3,

27), we required those meeting the “remitted” definition (and the “unimpaired” criterion) to have at least one other informant report to corroborate the lack of difficulties. Thus, to be categorized as being in full remission, one must be below the symptom threshold according to combined information from all informants, including at least one besides self.

With respect to normativity, we calculated normative comparison group percentiles for each symptom count threshold and developmental group. In this analysis, we excluded 31 normative comparison group participants with a baseline diagnosis of ADHD. Empirical percentiles were calculated as m + 0.5k, where

m is the percentage of the comparison group scoring below threshold, and

k is the percentage of the comparison group with scores that were at threshold. Based on standard norming procedures for mental health symptom measures, scores below the normative comparison group 84th percentile were considered in the normal range (

28).

With respect to correct classification, receiver operating curve (ROC) analyses provide an index of diagnostic accuracy (area under the curve, AUC) for each candidate symptom count threshold (true positives plus true negatives divided by total sample) that optimizes both sensitivity and specificity (

29). Absence of impairment (see section S2 in the

online supplement) was the ROC criterion (i.e., indicating that symptoms were no longer clinically significant). Within each developmental period, when participants possessed multiple data points, we randomly selected one per participant for the ROC analyses.

Detecting cases with full remission of ADHD.

We evaluated all cases for full remission of ADHD at each of eight follow-up assessments. We used a stepped procedure based on an AND rule that first required symptoms to fall below the full remission threshold according to all informants, then required absence of clinically significant impairment, and, finally, required discontinuation of all ADHD intervention for at least 1 month prior to the assessment (see section S3 in the

online supplement). Exclusion of currently treated cases from the full remission category does not imply confidence that treatment is in every case dampening symptom expression; rather, it conservatively assures that symptom remission is not due to active treatment. Services for non-ADHD difficulties were allowed. For each assessment, we classified remaining cases as “persistent” or “partially remitted.” We utilized a previously validated definition of persistence (

3,

10), which applied the DSM-5 symptom threshold (five or six symptoms of either inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity, depending on age) using the Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale (or the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham rating scale) and an impairment threshold of 3 or higher on the Impairment Rating Scale (or the Columbia Impairment Scale). Partially remitted cases met criteria for neither persistence nor full remission.

Consideration of impairment due to other disorders.

Following the stepped review procedure, we reexamined cases below the symptom threshold with continued impairment to estimate whether this impairment was due to residual ADHD symptoms (leading to a classification of partial remission) or to other psychiatric diagnoses, including substance use disorders (leading to a classification of full remission). Because the DISC does not address differential diagnosis, we assembled an expert clinical panel to review cases with clinically significant impairment that might be due to a problem other than ADHD. For each case, three board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrists and four licensed clinical psychologists reviewed psychiatric diagnoses, domains of impairment, ADHD symptom endorsements, and treatment utilization. They judged whether reported impairments were best explained by residual ADHD symptoms or a concurrent substance use or mental disorder. Most decisions (80.9%) were unanimous; no split vote had more than two dissenters. For further details, see section S5 in the

online supplement.

Longitudinal patterns of remission, recurrence, and recovery from ADHD.

Recurrence was defined as meeting criteria for “persistence” (full recurrence) or “partial remission” (partial recurrence) after a period of full remission. We defined recovery as full remission of ADHD sustained for at least two consecutive assessments without a subsequent recurrence (full remission until study endpoint). On four occasions, a data point was missing but was bookended with two episodes of full remission. Here, continuity of recovery was assumed but the missing data point was not counted when the duration of full remission was calculated. In addition to the recovery pattern, three additional longitudinal patterns were defined. Stable persistence was persistent ADHD over the entire follow-up. A fluctuating pattern was defined by at least two changes in classification since baseline diagnosis of ADHD, in the absence of the recovery pattern. Stable partial remission was defined as displaying one classification change from persistent ADHD to partial remission that continued until study endpoint.

DISCUSSION

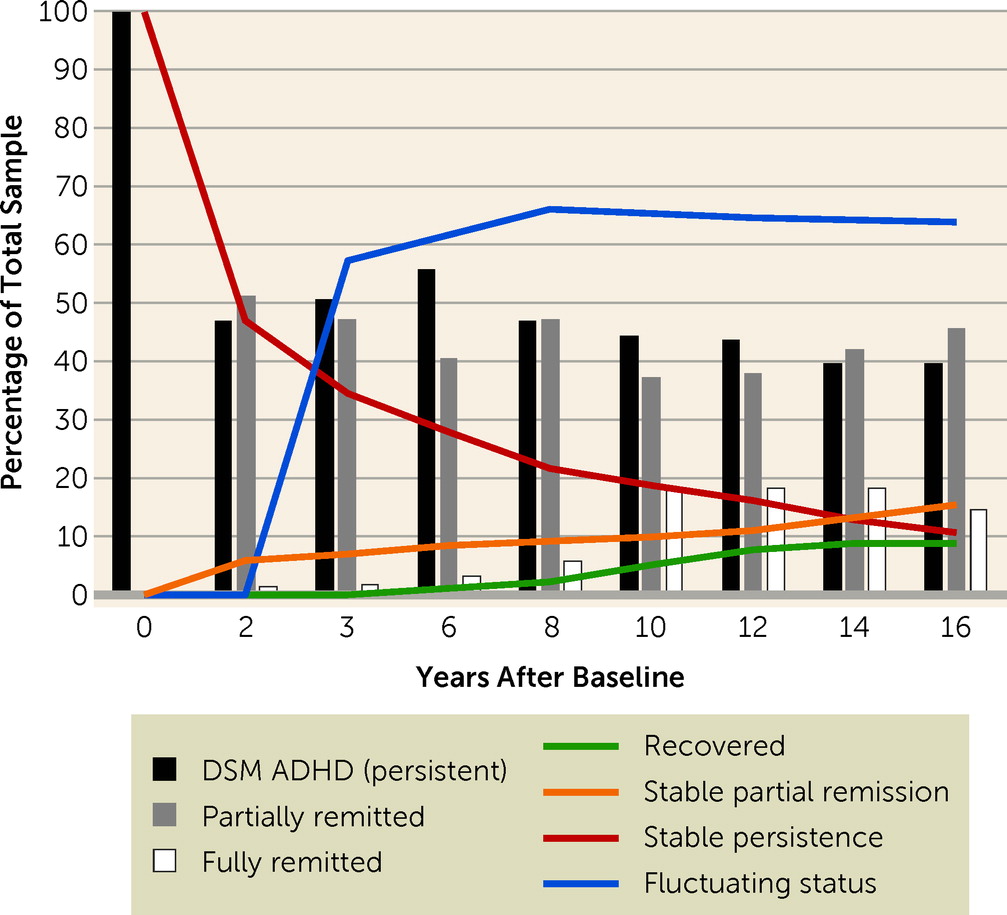

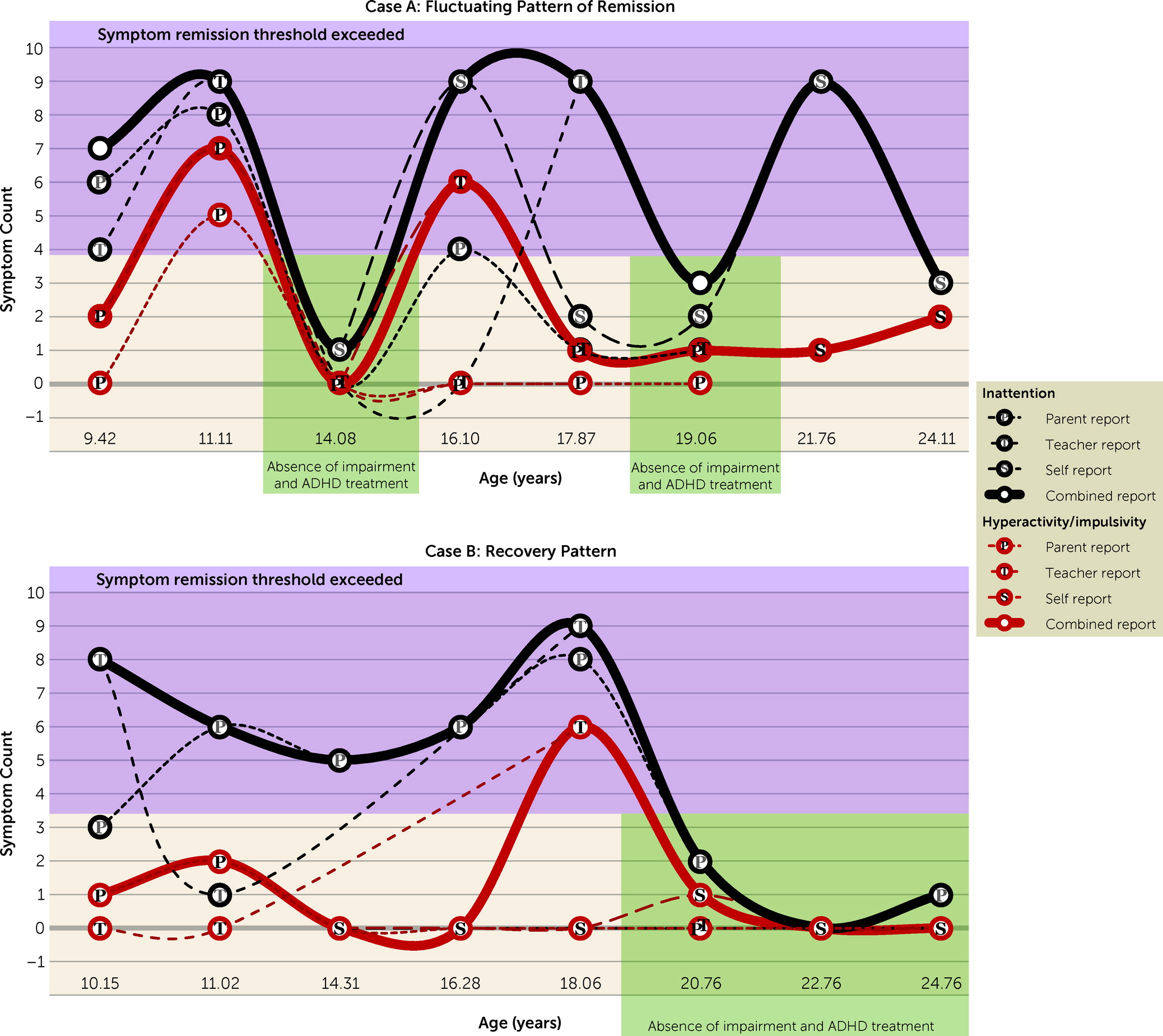

Our goal in this study was to understand the longitudinal course of ADHD remission from childhood to young adulthood. The results indicate that approximately one-third of children with ADHD experienced full remission at some point during 14 years of prospective longitudinal study. A majority of these fully remitting youths (∼60%) experienced full or partial recurrence of ADHD after the initial period of full remission. Only 9.1% of the children with ADHD demonstrated recovery from ADHD (i.e., sustained remission to study endpoint; mean age, 25 years) and only 10.8% demonstrated stable ADHD persistence across all time points. For most of the sample (63.8%), the follow-up period was characterized by fluctuating persistence and remission (full or partial) in the absence of recovery.

The results are consistent with previous findings that, at a single time point, most individuals who no longer meet DSM criteria for ADHD still experience elevated symptoms or impairments or are actively treated with medication (see

Table 2) (

7,

8). In the present study, full remission at a single assessment ranged from 1.4% to 18.5%. Young adult assessments corresponding temporally with Biederman and colleagues’ estimates (i.e., 12- and 14-year assessments) demonstrated comparable full remission rates (18% compared with 22%−23%) (

7,

8). Expanding on previously reported MTA findings (

10), the present study indicates that 40%−50% of the ADHD group met DSM criteria for ADHD at any given follow-up. However, remission was typically partial, rather than full. The high prevalence of partial remission is consistent with the finding of Hechtman et al. (

10) that many MTA ADHD group participants who did not meet ADHD symptom criteria in adulthood still suffered significant impairments. We also confirmed that most recoveries from ADHD begin in adulthood (see

Table 3), although this finding could be partially an artifact of having fewer later assessments to detect recurrences.

The MTA’s longitudinal perspective highlights that full remission at a single time point should not be conflated with recovery from ADHD. Only 9.1% of the MTA sample experienced recovery (i.e., sustained remission for multiple time points until study endpoint). After a period of full remission, recurrent ADHD symptoms were the rule, rather than the exception. Overall, the results suggest that over 90% of individuals with childhood ADHD will continue to struggle with residual, although sometimes fluctuating, symptoms and impairments through at least young adulthood. Our more nuanced longitudinal estimate of remission challenges claims that approximately half of children with ADHD outgrow their difficulties by adulthood.

On the other hand, few participants (10.8%) were characterized by a stable pattern of ADHD persistence across the follow-up period. Among those who did not recover, most experienced either stable partial remission (15.6%) or fluctuating, waxing and waning ADHD symptoms (63.8%) from childhood to young adulthood. This finding echoes Lahey et al. (

30), who detected longitudinal symptom fluctuations in childhood ADHD that produced temporal instability in ADHD subtypes. Because our study was observational, we cannot draw definite conclusions about the causes of remission. However, we speculate about several possible sources of the waxing and waning symptom pattern. First, considering trait-state-error models of longitudinal data (

31), these fluctuations may reflect a combination of individuals’ genetic risks (i.e., traits), environmental factors (i.e., states), and measurement error. The high heritability of ADHD is well established (

32), and we speculate that genetic risks for ADHD may reflect a propensity for symptom expression that is dependent on environmental factors (e.g., changes in teachers, living arrangements, academic setting or level, type of employment, and relationships with employment supervisors, roommates, and significant others). For example, the MTA data set previously revealed that adolescents with ADHD display temporary ADHD symptom spikes at the middle school transition (

33). Measurement error, regression to the mean, and informant biases could contribute to apparent changes in symptoms and impairment. Nevertheless, the fluctuating patterns detected here reveal ADHD to be a dynamic rather than a static disorder. The extent to which environmental influences modulate symptom expression through neurobiological, basic cognitive, psychological, and behavioral mechanisms should be a future direction for research.

Our greatest limitation is that MTA follow-up was discontinued when participants were approximately 25 years of age. Therefore, it is not clear how longitudinal trends will continue into middle and older adulthood. Similarly, it is unclear whether the recovery pattern reflects permanent remission. The MTA sample only recruited participants with combined type ADHD, and the results may not generalize to other ADHD subtypes or presentations. The literature lacked any empirical precedent for the boundary between full and partial remission. In our effort to define these categories, we attempted to balance false positive and false negative classifications while considering known methodological pitfalls and symptom and impairment norms in the MTA sample; however, alternative definitions that were considered (see section S6 in the

online supplement) might have led to different estimates. Additionally, sensitivity analyses (see section S8 in the

online supplement) suggested that missing data may have produced an underestimate of the fluctuating pattern (by up to 10%) and that source switching may have had a very slight impact on diagnostic fluctuations. During childhood and adolescence, impairment ratings were available only from parents. Some adolescents may have met impairment criteria if teacher or self-ratings were available. Similarly, teacher ratings were of necessity discontinued in adulthood; some symptoms that were present in postsecondary academic settings may have gone undetected. The DISC was not administered at the 10-year assessment; thus, we could not review comorbidities in impaired but asymptomatic cases for this time point. Decisions made by the expert clinical panel were likely imperfect because panel members were unable to query differential diagnosis during real-time clinical assessment.

We used empirically validated, absolute cut-points for symptom and impairment thresholds. Although reflective of diagnostic nosology, using cut-points to categorize continuous data can lead to statistical error. Furthermore, we did not test relative remission thresholds (i.e., within-subject reductions in symptom count), thresholds that defined remission as the absence of symptoms according to any available informant, or combination rules that require all informants to substantiate the presence of an ADHD symptom (

34). Analyses to validate the definition of full remission should be replicated in larger, more diverse samples prior to clinical application. Requiring an informant to substantiate self-reports of remitted ADHD may have produced some false negative full remission classifications. Whereas we required absence of ADHD treatment as a criterion for full remission, some treated cases may have experienced remission that was independent of therapeutic intervention. Some impairments may have reflected residual effects of eliminated symptoms. Furthermore, some remission periods may have represented residual benefits of discontinued medication or behavioral treatments; the full relation between treatment and remission will be explored in a future MTA investigation. Future work should replicate our findings, characterize individuals who recover from ADHD, follow trajectories through older adulthood, and identify contributors to symptom fluctuations.