When dosed properly and administered as part of a comprehensive treatment plan, antipsychotic drugs can be remarkably effective in eliminating the positive symptoms of psychosis in patients with a first episode of nonaffective psychosis (

1). The second critically important use of these medications is to help prevent patients from experiencing relapses of acute psychosis (

2).

Elevated presynaptic dopamine is understood to be the pathway to a first episode of psychosis and is especially relevant to the acute state of illness (

3). Mechanisms include increased synthesis of dopamine, a greater likelihood of release with a stimulus such as amphetamine, and a higher level of intrasynaptic dopamine. Antipsychotic drugs occupy postsynaptic dopamine D

2 and D

3 receptors to diminish the effects of dopamine released from presynaptic terminals. After treatment of a first episode of psychosis with antipsychotic drugs for at least 1 year, there may be considerable heterogeneity in the effects of drug discontinuation on presynaptic dopamine terminals (

4). Patients with higher levels of dopamine synthesis prior to discontinuation were more prone to early relapse. Discontinuation of a dopamine antagonist ought to allow greater access for dopamine to presynaptic receptors, enabling feedback mechanisms to decrease presynaptic hyperactivity; these effects were missing in those who relapse. In contrast, patients who did not relapse in the first 12 weeks showed a reduction in presynaptic dopamine synthesis after discontinuation, consistent with an intact feedback mechanism.

Clinical features of treatment response in an acute episode and after discontinuation are consistent with these mechanisms. Amelioration of positive symptoms begins quickly and evolves to completion or a plateau over a period of weeks (

5). Relapse, and the response to treatment of relapses, is more heterogeneous (

6). The time course of relapse onset is not a mirror image of treatment response. After antipsychotic discontinuation, worsening of psychotic symptoms can occur over days; more commonly, relapse may not onset for many months after discontinuation. Once a relapse to acute psychosis occurs, the response to medication may take longer and be incomplete compared with the first episode (

6,

7).

The risk of return of symptoms after oral antipsychotic drugs are discontinued was described in studies carried out more than 60 years ago (

8). As well as initiating the still unresolved debate on how long antipsychotic drugs need to be continued after a first episode, these observations contributed to the rationale behind the development of long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations in 1963 (

9). Over the next decades, LAI antipsychotics were increasingly used for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia, although widespread geographic variation in practice occurred (

10). Development of oral dopamine-serotonin antagonist drugs provided a new treatment option with less risk of extrapyramidal side effects. Globally, the use of LAI dopamine antagonists then declined precipitously.

A combined systematic review and meta-analysis reported that the oral formulations of dopamine-serotonin antagonists were more effective than placebo in preventing relapse (risk difference=−0.33, 95% CI=−0.55 to −0.11) and were more effective than the older dopamine antagonists (haloperidol used in 10 of 11 studies, risk difference=−0.11, 95% CI=−0.15 to −0.07) (

11). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing oral against LAI antipsychotics showed no difference in protection against relapse (

12). However, the findings of meta-analytic studies comparing oral with LAI antipsychotics may be difficult to generalize to real-world settings. In randomized controlled trials, patients are monitored closely for adherence to medication, whether oral or injectable. In practice, patients receiving LAIs are commonly nonadherent to oral antipsychotics. In contrast to the meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, studies carried out with national databases, meta-analyses of cohorts, and expert opinions favor LAI antipsychotics over oral formulations for preventing relapse (

13 –

15). Comparison of oral and LAI antipsychotic does not answer another common clinical question—the risk of relapse after discontinuing antipsychotic medication. Inclusion of trials with placebo arms helps address this issue.

The report in this issue of the

Journal from Ostuzzi and colleagues provides an up-to-date analysis of LAI antipsychotics using a network meta-analysis technique (

16). This technique allows comparison of individual drugs against one another, and against placebo, by combining arms from independent randomized controlled trials. Other reports have used this analytic strategy to investigate antipsychotic efficacy. Here, there were two primary outcome measures: number of patients experiencing a study-defined relapse, and number of all-cause dropouts by trial end. The focus was on LAI antipsychotics in trials lasting 12 weeks or longer. Because just less than one-third of the trials included arms with oral antipsychotics, and just over 20% included placebo, comparisons of LAIs with these interventions were also possible.

A broad net was cast, retrieving studies from as long ago as 1968 and featuring 12 different types of LAIs and an aggregate number of 11,505 participants. Results are presented as network plots, along with tables with rankings for each drug. For the primary outcome of relapse, nine of 11 LAIs suitable for analysis were more effective than placebo in preventing relapse (zuclopenthixol and bromperidol being the exceptions). None of the newer LAIs differed from each other; the only head-to-head comparisons demonstrating differences showed paliperidone (3-month formulation), aripiprazole, and fluphenazine to be superior to haloperidol. For the primary outcome of all-cause dropouts, 10 of 12 LAIs available for analysis were more acceptable than placebo (perphenazine and bromperidol being the exceptions). In this analysis, aripiprazole was superior to bromperidol, fluphenazine, paliperidone (1-month formulation), pipothiazine, and risperidone.

In terms of strengths and weaknesses, this meta-analysis includes evaluation of an agent with a somewhat different pharmacology, the dopamine-serotonin partial agonist aripiprazole. Positive results are reported for aripiprazole LAI, particularly for the “acceptability” outcome evaluated through comparison of all-cause dropouts. The study included a series of sensitivity analyses, evaluating the extent of effects on outcomes of excluding trials that were not double blind, trials that used a placebo control, smaller trials carried out before 1990, and trials with a high risk of bias. Twenty-six supplements spanning 179 pages are available online for those wishing more detail. The authors are to be commended for a thorough discussion of eight limitations of their findings requiring consideration when results are applied to the clinical setting. One of these is the constraint placed on interpretations by including only randomized controlled trials. However, the authors also note that the findings of the network meta-analysis of LAIs are largely consistent with the performance of LAIs in a “real-world” effectiveness study involving a cohort of 29,823 patients, with rehospitalization or treatment failure as outcomes (

15). The latter study did not include data on aripiprazole LAI.

The large number of studies analyzed by Ostuzzi and colleagues share a common feature of patients who are stable on antipsychotic treatment at the trial onset followed by randomization to study arms that may include an LAI, an oral antipsychotic, or placebo. Not all trials included three types of arms, but the network meta-analysis approach allows the specific type and formulation of a drug (or placebo) in all analyzed arms to be compared one against another. The strongest conclusion was that maintenance treatment with LAIs is superior to placebo, with little difference between LAIs in magnitude of advantage over placebo or in head-to-head comparisons between LAIs. In any study, a portion of patients will relapse in an LAI treatment arm; the mechanism is poorly understood (

17). The meta-analysis findings confirm that a greater proportion will relapse in a placebo treatment arm, with a mechanism likely related to those described above. The comparison of these two types of arms, LAI maintenance and placebo maintenance, models the implications of a clinical decision in a patient stabilized on antipsychotic treatment to either continue treatment using an LAI or discontinue active antipsychotic medication.

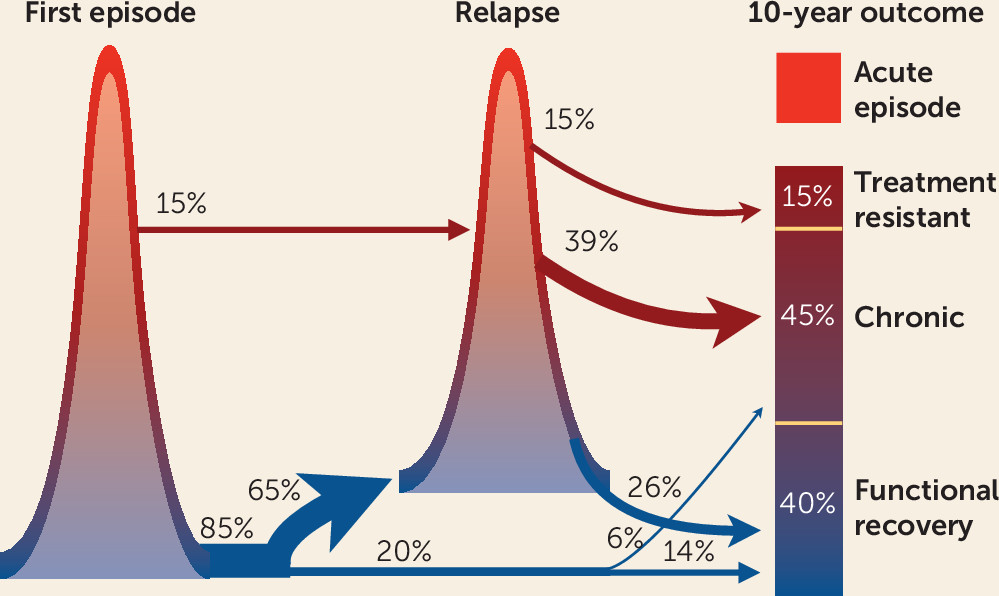

The report ends by identifying the need for studies to assess the value of LAIs in patients after a first episode of psychosis, rather than reserving this formulation for severe forms of illness. With the advent of well-tolerated LAIs, such a suggestion merits serious consideration. Studies of patients with an optimal response of positive symptoms in first-episode psychosis programs demonstrate the importance of preventing relapse to decrease risk for poor long-term outcomes such as treatment resistance (

18). An amalgam of treatment response in first-episode psychosis managed by early intervention teams, and a series of studies of 10-year outcomes of patients from first episodes of psychosis, provides a rationale, illustrated in

Figure 1. Full resolution of positive symptoms is the goal for first-episode psychosis, and although this is accomplished in a large majority of cases treated in early intervention programs, the relapse rate is also high, especially during the first 1–3 years. The acute state of a relapse is responsive to antipsychotic treatment. However, relapses appear to be part of the pathway to treatment resistance. Relapses of positive symptoms take longer to respond than during the first episode and are less likely to reach full resolution (

6,

7). Although the overall proportion of patients with treatment resistance may be lower in those optimally treated from onset, the total burden of illness remains high.

A trial assessing the maintenance of oral antipsychotic treatment after resolution of the acute phase showed continued protection against relapse for 3 years or longer (

2,

18). Studying LAIs optimized for acceptability, compared with oral antipsychotics and initiated soon after resolution of the acute phase, may represent the next step forward in improving long-term outcomes and preventing what can be the devastating consequences of nonaffective psychotic disorders in young patients.