Patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD) exhibit pathological personality traits (

1,

2). Alcohol misuse has been associated with heightened neuroticism and lower levels of conscientiousness, openness, extraversion, and agreeableness (

1–

5). Abnormal personality structure is theorized to underpin core symptoms of AUD and contribute to the treatment-resistant nature of the disorder (

6–

8). Studies have found that changes in personality traits correlate with changes in alcohol and substance use in non-AUD samples (

9–

11). Further, shifts in personality have also been found to predict long-term substance use behavior, suggesting tight correspondence between personality trait expression and behaviors related to alcohol use (

10,

11). Impulsiveness, a facet of the neuroticism factor, is a particularly strong predictor of alcohol consumption and negative drinking-related consequences (

3). Components of impulsiveness have been linked to quantity and frequency of alcohol use, hazardous drinking, alcohol dependence, alcohol-related problems, and family history of AUD (

12–

14). Overall, the personality profile of AUD is characterized by impairments in self-control and cognitive flexibility that are believed to promote the addictive cycle (

2,

9,

10). Coupled with the fact that baseline personality traits predict the efficacy of AUD treatments, there is a compelling rationale for developing interventions that seek to normalize susceptible phenotypes (

15).

Serotonergic psychedelics such as psilocybin (the active ingredient in magic mushrooms), lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and dimethyltryptamine (the psychoactive constituent of ayahuasca) exert their classical effects primarily via agonism at the 5-HT

2A receptor (

16). Clinical research examining the therapeutic potential of psychedelics has yielded encouraging results for the treatment of various mental health conditions (

17), including substance use disorders. A recent phase 2 clinical trial of psilocybin-assisted therapy (PAT) in AUD demonstrated rapid, robust, and enduring reductions in drinking behavior (

18). Despite progress in determining proximal biological targets and evaluating the clinical efficacy of classic psychedelics, the downstream psychological mechanisms leading from target engagement to clinical outcomes are poorly understood.

A growing body of evidence suggests that serotonergic psychedelics facilitate enduring shifts across multiple dimensions of personality relevant to mental health and addiction (

19). The five-factor model of personality—comprising neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness—has been used widely to investigate the effects of classic psychedelics on personality in both healthy volunteers and clinical populations. In healthy volunteers, increases in conscientiousness have been observed after psilocybin (

20), and increases in openness have been observed after psilocybin and LSD (

21,

22). In a small study of patients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (N=20), PAT was associated with increased openness and extraversion and decreased neuroticism (

23). However, the modulation of personality traits in major depression does not appear to be unique to psychedelic-assisted therapy (

24). Compared to conventional antidepressant treatment, some of psilocybin’s effects were numerically larger in magnitude, but not significantly greater, suggestive of a common therapeutic mechanism (

24). Of interest to AUD treatment, the effect size of PAT in patients with depression was largest for impulsiveness compared to other personality domains. Additionally, studies suggest that psychedelics may be more efficacious in individuals with patterns of personality traits associated with mental illness (

25,

26). For example, in one study, greater negative emotionality (analogous to neuroticism) and lower conscientiousness at pretreatment assessment were associated with larger personality trait changes, improvements in mental health, and reductions in alcohol use after participating in an ayahuasca ceremony (

25). Although studies have yet to investigate the effect of PAT on personality traits in the treatment of a substance use disorder, these findings provide a strong rationale for doing so.

Our aim in the present study was to address whether PAT precipitates personality changes using data from a double-blind randomized controlled trial of PAT for AUD (see Bogenschutz et al. [

18] for primary clinical outcomes). Given atypical personality structure in AUD and PAT-elicited alterations in personality among patients with major depressive disorder, we hypothesized that PAT in AUD patients would normalize personality trait expression (

5,

22,

24). Specifically, we hypothesized that PAT would elicit decreases in neuroticism and increases in extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness relative to placebo. Further, we anticipated that baseline personality traits would predict PAT-induced changes in personality traits (

25,

26). Finally, we hypothesized that decreases in impulsiveness would be associated with improvement in clinical status, in line with the predictive validity of impulse control in AUD (

3).

Methods

Participants and Treatment

Ninety-five adults with AUD were randomized to receive either psilocybin (N=49; 25 mg and 30–40 mg/kg) or active placebo (N=46; diphenhydramine, 50 mg and 100 mg), administered in two medication sessions 4 weeks apart in conjunction with 12 weeks of psychotherapy. In this multisite trial, participants received 4 weeks of preparation, underwent their first medication session, received 4 weeks of integration psychotherapy, underwent their second medication session, and then received their last 4 weeks of integration psychotherapy (weeks 0–12). Manualized therapy was provided at both sites as a male-female dyad therapy team. All therapists read the manuals and recorded simulated therapy sessions, which were then reviewed and rated by the fidelity monitor prior to working with study participants. In each therapy team, both therapists were trained in the treatment modalities, and at least one of the therapists was a licensed physician. Therapy utilized the preparation, support, and integration (PSI) model of psychedelic therapy and included alcohol-focused components that utilized principles from motivational enhancement therapy and action-oriented cognitive-behavioral therapy. One therapist was responsible for leading the alcohol-focused sessions and the other was responsible for the PSI sessions, but both therapists were trained in the delivery of these two intervention components. A detailed description of the sample, the CONSORT chart, the therapeutic paradigm, and the study timeline can be found in previous publications (

18,

27,

28). The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the two sites (New York University Grossman School of Medicine [NYU] and the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center [UNM]), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, the New Mexico Board of Pharmacy, and the New York State Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement. All participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental Design

Personality was assessed using the revised self-report NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R, Form S) at baseline (week 0; prior to the start of the 4 weeks of preparatory psychotherapy) and at the end of follow-up (week 36, 7 months after the second medication session) (

29). This validated 240-item instrument is based on the five-factor model of personality comprising neuroticism, extraversion, openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness. The five personality traits contain the following lower-order subscales, or facets: 1) neuroticism: anxiety, angry hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsiveness, and vulnerability; 2) extraversion: warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity, excitement-seeking, and positive emotions; 3) openness: fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, actions, ideas, and values; 4) conscientiousness: competence, order, dutifulness, achievement striving, self-discipline, and deliberation; and 5) agreeableness: trust, straightforwardness, altruism, modesty, and tender-mindedness. Personality traits in our AUD sample were numerically compared to a normative adult sample obtained from Costa and McCrae (

30) (N=1,000) to contextualize treatment-induced changes in personality.

Drinking-related behaviors were quantified using validated measures, as reported in the primary outcome paper for the study (

18). Alcohol consumption was measured using the Alcohol Timeline Followback (TLFB) at weeks 0, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 36. Alcohol use severity in the present study sample is characterized using dependence criteria and the number of years dependent, derived from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders; the total score from the Short Index of Problems (SIP); and baseline percent heavy drinking days, derived from the TLFB (

31–

33).

To limit the number of tests performed, the variable drinks per day (DpD) was selected because it is the only quantitative measure of mean alcoholic beverage consumption, is considered a clinically meaningful readout of AUD behaviors, and contains the other two drinking variables (percent heavy drinking days and percent drinking days) (

33,

34). Further, the psilocybin group demonstrated sustained reductions in DpD throughout an 8-month follow-up period relative to the placebo group (

18). DpD scores were calculated as pre- to posttreatment change scores (weeks 5–36 averaged minus weeks 0–4 averaged), and as an 8-month average following the first medication session (weeks 5–36 averaged), referred to hereafter as posttreatment drinking. World Health Organization (WHO) risk levels were used to categorize participants as low, moderate, high, or very high risk at week 4 (immediately prior to the first medication session) (

35). In line with previous research, WHO risk levels were defined in standard DpD as abstinent/low (males: 0–2.86; females: 0–1.43), moderate (males: 2.87–4.29; females 1.44–2.86), high (males: 4.30–7.14; females: 2.87–4.29), and very high (males: >7.14; females: >4.29) (

34).

Statistical Analysis

Of the original 95 participants who were randomized to treatment, two were not treated with study medication and nine did not complete pre- and posttreatment NEO questionnaires. Thus, 84 participants (psilocybin, N=44; placebo, N=40) were included in the analyses. Baseline treatment group differences were examined with respect to sex (assigned at birth), gender, age, weight, annual income, ethnicity, and baseline personality traits using independent-sample t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. For descriptive purposes, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed for pre- to posttreatment changes in DpD and posttreatment DpD. Group differences were not examined between randomized participants who did not receive study medication (N=2), those treated but for whom the study measures were incomplete (N=9), and those treated for whom complete measures were available (N=84) given unequal and small sample sizes. Baseline differences between the two samples from the NYU and UNM sites are provided in Table S3 in the online supplement.

Preplanned univariate analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were performed separately for each of the five personality traits: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Pre- to posttreatment change scores for each personality trait were entered as the dependent variable, treatment group as the between-subject factor, and baseline personality trait values as the covariate. Paired-sample t tests were used to probe within-group effects of time. In the psilocybin group, Pearson correlations explored relationships between baseline NEO values and pre- to posttreatment NEO change scores. Exploratory ANCOVAs were performed separately for males and females to evaluate effects of sex (assigned at birth) on personality trait changes.

Secondary paired-sample t tests examined pre- to posttreatment changes across the 30 personality facets to identify lower-order psychological constructs driving trait-level changes. Facet-level analyses were not restricted to traits showing treatment effects, with the aim of unmasking potential facet-level effects that would otherwise be undetected at the trait level. Finally, preplanned Pearson correlations examined relationships between changes in impulsiveness and pre- to posttreatment changes in drinking (DpD) and posttreatment DpD. Exploratory post hoc analyses probed relationships between impulsiveness and posttreatment alcohol use in those who continued to exhibit moderate-risk, high-risk, and very-high-risk levels of drinking immediately prior to the medication session, using WHO risk scores. False discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons was employed using the Benjamini-Hochberg method (

36) at the between-subject and within-subject level for the five personality trait tests, at the within-subject level for the six facets that comprise each trait, for the two drinking variables in the correlation analysis (posttreatment DpD and changes in DpD), and for the exploratory WHO risk subgroup analysis (three tests for moderate, high, and very high risk). Effect sizes are reported using Hedges’ g for within-group time effects and partial eta-squared for between-group effects. All analyses were performed with SPSS, version 22.0.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Participants reported being alcohol dependent for a mean of 31.56 years (SD=11.47), met a mean of 5.25 (SD=1.22) of the seven alcohol dependence criteria, had a mean SIP total score of 20.42 (SD=9.03), and had a mean of 52.57% (SD=30.32) heavy drinking days in the past month. The psilocybin and placebo groups were similar with respect to sex, gender, age, weight, annual income, and ethnicity at baseline (see Table S1 in the

online supplement). Assigned sex at birth and gender identification were identical and are therefore represented as a single variable in Table S1 in the

online supplement and elsewhere. Participants were predominantly white (∼77%) and affluent (mean income: psilocybin, $266.7K; placebo, $147.7K). See Bogenschutz et al. (

18) for additional demographic information about the treated sample. The two groups were similar with respect to neuroticism, extraversion, and agreeableness at baseline, but the psilocybin group was higher in conscientiousness and the placebo group was higher in openness at baseline (see Table S1 in the

online supplement). Exploratory analysis of site characteristics identified differences between the NYU and UNM samples with respect to ethnicity, baseline neuroticism and agreeableness, and baseline percent heavy drinking days and DpD (see Table S3 in the

online supplement).

For descriptive purposes, we provide information on the drinking variables used for the impulsiveness correlation analysis. One-way ANOVAs revealed a treatment effect (psilocybin vs. placebo) for pre- to posttreatment changes in DpD but not posttreatment DpD (see Table S1 in the online supplement). Psilocybin participants’ WHO risk scores at week 4 were characterized as follows: low, N=27; moderate, N=6; high, N=7; and very high, N=4. Placebo participants’ WHO risk scores at week 4 were characterized as follows: low, N=21; moderate, N=11; high, N=7; and very high, N=1.

Treatment Effects and Within-Group Time Effects on Personality Factors

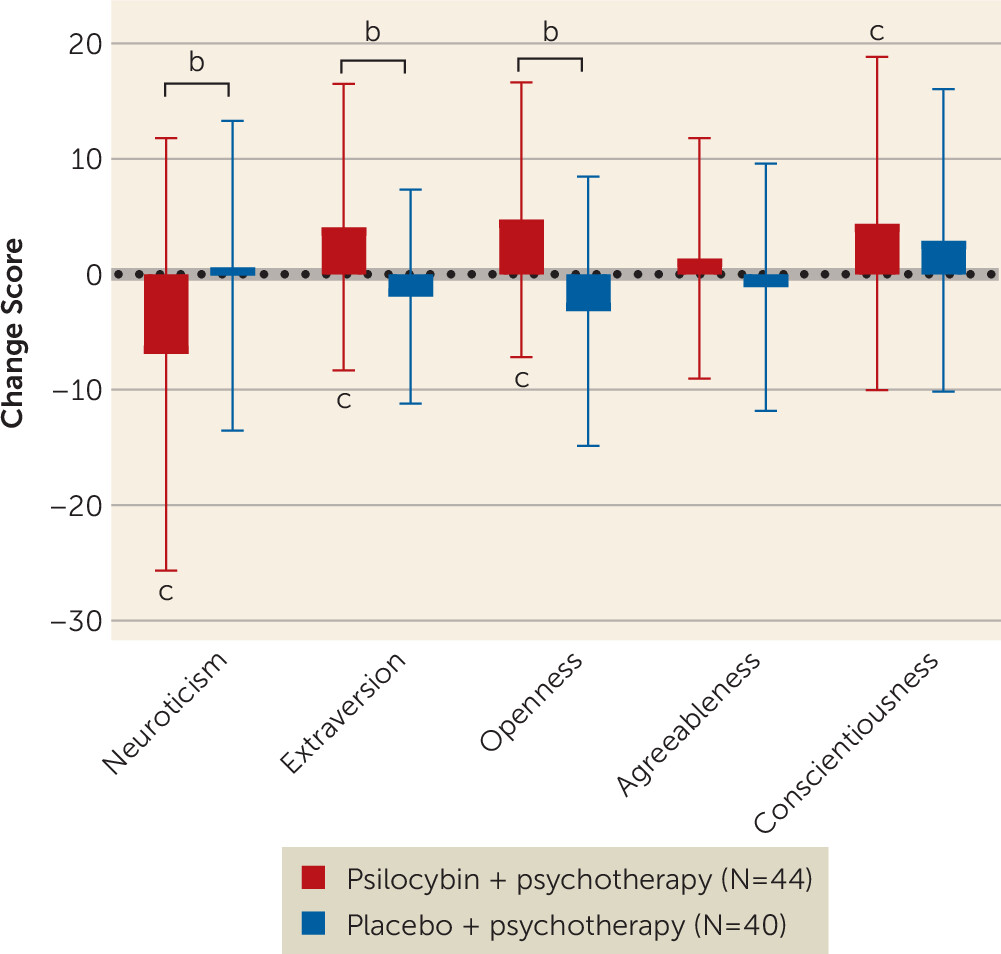

Relative to placebo plus psychotherapy, PAT was associated with significant decreases in neuroticism and increases in extraversion and openness, all of which survived FDR correction (

Figure 1,

Table 1). No significant treatment effects were observed for agreeableness or conscientiousness. Baseline covariates in the ANCOVA models were significant (p<0.05) for all personality traits except openness (F=2.29, df=1, 81, p=0.13). Within the psilocybin group, significant effects of time included decreases in neuroticism and increases in extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness, but not agreeableness (

Figure 1,

Table 1). After FDR correction, neuroticism, extraversion, and openness survived, but conscientiousness was no longer significant. Within the placebo group, effects of time were nonsignificant across all personality traits (

Figure 1; see also Table S2 in the

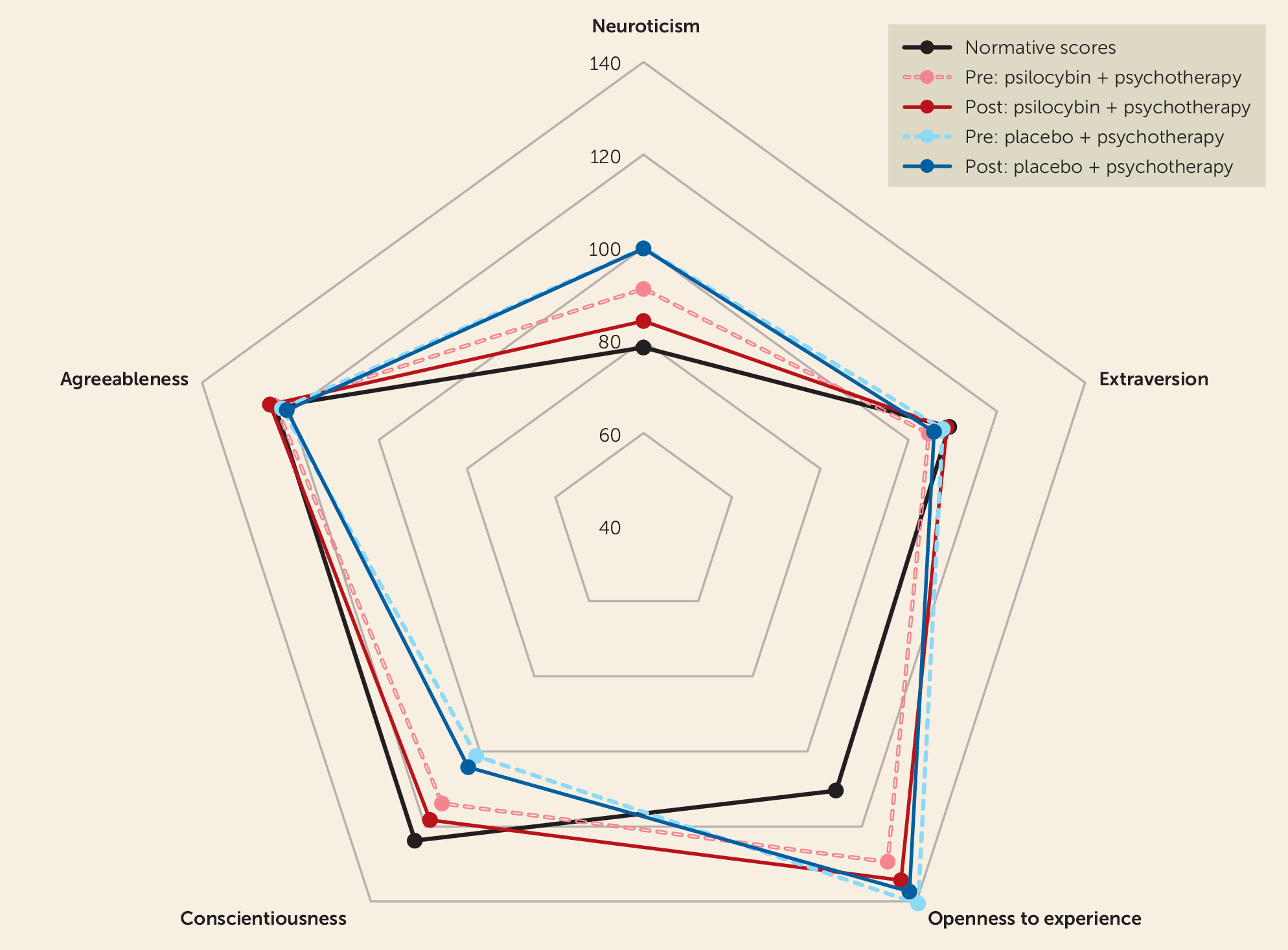

online supplement). Numerical comparisons with normative personality scores from Costa and McCrae (

30) revealed that personality trait changes in the psilocybin group were in the direction of normalization, except trait openness, which was above normative levels at baseline and further increased (

Figure 2,

Table 1). Within the psilocybin group, baseline personality traits significantly predicted changes in neuroticism (N=44; r=−0.32, df=42, p=0.03), extraversion (N=44; r=−0.52, df=42, p<0.001), and conscientiousness (N=44; r=−0.44, df=42, p<0.01), but not openness (N=44; r=0.03, df=42, p=0.87). Specifically, greater neuroticism was associated with greater reductions, and lower extraversion and conscientiousness were associated with greater increases.

Exploratory sex differences in treatment response were examined for the five personality traits. Females showed significant increases in conscientiousness (F=5.38, df=1, 32, p=0.027) and openness (F=8.49, df=1, 32, p=0.006), an increase in agreeableness that fell short of significance (F=3.99, df=1, 32, p=0.054), and nonsignificant changes in neuroticism (p=0.113) and extraversion (p=0.383). Males showed a significant increase in extraversion (F=5.10, df=1, 46, p=0.029) and nonsignificant changes in neuroticism (p=0.108), agreeableness (p=0.773), conscientiousness (p=0.609), and openness (p=0.189).

Psilocybin Effects of Time on Personality Facets

Secondary analysis included paired t tests to examine within-PAT-group changes in lower-order facets (

Table 2). Decreases in neuroticism were driven by significant decreases in depression, impulsiveness, and vulnerability, in the absence of significant changes in anxiety, angry hostility, or self-consciousness. Changes in depression, impulsiveness, and vulnerability survived correction for multiple comparisons (

Table 2). Increases in extraversion were driven by significant increases in positive emotions, in the absence of significant changes in warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity, or excitement. However, changes in positive emotion did not survive correction (

Table 2). Increases in openness were driven by significant increases in fantasy and feelings, in the absence of changes in aesthetics, actions, and ideas. Openness toward fantasy and feelings both survived correction (

Table 2). Increases in conscientiousness were driven by increases in deliberation, in the absence of changes in competence, dutifulness, achievement, self-discipline, and order. However, changes in deliberation did not survive correction. No significant changes in facets comprising the agreeableness factor were identified. Like the trait-level changes, changes in facets were in the direction of a normative sample, except for the openness facets fantasy and feelings (

Table 2). Exploratory facet analysis in the placebo group showed significant increases in the extraversion facet positive emotion and the openness facet values, but not any other facet (see Table S2 in the

online supplement). Openness to values survived correction (p

FDR<0.01), but positive emotion did not (p

FDR=0.12).

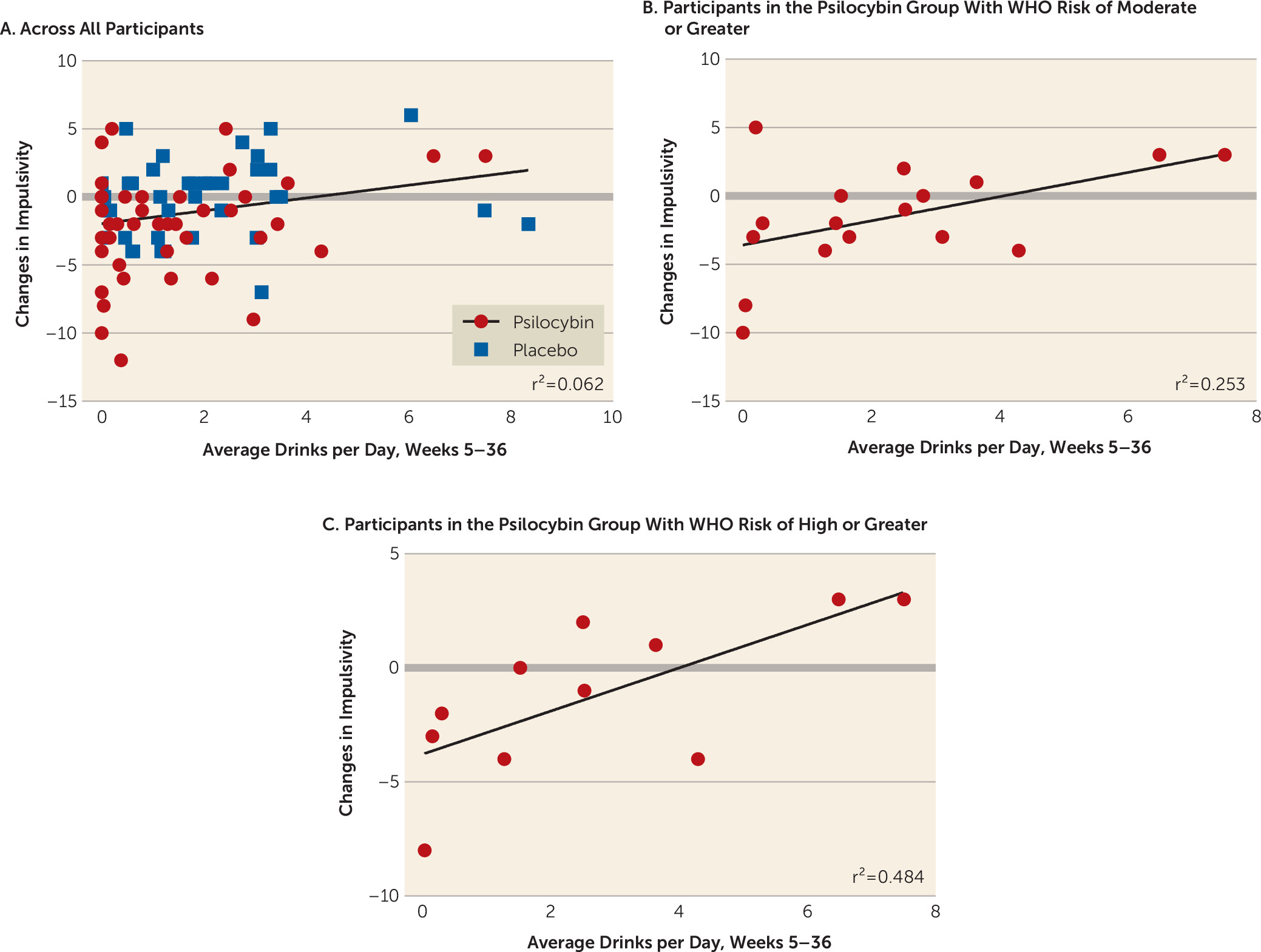

Relationships Between Changes in Impulsiveness and Drinking Behavior

Across all participants in both groups, decreases in impulsiveness were significantly correlated with lower posttreatment DpD (N=84; r=0.25, df=82, p=0.02, p

FDR=0.04) (

Figure 3A), but not with pre- to posttreatment changes in DpD (N=84; r=0.17, df=82, p=0.11). The relationship between changes in impulsiveness and posttreatment drinking survived correction for multiple comparisons (p

FDR=0.04). A post hoc correlation between changes in impulsiveness and posttreatment DpD was performed exclusively within the psilocybin group, given the null placebo group impulsiveness result, and was nonsignificant (N=44; r=0.27, df=42, p=0.07).

Since a subset of participants decreased their drinking to low WHO risk levels during the 4-week psychotherapy period preceding the first dose of psilocybin, we performed an exploratory subgroup analysis focused on participants in the psilocybin group who continued to exhibit at least moderate-risk levels of drinking immediately prior to the medication session. Among those with week-4 risk scores at or above the moderate risk level, we found a positive correlation between change in impulsiveness and posttreatment drinking behavior (N=17; r=0.50, df=15, p=0.04) (

Figure 3B). Further, when assessing only participants in the psilocybin group with baseline risk scores at or above the high risk level, a stronger relationship with impulsiveness emerged (N=11; r=0.70, df=9, p=0.02) (

Figure 3C); the correlation grew even larger, although it was nonsignificant, at the very high risk levels (N=4; r=0.91, df=2, p=0.09). However, the exploratory WHO risk subgroup analysis did not survive correction for multiple comparisons (p

FDR values of 0.06, 0.06, and 0.09, respectively).

Discussion

Personality Changes in Relation to Other Psilocybin Findings

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to report clinically relevant personality changes induced by PAT in the treatment of a substance use disorder—in this case, AUD. Relative to the active placebo plus psychotherapy, PAT was associated with reductions in neuroticism and increases in openness and extraversion. Post hoc within-group analyses confirmed that effects were driven by changes in the PAT group across these traits, and revealed increases in conscientiousness within the PAT group (although this did not survive correction). Except for trait openness, PAT-induced shifts in personality traits moved patients closer to general population norms, suggesting a general normalization effect.

Compared to previous studies of psychedelic-induced personality change, the facet-level analysis in this study adds granularity regarding lower-order personality constructs affected by PAT. The secondary facet-level findings in this study comprise PAT-induced reductions in depression, impulsiveness, and vulnerability (from the neuroticism factor); increases in positive emotions (from the extraversion factor); openness toward feelings and fantasy (from the openness factor); and deliberation (from the conscientiousness factor). However, only facets from the neuroticism and openness domains survived correction for multiple comparisons. We also found preliminary evidence that reductions in impulsiveness, a facet of the neuroticism factor, may be related to drinking outcomes after PAT.

The study findings are largely in agreement with a growing body of literature on psilocybin (and psychedelics more generally) altering core personality traits (

23–

25,

37). Studies with psilocybin have reported decreases in neuroticism, along with increases in extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness (

23,

24,

38,

39). Naturalistic ayahuasca studies have also reported enduring changes in all five personality traits (

40,

41), which were accompanied by decreases in depression, anxiety, and alcohol and drug use (

25). Notably, all but one of these study designs were open-label or observational, which limits the conclusions that can drawn, given the possible confounders of psychotherapy and elapsed time. There are considerable discrepancies in the patterns of personality changes between studies that may be attributable to differences in healthy versus clinical populations, sample sizes, therapeutic paradigms, and experimental designs. In a double-blind randomized controlled trial, Weiss et al. (

24) found that both psilocybin and escitalopram (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) elicited overlapping personality changes in major depressive disorder. However, the magnitude of effects on some personality traits were larger numerically after psilocybin. Baseline trait-level neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness predicted PAT-induced changes in personality, in line with findings from other psychedelic studies (

25,

26). Exploratory investigation into sex differences found that females showed increased trait levels of conscientiousness and openness, and men showed increased trait levels of extraversion, suggesting that males and females may respond differently to PAT. The present study marks the first randomized controlled trial to compare PAT with psychotherapy treatment using an active placebo. In general, the null findings in the placebo group suggest that, at least in this therapeutic formulation, psychotherapy alone does not significantly alter personality in AUD.

The personality changes precipitated by PAT were evident 7–8 months posttreatment, which is a robust finding given the brevity of the intervention. Because personality domains were not interrogated at other time points, several questions remain regarding the mechanisms and temporal dynamics of personality change. In the absence of interval assessments, it is not clear whether changes in personality precede, follow, or covary with reductions in drinking. Changes in personality domains may be maximal immediately after the psilocybin administration sessions, then plateau or diminish over time. Alternatively, the shifts might be catalyzed or augmented by the post-psilocybin integration therapy sessions and/or posttreatment reductions in drinking behavior. Future studies should examine personality across the entire treatment and follow-up period to gain insight into the temporal dynamics.

What Trait Changes Mean Clinically

The mechanisms through which psychedelics exert lasting impacts on various psychiatric conditions, including substance use disorders, remain an active area of inquiry. Certain personality traits convey elevated risk for problematic alcohol use (

42) and predict the onset and clinical course of alcohol use disorder (

43). Moreover, exposure to alcohol has been shown to alter the developmental trajectory of personality structure, particularly by stunting normative growth and maturation of traits (

43). Hicks and colleagues (

43) have postulated that chronic alcohol use leads to canalization, defined as “a narrowing of potential developmental trajectories that helps to maintain a deviant personality structure,” which underpins core AUD psychopathology. Within this framework, and consistent with preclinical findings that psychedelics may reopen critical periods of development (

44), PAT might catalyze or reactivate the maturation of personality domains that have been significantly affected by alcohol use. Whether personality changes are mediated by enhanced cognitive flexibility or alterations to attention is an interesting avenue for future research (

45). The patterns of personality changes observed in the present study also raise the possibility of using PAT as a preventive intervention for individuals with personality profiles that place them at high risk of developing AUD (

46).

In this study, we assessed the influence of PAT-induced decreases in impulsiveness on drinking outcomes. Impulsivity has long been tied to habitual behaviors (

47) and cognitive control deficiencies (

48), and is a treatment target in AUD (

49,

50). Across the full sample, decreases in impulsiveness correlated with lower drinking after the first medication session. Previous studies have reported improvements in behavioral control in AUD (

51) and reduced impulsiveness in patients with major depressive disorder after psilocybin treatment (

24), as well as reduced impulsiveness and alcohol and drug use after ayahuasca consumption in naturalistic settings (

25). Although our exploratory analysis did not survive correction for multiple comparisons, we found preliminary evidence that greater reductions in impulsiveness were associated with less alcohol consumption in a subset of PAT-treated individuals. This relationship was specific to AUD patients characterized as moderate and high risk immediately prior to receiving psilocybin. These findings hint that impulsiveness may play a larger role in at-risk individuals, and that other psychological mechanisms might underlie clinical improvements in individuals deemed lower risk or responsive to psychotherapy. Given the multifactorial etiology of addiction, our data imply that individual-specific psychological processes may underlie therapeutic improvement in AUD. Nonetheless, the impulsiveness findings are preliminary, and it is crucial for future research to explore the role of behavioral regulation in PAT outcomes.

Higher neuroticism and lower conscientiousness have been identified as key factors associated with increased risk of relapse in patients with AUD (

52). Consequently, interventions seeking to normalize these traits may confer resilience. Despite the fact that patients with substance use disorders are notoriously refractory to treatment-induced shifts in personality domains (

8), our study found that participants who exhibited greater baseline abnormalities in personality traits had larger shifts in the domains of neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness. This pattern mirrors observations in ayahuasca research, where initial personality traits have predicted subsequent trait changes, as well as reductions in depression, anxiety, and alcohol consumption (

25). Thus, even patients with substantially disordered personality structures may benefit from psychedelic-based treatments. Other studies investigating mental health interventions have reported positive correlations between certain personality domains and treatment response (

53,

54). Our findings suggest that PAT could serve as a valuable adjunct to conventional treatments for AUD and other psychiatric disorders. While these relationships warrant further exploration, it is conceivable that PAT-induced changes in specific personality domains may heighten awareness of maladaptive behaviors and bolster the therapeutic alliance, thereby enhancing patients’ receptivity to feedback and their ability to engage in other evidence-based psychotherapies (

55,

56).

Finally, our results may have implications for the treatment of psychiatric comorbidities in AUD and other psychiatric conditions characterized by atypical personality structure. AUD commonly co-occurs with other mental health disorders, including personality, mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders (

57). Symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders have been successfully treated with PAT, and they are associated with pathological personality structure similar to that observed in AUD, including higher degrees of neuroticism and disinhibition and lower degrees of conscientiousness and extraversion (

58,

59). Favorable mental health outcomes have been associated with lower neuroticism and greater extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness (

53), suggesting that it may be important to address personality in complex psychiatric presentations (

60,

61). While the present study excluded many patients with comorbid psychiatric conditions and other substance use disorders, our findings provide some support for studying more psychiatrically complex populations in future trials. Notwithstanding, close clinical supervision in controlled environments is necessary for ensuring safety, especially when investigating novel clinical populations, and for monitoring to ensure that psychedelics do not exacerbate atypical personality constellations.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it was a pilot study, and larger clinical trials are needed to confirm clinical significance. Next, although the personality instrument used here has been well validated and has high reliability (

62,

63), it relies on self-report. Self-reporting biases might be particularly elevated in psychedelic research due to issues with functional blinding. Indeed, approximately 94% of participants in the parent trial accurately guessed their treatment assignment (

18). Functional unblinding, combined with expectancy bias, may have shaped participants’ responses. For example, personality dispositions such as optimism/pessimism and anxiety have been shown to affect placebo and nocebo response (

64). However, most relevant to the present study, a study of PAT in patients with major depression found that expectancies did not mediate personality changes (

24), suggesting that their influence may be negligible in similar contexts.

It is also plausible that baseline group differences introduced systematic biases (e.g., ceiling effects) and influenced the detection of treatment and within-group time effects. At baseline, the psilocybin group exhibited higher conscientiousness and lower openness relative to the placebo group. In addition, both the placebo and psilocybin groups had very high openness scores (a mean of 140 for the placebo group and 129.5 for the psilocybin groups, relative to a normative score of 110.5). Higher conscientiousness in the psilocybin group may have decreased sensitivity to detecting treatment effects in conscientiousness (ceiling effect). Furthermore, treatment effects on openness could be a result of regression to the mean, or ceiling effects in the placebo group. This concern was mitigated but not eliminated by including baseline personality traits as covariates.

Another limitation is the fact that personality was measured at only two time points, thereby limiting inferences about temporal dynamics and causal mechanisms of change. It is possible that some of the changes in personality were a consequence of decreased drinking during follow-up. Also, without an assessment immediately prior to the administration of the medication, we cannot rule out the possibility that personality changes occurred during the 4 weeks of preparatory therapy. However, the absence of personality changes in the placebo group suggests that this may not be the case, unless the personality changes had waned by the week-36 assessment.

The generalizability of these findings is limited by the relatively small, homogeneous sample (i.e., mean annual incomes >$140,000, and 77% white) and by the lack of the psychiatric comorbidities that are frequently seen in AUD populations. Additionally, the samples at the NYU and UNM sites were significantly different with regard to ethnicity, baseline neuroticism and agreeableness, and baseline drinking behavior. However, the influence of these factors on outcomes cannot be determined given the small UNM sample (N=10). Sample sizes for the correlations of impulsiveness with drinking outcomes were especially small for the moderate- and high-risk samples (N=17 and N=11, respectively) and should be interpreted with caution. The sample also had high baseline levels of trait openness compared to normative and AUD samples. This may reflect a unique feature of individuals seeking psychedelic or novel experimental treatments, of recruiting from highly urban geographical areas, or some combination of these and/or other factors (

65).

Conclusions

This is the first double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to characterize PAT-induced alterations in personality structure in AUD. Treatment with PAT, but not placebo plus psychotherapy, attenuated personality trait abnormalities in this AUD study sample, evidencing a normalization effect. Patterns of personality changes were characterized by decreases in neuroticism and increases in extraversion and openness, congruent with improved mental health. Secondary analyses of lower-order personality constructs implicate depression, impulsiveness, vulnerability, openness to feelings, and openness to fantasy. Associations between decreases in impulsiveness and lower posttreatment alcohol consumption offer a putative psychological mechanism for symptom improvement. Additional PAT studies are needed to clarify the relationships between personality changes and AUD symptoms, identify their neurobiological substrates, and determine whether they generalize to other clinical populations.