Bipolar disorder is a severe, often debilitating mental illness affecting approximately 2% of the general population worldwide (

1). Individuals with bipolar disorder can experience manic, depressive, and mixed episodes throughout their course of illness, which may or may not include psychotic symptoms (

2,

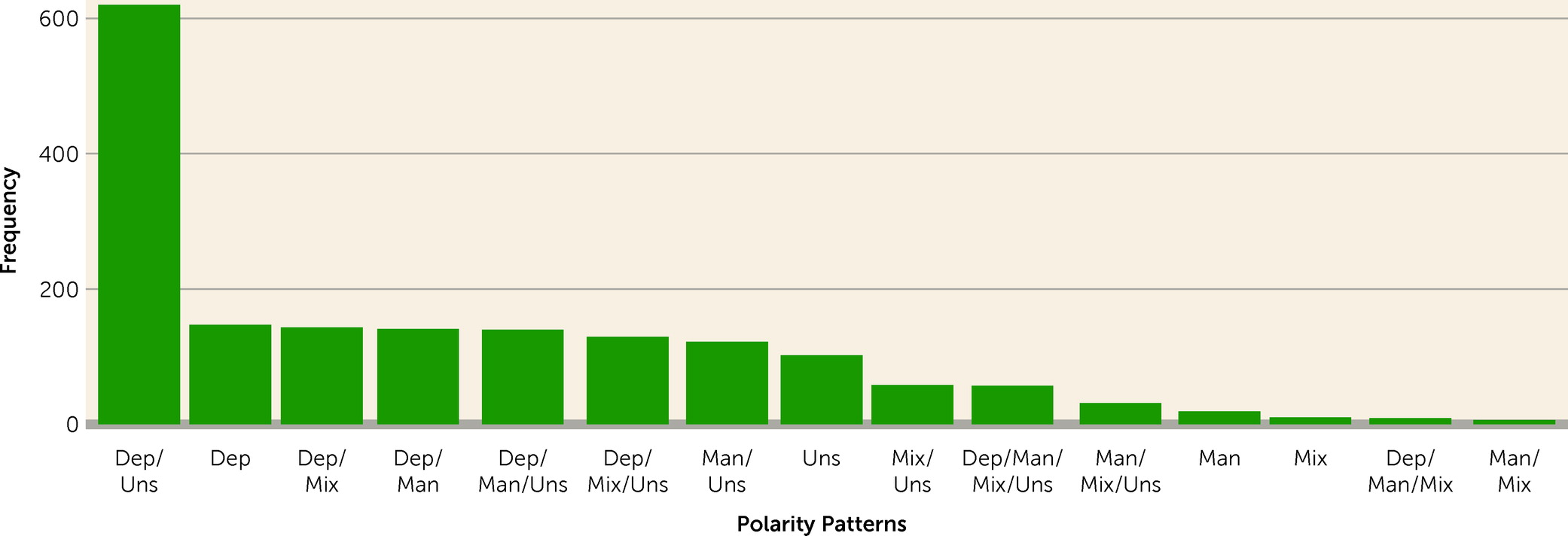

3). Presenting an excess of one or more of these types of episodes is not uncommon, as it occurs in approximately half of all those with bipolar disorder (

4). Most studies of polarity suggest that having more depressive episodes is the most prevalent phenotypic presentation (

5,

6), but having more manic episodes is also common (

7,

8). Episode polarity has been studied extensively and has been found to be associated with a wide variety of clinical outcomes, making it of interest as a phenotypic marker in the treatment of bipolar disorder (

4).

Genetic factors account for a considerable proportion of the population-level variation in bipolar disorder (

9), and previous studies have demonstrated shared genetic liability between bipolar disorder and other mental disorders, including major depressive disorder and schizophrenia (

10,

11). Recently, polygenic risk scores (PRSs)—a weighted sum of genetic risk variants associated with a disorder or trait (

12)—have been shown to be associated with clinically relevant outcomes such as progression to bipolar disorder in individuals with major depression (

13), bipolar disorder subtypes (type I vs. type II) (

14), psychosis in bipolar disorder (

15), and response to lithium treatment (

16). These findings support the idea that polarity in bipolar disorder may also in part be genetically determined.

Since the prognosis and ideal treatment varies for different episode polarities (

17), information on predictors of phenotypic presentation, potentially including genetics, in bipolar disorder could aid clinicians in making more individualized treatment decisions (

18). Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the degree to which polygenic liabilities for bipolar disorder, major depression, and schizophrenia, measured using PRSs, are associated with episode polarity in individuals with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, we examined whether PRSs are associated with psychotic symptoms in the context of different episode polarities.

Discussion

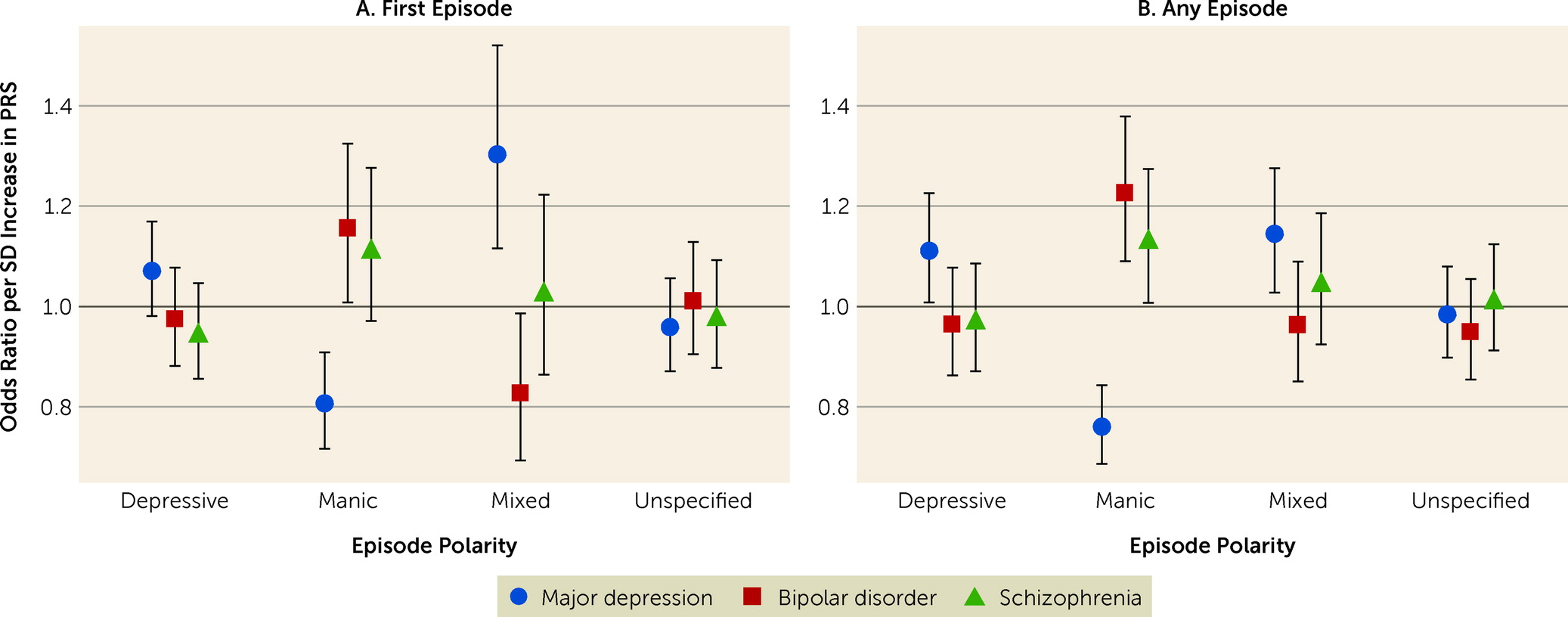

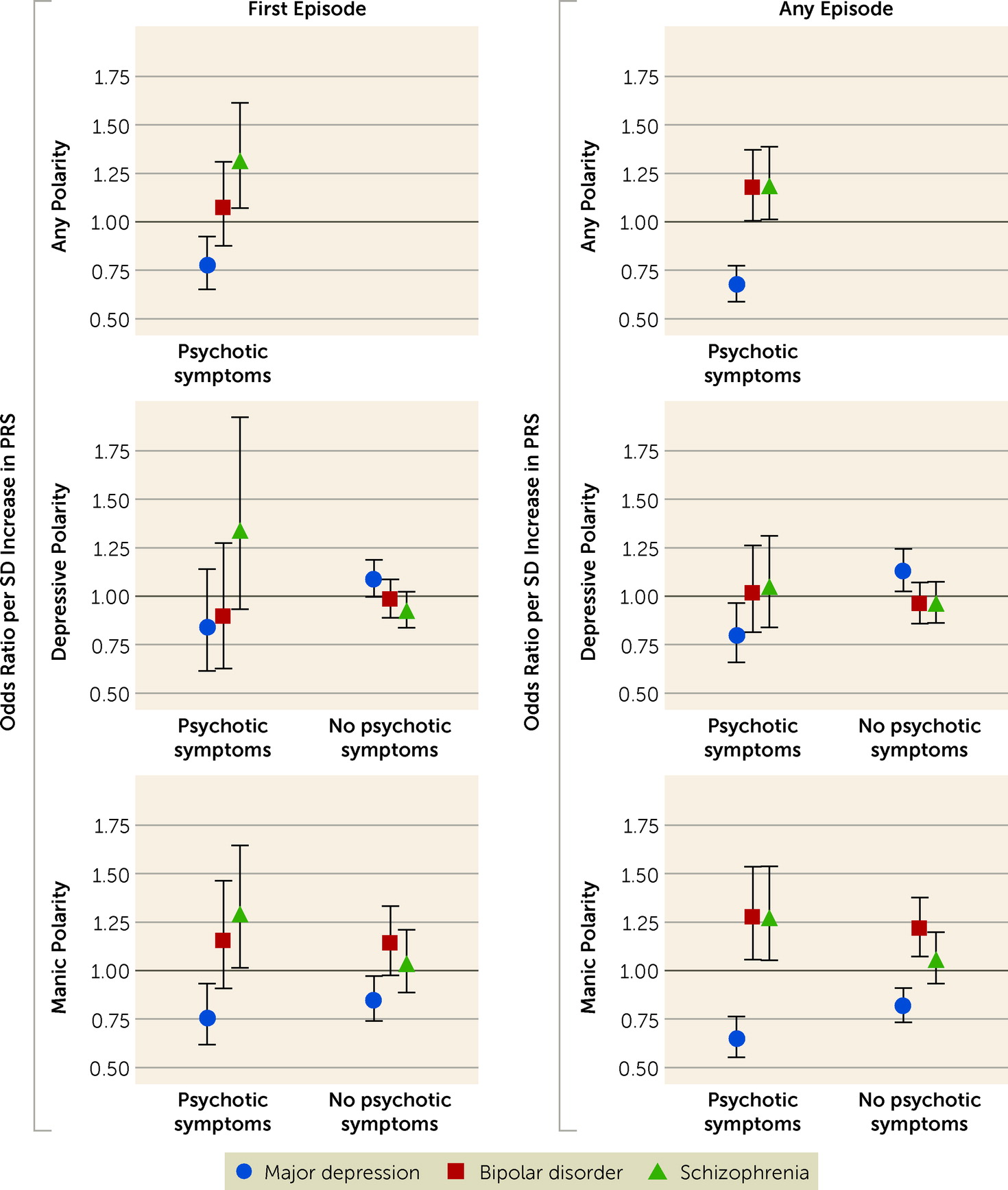

In this study, we examined whether polygenic liabilities for bipolar disorder, major depression, and schizophrenia are associated with episode polarity and psychotic symptoms in individuals with bipolar disorder. The results show that polygenic liability for bipolar disorder was positively associated with manic polarity, while polygenic liability for depression was positively associated with depressive and mixed polarities and negatively associated with manic polarity. Polygenic liability for schizophrenia was positively associated with manic polarity, but only when psychotic symptoms were present. These findings suggest that episode polarity and psychotic symptoms in individuals with bipolar disorder are, at least in part, genetically determined, and provide further evidence that phenotypic heterogeneity in bipolar disorder is related to underlying genetic heterogeneity.

Previous studies identified positive correlations between PRSs for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia and psychotic symptoms in bipolar disorder (

34,

35). This could suggest that polygenic liabilities for both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia drive the psychotic phenotype to some degree, which is consistent with the findings of a study by Musliner et al. (

13), who report that having high polygenic liability for both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia aligned with the greatest risk of developing affective psychosis in patients with unipolar depression. It is also consistent with findings from the Bipolar Disorder Working Group of the PGC (

36), who showed that psychotic symptoms were associated with high bipolar disorder PRS and schizophrenia PRS, while manic symptoms were only associated with bipolar disorder PRS. Although still preliminary, these findings add to a growing body of evidence, including family studies assessing parental psychotic and affective disorders as risk factors for these same disorders in offspring, suggesting that both the affective and the psychotic genetic components play a role in the phenotypical presentation and time of onset of affective disorders (

13,

37–

39). The findings could, however, also be related to the large symptom overlap between psychotic and affective disorders (

40), and to the fact that some individuals in our sample will go on to develop a schizophrenia spectrum disorder later in life (

41).

Our findings indicate that patients with bipolar disorder who have higher polygenic liability for depression are significantly less likely to experience psychotic symptoms in either depressive or manic episodes. This suggests that psychotic depression may be more genetically similar to bipolar disorder or schizophrenia than to nonpsychotic depression—an interpretation supported by previous research showing that a parental history of bipolar disorder was a risk factor for psychotic depression but not for nonpsychotic depression (

37). This idea that psychotic depression may be a somewhat separate genetic entity from more common phenotypic presentations of depression (i.e., nonpsychotic) (

42) is also supported by findings from Coombes et al. (

43), who showed that individuals with bipolar disorder who had an increased polygenic score for anhedonia (a core symptom of depression) were less likely to have a history of psychotic symptoms.

We found that the polygenic liability for depression was positively associated with mixed episodes, which often have severe symptoms and poor clinical outcomes (

44). Interestingly, pharmacological treatment of mixed episodes is more similar to treatments of mania and psychosis than to treatments of depression (

45), and yet our findings suggest that mixed episodes may be more similar genetically to major depression than to bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Additional research is needed to explore this somewhat unexpected finding further. Finally, none of the three PRSs showed any type of association with episodes of unspecified polarity. This makes intuitive sense, as unspecified polarity likely represents a mix of the specified polarities (depression, mania, and mixed), possibly of less severity. The unspecified polarity category alone is therefore of limited interest. However, the lack of association between the three PRSs and episodes of unspecified polarity does indirectly support the validity of the associations between PRSs and the congruent episode polarities.

The results of this study suggest that PRSs may be useful in the prediction of the clinical course of bipolar disorder. Since optimal treatment differs for different types of episodes in the context of bipolar disorder (

17,

46), we hypothesize that PRSs may also play a future role in more personalized treatment choices (

18). Moreover, new evidence suggests that information on PRSs may also be of benefit for patients in other ways. A recent study by Putt et al. (

47) found that access to information on PRSs was associated with improved awareness of symptoms, decreased stigma, and improved treatment adherence among patients with bipolar disorder.

Our study has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, our sample did not include individuals with bipolar disorder who were treated solely by general practitioners or private-practice psychiatrists, as these practitioners do not report data to the DCPRR. However, since bipolar disorder is a fairly severe mental illness and psychiatric hospital treatment in Denmark is free (tax-funded), the proportion of individuals who are untreated or treated only by general practitioners or private-practice psychiatrists in Denmark can be assumed to be relatively small. Nevertheless, the patients in the iPSYCH2015 cohort likely represent the more severely ill fraction, and the reported associations between polygenic liability and episode polarity may therefore not be representative of bipolar disorder in general.

Second and relatedly, any episode of bipolar disorder that is not severe enough to have led to hospital contact is not registered in the DCPRR. This will likely have affected the validity of the outcomes of our study—namely, the first registered episode of bipolar disorder, any episode of a given polarity, and the number of episodes of a given polarity—as none of these include episodes that did not lead to hospital contacts. It can be argued that they should therefore rather be referred to as the first registered severe episode of bipolar disorder, any severe episode of a given polarity, and the number of severe episodes of a given polarity. Despite this “severity bias,” we would argue that the results remain of interest from both an etiological and a clinical perspective.

Third, we could not examine differences between patients with bipolar I and bipolar II disorders, as diagnoses in the registers are based on ICD-10, which does not explicitly distinguish between bipolar I and II disorders. Fourth, as data on symptom levels over time are not available in the registers, we were unable to investigate the relationship between the three PRSs and symptom levels in bipolar disorder. If such data had been available, and if the PRSs had had a better fit to the symptom data compared with the polarity data, it would have offered further support for the dimensional (diagnostic) approach to bipolar disorder. It can be argued, however, that our finding of psychotic mania (as opposed to nonpsychotic mania) driving the association between the PRS for schizophrenia and manic polarity already offers some support for the dimensional model.

Fifth, all individuals in the sample were between 10 and 35 years old when they had their first episode of bipolar disorder. Hence, some of these individuals may go on to develop a disorder in the schizophrenia spectrum later in life (

41), which may drive some of the association between the schizophrenia PRS and psychotic mania. Sixth, the predictive accuracy of the polygenic scores is affected by both the training data sets and the method used to train the scores. In this study we followed the approach of Albiñana et al. (

28) and used a combination of the PGC GWAS summary statistics and iPSYCH individual-level data (using cross-validation) as training data. Using other methods and training data would lead to different results, and potentially also to different conclusions. Relatedly, as the results from larger GWASs become available, it is likely that the prediction of episode polarity and psychosis in bipolar disorder will improve.

The present study also has numerous strengths. iPSYCH2015 is currently one of the largest and most comprehensive samples for studying the genetics of mental disorders (

20). Furthermore, the population-based sampling approach of iPSYCH2015 minimizes selection bias and increases generalizability to broader populations. The study also uses validated (

48), clinician-derived diagnoses as the outcome, which is particularly relevant for interpreting the potential of PRSs in a real-world clinical context. Lastly, since the iPSYCH2015 sample is mostly of Danish or European ancestry, it reduces the possibility of confounding by population stratification.

In summary, PRSs for bipolar disorder, major depression, and schizophrenia were found to be positively associated with episode polarity and psychotic symptoms in individuals with bipolar disorder in a congruent manner. These findings provide preliminary evidence that episode polarity and psychotic symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder are partly genetically determined. Although PRSs are not yet ready to be applied in clinical practice, the performance of PRSs is expected to improve as larger GWAS discovery data sets and improved calculation methods become available.