Books published by American Psychiatric Association Publishing represent the findings, conclusions, and views of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the policies and opinions of American Psychiatric Association Publishing or the American Psychiatric Association.

Names: Summergrad, Paul, editor. | Silbersweig, David, editor. | Muskin, Philip R., editor. | Querques, John, 1970– editor. | American Psychiatric Association Publishing, issuing body.

Title: Textbook of medical psychiatry / edited by Paul Summergrad, David A. Silbersweig, Philip R. Muskin, John Querques.

Description: First edition. | Washington, DC : American Psychiatric Association Publishing, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “The Textbook of Medical Psychiatry focuses on medical disorders that can directly cause or affect the clinical presentation and course of psychiatric disorders. Clinicians who work primarily in psychiatric settings, as well as those who practice in medical settings but who have patients with co-occurring medical and psychiatric illnesses or symptoms, can benefit from a careful consideration of the medical causes of psychiatric illnesses. The editors, authorities in the field, have taken great care both in selecting the book’s contributors, who are content and clinical experts, and in structuring the book for maximum learning and usefulness. The first section presents a review of approaches to diagnosis, including medical, neurological, imaging, and laboratory examination and testing. The second section provides a tour of medical disorders that can cause psychiatric symptoms or disorders, organized by medical disease category. The third section adopts the same format as the second, offering a review of psychiatric disorders that can be caused or exacerbated by medical disorders, organized by psychiatric disorder types. The final section contains chapters on conditions that fall at the boundary between medicine and psychiatry. Even veteran clinicians may find it challenging to diagnose and treat patients who have co-occurring medical and psychiatric disorders or symptoms. The comprehensive knowledge base and clinical wisdom contained in the Textbook of Medical Psychiatry makes it the go-to resource for evaluating and managing these difficult cases”—Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019055530 (print) | LCCN 2019055531 (ebook) | ISBN 9781615370801 (hardcover ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781615372829 (ebook)

Classification: LCC RC467 (print) | LCC RC467 (ebook) | NLM WM 140 | DDC 616.89—dc23

A CIP record is available from the British Library.

David A. Silbersweig

Philip R. Muskin

Contents

Contributors

Foreword

Professor Sir Simon Wessely

Introduction: The Importance of Medical—Psychiatric Illness

Paul Summergrad, M.D.

David A. Silbersweig, M.D.

Philip R. Muskin, M.D., M.A.

John Querques, M.D.

Part I

Approach to the Patient

1 An Internist’s Approach to the Neuropsychiatric Patient

Joseph Rencic, M.D.

Deeb Salem, M.D.

2 The Neurological Examination for Neuropsychiatric Assessment

Sheldon Benjamin, M.D.

Margo D. Lauterbach, M.D.

3 The Bedside Cognitive Examination in Medical Psychiatry

Sean P. Glass, M.D.

4 Neuroimaging, Electroencephalography, and Lumbar Puncture in Medical Psychiatry

Daniel Talmasov, M.D.

Joshua P. Klein, M.D., Ph.D.

5 Toxicological Exposures and Nutritional Deficiencies in the Psychiatric Patient

Mira Zein, M.D., M.P.H.

Sharmin Khan, M.D.

Jaswinder Legha, M.D., M.P.H.

Lloyd Wasserman, M.D.

Part II

Psychiatric Considerations in Medical Disorders

6 Cardiovascular Disease

Peter A. Shapiro, M.D.

7 Endocrine Disorders and Their Psychiatric Manifestations

Jane P. Gagliardi, M.D., M.H.S., FACP, DFAPA

8 Inflammatory Diseases and Their Psychiatric Manifestations

Rolando L. Gonzalez, M.D.

Charles B. Nemeroff, M.D., Ph.D.

9 Infectious Diseases and Their Psychiatric Manifestations

Oliver Freudenreich, M.D.

Kevin M. Donnelly-Boylen, M.D.

Rajesh T. Gandhi, M.D.

10 Gastroenterological Disease in Patients With Psychiatric Disorders

Ash Nadkarni, M.D.

David A. Silbersweig, M.D.

11 Renal Disease in Patients With Psychiatric Illness

Lily Chan, M.D.

J. Michael Bostwick, M.D.

12 Neurological Conditions and Their Psychiatric Manifestations

Barry S. Fogel, M.D.

Gaston C. Baslet, M.D.

Laura T. Safar, M.D.

Geoffrey S. Raynor, M.D.

David A. Silbersweig, M.D.

13 Cancer: Psychiatric Care of the Oncology Patient

Carlos G. Fernandez-Robles, M.D., M.B.A.

Sean P. Glass, M.D.

14 Dermatology: Psychiatric Considerations in the Medical Setting

Katherine Taylor, M.D.

Janna Gordon-Elliott, M.D.

Philip R. Muskin, M.D., M.A.

15 Women’s Mental Health and Reproductive Psychiatry

Marcela Almeida, M.D.

Kara Brown, M.D.

Leena Mittal, M.D.

Margo Nathan, M.D.

Hadine Joffe, M.D., M.Sc.

Part III

Medical Considerations in Psychiatric Disorders

16 Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Aaron Hauptman, M.D.

Sheldon Benjamin, M.D.

17 Psychotic Disorders Due to Medical Illnesses

Hannah E. Brown, M.D.

Shibani Mukerji, M.D., Ph.D.

Oliver Freudenreich, M.D.

18 Catatonia in the Medically Ill Patient

Scott R. Beach, M.D.

Gregory L. Fricchione, M.D.

19 Mood Disorders Due to Medical Illnesses

Sivan Mauer, M.D., M.S.

John Querques, M.D.

Paul Summergrad, M.D.

20 Anxiety and Related Disorders: Manifestations in the General Medical Setting

Charles Hebert, M.D.

David Banayan, M.D., M.Sc., FRCPC

Fernando Espi-Forcen, M.D., Ph.D.

Kathryn Perticone, A.P.N., M.S.W.

Sameera Guttikonda, M.D.

Mark Pollack, M.D.

21 Substance Use Disorders in the Medical Setting

Samata R. Sharma, M.D.

Saria El Haddad, M.D.

Joji Suzuki, M.D.

22 Neurocognitive Disorders

Flannery Merideth, M.D.

Ipsit V. Vahia, M.D.

Dilip V. Jeste, M.D.

Part IV

Conditions and Syndromes at the Medical-Psychiatric Boundary

23 Chronic Pain

Robert M. McCarron, D.O.

Samir J. Sheth, M.D.

Charles De Mesa, D.O., M.P.H.

Michelle Burke Parish, Ph.D., M.A.

24 Insomnia

Karl Doghramji, M.D.

25 Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders

Anna L. Dickerman, M.D.

Philip R. Muskin, M.D., M.A.

Index

Contributors

Marcela Almeida, M.D.

Instructor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School; Attending Physician, Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

David Banayan, M.D., M.Sc., FRCPC

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

Gaston C. Baslet, M.D.

Director, Division of Neuropsychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Scott R. Beach, M.D.

Program Director, MGH/McLean Adult Psychiatry Residency, Massachusetts General Hospital; Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Sheldon Benjamin, M.D.

Interim Chair of Psychiatry, Director of Neuropsychiatry, and Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, Massachusetts

J. Michael Bostwick, M.D.

Professor of Psychiatry, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota

Hannah E. Brown, M.D.

Director, Wellness and Recovery After Psychosis Program, Boston Medical Center; Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts

Kara Brown, M.D.

Attending Psychiatrist, Veterans Affairs, New Orleans, Louisiana

Michelle Burke Parish, Ph.D., M.A.

Director of Research, Train New Trainers Primary Care Psychiatry Fellowship, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California, Davis, California

Lily Chan, M.D.

Psychiatry Resident, Cambridge Health Alliance/Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Charles De Mesa, D.O., M.P.H.

Associate Professor and Director, Pain Medicine Fellowship, Division of Pain Medicine, University of California, Davis School of Medicine, Davis, California

Anna L. Dickerman, M.D.

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, and Chief, Psychiatry Consultation-Liaison Service, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, New York

Karl Doghramji, M.D.

Professor of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Medicine; Medical Director, Jefferson Sleep Disorders Center; and Program Director, Fellowship in Sleep Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Kevin M. Donnelly-Boylen, M.D.

Associate Director, Psychiatric Consultation and Liaison Service, Boston Medical Center; Instructor of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts

Saria El Haddad, M.D.

Director of Partial Hospitalization, Dual Diagnosis, Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Fernando Espi-Forcen, M.D., Ph.D.

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

Carlos G. Fernandez-Robles, M.D., M.B.A.

Clinical Director, Center for Psychiatric Oncology and Behavioral Sciences; Associate Director, Somatic Therapies Service; and Psychiatrist, The Avery D. Weisman, M.D., Psychiatry Consultation Service, Massachusetts General Hospital; Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Barry S. Fogel, M.D.

Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neurologist and Senior Psychiatrist, Center for Brain/Mind Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Oliver Freudenreich, M.D.

Co-Director, MGH Schizophrenia Clinical and Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital; and Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Gregory L. Fricchione, M.D.

Director, Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital; Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Jane P. Gagliardi, M.D., M.H.S., FACP, DFAPA

Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Associate Professor of Medicine, Vice Chair for Education, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, and Interim Director, Combined Residency Training Program in Internal Medicine–Psychiatry, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina

Rajesh T. Gandhi, M.D.

Director, HIV Clinical Services and Education, Massachusetts General Hospital; and Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Sean P. Glass, M.D.

Psychiatrist, Northwest Permanente, Portland, Oregon

Rolando L. Gonzalez, M.D.

Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin

Janna Gordon-Elliott, M.D.

Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, New York

Sameera Guttikonda, M.D.

Chair, Consultation-Liaison Division, Department of Psychiatry, John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital, Cook County Health, Department of Psychiatry, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

Aaron Hauptman, M.D.

Instructor of Psychiatry, Boston Children’s Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Charles Hebert, M.D.

Chief, Section of Psychiatry and Medicine; Director, Psychiatric Consultation Liaison Service; Associate Professor of Internal Medicine and of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

Dilip V. Jeste, M.D.

Senior Associate Dean for Healthy Aging and Senior Care; Estelle and Edgar Levi Memorial Chair in Aging, University of California, San Diego

Hadine Joffe, M.D., M.Sc.

Executive Director, Mary Horrigan Connors Center for Women’s Health and Gender Biology; Paula A. Johnson Associate Professor of Psychiatry in the Field of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School; Vice Chair for Research, Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; and Director of Psycho-Oncology Research, Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts

Sharmin Khan, M.D.

Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, New York University Langone Health, New York, New York

Joshua P. Klein, M.D., Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Neurology and Radiology, Harvard Medical School, and Vice Chair for Clinical Affairs, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Margo D. Lauterbach, M.D.

Director, Concussion Clinic, Neuropsychiatry Program, Sheppard Pratt Health System, Baltimore, Maryland

Jaswinder Legha, M.D., M.P.H.

Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, New York University Langone Health, New York, New York

Sivan Mauer, M.D., M.S.

Clinical Instructor, Psychiatry, Tufts University School of Medicine, Mood Disorders Program, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts

Robert M. McCarron, D.O.

Professor and Vice Chair, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, and Co-Director, Train New Trainers Primary Care Psychiatry Fellowship, University of California, Irvine School of Medicine, Irvine, California

Flannery Merideth, M.D.

Clinical Fellow, Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Leena Mittal, M.D.

Instructor in Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School; Attending Psychiatrist, Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Shibani Mukerji, M.D., Ph.D.

Associate Director, Neuro-Infectious Disease Unit; and Assistant Professor in Neurology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Philip R. Muskin, M.D., M.A.

Professor of Psychiatry and Senior Consultant in Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, New York

Ash Nadkarni, M.D.

Instructor, Harvard Medical School; Associate Psychiatrist and Director, Digital Integrated Care, Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Margo Nathan, M.D.

Instructor in Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Charles B. Nemeroff, M.D., Ph.D.

Professor and Acting Chair of Psychiatry; Associate Chair for Research, Mulva Clinic for the Neurosciences; Director, Institute of Early Life Adversity Research; Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin

Kathryn Perticone, A.P.N., M.S.W.

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

Mark Pollack, M.D.

Grainger Professor and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

John Querques, M.D.

Vice Chairman for Hospital Services, Department of Psychiatry, Tufts Medical Center; Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts

Geoffrey S. Raynor, M.D.

Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Neurology Fellow, Division of Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Joseph Rencic, M.D.

Associate Professor, Department of Medicine; Director of Clinical Reasoning Education, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts

Laura T. Safar, M.D.

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School; Associate Neuropsychiatrist, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; Director, MS Neuropsychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Center for Brain/Mind Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts

Deeb Salem, M.D.

Physician-in-Chief, Department of Medicine; Sheldon M. Wolff Professor and Chairman, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts

Peter A. Shapiro, M.D.

Professor of Psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons; Director, Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry Service, New York–Presbyterian Hospital, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York

Samata R. Sharma, M.D.

Director of Addiction Consult Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Samir J. Sheth, M.D.

Assistant Professor, Pain Medicine, Director of Neuromodulation, and Director of Student and Resident Training, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, University of California, Davis School of Medicine, Davis, California

David A. Silbersweig, M.D.

Stanley Cobb Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry, and Co-Director, Center for the Neurosciences, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Paul Summergrad, M.D.

Dr. Frances S. Arkin Professor and Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry, and Professor of Psychiatry and Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine; and Psychiatrist-in-Chief, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts

Joji Suzuki, M.D.

Director, Division of Addiction Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Daniel Talmasov, M.D.

Resident in Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; and Resident in Neurology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, New York

Katherine Taylor, M.D.

Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry, New York University (NYU) School of Medicine, NYU Langone Health Perlmutter Cancer Center, New York, New York

Ipsit V. Vahia, M.D.

Medical Director, Geriatric Psychiatry Outpatient Programs, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts

Lloyd Wasserman, M.D.

Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, New York University Langone Health, New York, New York

Professor Sir Simon Wessely, M.A., B.M., B.Ch., M.Sc., M.D., FRCP, FRCPsych, FMedSci

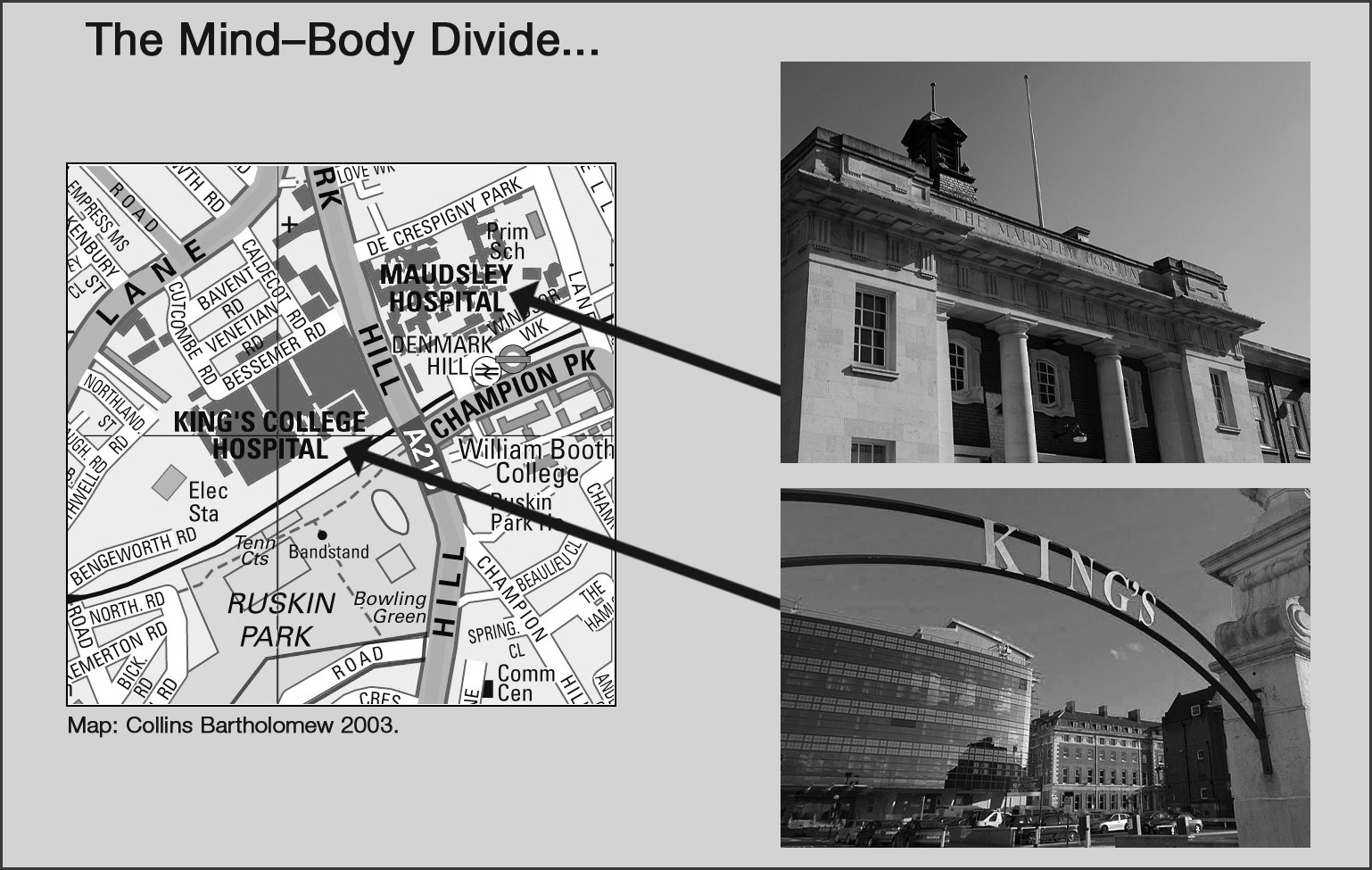

Regius Professor of Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London; President, Royal Society of Medicine; Past President, Royal College of Psychiatrists

Mira Zein, M.D., M.P.H.

Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, California

Disclosure of Interests

The following contributors to this textbook have indicated a financial interest in or other affiliation with a commercial supporter, manufacturer of a commercial product, and/or provider of a commercial service as listed below:

Margo D. Lauterbach, M.D. Equity Interest: One-third owner of Brain Educators LLC, publishers of The Brain Card®.

Charles B. Nemeroff, M.D., Ph.D. Research Grants: National Institutes of Health (NIH), Stanley Medical Research Institute; Consultant: Bracket (Clintara), Fortress Biotech, Gerson Lehrman Group (GLG) Healthcare and Biomedical Council, Janssen Research and Development LLC, Magstim Inc, Prismic Pharmaceuticals, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc, Taisho Pharmaceutical Inc, Takeda, Total Pain Solutions (TPS), and Xhale; Stock Holdings: Abbvie, OPKO Health Inc, Antares, Bracket Intermediate Holding Corp, Celgene, Network Life Sciences Inc, Seattle Genetics, and Xhale; Scientific Advisory Board: American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP), Anxiety Disorders Association of America (ADAA), Bracket (Clintara), Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (BBRF) (formerly named National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression [NARSAD]), Laureate Institute for Brain Research Inc, RiverMend Health LLC, Skyland Trail, and Xhale; Board of Directors: ADAA, AFSP, and Gratitude America; Income or Equity ($10,000 or more): American Psychiatric Publishing, Bracket (Clintara), CME Outfitters, Takeda, and Xhale; Patents: U.S. 6,375,990B1 (method and devices for transdermal delivery of lithium) and U.S. 7,148,027B2 (method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy via transport inhibition of monoamine neurotransmitters by ex vivo assay).

Peter A. Shapiro, M.D. Dr. Shapiro affirms that he has no financial conflicts of interest to disclose. Supported in part by the Nathaniel Wharton Fund, New York.

Paul Summergrad, M.D. Nonpromotional Speaking: CME Outfitters Inc, Lundbeck Foundation; Consultant: Compass Pathways, Mental Health Data Services, Pear Therapeutics; Stock or Stock Options: Karuna Therapeutics, Mental Health Data Services, Pear Therapeutics, Quartet Health; Royalties: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, Harvard University Press, Springer Publishing Company.

The following contributors stated that they had no competing interests during the year preceding manuscript submission:

Rolando L. Gonzalez, M.D.; Janna Gordon-Elliott, M.D.; Philip R. Muskin, M.D., M.A.; John Querques, M.D.; Joseph Rencic, M.D.; Peter A. Shapiro, M.D.; David A. Silbersweig, M.D.; Joji Suzuki, M.D.