Case Vignette: Susan is a 38-year-old married female who presents at 5 weeks postpartum with symptoms of sadness, anxiety, insomnia, decreased appetite, low energy, and guilt. Her symptoms began 9 days after the delivery of her fourth child, a healthy baby girl. Despite the fact that the baby sleeps for 3- to 4-hour stretches, Susan is unable to sleep and has persistent, ruminative thoughts about the health and well-being of the baby. She has a supportive husband, an 8-year-old son, and two daughters, ages 6 and 4. Susan's mood was fine during the pregnancy, and she has no prior history of postpartum or pregnancy-related depression. She did have a prior episode of major depression in her late 20s, when she had moved across the country to be with her husband. She was treated with paroxetine for a few months, with resolution of her depression. She has a mother with a history of major depressive disorder. She is breast-feeding her baby 100% of the time.

The risk of developing a major depressive disorder is twice as high for women as for men, with rates of up to 20% (

1–

3), and an onset often during the childbearing years. The postpartum period is a time of particularly increased vulnerability (

4), with prevalence rates of 13%–19% within the first 3 months after delivery (

5–

7). An early study by Kendell et al. (

8) found a sevenfold increased rate of psychiatric admission within the first postpartum month compared with the prepregnancy rate. For a variety of reasons, however, postpartum disorders are underrecognized and therefore undertreated. Pregnant women are often not educated about the possibility of postpartum psychiatric illness, and symptoms may go unrecognized by obstetricians and pediatricians. Some women are told that their symptoms are consistent for the postdelivery period and will resolve with time. Women often feel guilt and shame for having negative emotions at a time when they “should” be joyful and consequently do not seek professional help.

In contrast to postpartum depression, 50%–80% of new mothers experience postpartum blues (

9) with symptoms that include tearfulness, anxiety, irritability, emotional lability, and sleep disturbance. Symptoms generally begin 3–4 days after delivery, peak between days 5 and 7, and resolve by day 12 (

10). Stressful life events, interpersonal difficulties, work-related difficulties, and an infant with health problems can increase the risk for postpartum blues (

11). Prior history of depression, family history of depression, depressive symptoms during pregnancy, and premenstrual dysphoria also increase the risk for postpartum blues, suggesting that this condition may be within the spectrum of mood disorders (

11). Most cases of postpartum blues resolve by day 12 after delivery, without any ongoing sequelae. Treatment of postpartum blues includes reassurance, validation, and assistance in caring for the mother, the baby, and the home. However, 20% of women proceed to development of postpartum depression, and thus symptoms should be monitored for persistence or worsening severity (

12).

Untreated maternal psychiatric illness can rapidly escalate and potentially place mother and child at significant risk, affect maternal-child bonding, disrupt the family environment, and have a negative impact on the child's development over the short and long term. Thus, early recognition of postpartum psychiatric illness is essential. Although the DSM-IV defines the postpartum interval as the first 4 weeks following childbirth, in reality patients frequently present for treatment after the first postnatal month and up to a year after delivery (

13).

Symptoms of postpartum depression

Postpartum depression is the most common psychiatric illness that occurs in the puerperium. Estimates for the rate of postpartum depression vary from 10% to 15% (

14,

15) to as high as 30% (

4). Symptoms are consistent with those of a major depressive episode and include a depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, for at least 2 weeks and/or loss of interest or pleasure in activities one used to enjoy. Other symptoms include fatigue, feeling restless or slowed down, a sense of guilt or worthlessness, difficulty concentrating, insomnia, and recurring thoughts of death or suicide. In addition, women with postpartum depression often have marked anxiety and a tendency to ruminate or even obsess over the health and well-being of the baby. Some women may experience disturbing aggressive obsessional thoughts, although they have no intention of harming the baby (

16). In women with very severe postpartum depression, psychotic symptoms including hallucinations or delusions may develop.

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale is a useful, self-rated screening tool that can lead to an early identification of symptoms (

17,

18). A score of 12 or greater indicates the likelihood of depression but not severity. Although scores cannot be interpreted as diagnostic, they can indicate the need for further evaluation.

Risk factors for postpartum depression

Prior psychiatric history, family psychiatric history, psychosocial factors, and hormonal factors have all been implicated in the development of postpartum depression (

19,

20). Without a prior psychiatric history, the risk of developing a postpartum depression is 10%. With a history of major depression, the risk for postpartum depression increases to 25%, and with a history of prior postpartum depression, the risk increases to 50% (

21,

22). Depression during pregnancy (

11), unmarried status, unplanned pregnancy (

23), marital conflict, bereavement, and preterm birth (

24) have also been found to increase the risk of postpartum depression. Primiparity has been associated with an increased risk for early-onset (within 4 weeks) postpartum depression, whereas both younger and advanced age have been associated with later onset (5–12 weeks postpartum) depression (

25). Viguera et al. (

4) found that younger age at illness onset, bipolar disorder, and high lifetime occurrence rates were strongly associated with depression in the postpartum period. Because the time of onset of postpartum disorders varies, with some illnesses having an early onset within several days after delivery and others arising later at 6–12 weeks after delivery, researchers have speculated that hormone changes and/or biological factors may be etiologically related to early-onset postpartum illness, whereas psychosocial stressors may have greater influence on the development of later onset illness.

Biological factors

Because of the dramatic and sudden hormonal shifts that occur at the time of childbirth, postpartum disorders have been etiologically linked to these reproductive changes. Women with a history of premenstrual symptoms are at a higher risk for postpartum depression, suggesting a possible oversensitivity to hormonal shifts (

10). In some women with postpartum depression, the onset can correspond to hormonal events such as weaning or the return of menses (

26,

27). Bloch et al. (

28) administered pregnancy level doses of estrogen and progesterone to euthymic women with and without a history of postpartum depression. Women with a history of postpartum depression were more likely to develop depressive symptoms upon withdrawal of hormonal treatment, compared with those without a history of postpartum depression, suggesting a differential sensitivity to the mood-destabilizing effects of gonadal steroids. Some early studies have shown a reduction in postpartum depressive symptoms with estrogen supplementation (

19–

31).

Although thyroid dysfunction has not been consistently found in women with postpartum psychiatric disorders, there may be a subgroup of women for whom thyroid pathology plays a role (

32–

35). Hypothyroidism occurs in 10% of postpartum women, with a peak incidence at 4–6 months after delivery (

36). Thus, the evaluation of women presenting with postpartum depression should include an assessment of thyroid function.

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) may play a role in postpartum depression. Brain cell membranes contain a phospholipid bilayer, and abnormalities in phospholipid polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) composition may be etiologically significant in depression (

37,

38). Changes in such composition affect membrane microstructure and may also influence neurotransmitter function (

39). Edwards et al. (

40) found a significant depletion of red blood cell membrane omega-3 PUFAs in depressed subjects, and a cross-national comparison by Hibbeln (

41) reported a correlation between high rates of fish consumption, a dietary source of omega-3 PUFAs, and a lower annual prevalence of major depression. Maternal levels of the long-chain PUFA docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) have been reported to be reduced after the second trimester of pregnancy (

42), presumably due to an increased need by the developing fetus. Omega-3 fatty acids are necessary for optimal neurodevelopment in utero, and with the progressively increased fetal demands, reduced maternal essential fatty acid stores (

43,

44) may not be replenished until 26 weeks postpartum (

45). Hibbeln (

46) found that lower seafood consumption and lower DHA content in maternal breast milk were associated with higher rates of postpartum depression across countries. Although a pilot study (

47) found a reduction in depressive symptoms of postpartum depression with treatment with DHA and the long-chain PUFA eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) over 8 weeks, double-blind placebo-controlled studies have not found that EPA combined with DHA or DHA alone has been beneficial in the prevention of postpartum depression (

48,

49).

Other studies looking at the role of neurotransmitter systems (

50), the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (

51), and immune systems have suggested the possibility of lower synaptic serotonin levels (

52), alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (

53) including elevated midpregnancy placental corticotrophin-releasing hormone levels (

54), and a mixed proinflammatory immune response (

55) in postpartum depression (

56). Sacher et al. (

50) found significantly elevated monoamine oxidase-A binding on positron emission tomography scanning throughout the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulated cortex, anterior temporal cortex, thalamus, dorsal putamen, hippocampus, and midbrain in the early postpartum period, suggesting a monoamine-lowering process related to estrogen removal that could be associated with sad mood and vulnerability to postpartum depression.

Impact on the infant

Untreated maternal depression can have significant effects on the development of the child and compromise maternal-infant bonding. In videotaped interactions of mothers with new-onset depression, women demonstrate less responsiveness to their baby's social signals. At 3 months postpartum, these mothers, compared with nondepressed mothers, are more likely to express indifference or upset feelings toward their babies. At 9 months of age, babies of depressed mothers perform less well on developmental tasks. Stein et al. (

57) found that 19-month-old infants of depressed mothers were less mutually responsive and harmonious than those of nondepressed mothers. In observations of mother-infant play interactions, these same babies were less likely to respond with positive affect to mothers and showed more anger than control babies, even after the mothers recovered. Three-year-old children of postnatally depressed women have been shown to have behavioral problems, and 4-year-old children have shown significant cognitive deficits (

58). Poobalan et al. (

59) reviewed eight randomized controlled trials of treatment of mothers with postnatal depression. Maternal-infant relationships improved with treatment in all studies, and cognitive development of the child improved in one study with intensive prolonged maternal therapy. In addition to impaired development, children of depressed mothers may themselves be at risk of depression (

21,

60,

61).

Treatment

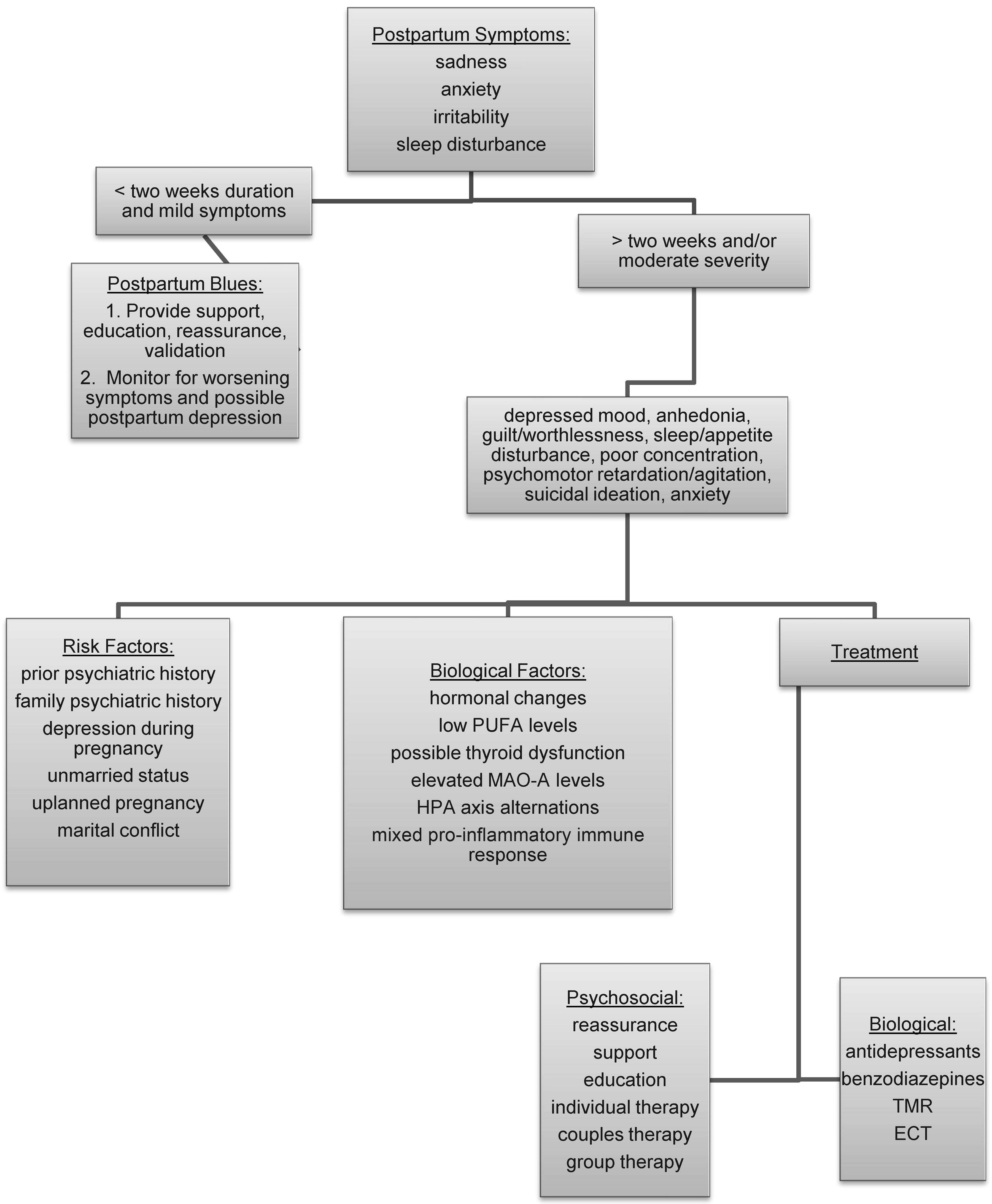

A treatment approach for postpartum depression should include consideration of multiple modalities including reassurance and support, education, individual and group psychotherapy, and psychopharmacology (

Figure 1). Couples therapy may be part of the treatment plan if there is discord in the relationship. Even without difficulty in the relationship, one or two meetings with the couple can be useful for providing information and support for the mother and her partner. A useful suggestion is for increased help around the home, which will allow the mother to obtain adequate rest and care for herself. Referrals to self-help groups and national organizations, including Postpartum Support International and Depression After Delivery may allow access to additional resources.

As with any mood disorder, untreated episodes may become more severe and difficult to treat over time. A number of open-label studies have shown a benefit of antidepressants, including sertraline (

62), paroxetine (

63), bupropion (

64), venlafaxine (

65), and fluvoxamine (

66), for postpartum depression. In a double-blind comparison of sertraline and nortriptyline for the treatment of postpartum depression, both medications had comparable response and remission rates, with 46%–48% remitting and 56%–69% responding by 8 weeks of treatment (

67). A small placebo-controlled trial of paroxetine treatment for postpartum depression found greater improvement in clinical severity and higher remission rates for the paroxetine group compared with the control group (

68). For women with marked anxiety in addition to depression, the short-term use of benzodiazepines can be helpful. If hospitalization is indicated and the mother's condition is stable, attempts should be made to maintain the mother-infant relationship by encouraging visits between mother and baby.

Symptoms of postpartum depression must be distinguished from those of postpartum psychosis, a rare but severe psychiatric illness that affects 1–2 women per 1,000 births. Symptom onset of psychosis is often early and rapid and includes mood lability, depersonalization, confusion, disorientation, agitation, bizarre behavior, delusions, paranoia, hallucinations, and sleep disturbance. Early detection, assessment, and monitoring are crucial because suicide or infanticide is a serious, although rare (1 in 50,000) outcome. For women with postpartum psychosis, hospitalization is often necessary.

Because the risk of postpartum depression is higher in women with a history of major depression (

69) or postpartum depression (

70), some women may consider prophylaxis at the time of delivery. In a study of 23 pregnant women with a history of at least one previous postpartum depression, those who chose symptom monitoring had a recurrence rate of 62.5% compared with 6.7% for those who chose symptom monitoring in combination with pharmacotherapy (

15). Wisner et al. (

71), however, did not find that treatment with nortriptyline (N=26) was any more effective than placebo (N=25) in the prevention of postpartum major depression for women with a history of a prior postpartum depressive episode.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation may be an option for women who are reluctant to take antidepressants because of side effects or concerns about infant exposure through nursing (

72,

73). A study by Garcia et al. (

72) found a remission of depression, defined by a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score <10, in eight of nine patients after a 4 week course of transcranial magnetic stimulation. Electroconvulsive therapy may be considered for severe cases of depression that involve suicidality or psychotic symptoms and for cases in which maternal or infant health is compromised or the condition is refractory to psychopharmacology (

74).

In some cases, oral contraceptives can exacerbate depressive symptoms. For these women, other methods of birth control may need to be considered.

Breast-feeding

With a heightened vulnerability to psychiatric illness in the postpartum period, breast-feeding mothers may require psychotropic treatment. The American Academy of Pediatrics regards breast milk as the optimal source of nutrition for infants during the first 6 months of life (

75). The decision of whether or not to administer psychotropic medications to a breast-feeding mother is therefore based on a number of factors: 1) the known benefits of nursing to mother and infant; 2) the wishes of the mother regarding nursing; and 3) an assessment and understanding of the limited information regarding the safety of medication in an exposed breast-fed baby.

Before the baby has been exposed to medication via breast milk (even if exposure has occurred during pregnancy), a thorough pediatric assessment should be made to determine the infant's baseline clinical status. Level of alertness, behavior, and sleep and feeding patterns should be assessed. Doses of medication should be kept as low as possible to maintain psychiatric stability in the mother while reducing exposure to the infant. In all cases, ongoing clinical monitoring of the infant is essential. Infant exposure may also be minimized by supplementing nursing with bottle-feeding (

76). Most psychotropic medications pass readily into breast milk (

13). However, studies in general have not found high rates of adverse events in infants exposed to antidepressants, including tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (

48,

76–

79). Most reports have found low or undetectable infant plasma levels for sertraline, paroxetine, and nortriptyline. In a pooled analysis of antidepressants levels, Weissman et al. (

80) found elevated infant levels with fluoxetine and a limited number of cases of citalopram exposure. The authors point out that plasma levels or even brain tissue levels may not accurately predict the biochemical effect of antidepressants on the brain, and thus low or even undetectable infant plasma concentrations alone cannot assure that the antidepressant has no effect on the rapidly developing brain. Although rates of adverse events are low, serum concentrations of antidepressants in the infant can vary widely and the long-term outcome of infants exposed during breast-feeding is unknown (

48,

77,

78). For most antidepressants, infant medication exposure is generally higher through placental passage in pregnancy than through breast milk, and thus if a woman has been treated with a particular medication during pregnancy, continuation of treatment during breast-feeding can minimize the number of medications to which an infant has been exposed (

13).

Conclusions

The postpartum period is a time of increased vulnerability for depression, particularly for women with a prior history of mood disorders. Symptoms may begin days to weeks, or even months, after delivery. Early recognition and treatment are essential for both the well-being of the mother and the baby. Treatment approaches need to be multimodel, taking into account support, education, psychotherapy, and possible pharmacotherapy. The role of breast-feeding may also influence treatment decisions for women. Although the etiology of postpartum depression has not been clearly delineated, psychosocial and biological factors seem to contribute. Further research to identify specific psychosocial risk factors is warranted. Not all women with psychosocial risk factors develop postpartum depression. Therefore, further understanding of potential biological mechanisms can also help in the prevention, identification, and early treatment of postpartum depression and optimize the welfare of both mother and child.