We assessed effect sizes for target problems, psychiatric symptoms, personality functioning, social functioning and overall outcome. As outcome measures of target problems, we included both patient ratings of target problems and measures referring to the symptoms specific to the patient group under study (e.g. measures of depression in treatment studies of major depressive disorder or a measure of impulsivity for studies examining borderline personality disorder).

29 For psychiatric symptoms we included both broad measures of psychiatric symptoms such as the Symptom Check List 90 (SCL-90) and specific measures such as measures of depression or anxiety.

30 For the assessment of personality functioning, measures of personality characteristics were included (e.g. the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory).

31 Social functioning was assessed using the Social Adjustment Scale and similar measures.

32 Whenever a study reported multiple measures for one of the areas of functioning (e.g. target psychiatric symptoms), we assessed the effect size for each measure separately and calculated the mean effect size of these measures within each study. In our previous meta-analysis outcome measures were assigned either to target problems or to psychiatric symptoms, personality functioning or social functioning.

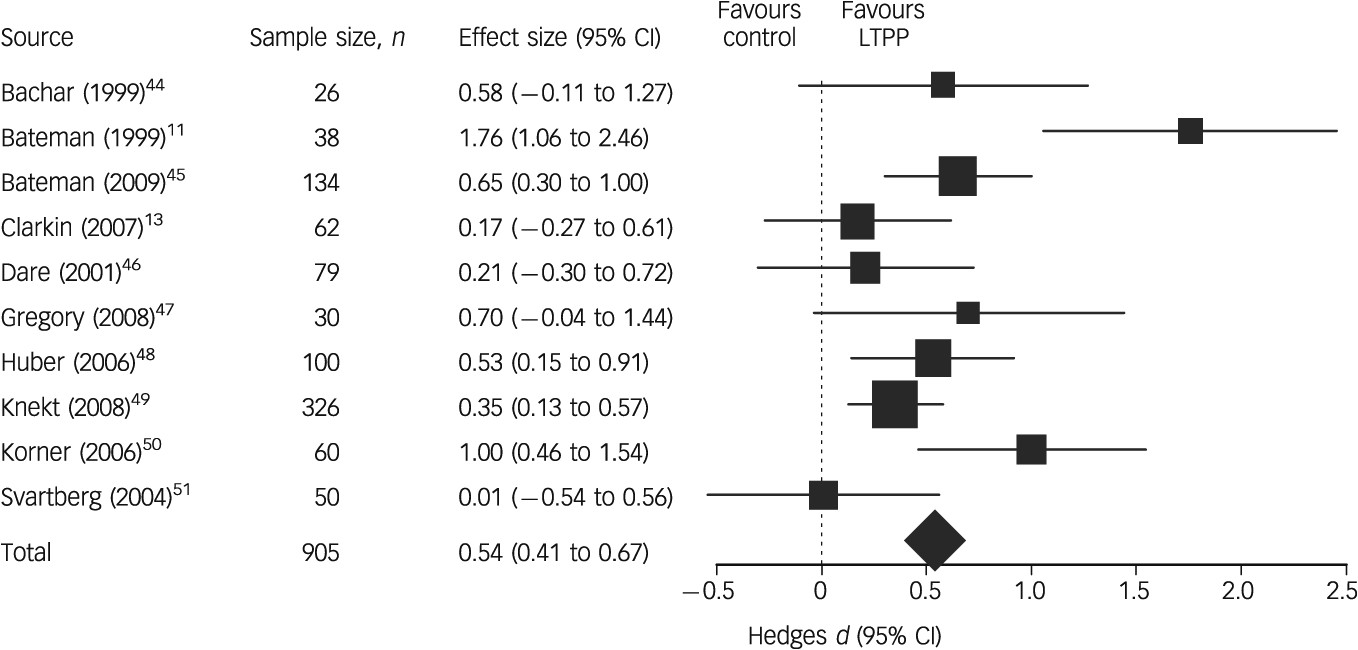

16,27 In a study of depressive disorders, for example, a reduction in depression could be attributed only to target problems, not to psychiatric symptoms. However, this procedure may artificially narrow the data basis for the estimation of actual therapeutic effects in the respective outcome areas. In order to avoid this problem in this meta-analysis, we first assigned each outcome measure to one (and only one) of the three domains of psychiatric symptoms, personality functioning or social functioning. Overall outcome was assessed by averaging the effect sizes of these three areas. To obtain information about changes in target problems, outcome measures referring to criteria specific to the patient group under study (e.g. measures of depression in depressive disorders), which were in the first step of evaluation assigned to one of the aforementioned three areas, were additionally assigned to the domain of target problems. This means that the results for target problems are not independent of the other three areas, but more realistic estimates of therapeutic effects will be achieved. As a measure of between-group effect size for continuous measures, we calculated Hedges’

d and the associated 95% confidence interval.

33 This measure is a variation of Cohen’s

d which corrects for bias due to small sample sizes.

33 Hedges’

d was calculated by subtracting the mean pre-treatment to post-treatment or follow-up difference of the control condition from the corresponding difference of LTPP, divided by the pooled pre-treatment standard deviation. This quotient was multiplied by a coefficient

J correcting for small sample size to obtain Hedges’

d. If a study included more than one LTPP or comparison group, we used the averaged effect sizes of these groups. We aggregated the effect sizes estimates (Hedges’

d) across studies, adopting a random effects model which is more appropriate if the aim is to make inferences beyond the observed sample of studies.

34 To obtain a mean effect sizes estimate we used MetaWin version 2.0 for Windows.

35 If the data necessary to calculate effect sizes were not published in the article, we asked its authors for this information. If necessary, signs were reversed so that a positive effect size always indicated improvement. In order to examine the stability of psychotherapeutic effects, we assessed effect sizes separately for assessments at the termination of therapy and follow-up. If data pertaining to completers and intention-to-treat (ITT) samples were reported, the latter were included. To control for bias related to withdrawal, we additionally carried out ITT analyses. For studies that did not report ITT data we conservatively set the effects for patients who withdrew after randomisation to zero. By this procedure, the effect sizes reported for the completers sample were adjusted for missing ITT data. If a study, for example, reported a pre-post treatment difference of 0.40 for a group of 20 patients who completed the study with 5 patients having withdrawn, we used an adjusted difference of 0.32 (0.40 × 20/25) for the ITT analysis. Tests for heterogeneity were carried out using the

Q statistic.

33 To assess the degree of heterogeneity, we calculated the

I2 index.

36 In cases of significant heterogeneity random effect models are more appropriate.

34,37 To control for publication bias, tests for asymmetry in funnel plots and ‘file drawer’ analyses were performed.

36–39 Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 15.0 and MetaWin version 2.0.

35,40 Two-tailed tests of significance were carried out for all analyses. The significance level was set to

P = 0.05 unless otherwise stated. If more is better, outcome should increase with dosage and duration of treatment. For this analysis we used within-group effect sizes which were calculated for each condition by subtracting the post-treatment mean from the pre-treatment mean and dividing the difference by the pooled pre-treatment standard deviation of the measure.

41,42 If more than one LTPP condition or more than one control condition was included, we treated them separately in this analysis. Spearman correlations were assessed between within-group effect sizes and both duration of treatment and number of sessions.