This exercise is designed to test your comprehension of material relevant to this issue of Focus as well as your ability to evaluate, diagnose, and manage clinical problems. Answer the questions below to the best of your ability with the information provided, making your decisions as if the individual were one of your patients.

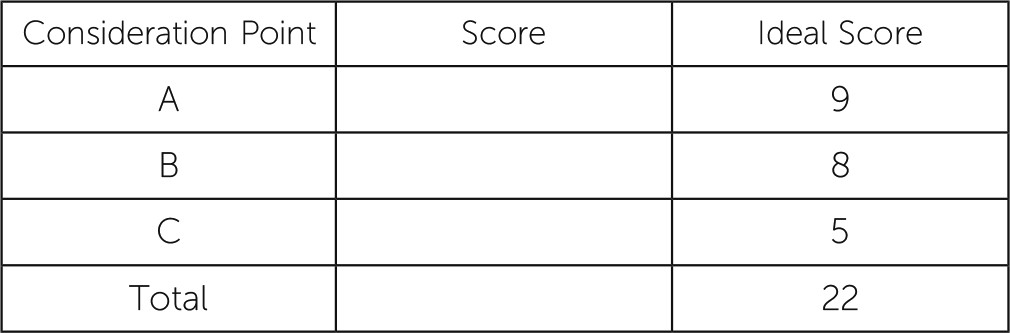

Questions are presented at “consideration points” that follow a section that gives information about the case. One or more choices may be correct for each question; make your choices on the basis of your clinical knowledge and the history provided. Read all of the options for each question before making any selections. You are given points on a graded scale for the best possible answer(s), and points are deducted for answers that would result in a poor outcome or delay your arriving at the right answer. Answers that have little or no impact receive zero points. At the end of the exercise, you will add up your points to obtain a total score.

Case Vignette

You are a psychiatrist in private practice. You receive a phone call from a woman who asks if you can see her son. She tells you he is 22 years old and has a job but suffers from horrible depressive episodes and panic attacks and has not slept in weeks. You explain that her son is old enough to make appointments himself and for legal reasons, should. She responds that she knows that and says he asked her to make an appointment for him. She also says she does a lot of things for him because he needs her help. She asks if she can tell you more about him and that, if you agree to see her son, she would ask him to call for the appointment after he returns from work. You ask who else is in the family, and she says her son has an older sister who lives in New York City and works for a large bank. She says her daughter could likely tell you more about her son if you are interested. The daughter is married to a man who is a youth minister and travels a lot. “We’re not religious,” the mother tells you. “My son used to hear voices that he was convinced were God and the Devil, but I have a suspicion it’s because he went to a Catholic school.” She tells you her mother and father divorced when she was a child because her father had schizophrenia and “he drove her crazy.”

You agree to see the patient.

Case Vignette Concludes

When the mother shows up with her son, she hands you a packet of cognitive testing results from when the patient was 7 years old, plus a typewritten family history that includes information about his sister; then his family is divided according to his mother and father and traced back to his grandparents, of whom only his maternal grandfather is still alive. Following this is a genetics report that details how the patient should respond to a variety of medications, also from when the patient was 7 years old.

You notice immediately from the family history that his sister, father, paternal grandfather, and maternal uncle were diagnosed as having conditions related to the present DSM-5 diagnosis of ASD. You read more carefully that different types of mental illness, including anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety), “odd/inappropriate behavior,” childhood-onset schizophrenia, childhood-onset bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcoholism, “depression,” and “serious anger problem” were diagnosed among all members of the family on both sides.

After glancing at the patient’s cognitive testing, you note that the patient received very high marks on the Differential Ability Scales (2nd ed.) as well as on the processing speed index from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4th ed.; WISC-IV) and that he was in the 91st percentile, or the superior range. You then note that in the area of nonverbal reasoning, he was in the 70th percentile, or the average range. You also note that according to the WISC-IV processing speed index, he was also in the average range.

According to his core language assessment, he was in the average range. Written in boldface print, you note that his “parents both endorsed clinically significant symptoms of hyperactivity and elevated symptoms of problems with attention.”

Answers: Scoring, Relative Weights, and Comments

Points awarded for correct and incorrect answers are scaled from best (+5) to unhelpful but not harmful (0) to dangerous (−5).

Consideration Point A.

ASDs can be diagnosed when children are younger than 3 years and when parents typically begin to wonder if there is something untoward happening concerning their child’s development. The mean age when parents become concerned is 19.1 months, and they typically seek professional advice by the time their children are 24.1 months of age. A common presentation, in perhaps one third of cases, suggests that parents witness what they consider to be a “set-back in development,” or a regression of verbal and nonverbal communication and social abilities between ages 36 and 54 months.

Often parents will notice that their children seem uninterested in voices, do not make direct eye contact, do not put their arms up to be lifted, or do not display any version of an anticipatory gesture. Autistic infants frequently scream and cry as a means of showing their needs. They also may pull an adult toward whatever it is they want, all the while not revealing any congruent facial expressions. When they display an understanding of an adult or other children, their gestures tend to be stereotyped repetitive actions. Although they may be attracted to adults, they seem unable to differentiate between adults, as if the adults, including parents, were interchangeable. They may respond to small physical gestures, such as a tickle, but generally do not follow their parents around the house or attempt to imitate their activities. As the children age, they may demonstrate affection for close family members but typically do not initiate these social contracts. Adults may feel these children lack a sense of humor, and these children may get into trouble for engaging in socially inappropriate behaviors. Parents may suspect that their child is deaf.

Consideration Point B.

Diagnosing ASD can be a complicated process. It is fairly common for practitioners to label a child’s difficult behavior as “on the spectrum” and prescribe antipsychotics, hoping that the dopaminergic blockade will change the child’s behavior. In this case it is clear that the mother is drawing from many years of coping, pointing to evidence of genetic heritability from numerous members of her son’s family—ASD more from the paternal side, different mental illnesses from the maternal side—and cognitive testing of her son when he was much younger. From what she has said and presented to you, it seems that she has invested a lot of time and money in various medication therapies as well as genetic testing of his enzymes.

Whether or not a person had paradoxical reactions to medications is not pathognomonic of ASD. Difficult behavior, likewise, is not pathognomonic of ASD but could be a manifestation of other mental illnesses, including anxiety disorders, other affective disorders, or disruptive behavioral disorders. ASD is considered a clinical diagnosis, described in DSM-5 as impairments in social communication and interaction and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior. As was noted earlier, parents or caregivers may misconstrue many of these “impairments” as aloofness, a “different” sense of humor, even deafness. Also, there may be comorbid psychiatric or medical disorders inherent or complicating the presentation. Many medical illnesses can masquerade as ASD, including tuberous sclerosis, Mobius syndrome, Down syndrome (or general mental retardation), congenital deafness, or blindness.

Because ASD can be so complicated, many centers have prerequisites for making such a diagnosis for a person to benefit from whatever therapies the center offers, including the use of various diagnostic rating scales. Consequently, diagnosing ASD may require various metrics used for general cognitive testing or helping to diagnose suspected ASD.

Consideration Point C.

It is important to remember that ASDs are considered chronic. Some aspects of ASD that are related to social, conceptual, linguistic, or obsessional difficulties may “improve” as a person ages. Often these issues persist, although in a different form. Some studies relate specifically to a person’s adaptive behaviors and have used the VABS and found no appreciable relation to a person’s IQ, except to suggest that higher initial IQs helped a person improve on intellectual and language abilities.

C.3

(0) Functioning independently is helpful but does not indicate that a person with ASD will never require therapeutic interventions again.

C.5

(−5) There is absolutely no evidence of an infectious process that “causes” ASD; therefore, using antibiotics or IVIG has its own inherent problems.