INTRODUCTION

Suicide is currently the second leading cause of death worldwide among youth aged 12–24 years.

1 The majority of youth who die by suicide meet criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder; of these, bipolar disorder confers greatest risk. Nearly one-third of youth with bipolar disorder attempt suicide at least once by mid-adolescence,

2 60% attempt at least once in their lifetimes, and up to 20% will die by suicide, rendering the risk of death by suicide 60 times higher among individuals with bipolar disorder than that of the general population.

3Data from cross-sectional, prospective, and meta-analytic studies identify specific factors associated with elevated risk for suicidal behavior among individuals with bipolar disorder, one of the most potent of which is early age of bipolar illness onset.

4 Others include mixed episodes, psychosis, non-suicidal self-injury, family history of suicide, and history of abuse.

5–7 Identification of these group-level risk factors is critical, but yield information about risk for the group as a whole. As such, they may not reliably predict risk for any specific individual. Moreover, since these risk factors are both numerous and heterogenous, it is not surprising that a recent large-scale meta-analysis shows that these factors predict risk for suicide attempt only slightly better than chance,

8 as do clinical judgment,

9 and clinical rating scales.

10Given that suicidal behavior results from a complex interaction of factors, suicide prevention efforts among high-risk groups like individuals with early-onset bipolar disorder could be enhanced by the capacity to predict an

individual's risk for SA over a specified time period. A risk calculator (RC) is a clinical tool that uses an optimally identified set of risk factors to compute the probability of a specified event in an individual patient.

11 RCs are widely used by physicians to enhance clinical decision making across several health conditions including stroke and cancer.

12,13 Recently, RCs have been developed to predict course and treatment response in psychiatric disorders including psychosis

11 and depression.

14 Our group developed RCs to predict 5-year bipolar disorder onset among offspring of parents with bipolar disorder,

15 risk for progression from bipolar, not otherwise specified (NOS), to bipolar-I/-II among youth,

16 and risk for mood recurrence among young adults with bipolar disorder.

17Efforts to create RCs to predict individual-level risk for suicide attempt have been limited to date. Spittal et al.

18 developed the 4-item Repeated Episodes of Self-Harm (RESH) scale to predict 6-month risk of self-harm repetition (with or without suicidal intent) among hospitalized individuals, with AUC = 0.75. Fazel et al.

19 describe the 17-item OxMIS (Oxford Mental Illness and Suicide Tool) to predict suicide death over 1 year among individuals with severe mental illness (AUC = 0.71). These RCs demonstrate moderate predictive power (62%–100% at varying thresholds and 75%, respectively), but low sensitivity (6%–74% and 55%) among varied samples. Prediction may be improved by constructing tailored models within particular groups at higher risk, like individuals with early-onset bipolar disorder. Furthermore, ultimate clinical benefit of RCs is contingent upon inclusion of predictors readily assessed across settings. To highlight, Melhem et al.

20 computed a risk score for suicide attempt over 12 years among offspring of parents with mood disorders using six readily assessed clinical factors. The model yielded high sensitivity (87%) and moderate improvement in specificity over the aforementioned tools (63%), but lacks their temporal specificity.

We describe development of a RC to predict an individual's one-year risk for SA for youth with bipolar disorder followed for a median of 13.1 years in the multi-site longitudinal Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study. To enhance clinical utility, predictors of suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder readily assessed in clinical practice were identified from systematic reviews.

RESULTS

Rates of Suicide Attempt Over Follow-Up

Over a median of 13.1 years of follow-up, we observed 249 suicide attempts among 106 individuals. Twenty-seven percent of the sample (106/394) had at least one suicide attempt over follow-up, and 14% (54/394) had ≥2 suicide attempts. The estimated median time to first attempt over follow-up was 4 years (range = 0.5–12 years). Among participants with a suicide attempt over follow-up, median rate was approximately one attempt per 7 years.

One-Year Risk Calculator

The participant randomization procedure yielded a training sample with 200 participants with 2751 observations, and a testing sample with 194 participants with 2776 observations. Except for a slightly higher rate of disruptive behavior disorder in the testing sample (63% vs. 51%, p = 0.01), there were no significant between-subsample differences in length of follow-up, number of assessments, duration between assessments, number of suicide attempts, demographic or clinical factors. Overall, the participant randomization procedure yielded highly balanced subsamples.

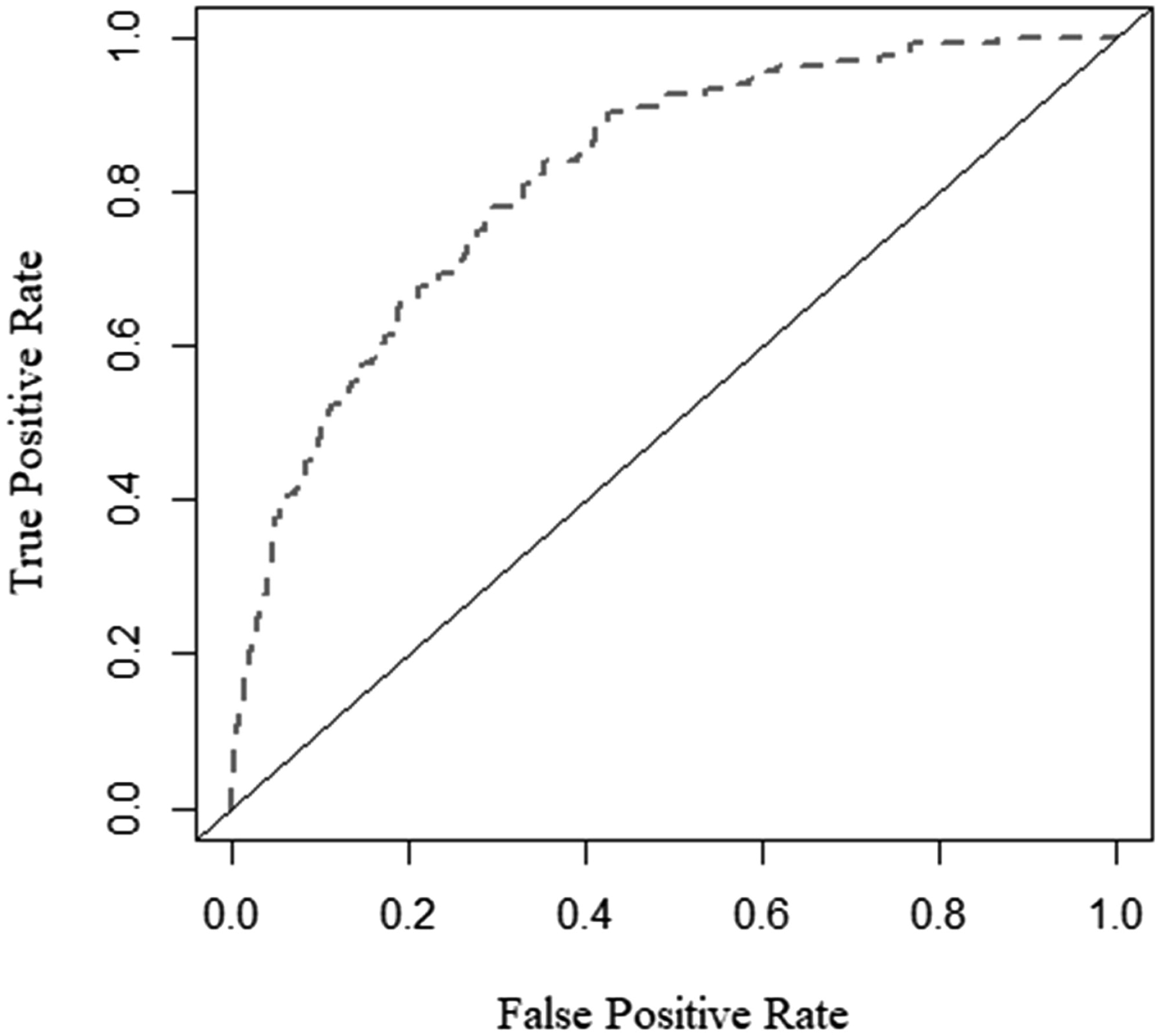

The test AUC of the full model's one-year risk predictions was 0.82 (0.79, 0.85;

Figure 1). Predicted and observed suicide attempt risk were consistent through the range of risk scores and did not significantly differ (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ

2 = 10.24, df = 8,

p = 0.25), indicating no evidence of miscalibration. Furthermore, average predicted one-year risk in the testing sample (mean = 0.050, median = 0.029) was similar to the observed suicide attempt rate in the testing sample (0.049).

Table 3 shows test prediction metrics across a range of predicted risk thresholds; sensitivity and specificity are maximized at 0.73, with a predicted risk threshold of 0.036 (i.e., if predicted risk ≥0.036, predict SA; if predicted risk <0.036, predict no suicide attempt).

Of the 21 predictors in the model (

Table 4), 10 accounted for >90% of the cross-validated relative influence in the model (direction associated with increased risk noted in parentheses): (1) age of mood disorder onset (younger); (2) non-suicidal self-injury history (presence); (3) current age (older); (4) history of psychosis (present); (5) SES (lower); (6) most severe past 6 months depressive symptoms (i.e., PSR 1–6; higher); (7) history of suicide attempt (present); (8) family history of suicide attempt (present); (9) SUD history (present); and (10) lifetime history of physical/sexual abuse (present). Of note, when parametrically estimating the predictive influence of each level of a trichotomous variable, presence in the past 6 months reliably predicted higher suicide attempt risk than lifetime history.

When reformulating the model to predict medical lethality of suicide attempts, nine out of the ten most influential predictors in the RC outlined above remained among the top ten most influential predictors of medical lethality (Table S1). The notable exception was non-suicidal self-injury history, which, while highly predictive of risk for suicide attempt, was not highly predictive of medical lethality. This predictor was replaced by family history of bipolar disorder as one of the ten predictors comprising more than 90% of the cross-validated relative influence in the medical lethality model.

Sensitivity analyses indicated no significant AUC decrements after individually eliminating any predictors in the model, with the largest decrement = −0.03 (−0.04, 0.03) when removing age of mood disorder onset. Sensitivity analyses excluding youth with bipolar-II and –NOS (i.e., limited to bipolar-I only) yielded a minimal increase in AUC (0.83), with the same 10 predictors accounting for the top 90% of relative influence in the model. Similarly, sensitivity analyses excluding observations with concurrent lithium use, and separately including only those with concurrent lithium use, showed no significant change in AUC. Substituting dichotomous (i.e., presence in the past 6 months; lifetime history) for trichotomous risk factors in the model yielded nearly identical AUCs and influential variables, indicating minimal impact on model performance. Lastly, dividing substance use disorder history into two separate predictor variables for alcohol use disorder and other substance (i.e., drugs) use disorder yielded a nearly identical AUC. Drug use disorder was a slightly more influential predictor than alcohol use disorder (4.54% relative influence vs. 1.89%). However, it is important to note that drug use disorder over follow-up was slightly more prevalent than alcohol use disorder in this sample (31% of participants vs. 26%), and within participants with substance use disorder, drug use disorder was much more persistent over follow-up than alcohol use disorder (27% of follow-up weeks on average vs. 16%).

The ridge regression trained and tested for comparison to the boosted model performed comparably weaker, with a test AUC = 0.71 and maximized sensitivity and specificity at 0.65 with predicted risk threshold = 0.0375. Predicted and observed suicide attempt risk were consistent through the range of risk scores and did not significantly differ (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 = 6.58, df = 8, p = 0.58), indicating no evidence of miscalibration.

A reduced model was trained using only the ten predictors accounting for the top 90% of cross-validated relative influence. Results indicated that model discrimination remained approximately unchanged in the reduced model at 0.82 (0.79, 0.84), and optimal sensitivity and specificity improved to 0.74.

DISCUSSION

We describe the first individual-level 1-year RC for suicide attempt among the high-risk group of individuals with early-onset bipolar disorder. This RC offers promise for clinical use due to its reliance on just ten readily assessed demographic and clinical variables, including current age, age of mood disorder onset, SES, family history of suicide attempt, personal history of suicide attempt, non-suicidal self-injury and psychotic symptoms, and recent (past 6 months) threshold depressive symptoms. Additionally, sensitivity and specificity (AUC = 0.82) of the RC meets or exceeds that of most RCs utilized in clinical practice for other medical (e.g., cardiovascular disease, AUC = 0.76–0.79) and psychiatric conditions (e.g., new-onset psychosis, AUC = 0.71).

11Alternative approaches to prediction of suicidal behavior in high-risk groups include screening tools (e.g., the Comprehensive Suicide Risk Assessment for veterans

34) and self-reports (e.g., the Concise Health Risk Tracking Self-Report for adults with BP

35), but these have lower sensitivity and specificity for predicting near-term suicide attempt, and rely on patient-reported symptoms which may be subject to bias. Recent studies have attempted to enhance reliability and scalability of suicide risk prediction tools by applying machine learning algorithms to electronic medical record data, for example,

36 yielding models with similar predictive power as this RC. While these models have the benefit of automated, large-scale risk detection in healthcare systems, they are limited to individuals for whom prior medical records are available. Thus, models dependent on electronic medical record data from within a single healthcare system may not be reliable or even implementable among individuals with mental health disorders, who are more likely to be uninsured and seek treatment from safety net providers.

37 Indeed, when de la Garza and colleagues

38 applied machine learning to predict suicide attempt in a representative sample of adults in the Unites States, socioeconomic disadvantage, lower education level and past year financial crisis were among the ten most potent predictors, highlighting inherent behavioral healthcare disparities.

A clinical tool like the RC which we describe relies on demographic and clinical information commonly gathered during standard psychiatric assessment, and as such, may hold promise to enhance clinical care. For example, results could trigger notifications alerting providers of individuals at elevated risk and changes in risk status. Elevated risk scores could further indicate the need for more detailed imminent suicide risk assessment using evidence-based tools, as well as creation, update, and/or review of the individual's safety plan.

39 Subsequent intervention may include consideration of appropriate frequency, type and level of care for the individual's predicted risk. Additionally, outreach efforts may be initiated for high-risk patients who do not attend scheduled visits, as implemented in the Veterans Affairs health system.

40 This approach is closely aligned with the aims of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention's “Project 2025,

41” a nationwide initiative to reduce the annual suicide rate 20% by 2025. This plan specifically highlights enhanced identification of at-risk individuals via evidence-based practices within systems of primary and behavioral health care as one of four priority areas with greatest potential for impact.

While the RC we describe yields highly accurate individual-level prediction, a RC score does not replace clinical judgment. Indeed, additional factors shown to predict elevated risk for suicidal behavior among youth with bipolar disorder—including several included herein—did not emerge as highly influential in the RC (e.g., sex at birth, mixed symptoms

25), it is possible that such factors exert their effects through the more highly predictive factors in the RC. These and other established risk factors (e.g., comorbid personality disorder

5) should also be considered for select individuals with early-onset bipolar disorder. In some cases, the RC may under- or overestimate risk, and additionally does not yield detailed information on specific aspects of suicide risk (e.g., intent, lethality), rendering further clinical and suicide risk assessment critical. Of note, our analyses examining a secondary RC to predict suicide attempt lethality demonstrates remarkable predictor overlap with the RC to predict suicide attempt, with nine of the top ten most influential variables remaining the same. The exception is history of non-suicidal self-injury, which is highly predictive of risk for suicide attempt, but not of medical lethality. Together, these findings indicate the RC holds promise as a data-driven tool to augment and guide suicide risk assessment and treatment planning.

Regarding research implications, the RC may help identify individuals during elevated periods of risk for whom novel suicide prevention approaches may be examined. Additionally, future studies may further enhance person-level prediction of near-term suicide risk by combining the RC with cognitive tasks and/or biological indices (e.g., neuroimaging, polygenic risk scores) implicated in suicide risk.

10Strengths of this study include the well-characterized sample of individuals with early-onset bipolar disorder followed longitudinally with validated measures. However, included risk factors were limited to those collected and, therefore, are not exhaustive (e.g., emotional abuse). Additional limitations include a primarily White sample, rendering examination among more diverse samples a critical future direction. COBY participants were recruited from clinical settings, possibly limiting generalizability of the results. Next steps include external validation in an independent sample of individuals with early-onset bipolar disorder, and examination among community samples and individuals with adult-onset bipolar disorder. Future work may also aim to identify models that reliably predict risk over even more proximal timeframes (e.g., 1 month).

Using just ten demographic and clinical factors commonly assessed in clinical practice, this individual-level RC for early-onset bipolar disorder reliably predicts one-year suicide attempt risk. This low-burden tool, if validated, offers promise to enhance suicide risk assessment and management in this high-risk population.