Deficits in both cognition and olfaction are associated with schizophrenia.

1,2 A large body of research in olfaction has shown unequivocally that schizophrenia patients have impaired ability to identify smells (reviewed by Atanasova

3). We and others have shown this impairment to be correlated with deficits in motivated behavior and emotional expression

4–8 as well as with impaired verbal and nonverbal memory.

6,9–11 It is not clear, however, whether these impairments reflect a general deficit in cognition or whether they relate to specific pathways of olfactory processing. This question might be illuminated though comparisons of results in different sexes, given that brain structures, chemistry, and function are sexually dimorphic;

12,13 however, few researchers have explicitly examined whether sex modifies how odor identification relates to cognitive functioning.

Other aspects of olfaction studied in schizophrenia include acuity (or sensitivity or threshold), discrimination, familiarity/recognition, intensity and pleasantness; however, the findings have been variable (reviewed by Atanasova

3). For example, patients with schizophrenia have shown decreased,

14–17 increased

17,18 or unchanged mean values for odor acuity,

2,10,19–23 leading some to suggest that odor acuity is not altered in schizophrenia.

3 One interpretation of this could be that the deficits in smell identification in schizophrenia reflect abnormalities in central processing, whereas the supposedly unchanged acuity reflects normal peripheral processing.

3 This view would be supported if acuity were found to be unrelated to cognition and if results were true for both sexes. Little is known, however, about how olfactory acuity relates to cognition and to sex in those with schizophrenia. Furthermore, given sex differences in structure, connectivity and function in regions of the brain involved in olfaction in humans,

24 surprisingly little is known about how sex modifies olfactory processing in humans, either in normal people or schizophrenia patients. Research examining olfaction and cognitive processes in schizophrenia rarely includes sex stratification. One study that did address sex differences did not assess odor acuity.

25 Another study suggested that there was no relationship between acuity and cognition in schizophrenia,

10 but did not separate the sexes.

The vast majority of schizophrenia research has not stratified the results according to sex. Instead, female findings have been generally added to those of the males. Although there may be obvious reasons for analyzing both sexes together (e.g. small sample size), it is also surprising given the burgeoning literature on sex influences on the brain,

13 and the growing recognition that olfactory probes hold great promise as biomarkers for understanding schizophrenia.

26 In the current study we examine how measures of cognition, with particular focus on memory and attention, relate both to smell identification and olfactory acuity in men and women with schizophrenia. While the emphasis is on sex differences in schizophrenia patients, we also included a smaller sample of healthy control subjects.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that odor detection and smell identification are both associated with cognitive performance in patients with schizophrenia. However, this association is dissimilar and significantly modified by sex.

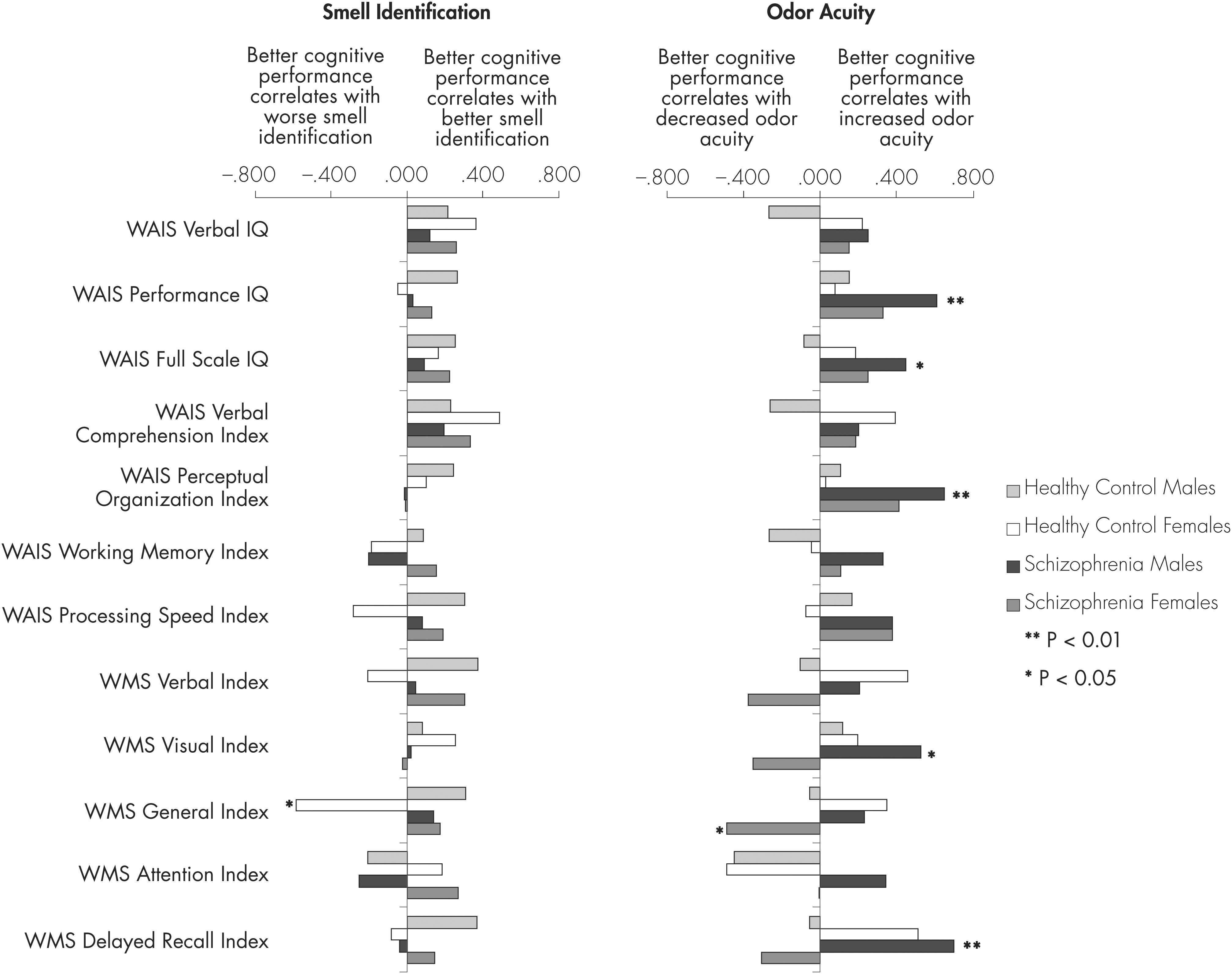

Female and male patients’ correlations between olfactory tasks and cognition significantly differed in the strength of the association for some measures, but were associated by sex for other measures. The most notable contradiction between the sexes occurred for the association of odor threshold with memory (WMS-R), showing opposing correlations in male and female patients (

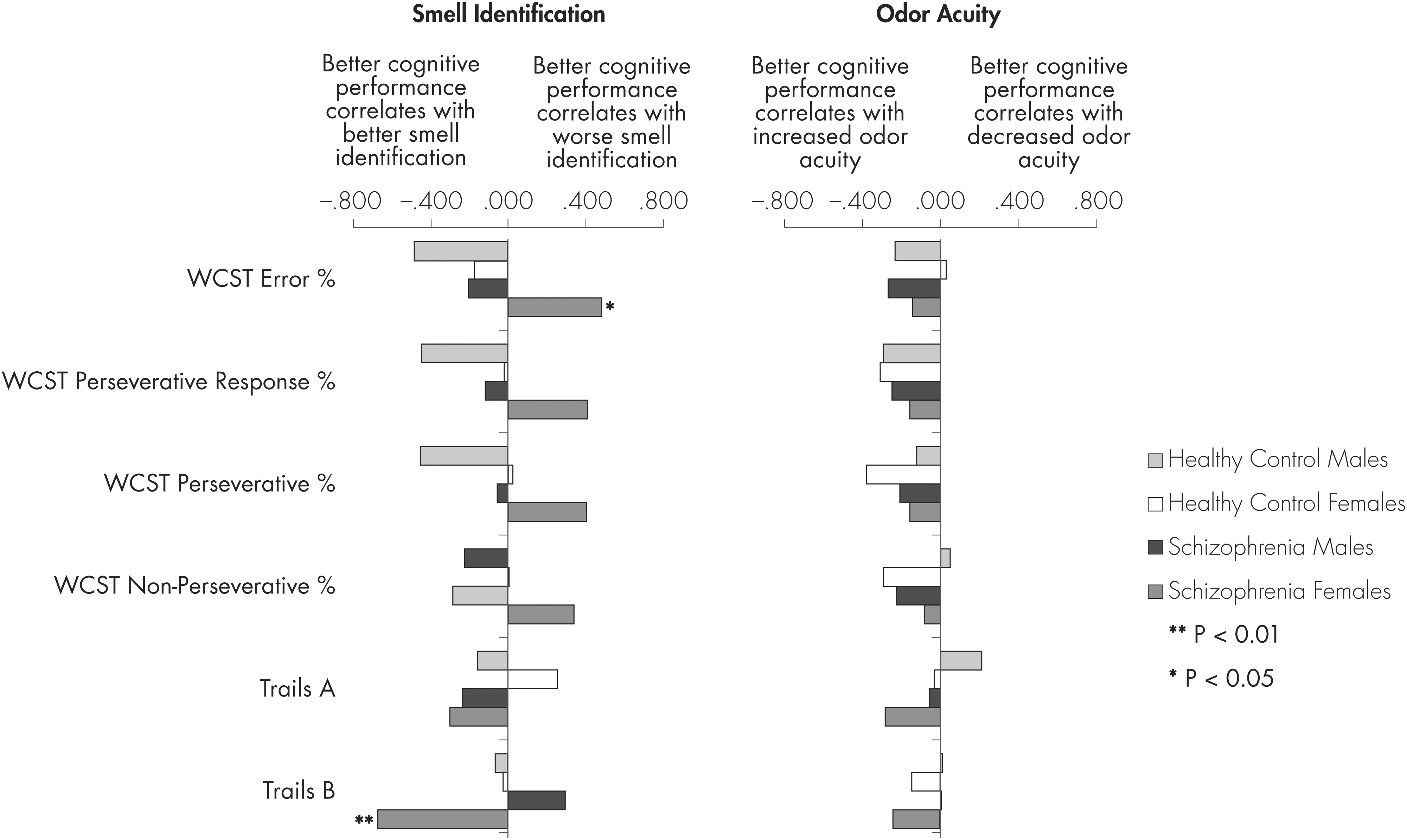

Figure 1). Another contradiction was found in smell identification and attention; male patients’ scores were positively associated with better performance on an executive functioning task (WCST) and faster processing speed (Trail Making Test B), whereas better smell identification scores in females were related to more errors on the executive functioning task (

Figure 2). The female patients’ results seem to be counter-intuitive in that better cognitive performance correlated with lesser performance on the olfactory tasks. This may be due to females de-emphasizing olfactory processing in proportion to certain cognitive abilities, such as attention.

Sex differences were also observed in olfactory performance and other cognitive tasks. For smell identification, female patients had stronger correlations to intelligence scales (WAIS-III) than male patients, whereas for odor threshold the associations were weaker in the females than the males (

Figure 1). Given that the sex differences, tested as statistical interactions, were highly significant (

Table 3), these findings may imply fundamental differences in the mechanisms of olfactory processing between male and females. A differential modulation of olfactory processing in light of higher cognitive processing may have evolved in women to optimize sex-specific outcomes of mating, reproduction, and childrearing.

Our results comparing the means and distributions of the two olfactory measures in male and female patients and the results of comparisons between patient and control groups are compatible with previous studies (

Table 1). We found that females performed better on smell identification and had somewhat greater acuity than males; schizophrenia patients of both sexes had lower smell identification scores than their sex-matched controls. For odor acuity, we found that the female patients’ scores were higher than those of the controls, but they also demonstrated a larger variance.

Studies on odor acuity in schizophrenia have revealed contrasting results. Some reports that acuity is elevated, whereas others indicate that acuity is decreased or similar to that of controls, leading to a consensus that it is unaltered in schizophrenia.

3 Our finding of increased variability in odor acuity sheds light on this controversy. Enhanced odor acuity detection may reflect the reduced gating of sensory stimuli that is well described in the disease (see Martin et al

35). The large variability in the measure is consistent with the presumed heterogeneity of schizophrenia.

36The negative association between odor threshold and attention in the controls (WMS-R attention index in

Figure 1) was surprising as it suggests that decreased attention in healthy people might be related to hyper-acuity for odor detection. However, a compatible finding was reported in people with attention deficit disorder.

37 Attention was not related to odor acuity in our schizophrenia patients, perhaps because of defective attention in the disease. Defective attention and failed inhibitory processes are closely associated with the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.

38 Although historical precedents have traditionally considered odor identification and odor acuity to reflect central and peripheral processes respectively,

39 the latter measure of olfaction also depends on the synapses of olfactory receptor neuron axons in the olfactory bulb, which is under the control of higher centers.

40Moreover, the fact that patients with schizophrenia show sex differences in the relation of olfaction to memory, attention, and other cognitive abilities corroborate results from other studies that have found sex differences in the relative size of brain structures involved in olfaction, and in their connectivity and function. A number of the same structures are abnormal in schizophrenia, on the one hand, and are functionally important in cognitive functioning, on the other hand. For example, females have greater gray matter in the orbital prefrontal cortex,

41 a high level multimodal olfactory system that can inhibit subcortical regions; whereas males have greater gray matter in the entorhinal cortex that receives direct input from the olfactory bulb.

24 Research shows that sex differences help explain why larger regional olfactory brain volumes variably predict enhanced or reduced olfactory function.

42 One study found that stimulation from background odors impaired the reaction time performance of healthy males, but not females.

43 Other variability may be related to the etiological heterogeneity of schizophrenia. Smell identification has been associated with both the orbitofrontal and the dorsolateral prefrontal circuitry in patients with schizophrenia.

4,8,44 These regions play greater roles in metacognitive executive function versus emotional/motivational function, respectively.

45 Dysfunction in either brain circuit is reported in individual patients with schizophrenia.

46A particular strength of our study is that the patients and the controls were as well matched cognitively as may be possible. They differed in working memory, processing speed, verbal intelligence and general memory; deficits which are part and parcel of neurocognitive impairment profiles in schizophrenia.

47,48 It is noteworthy that olfaction was significantly associated with these subtle cognitive deficits, even though the mean threshold and smell identification scores did not significantly distinguish between cases and controls in this sample.

There are several limitations with this study that bear some discussion. We used only phenyl ethyl alcohol (PEA) to test acuity. Although the thresholds for detecting different odorants are highly correlated in humans,

49 other odorants should be examined in future studies. It should also be noted that our cases were all on stable medications and in an optimized clinical state. Although there is no evidence linking medication status to performance on smell identification,

50 a medication effect has been reported for causing asymmetrical olfactory thresholds in schizophrenia.

51 With regard to verbal cognitive performance, we and other groups have reported significant links between smell identification and verbal ability.

11,25,52 These associations were positive in all of our groups, although the relationships did not reach significance. Also, studies in nonschizophrenia populations have shown that reduced olfactory functioning in healthy subjects is related to poor cognitive processing speed, attention and working memory, vocabulary level, reasoning ability, confrontation naming, verbal memory, and general cognitive impairment (e.g. Dulay et al

53). Our sample size of healthy subjects was too small to uncover any of these relationships in our data. Despite less education in the schizophrenia patients, their similar intelligence scores suggest that less education in the schizophrenia patients may be an artifact of the illness, likely due to avolition or other symptoms. Therefore, we did not adjust the analyses for education; although doing so produced similar results (data not shown). We also did not separately analyze threshold data from right and left nostrils, since we were examining cognitive associations and information from both nostrils converge at the anterior olfactory nucleus.

54 Event-related potential studies of central olfactory processing also do not reveal main effects for right versus left nostril odor presentations.

55,56 We did not control for menstrual cycle, which could theoretically modulate differential relationships of odor threshold and smell identification to cognitive functioning between males and females. Lastly, we included both patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder in the study. As both disorders are heterogeneous, future studies should examine olfaction, cognitive functioning, and sex differences in more homogeneous schizophrenia groups.

In summary, olfactory processing is implicated in social, sexual and other goal-directed human behaviors, including cognitively demanding tasks. This link between olfaction and cognitive functioning, such as memory and attention, is sexually dimorphic. Sexually dimorphic features are present in individuals with schizophrenia as well. The failure of research studies to account for these dimorphic features may underlie some of the roadblocks that have been encountered in etiological research and treatment studies (e.g. treatment of negative symptoms). Our present study highlights that olfactory processing is an appealing model in which to study the links between perception and cognitive functioning in schizophrenia, a disorder that includes deficits in both olfactory processing and cognitive abilities. By combining male and female groups to study olfaction, real and important differences between the patient and control groups may be masked. Our findings make it clear that research aiming to discover differences between schizophrenia patients and controls should separately consider the sexes. Combining them is likely to obscure the observation of abnormalities that are sexually dimorphic. Sex stratification may similarly enhance the utility of olfactory research in other neuropsychiatric disorders as well.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health R01MH066428 and 5K24MH001699-10 to DM, and AK was supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award. The funding sources had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in writing the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Drs. Malaspina and R. Goetz, and Mrs. D. Goetz were involved in the design and writing of the study protocol. Drs. Malaspina, Harlap, R. Goetz, Keller and Antonius, and Mrs. Messinger managed literature reviews and/or statistical analyses pertaining to the study. Drs. Malaspina, Harlap, Keller, R. Goetz, Antonius, Harlap, and Harkavy-Friedman, and Mrs. Messinger and D. Goetz were involved in the writing of various drafts and the final manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments: None to report.