Psychiatric disorders encompass a wide variety of nosological presentations traditionally classified as disorders of thought, affect, or impulse control. The pathophysiology of the vast majority of psychiatric disorders is complex and not well understood. There is a trend in psychiatry to explain mental illness with common denominators across diagnostic boundaries. One common element in severe mental illness is pervasive bad decision making (i.e., not taking medications, paying heed to command hallucinations, or attempting suicide). Despite the ubiquity of decision making in daily life, it has been largely neglected in the diagnosis and management of mental illness. Individuals’ choices are intimately related to disease outcome (hospitalization, incarceration, or suicide), which have been largely unchanged despite decades of research in neuroscience, psychology, and psychiatry.

Depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is characterized by two primary affective symptoms: sustained negative affect and reduced positive affect.

49 In general, decisions during depressed states are tainted by negative affect and distorted negative cognitions,

50 although some research suggests that mild levels of depression may be associated with more realistic self-assessments even in psychotic patients.

51 A number of studies have used monetary and nonmonetary paradigms to evaluate the reward system in depression. A consistent pattern of reduced activation of the ventral striatum, dorsal striatum, and VMPFC

52–54 in response to positive reward stimuli has been reported, but see also for discrepant results.

55 A real life consequence of altered reward processing in depression was demonstrated in a report of economic social interaction using the ultimatum game in which participants were asked to accept or reject a wide range of offers. Depressed patients exhibited a more negative emotional reaction to unfair offers, despite accepting more of these offers than controls.

56 Thus, depression appears to have a dual effect on the processing of reward and value: induction of excessive emotional responses and reduced willingness to reject unfair offers.

There is considerable evidence that monoamine systems, including doparnine (DA) and serotonin, are altered in depression.

57 Considerable monoamine loss is observed in high-risk states for depression.

58 In particular, DA neurotransmission in major depressive disorder (MDD) seems to be diminished, either by decreased DA release or intracellular signaling processing. These DA-related disturbances improve by treatment with antidepressants, presumably by acting on serotonergic or noradrenergic circuits, which then affect DA function.

57 Furthermore, DA receptor binding and amphetamine response in depression are correlated with altered brain activation in the ventrolateral PFC, OFC, caudate, and putamen.

59 Overall, depression seems to be associated with an alteration of the prefrontal control over the striatum leading to a dysfunctional frontostriatal connectivity. The impact of the frontostriatal system dysfunction in depression can be further understood considering the role of two circuits: the medial prefrontal cortex-ventral striatum, which underlies motivation, and the OFC-ventromedial caudate, considered to intervene in affective processing.

60,61In addition of serotonin’s role in impulsive aggression,

62–64 abnormal serotonin function has been linked to psychopathologies associated with negative affects such as depression and anxiety.

65–68 In contrast to impulsivity, depression is characterized by reduced behavioral vigor and enhanced aversive processing, with increased sensitivity to negative stimuli.

69 However, both impulsivity and depression have been associated with low serotonergic tone, based primarily on the therapeutic efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and observations that central serotonin depletion through dietary manipulation can induce depressive relapse.

70,71 Indeed, patients with depression show reduced tryptophan levels,

72 abnormal serotonin receptor function,

73 abnormal serotonin transporter function,

74 and elevated brain serotonin turnover.

75 However, the relationship between depression and serotonin is less clear-cut than that between impulsivity and serotonin. It is possible that the link between depression and serotonin might be indirect and mediated by associative learning

76 and/or disinhibition of negative thoughts.

77 Overall, a number of psychiatric disorders seem to disrupt the delicate balance between serotonin and dopamine, reflecting alterations in reward, risk assessment, and social interaction. This view is supported by the wide pharmacological profiles of the major psychotropics, such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, and even drugs of abuse.

Anhedonia, which is the loss of pleasure or interest in previously rewarding stimuli, is a key pathological element of MDD and predicts antidepressant response.

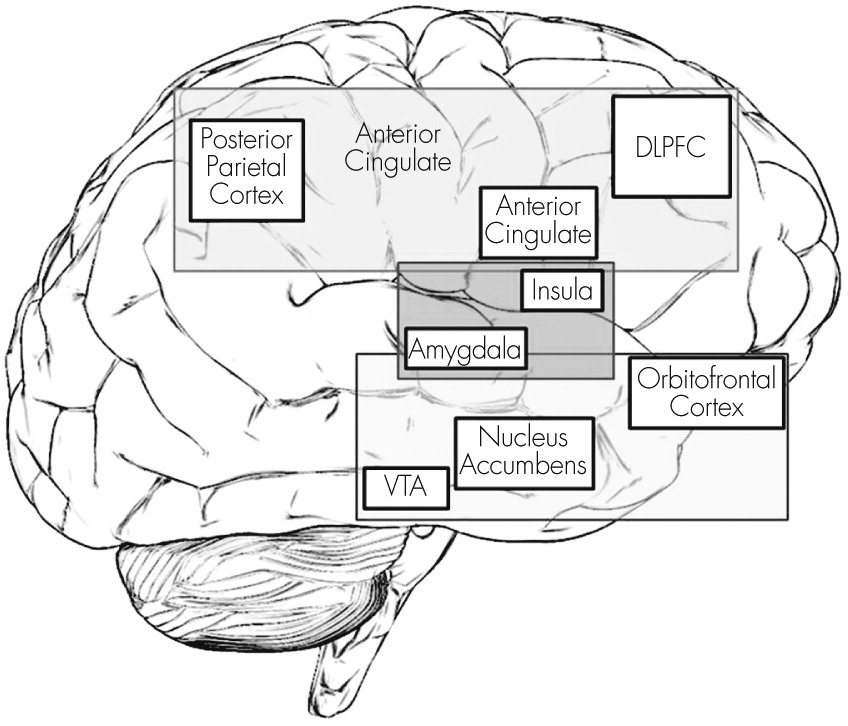

78 Anhedonia is associated with disruption of the frontostriatal valuation system and reward processing (

Figure 2). Anhedonic depressed patients exhibit reduced caudate

52 and OFC volume.

79 Decreased activation of the ventral striatum during reward selection, anticipation, and feedback are found in monetary tasks in nonmedicated anhedonic depressed patients.

80 Exploration of anhedonia in healthy volunteers showed decreased striatal activation and overactivation of the VMPFC during reward processing.

81There is debate as to whether anhedonia in depressed patients represents the inability to experience pleasure and engage in rewarding activities, or the inability to sustain positive affect. Neuroimaging data support both hypotheses. Epstein et al.

80 reported that unmedicated depressed patients exhibited decreased ventral striatum and DMPFC activation with positive stimuli. Additionally, the magnitude of ventral striatum deactivation correlated with decreased interest and pleasure during daily activities. In contrast, Heller et al.,

39 using an emotion regulation task found that depressed individuals were able to up-regulate positive affect, but failed to sustain NAcc activity over time. This diminished capacity to maintain positive affect was associated with decreased connectivity between the NAcc and mPFC. This concatenation of results points to an altered valuation system (frontostriatal circuit) in anhedonia, likely at the PFC level. This would be consistent with the therapeutic effects of psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which aims to identify and change dysfunctional patterns of thought and behavior. Furthermore, different forms of psychotherapy (e.g., interpersonal, behavioral activation, and cognitive behavioral therapy), for depression have shown normalization of PFC and striatum activity during reward tasks.

81,82Development

Depressed adolescents exhibit similar alterations of the reward system as their adult counterparts. Children between 9 and 17 years old with MDD had reduced neural response than controls in the caudate, OFC, ACC, and amygdala, as well as higher neuroactivation in the DLPFC and frontal pole during decision and outcome phases in a monetary reward task.

83 In addition, diminished caudate activation was correlated with lower subjective positive affect during follow-up.

83 The same group also reported that pretreatment striatal and medial PFC reactivity during a monetary reward task were predictive of response to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or pharmacological treatment. Relative to control subjects, adult individuals exposed to childhood adversity reported elevated symptoms of anhedonia and depression, rated the reward cues less positively, and displayed a weaker response to reward cues in the left globus pallidus.

84 Additionally, the combination of adverse early life experience and the short polymorphism of the serotonin transporter gene enhances negativity bias (perceiving more danger and risk than reward) and physiological reactivity to negative experiences.

49On the other hand, depression in older adults presents with unique cognitive characteristics. Individuals are guided by the same essential set of socioemotional goals throughout life, such as seeking novelty, feeling needed, and expanding one’s horizons. However, the relative priority of different sets of goals changes as a function of age. Typically, despite being at risk for loss of loved ones, function, finances, and status, older adults endorse better well-being than younger counterparts. This apparent paradox is explained by the Socioemotional Selectivity theory

85, which states that according to the perception of time left to live, an individual’s perceived limitations on time lead to reorganizations of goals thereby prioritizing those with emotional meaning over those that maximize long-term payoffs in the distant future. This is believed to occur through more effective cognitive control over negative affect which reflects in effective emotion regulation mediated by the ventral PFC.

86 However, in the less frequent cases when depression occurs in older adults, it is typically associated with vascular insults that affect the PFC function. Because late onset depression is usually secondary to the loss of coping cognitive mechanisms in the elderly, it tends to be treatment resistant and have poorer outcomes.

Suicide is the most catastrophic outcome of depression and other psychiatric disorders, and is associated with reduced serotonergic neurotransmission, particularly within the VMPFC, including increased expression of serotonin 1 and 2 receptors

87 and binding of the presynaptic serotonin

2 receptor in the VMPFC

88 (for review, see

89). This dearth of serotonin is thought to impair executive function, predisposing patients to become more impulsive, rigid in their thinking, and poorer decision-makers. Deficits in executive function and problem-solving are greater in depressed individuals with a history of suicide attempts or even suicidal ideation compared with depressed controls.

90 Impaired decision making, reflected in poor performance in the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), which is designed to mimic complex and uncertain decision making, is found in individuals with a past history of suicide attempts,

91 in particular, in those that used violent methods.

92 Euthymic patients with a history of suicide attempts showed significant deficits in executive function: impaired visuospatial conceptualization, inhibition, and visual attention (or reading fluency) suggestive of generalized PFC dysfunction, both DLPFC and VMPFC.

93 It is possible that executive function deficits may be more specific to suicidal behavior rather than to any specific psychiatric diagnosis because this observation holds true for suicidal patients with depression, bipolar disorder, and even temporal lobe epilepsy. Last, poor inhibition is found in suicide attempters when compared with patients with only suicidal ideation,

94 and greater cognitive executive function impairments are found in depressed patients with suicidal ideation compared with those without it.

95 However, individuals with a history of suicide attempts show poorer inhibition but better problem-solving ability than suicide ideators.

94 There is evidence that at least a subgroup of suicide attempters have deficits in self-regulation and temporal discounting. Depressed suicide attempters 60 years or older showed deficits in probabilistic reversal learning suggesting that this population makes present focused decisions, ignoring past experiences.

96 In a similar elderly sample, Dombrovski et al.

97 showed decreased temporal discounting in high-lethality suicide attempters compared with low lethality ones.

Anxiety

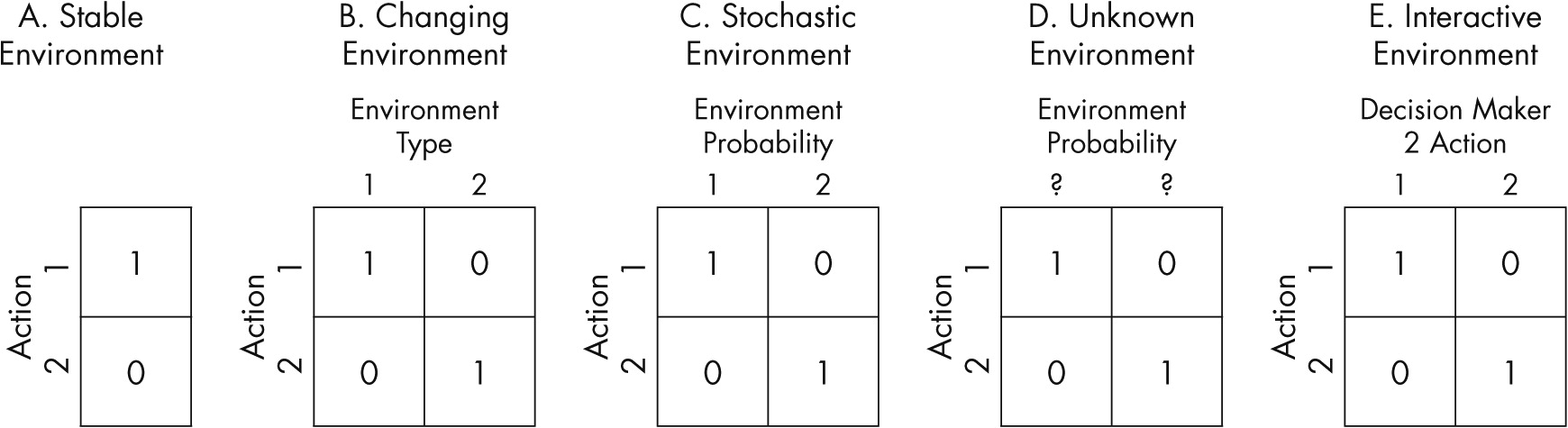

Anxiety is the natural response to risk and uncertainty, both of which are frequently found in everyday life (see

Figure 1). The amygdala plays a central role in mediating an anxiogenic response to unpredictability.

98 Additionally, the insula is a key structure involved in the prediction of risk,

18 and the DLPFC is positively correlated with risk aversion.

99Fear and anxiety are closely related, and share common cognitive and physiological properties.

100 Fear response is evoked by specific stimuli and tends to be transient, decreasing once a threat has dissipated. Anxiety may be experienced in the absence of a direct threat and typically persists over a longer period of time. However, anxiety is commonly conceptualized as a state of sustained fear.

101 Fear conditioning has been a most successful research model to understand the biology of anxiety. Animal and human research on fear conditioning has highlighted the central role of the amygdala in fear acquisition, storage, and expression.

101–103 The amygdala’s projections to different parts of the brain have been associated with specific functions. For instance, projections to the brainstem and hypothalamus mediate autonomic fear expression, projections to the ventral striatum mediate the use of actions to cope with fear,

102 hippocampal projections are involved in contextually dependent expression of fear,

104 and connectivity to the VMPFC is required for inhibition or control of conditioned fear and storage of extinction memory

5,104,105Two principal information-processing biases are characteristic of anxiety: (1) a bias to attend toward threat-related information, and (2) a bias toward negative interpretation of ambiguous stimuli.

106 Anxiety is associated with faster response times when detecting a threat or negative stimuli or identifying a target cued by a threat stimulus, and slower response times when detecting a neutral stimulus or reporting neutral information in the presence of a threat stimulus.

107–109 This attentional bias reflects both facilitated detection of threat-related stimuli and difficulty in disengaging attention from negative stimuli,

107 and seems to be related to both the engagement of preattentive amygdala-dependent threat evaluation processes

110 and impaired prefrontal control mechanisms typically engaged during attentional competition and control.

111 Consistent with this view, high trait anxiety is associated with increased amygdala activity to attended as well as unattended threat stimuli

112 and decreased prefrontal activation under conditions of attention competition,

111,112 even in the absence of threat-related stimuli.

113Anxious individuals unrealistically judge negative outcomes to be more likely than positive ones.

114–116 Higher trait anxiety is associated with heightened amygdala blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD)-responses during passive viewing of neutral faces

117 and a tendency to interpret neutral faces more negatively.

118 For instance, anxious individuals tend to interpret ambiguous emotional facial expressions,

119 face-voice pairings,

120 and homophones

121 as more negative in valence than less-anxious individuals.

Anxiety as a trait has been amply studied in healthy subjects. Trait anxiety, worry, and social anxiety in healthy participants are predictive of heightened risk aversion.

122–124 In turn, heightened arousal to risky choices or increased interoceptive awareness of arousal responses (or an interaction of the two) may lead anxious individuals to be more risk averse. Trait anxiety is also associated with greater susceptibility to the framing effect (i.e., reacting differently whether a choice is presented in terms of gain or loss).

125The circuitry involved in the learning and regulation of conditioned fear is altered in healthy individuals with the anxiety trait and in patients suffering from anxiety disorders. Trait anxiety is associated with heightened amygdala activation as well as elevated fear expression during fear acquisition.

126,127 Anxiety also impairs extinction learning and retention

126–128 as well as the regulation of emotional responses via intentional cognitive strategies.

107,129 Patients with panic disorder show an increased generalization of conditioned fear to similar stimuli.

130 Atrophy of the hippocampus in posttraumatic stress disorder patients suggests that contextual modulation of fear may also be altered in anxiety.

131Although clinical data are still limited,

105 there is clear evidence of negative attentional biases in several anxiety disorders including generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, social and specific phobias, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (for review see

107). Amygdala hyper-responsivity while attending to, evaluating, and anticipating negative stimuli may heighten the cognitive and affective responses to a potential threat in anxious individuals. Thus, the everyday decisions made by individuals suffering from anxiety disorders to avoid exaggerated perceived threats can have a profound impact on the ability to function adaptively.

Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder and schizophrenia share impairments in similar cognitive areas including attention, processing speed, verbal memory, learning, and executive function, although bipolar disorder deficits are usually less severe.

132 These cognitive impairments represent a substantial clinical problem in up to 60% of bipolar disorder patients

133 and can be found in depressed, manic, and mixed episodes as well as in the euthymic state. This pervasive impairment in cognitive function in bipolar disorder suggests it may be a trait marker associated with genetic vulnerability.

A real life consequence of these cognitive deficits is functional impairment in several spheres including independent living, social relationships, and vocational success. For instance, 20% of patients with bipolar disorder are married in contrast to 60% of the general population; approximately 60% of bipolar patients are unemployed compared with 6% in the general population; and 19%−58% are not living independently.

134 These functional impairments are present at the time of the first episode and persist over time.

135In addition to the pervasive alterations in the cognitive sphere, emotion processing is markedly disrupted in patients suffering from bipolar disorder. It has been proposed that central to bipolar disease is a heightened processing of positive emotion regardless of the context.

136 A recent meta-analysis identified significant deficits in theory of mind and emotion processing in euthymic bipolar patients.

137 Emotion processing in depressed bipolar patients appears to involve a partially overlapping neural network with that of major depression, but with distinct roles of the VLPFC and thalamus.

138 Thus, bipolar patients are impaired in their ability to identify other individuals’ emotions and intentions, with a resultant impact on everyday functioning.

Despite these deficits in cognition and emotion processing, the findings on decision making are heterogeneous in bipolar disorder. For instance, manic or hypomanic patients tend to make suboptimal choices in the Cambridge Gambling Task,

139 they are more sensitive to error processing during a two choice prediction task,

140 they show steep temporal discounting,

141 and deficits in response disinhibition and inattention (

142, but see also

143,144). These deficits are not exclusive to mania, since depressed bipolar patients evidence deficits in reward processing, short-term memory, and sensitivity to negative feedback.

145 Moreover, euthymic patients with bipolar disorder also display moderate to severe deficits in a wide variety of executive function measures including category fluency, mental manipulation, verbal learning, abstraction, set-shifting, sustained attention, response inhibition, and psychomotor speed (

146–148, but see also

91,149,150). Furthermore, even first degree relatives of bipolar disorder patients show executive function deficits (i.e., attentional set shifting).

151 In addition to moderate to severe neuropsychological impairments, there seems to be specific cognitive and decision making biases in bipolar patients including impulsivity, exaggerated positive emotion, and deficits in risk assessment and reward processing. The weights of these cognitive and decision-making impairments are evident in the somber functional outcomes of patients with bipolar disorder.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a severe psychiatric disorder that afflicts approximately 1% of the population worldwide. It is characterized by alterations in higher function including thought, perception, mood, and behavior. The majority of people with schizophrenia do not attain “normal” milestones in social functioning, productivity, residence, and self-care. For instance, less than 20% of schizophrenic patients are responsible for their housing, almost 80% are unemployed, and less than 15% are married or in stable relationships.

152 This functional impairment occurs despite adequate symptom control that is attained by 30%−70% of patients. A large body of evidence has demonstrated significant cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia, which is associated with disorganization, negative symptoms, and impaired functional outcome.

153 Information-processing deficits in schizophrenia are described in attention, working memory, inhibition, and context processing.

154 Context-processing deficits are associated with working memory impairments and dopaminergic tone in the PFC (

Table 3).

155 Moreover, both cognitive control and social cognition (e.g., theory of mind) deficits are disease outcome predictors and suitable candidates for therapeutic interventions.

152,156 It is no surprise that this faulty information processing in schizophrenic patients translates into impaired risk assessment,

75,76 reward processing,

157 and temporal discounting.

158,159 The latter are correlated with working memory deficits.

159,160A pervasive clinical challenge in schizophrenia is the elevated comorbidity with substance abuse disorders. Approximately half of schizophrenic patients present a lifetime history of substance abuse disorders,

161 and 75%−90% are current smokers.

162,163 These extraordinary high rates of substance-use comorbidity may be explained by disrupted reward processing.

164 Thus, patients with schizophrenia who are smokers display a stronger subjective response and intensity of demands to smoking than the general population smokers.

165,166 In sum, patients with schizophrenia exhibit global cognitive control dysfunction that is reflected in specific deficits in risk assessment, reward processing, and temporal discounting. These impairments are translated in the devastating functional toll of this disorder.