Dear Sir: Drug misuse is a known risk factor for cerebrovascular disease, especially among young people.

1,2 Cannabis is the most widely-consumed illicit drug worldwide, but it has only occasionally been associated with ischemic vascular events.

1–3 Vasospasm, hypotension, arrhythmias, and vasculitis have been proposed as potential mechanisms.

1–4 We report on a case of recurrent stroke in a young cannabis user.

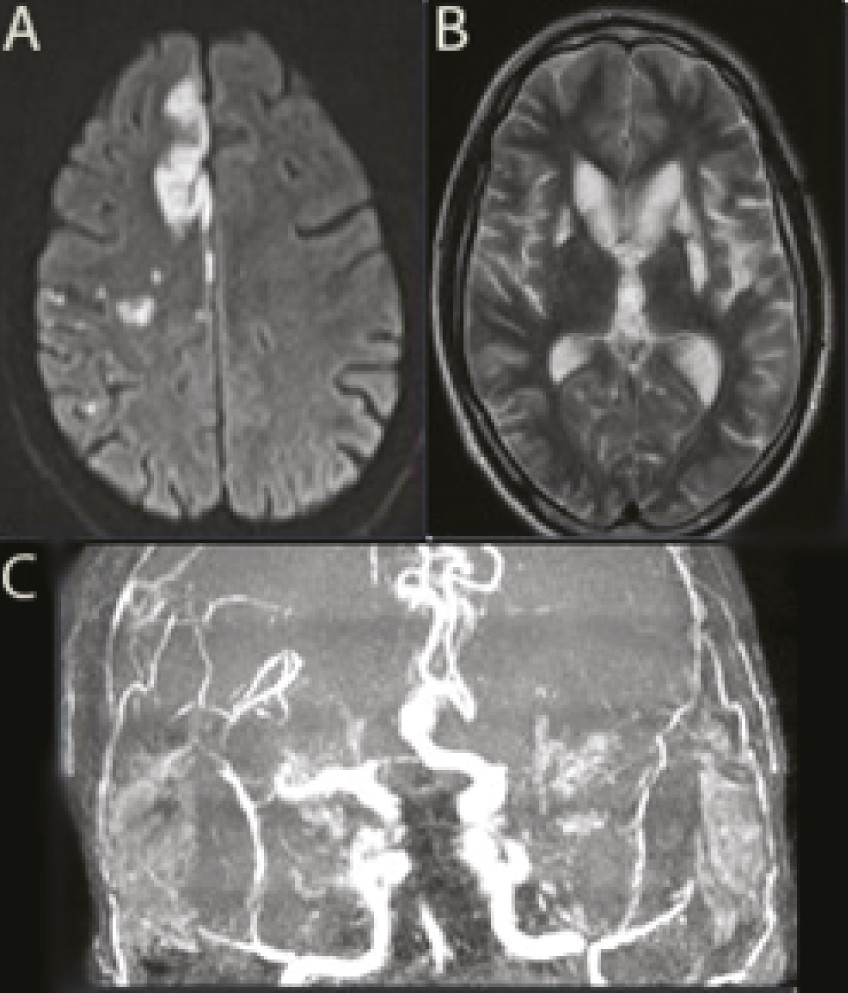

A 27-year-old man, a heavy cannabis user, was admitted in a Stroke Unit in August 2006, with acute right hemiparesis. He did not consume other illicit drugs or medication, and only sporadically consumed alcohol. Computed tomographic (CT) scan showed a recent left basal ganglia infarct. Urine toxicological screening was positive for cannabis and negative for amphetamines, cocaine, and benzodiazepines. Laboratory studies (including biochemistry, infectious serology, prothrombotic, and immunologic studies), carotid and vertebral ultrasound, trans-esophageal echocardiogram (TEE), and Holter were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed 14 cells (75% lymphocytes). Angiography revealed a left middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion. Vasculitis was suspected, and prednisone was started. In February 2007 (prednisone had been suspended in December 2006), he presented with acute-onset of left hemichorea. CT scan revealed a right lenticulostriate infarct. His urine tested positive for cannabinoid. Laboratory studies (including CSF and now MELAS, Fabry and CADASIL genetic testing) did not reveal any abnormalities. TEE suggested the hypothesis of a small patent foramen ovale (PFO). Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed multiple infarcts. Facing the possibility of an embolic source, hypocoagulation was started. Despite therapeutic INR, he suffered another abrupt onset of left hemiparesis, in August 2008. His urine tested positive for cannabinoid. Repeated laboratory studies, CSF, echocardiogram, and Holter were normal. Brain MRI revealed multiple recent ischemic lesions in the right carotid territory and old lesions bilaterally, and MRI angiography showed diffuse irregularities of the anterior and posterior circulation (

Figure 1). No evidence of diffuse atherosclerotic disease was present. At this point, aspirin and prednisolone were restarted, with no repetition of cerebrovascular events.

Effects of cannabis include psychiatric reactions,

2–4 cognitive dysfunction,

4 memory and time-assessment alterations,

4 motor incoordination,

4 poor executive functioning,

4 sedative effects,

4 and cardiovascular changes.

1–4 Ischemic strokes related to cannabis have been reported in the literature;

1–4 however, because of the widespread use of the drug, it is difficult to establish a causal relationship. We believe that the recurrent strokes in this case were associated with the chronic use of cannabis, with vasculopathy being the most likely mechanism. There was no evidence of postural hypotension, and repeated blood pressure measurements on admission were normal. Electrocardiograms and Holter monitoring did not show abnormalities on the three different occasions. Facing the possibility of a PFO, hypocoagulation was started after the second event, and, despite this therapy, the patient suffered another stroke. The involvement of multiple arterial territories and the diffuse irregularities revealed in the MRI angiography suggest the existence of an underlying vasculopathy, toxic or immune-inflammatory. This case report supports a potential risk of stroke associated with cannabis use and suggests that toxicological screening for cannabinoid metabolites should be done in young stroke patients with no known vascular risk factors or evidence of dissection.