Case Report

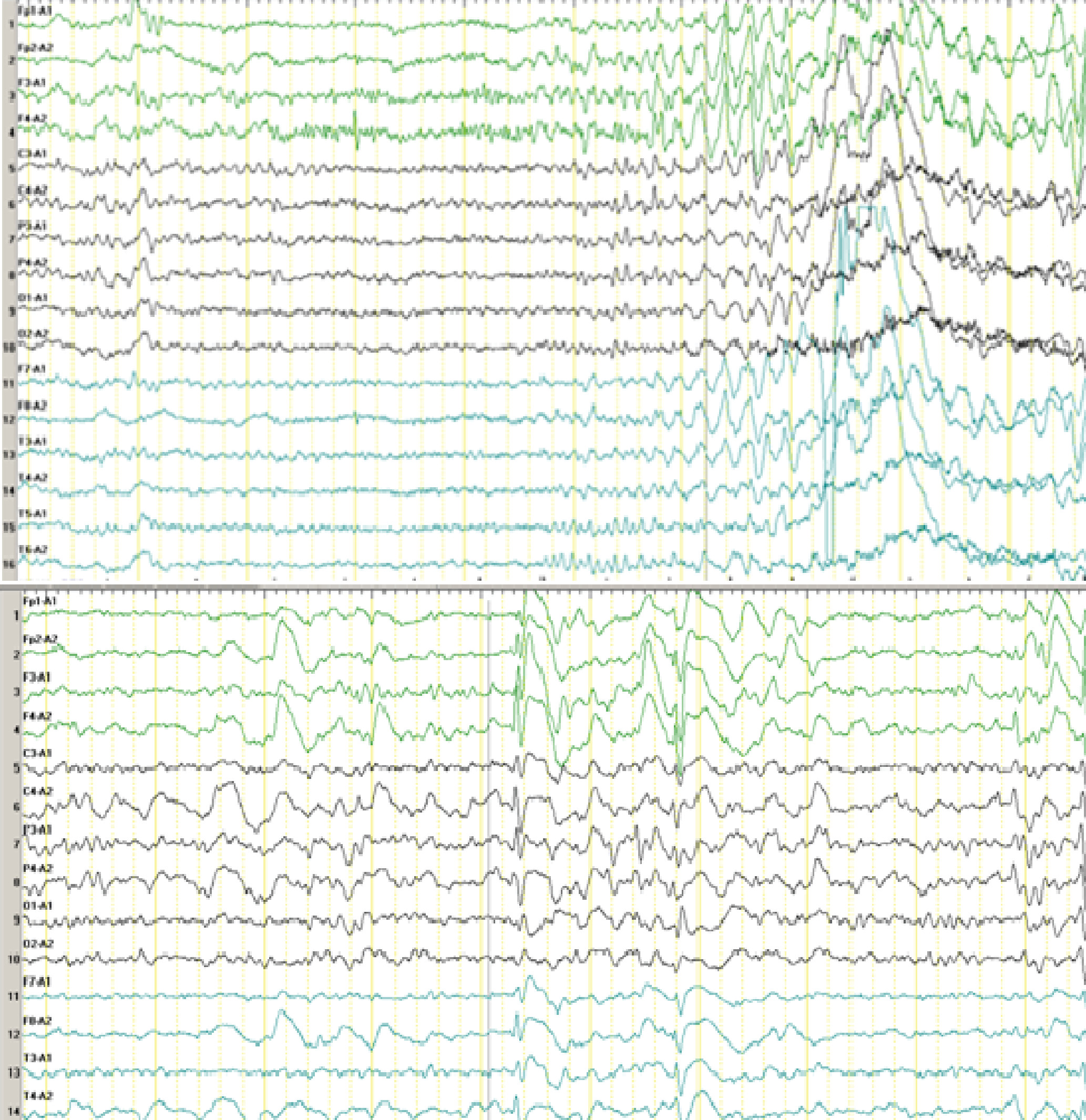

A 7-year-old boy was referred to our hospital with the chief complaint of frequent motor seizures for >3 years, which affected his body on the right side during sleep and were followed by gelastic seizures. The seizures, which lasted no more than 1 minute, occurred up to 39 times per day. The patient experienced his first seizure at age 3 years and 2 months, after his temperature was controlled during a fever. His head deviated to the right side with a gelastic seizure for no more than 20 seconds, and he could not complete his parents’ commands such as picking up the apples on the table and had no response to this request. The patient resumed normal activity with no recollection of the event, and he had no seizures for 1 month. At age 3 years and 3 months, he was admitted to a local hospital for an EEG, and there were four seizures during the 4-hour sleep monitoring. During the seizures, the boy had no response to voice commands, and he had conjugate eye movements, a folded right fist, and an unbent right leg, which lasted nearly 20 seconds. During this time, the boy had a normal temperature. The EEG showed that the origin of the seizures was from the frontal region (

Figure 1).

The patient was born after a full-term pregnancy without any complications and developed normally until the first seizure. His intelligence and physical development were both normal. Moreover, the boy had no family history of seizures and no history of craniocerebral trauma, intoxication, encephalitis, meningitis, or febrile seizures.

At age 3 years and 3 months, the boy was diagnosed with epilepsy and antiepileptic drugs were started. He visited many different hospitals, and he was diagnosed with frontal lobe epilepsy at age 3 years and 10 months. However, different antiepileptic drug therapies, including lamotrigine, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, levetiracetam, and gabapentin, were not effective for him for nearly 4 years.

On the patient’s admission to our hospital, we found no evidence of acidosis or serum electrolyte imbalance. In addition, CSF examination, head CT scans, head MRI scans, head MR angiography scans, and examinations for toxoplasma, rubella virus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes virus were all normal. An examination using the WISC was also normal. Finally, refractory complex partial epilepsy was diagnosed and clonazepam [5-(2-chlorophenyl)-1,3-dihydro-7-nitro-2H-1,4-benzodiazepine-2-1] was added. To our surprise, the boy’s symptoms did not improve; on the contrary, they got worse. The seizures became more frequent during sleep as recorded by nocturnal polysomnography. As a result, clonazepam was stopped 3 days later.

Discussion

Clonazepam is a potent benzodiazepine compound that was approved as an antiepileptic drug by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1976.

1,2 It is effective in myoclonic and generalized absence seizures rather than generalized tonic–clonic seizures, which can actually be exacerbated; therefore, clonazepam is rarely used as a primary antiepileptic drug, although it still has a role as an adjunctive therapy.

3 According to Raspall-Chaure et al.,

4 clonazepam is selected as a first-line drug in severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy, epilepsy with continuous spike wave of slow sleep, myoclonic-astatic epilepsy, and infantile spasms, and is a second-line drug for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy and Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. Benzodiazepines can be used in refractory epilepsy such as partial, idiopathic generalized, and symptomatic/cryptogenic generalized epilepsy.

5 Clonazepam could be useful in children with refractory epilepsy because it may reduce the frequency of seizures, although a high frequency of side effects such as hypotonia, hypersalivation, and bronchial hypersecretion was observed.

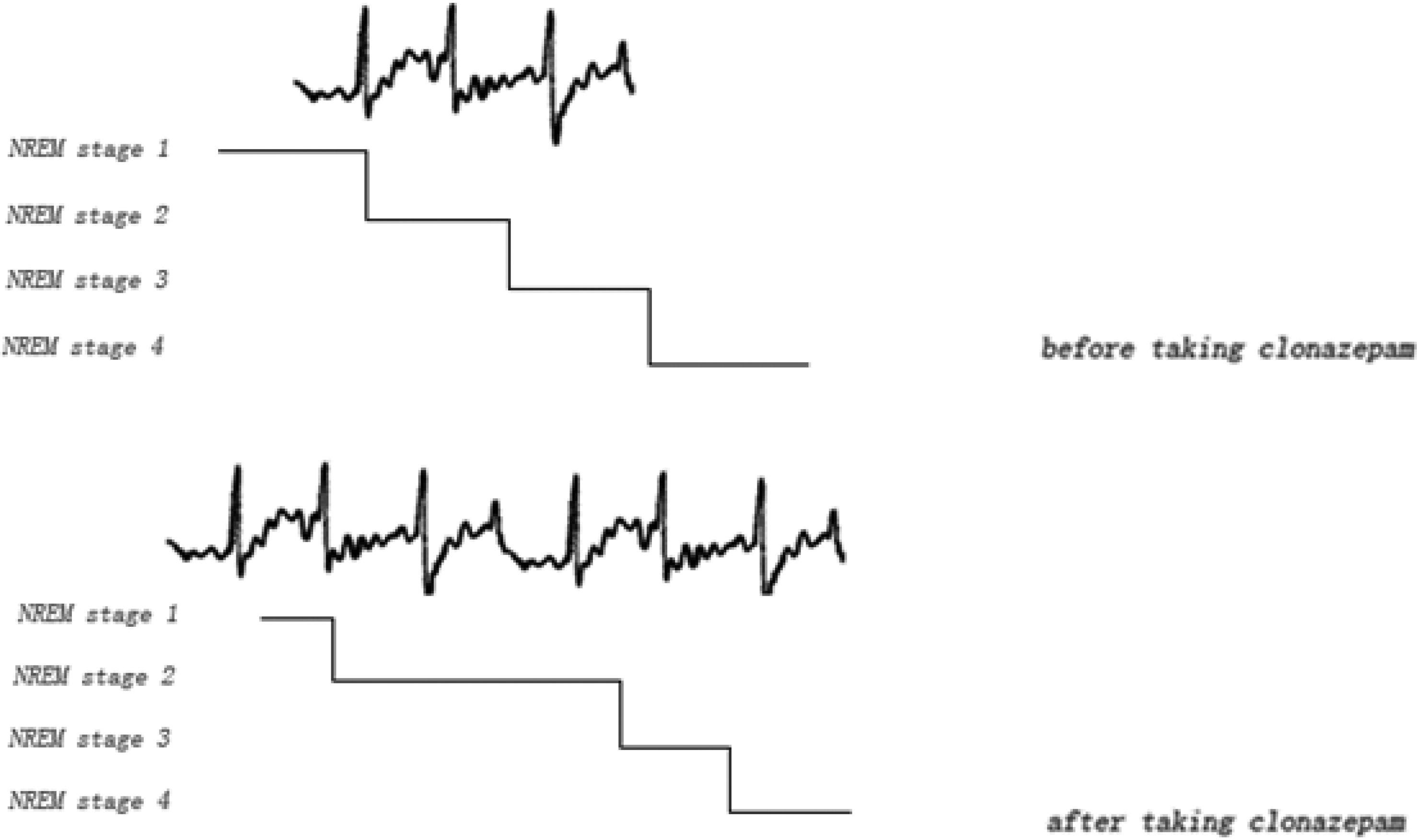

6,7 Moreover, increased total sleep time, sleep efficiency, sleep stage 2, and slow-wave sleep have been shown in patients receiving clonazepam treatment.

8Here we report a 7-year-old boy who was diagnosed with refractory complex partial epilepsy, in which clonazepam was tried after multiple medications and failed to control this type of seizure. We found that seizures became more frequent, not less frequent. By analyzing the polysomnography recordings, we can see that the seizures intensively spread in non-REM sleep stage 2 before the patient took clonazepam. After the patient took clonazepam, the time of non-REM sleep stage 2 was largely prolonged, which contributed to more seizures during sleep. The schematic diagram is shown in

Figure 2.

Clonazepam is a traditional antiepileptic drug and has a long history, but its use is limited by a higher incidence of side effects as mentioned earlier as well as potential tolerance in some patients.

7 However, clonazepam is used in some cases of refractory epilepsy and epilepsy in children because neurologists generally find that seizures during sleep can be controlled by clonazepam, which is effective for seizures with a high frequency. Thus far, we have not found exacerbation of seizures after taking clonazepam due to the lengthening of non-REM sleep stage 2. Antiepileptic drugs affect the structure of sleep. Therefore, we remind neurologists to consider the distribution of ictal discharges in the polysomnography recordings and the effects of antiepileptic drugs on sleep when deciding whether to use these drugs to treat seizures during sleep. Sometimes if we do not think deeply, the measures we take will be just like an old saying in China, gilds the lily.