The DSM-5

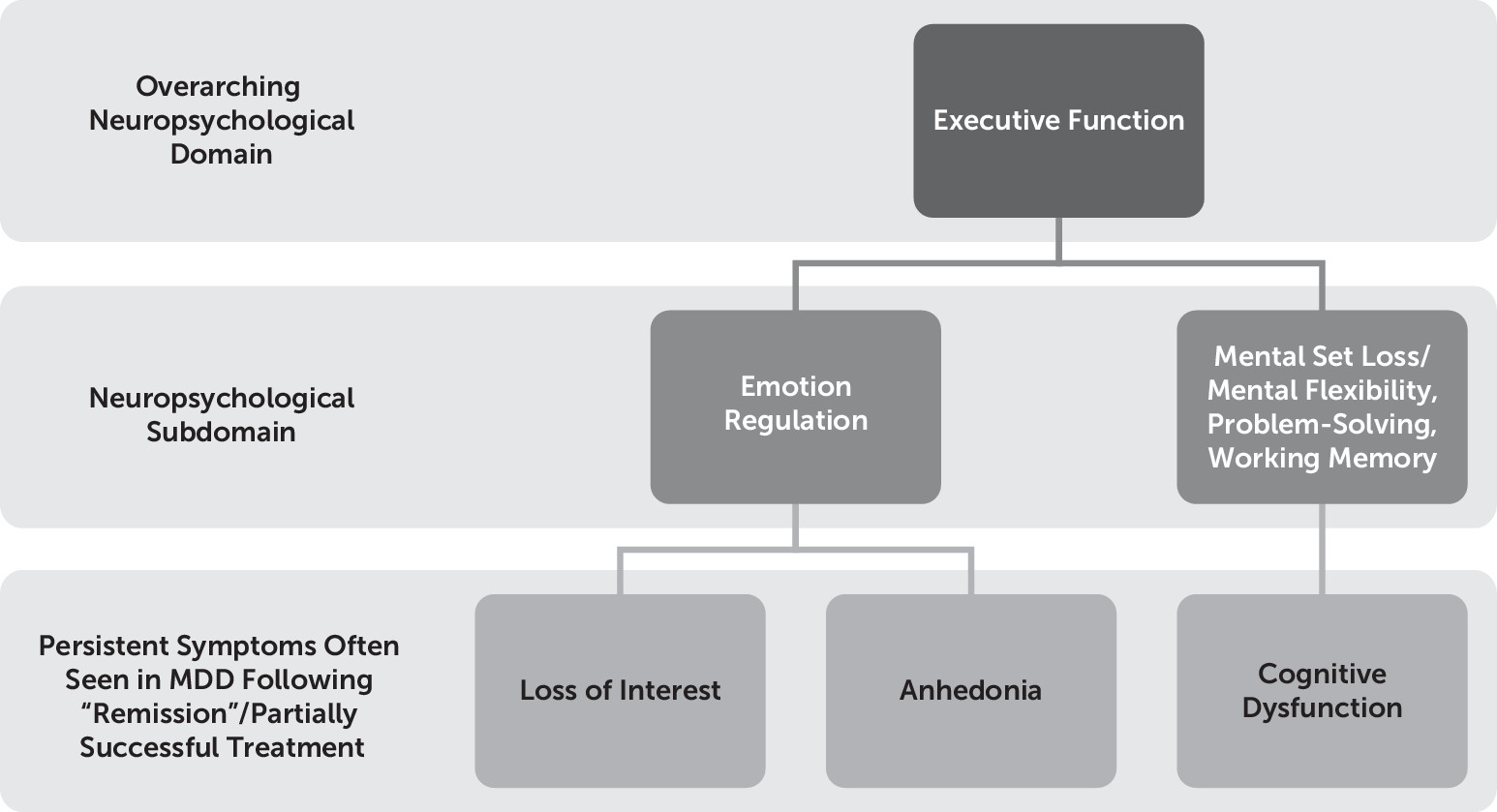

1 identifies cognitive dysfunction (i.e., the “diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day” for 2 weeks) and anhedonia (i.e., the reduced ability to experience positive emotion) as criteria for major depressive episode. We consider these symptoms together in the present study because we hypothesize that cognitive dysfunction, particularly executive dysfunction (an umbrella term used to describe a set of skills—including working memory, abstract reasoning, multitasking, problem solving, and planning—that enable us to learn, make choices, be creative, solve novel problems, and carry out everyday tasks), is related to one’s inability to experience pleasure, given their shared persistent nature following resolution of other symptoms of depression, and putatively shared neuroanatomical correlates owing to an underlying mechanistic relationship between positive emotionality and executive function. Specifically, the following two aspects of executive function are hypothesized here to be subserved by the same prefrontal region, namely, the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPC): 1) mental flexibility/mental set shifting and inhibition (constructs that contribute to the cognitive dysfunction typically observed in major depressive disorder [MDD])

2 and 2) emotion regulation processes (which typically are associated with negative affect and anhedonia)

3 (

Figure 1). Of course, this is not the only region that plays a role in these processes, but it seems to be a key node in both of these processes. Therefore, we hypothesized that endogenous mu-opioid system function in the VLPC may be an important integrative site for these processes, in part given its histological and functional connectivity with the orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex on the one hand, a region known to be key for the subjective experience of pleasure

4 due to its classification as a “hedonic hotspot” and an area dense in mu-opioid receptors relative to some other prefrontal regions, and its dual and distinct role in slightly “colder” executive function processes, such as response inhibition and mental flexibility,

2,5 on the other hand (owing to its collaborative functions with other lateral prefrontal regions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [DLPFC]). First, the construct of cognitive dysfunction and anhedonia are described separately, and then they are integrated.

Anhedonia in MDD

Anhedonia is a key feature of MDD.

8–10 The lifetime prevalence of anhedonia is 5.2%,

11 and recent reports estimate that approximately 37% of individuals diagnosed with MDD experience clinically significant anhedonia.

12 Significant focus has been placed on the symptom of sadness or depressed mood, and certainly the work done to date investigating the neurobiological basis of this symptom in MDD has been fruitful, as all antidepressants on the market tend to reduce the experience of negative emotions. However, anhedonia has only recently begun to be vigorously investigated. For example, the DSM-5 states that individuals meeting criteria for anhedonia may report feeling “less interested in hobbies, ‘not caring anymore,’ or not feeling any enjoyment in activities that were previously considered pleasurable,” and “family members often notice social withdrawal or neglect of pleasurable avocations”

1 (p. 163). This definition is very broad and does not discriminate between a decrease in motivation and a reduction in experienced pleasure, which have been found to be separable phenomena, with differing neurophysiological and neurotransmitter correlates

13,14. “Consummatory” pleasure (pleasure derived

during a pleasurable task) is thought to be mediated by opioid neurotransmission, whereas “anticipatory” pleasure (pleasure derived

before the onset of a pleasurable task) is thought to be mediated by dopamine neurotransmission. Thus, there is significant heterogeneity at the level of symptom definition,

15 which can cause problems when trying to devise treatments for specific symptoms. Certain treatments may affect certain aspects of a symptom (e.g., “anticipatory” anhedonia) and not others (e.g., “consummatory” anhedonia). Current treatments do not adequately address consummatory anhedonia in particular,

16,17 and thus this form of anhedonia should be a target of fervent research, as medications do seem to target anticipatory anhedonia to some degree via dopaminergic and noradrenergic mechanisms.

16As we have alluded to, opioid functioning may play a role in mediating hedonic responses in humans, and top-down lateral prefrontal cortex activity may play a particularly important modulating role on opioid-rich subcortical reward circuitry (e.g., the amygdala and nucleus accumbens). To date, most of the work on the role of opioids in hedonic reactivity has come from animal studies. However, addiction research has lent itself to the study of the relationship between opioid neurotransmission and mood in humans. It is well known, for example, that substances that bind to mu-opioid receptors, such as morphine and heroin, produce feelings of euphoria and also reduce the conscious experience of pain. Furthermore, animal research has also provided us with information regarding sensory pleasure; for example, opioid release and pleasure related to sweet tastes is a well-documented phenomenon.

14 Prior work has also illustrated the role of the opioid system in top-down modulation of the placebo pain response,

18 which arguably has implications for the experience of positive emotions given that pain and pleasure may be opposite extremes on a continuum. Specifically, Zubieta et al.

18 demonstrated that increases in endogenous opioid activity occurring in the DLPFC depended on participants’

expectation of analgesic effects. This suggests that lateral prefrontal cortex activity may play a particularly important role in aspects of cognitively mediated analgesia responses. By extension, analgesia is a construct that is closely related to pleasure and reward, as the absence of pain is generally thought to be necessary, but not sufficient, for the experience of pleasure/positive affect. In this manner, extending the findings of Zubieta et al.

18 by studying the relationship between lateral prefrontal regions and the putative top-down regulation of emotional experience related to analgesia/pleasure in more detail seems important for further delineation of the function of the opioid system in humans.

Overall, it was hypothesized that those same brain regions that mediate the persistence of certain cognitive deficits (i.e., executive dysfunction) in MDD during and following treatment likely also mediate the persistence of affective deficits (i.e., anhedonia) in MDD, despite overall reduction in depression severity following treatment.

In the present study, we aimed to relate opioid functioning in the prefrontal cortex to trait positive emotion in general, extending our understanding of the opioid system’s involvement in analgesia/positive emotion at the human level in a sample of depressed patients, a group of people known to show deficient positive affect and to be at increased risk for pain syndromes and the deleterious effects of stress. Overall, the present project was designed to assess the role of endogenous mu-opioids in higher-order pleasure (i.e., top-down), such as those forms of pleasure involved in our conscious experience of feelings of well-being versus anhedonia.

Regarding the brain region of interest, prior research has strongly implicated the lateral prefrontal cortex in the pathophysiology of depression.

19,20 Specifically, dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal regions have been implicated in eudemonia (i.e., well-being)

10 and anhedonia,

3 respectively, particularly when attempting to use cognitive means to up-regulate or down-regulate positive affect, respectively. Thus, the DLPFC and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC) are promising regions to study in relation to cognition and positive affect. Specifically, given prior work

3 suggesting a role of the VLPFC in positive affect

and cognition (particularly the regulation of positive emotion

3), it seemed reasonable to focus on determining whether this region, and its likely interactions with subcortical structures such as the nucleus accumbens (a key brain region involved in “liking”), is a valid substrate for conceptualizing the co-occurrence of symptoms of anhedonia and executive dysfunction in humans.

Results

Participants with complete neuropsychological data (N=26) versus participants with incomplete neuropsychological data did not differ in terms of age, education, or depression score (all p values >0.10)

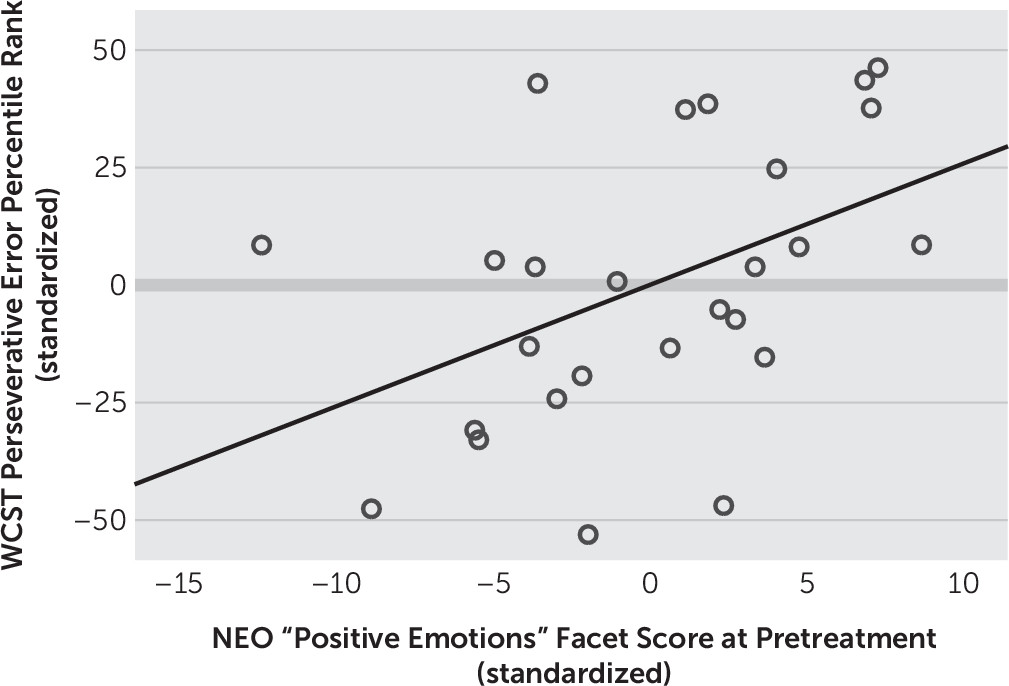

Next, we examined correlational relationships between self-reported positive emotionality, as measured by the NEO Personality Inventory and executive function measured by WCST at baseline (i.e., pretreatment). All aspects of performance on the WCST, a measure of executive functioning, related positively and significantly to positive emotionality as measured by the NEO Personality Inventory. Specifically, fewer total errors (represented by higher percentile scores, r=0.409, p<0.05), fewer perseverative responses (represented by higher percentile scores, r=0.442, p<0.05) (

Figure 3), total number of categories deduced (r=0.421, p<0.05), and fewer number of failures to maintain mental set (r=–0.446, p<0.05) (

Figure 4) were indicators of the greater the individual’s baseline tonic positive emotionality.

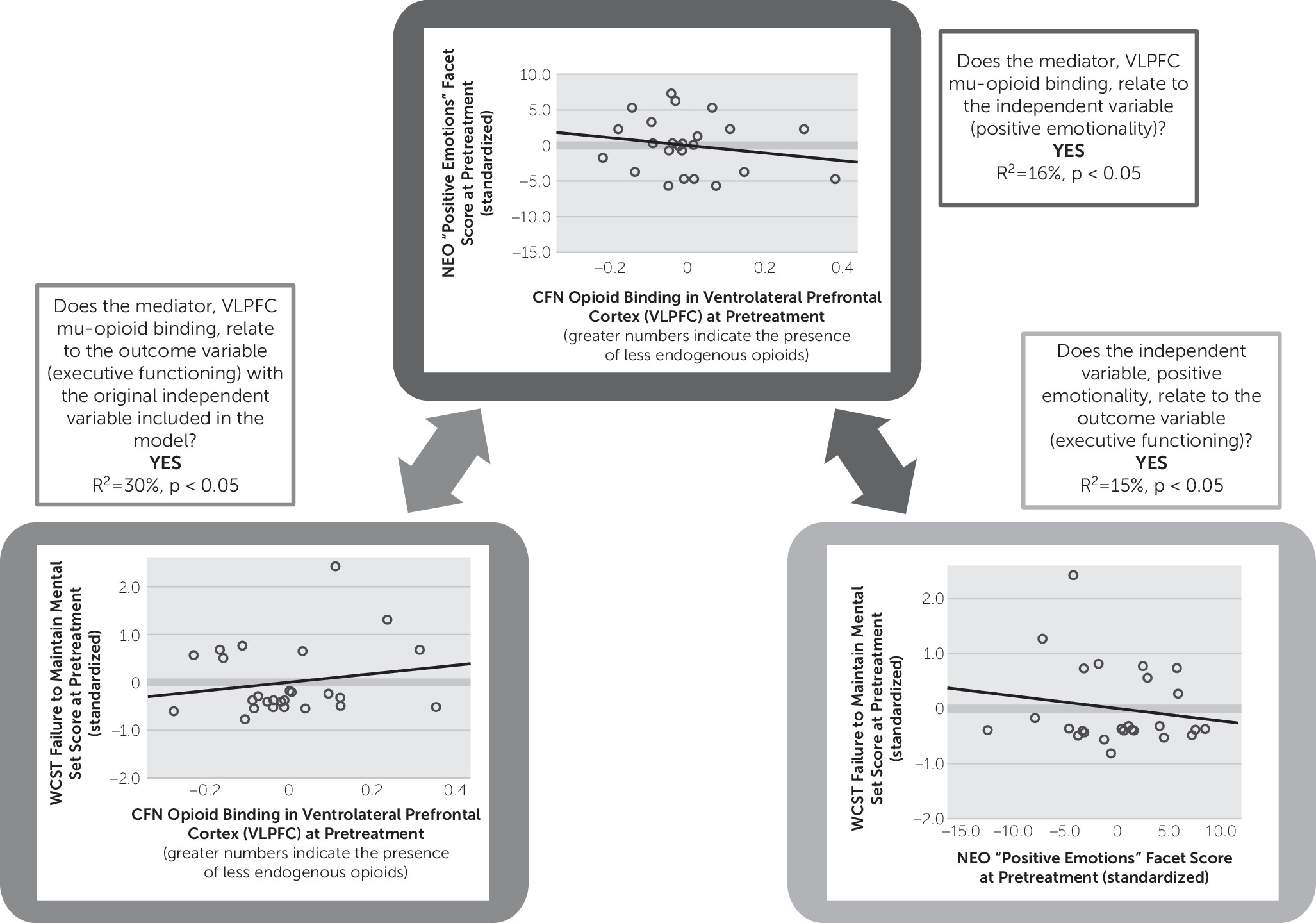

Mu-opioid receptor binding potential in the VLPFC was negatively related to positive emotionality as measured by the NEO Personality Inventory (R

2=15%, p<0.05) (

Figure 4) and executive function as measured by the WCST (R

2=16%, p<0.05) (

Figure 4), suggesting that either lower receptor concentration or, alternatively, higher levels of endogenous opioid activating receptor sites in the VLPFC region are related to greater trait positive emotionality and sharper executive functioning in this sample of MDD patients.

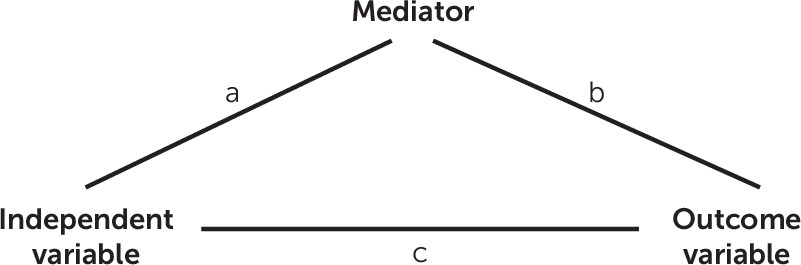

A mediation analysis based on these data collected from the 26 MDD patients with complete neuropsychological data examining the relationship between positive emotion, executive function, and mu-opioid receptor binding potential in the VLPFC showed that when entered into the same model, VLPFC mu-opioid receptor binding potential remained significant (p=0.049), and the NEO “positive emotions” facet became a marginal predictor (p=0.065) of executive function (i.e., WCST mental set loss percentile rank); the overall model was significant (R2=30%, p=0.015). This analysis suggests that VLPFC strongly mediates the relationship between trait positive emotionality and mental set loss/executive function.

We also ran analyses with the HAM-D total score as a covariate in our model to rule out depression severity as an explanatory factor for our mediation results. When the HAM-D total score was entered into the mediation model, the NEO positive emotions score remained a marginal positive predictor of the executive function score (p=0.07), and the overall model remained significant (R2=31%, p=0.04). The VLPFC mu-opioid receptor binding remained a negative and significant predictor of executive function even when the HAM-D score was entered into the model (β=–7.0, p=0.05), suggesting that VLPFC mu-opioid functioning is a strong mediator of the effect between positive emotionality and executive functioning, even when accounting for depression severity.

The VLPFC mu-opioid receptor binding also marginally predicted WCST categories completed (percentile rank) (r=–0.27, p=0.06) and positively and significantly predicted raw errors on the WCST (r=0.28, p<0.05).

No significant relationships were obtained between basal ganglia or amygdala activation and neuropsychological measures.

Discussion

Better performance on the WCST, a measure that taps general executive functioning, related to greater trait positive emotion (i.e., hedonic tone) as measured by the NEO “positive emotions” facet. Specifically, reduced mental set loss, fewer perseverative responses, lower total error rate, and increased total problem solving (i.e., categories completed) related to greater trait positive emotion. The relationship between positive emotionality and mental set loss errors was found to be specifically mediated by mu-opioid receptor availability in the VLPFC. These are the first data, to our knowledge, to directly suggest that the endogenous mu-opioid system in the prefrontal cortex relates directly to positive emotionality and executive functioning in humans with MDD. Furthermore, these findings replicate previous work illustrating a relationship between positive emotionality and executive functioning

35 and add to this literature by providing a plausible neurobiological substrate for this association.

The data acquired in the VLPFC is consistent with its role in affective processes (e.g., emotional experience and emotion regulation) and cognition (e.g., response inhibition, mental flexibility, and complex problem solving). In emotion regulation studies, reduced VLPFC activity relates to better down-regulation of negative emotion

39,40 and resilience against down-regulation of positive emotion.

3 Our results indicate that there is meaningful endogenous mu-opioid system influence in the VLPFC relating to both executive function and positive emotionality. Ultimately, these results extend the work of Kent Berridge and colleagues

4,13,14 on “liking” by suggesting that mu-opioid functioning in the VLPFC relates to complex, conscious positive emotionality at the human level.

Why is there a link between executive functioning and positive emotionality? Or more specifically, what is the real-world significance of the “mental set loss” score on the WCST, and what is its relevance to positive emotionality, and why is this aspect of the WCST mediated by mu-opioid functioning? There is debate in the literature related to whether mental set loss reflects distractibility or mental flexibility (the ability to change ideas). For example, Figueroa and Youmans

41 suggest that the mental set loss score from the WCST is more related to distractibility. They propose that this distractibility may relate to loss of focus on the task because of boredom, mind wandering, or an inability to maintain task-relevant goals. Each of these possibilities is relevant to positive emotionality. A tendency to lose focus or become bored could negatively affect a person’s ability to adequately take in hedonic information when it is presented to them, rendering it impossible to experience subsequent positive emotion. Similarly, mind wandering may also prevent a person from being able to fully relish in a positive experience. Furthermore, an inability to maintain task-relevant goals, or the inability to sustain positive emotion once it is initially generated, may represent another facet of trait-like low positive emotionality/anhedonia.

8Regarding the question of why mu-opioid functioning in the VLPFC would mediate the observed effect, it is important to recognize the unique anatomic and functional characteristics of the VLPFC. The VLPFC is part of the paleocortical aspect of the prefrontal cortex emerging from the caudal orbitofrontal cortex. It is intimately connected with limbic nuclei involved in emotional processing.

42 As such, the VLPFC is intimately connected with more primitive limbic nuclei involved in emotional processing

42 and processes information about basic drives and rewards that inform and direct high-level decision making. Thus, when combined with known conceptions of mu-opioid functioning, namely, the role of mu-opioids in modulating pleasure,

4,14,15 it becomes clear why neurotransmitter function in this region may be a central player in translating/building basic pleasure kernels into higher-order positive emotional states and action tendencies (i.e., via prefrontal decision making and problem-solving processes).

Overall, our results provide evidence that executive function and positive emotionality are linked to mu-opioid functioning in the VLPFC and suggest that deficits in executive functioning may have real downstream repercussions for an individual’s ability to experience positive emotions.

In conclusion, we suggest a circumscribed effect, whereby mu-opioid functioning in the VLPFC in particular mediates the relationship between executive function and positive emotionality. The VLPFC has already been associated with executive function, particularly response inhibition

2 and maintaining mental set.

5 Our prior fMRI work with a clinically depressed adult sample has shown this region to also be involved in the symptom of anhedonia.

3 Here, we have combined these two lines of evidence by presenting data to suggest that these constructs (i.e., executive function and low positive emotionality) are related via mu-opioid functioning in the VLPFC. Overall,

greater mu-opioid endogenous tone (lower binding potential) in the VLPFC mediates the relationship between greater positive emotionality and better executive functioning.Although the opioid theory of depression that was most popular up through the 1950s has been replaced by the monoamine hypothesis of depression,

43 the lack of widespread success of monoamine pharmacotherapy for “treatment-resistant depression” in particular with first-line antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) has prompted the resurgence of consideration of a more

calibrated opioid modulation therapy for MDD. We know that reduced enthusiasm for use of mu-opioid agonists in the treatment of MDD stems from their abuse/addiction potential, but here we suggest that failure in the past of these drugs to be first-line antidepressant treatments may have resulted from the fact that opioid agonists developed in the past were not designed to target specific prefrontal versus subcortical brain regions. Similar to the recent research uncovering the mechanisms of cognitive enhancement of stimulant medication used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,

44 our data suggest that a general acting mu-opioid agonist would be less effective at relieving anhedonic depression because it does not specifically target the VLPFC. Thus, we suggest that MDD characterized by low positive emotion and executive dysfunction is associated specifically with decreased VLPFC mu-opioid tone, and treatments that specifically target mu-opioid functioning in this particular prefrontal region may be more efficacious for this subtype of MDD.

Two recent controlled trials conducted by Fava and colleagues

45,46 utilizing a mu-opioid agonist, buprenorphine, in conjunction with a standard SSRI or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor in a treatment-resistant sample of MDD patients provide supportive evidence. These were treatment studies investigating the efficacy of simultaneous administration of a mu-opioid agonist (buprenorphine) and an antagonist (i.e., to curb the rapid mood elevation associated with the “high” of the drug opposed to its antidepressant effects), with significant reductions in depression scores observed with 1 week

45 and 4

46 weeks of treatment, respectively. These results support the idea that mu-opioids do in fact play a role in modulating depression symptomatology and can effectively be targeted with careful therapeutic approaches.

Limitations of the present study include lack of inclusion of a control group. Furthermore, we did not address treatment effects in this study, though future analyses will address this issue. Additionally, although three brain regions were investigated, only one region showed an effect. Further work is needed to determine whether treatment with antidepressant medication may indirectly regulate endogenous opioid functioning in the VLPFC and other areas of the brain such as the nucleus accumbens, as no studies, to our knowledge, have investigated the potentially procognitive effects of treatment with antidepressant medication.

Overall, this study provides the research community with a better understanding of how mu-opioid functioning in the human brain relates to higher-order cognitive-emotive functioning.