Frontotemporal dementia is the second most common young-onset neurodegenerative dementia, after Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

1,2 The differentiation of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) from young-onset AD has implications for prognosis, genetic considerations, and pharmacological management.

3,4 Although these dementias usually have distinct clinical characteristics and criteria, involving early behavioral and language changes in bvFTD and episodic memory in AD, they can overlap and be difficult to distinguish. Examples include situations in which there is prominent memory impairment in bvFTD

5,6 and in which there are neuropsychiatric features early in the course of AD.

7,8 The overlap of clinical symptoms and the lack of definitive biomarkers confound the problem of differential diagnosis. There is clearly a need for an effective clinical test that can distinguish bvFTD from AD early in the course.

Differences in emotional or autonomic state in these two dementias can serve as the basis of a clinical test. Given mesiofrontal and anterior temporal pathology, emotional blunting is among the earliest and most characteristic features of bvFTD,

9,10 and bvFTD patients have prominent impairments in empathy and sympathy.

2 They may have particular problems in recognizing emotions with a negative valence as opposed to a positive valence.

11,12 In sharp contrast to bvFTD, patients with early AD can have increased emotional reactivity and anxiety.

13,14 Anxiety and an associated heightened sympathetic state may be particularly associated with young-onset AD

15,16 and the first stages of the disease.

17,18Skin conductance levels (SCLs) reflect autonomic and emotional tone and could be a good clinical test for differentiating between bvFTD and AD early in their course. SCLs are a direct measure of ongoing, tonic sympathetic activity and a readily accessible psychophysiological index of emotional tone. Our prior research has shown that patients with bvFTD, compared with those with AD and healthy controls (HCs), have decreased resting SCLs, which correlate with emotional blunting. In addition, their average SCLs may be more likely to be abnormal than the more commonly assayed peak, phasic skin conduction responses to discrete events.

19 In contrast, patients with AD may have increased sympathetic tone, possibly from retained insight or decreased sensorimotor gating associated with AD pathology in the entorhinal cortex.

20This study investigated average SCLs as a measure of emotional tone during video and audio presentation of real-life vignettes among patients with bvFTD and AD compared with HCs. Impairments on psychophysiological measures have varied with the valence (positive or negative outcomes) and emotionality (present or absent emotional paralinguistic cues) of stimuli.

21,22 Investigating SCLs in response to scenarios varying in valence and emotion builds on our prior research showing baseline resting SCL differences between bvFTD and AD.

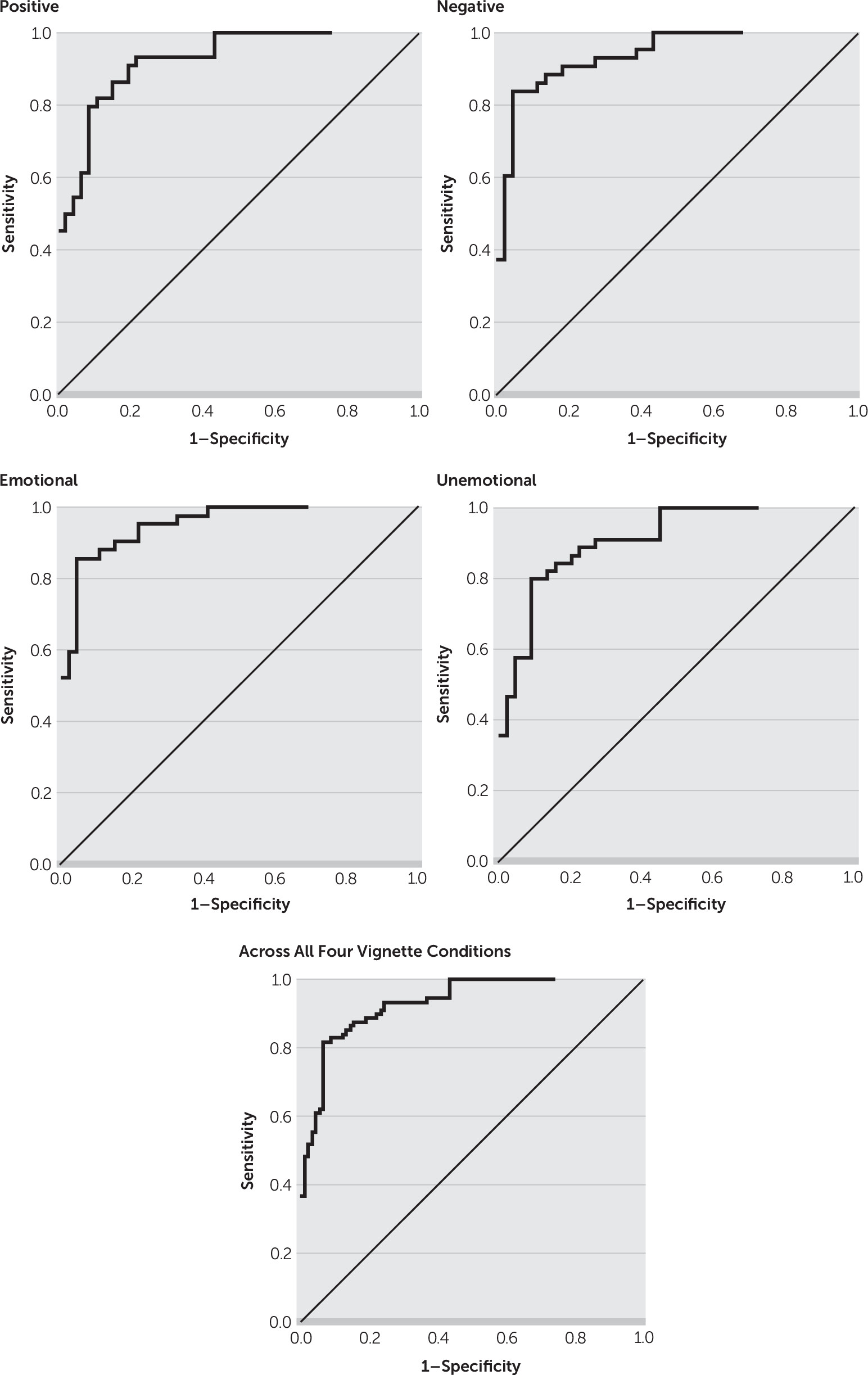

19 In order to determine goodness of the SCLs as a predictive test for the binary classification of bvFTD versus AD, we determined the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (auROC) for mean SCLs. We hypothesized that the bvFTD patients would have significantly lower SCLs, particularly in response to negative or emotional scenarios, and that the AD patients would have heightened SCLs in response to these vignettes. SCLs thus should distinguish the two dementias.

Discussion

BvFTD and AD, the two most common neurodegenerative dementias of the presenium, are easily distinguished with SCLs, a measure of sympathetic and emotional tone. Patients with bvFTD have prominent emotional blunting,

24 and those with early AD may be prone to anxiety and increased emotional reactivity.

15 Using this distinction, this preliminary study shows that SCLs in response to emotional vignettes can differentiate patients with bvFTD, who have low SCLs, from those with AD, who may have high SCLs, at a cutoff of ≤0.773 μS with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 96%. Presenting an emotional scenario to patients with these young-onset neurodegenerative dementias while measuring SCLs is a promising, clinically accessible measure for differentiating bvFTD from AD.

The correct diagnosis of bvFTD or young-onset AD is critical not only for clinical management but also for clinical trial enrollment, genetic analysis, and the understanding of these disorders.

3,4 The differential diagnosis may be difficult when the presentations vary from the established behaviorally predominant criteria for bvFTD

2 and the cognitive features and criteria for AD.

25 Clinicians may misdiagnose bvFTD as AD in the presence of significant deficits in episodic declarative memory,

5,6 which is relatively spared in Consensus Criteria for bvFTD.

2 Conversely, clinicians may misdiagnose AD as bvFTD in the presence of agitation or aggression, hallucinations, or delusions,

7,8 particularly early in the course.

In one large neuropathological study, 22% of clinically diagnosed bvFTD patients were found to have AD on autopsy, having been misdiagnosed because of the presence of early neuropsychiatric symptoms.

7 A third risk for misdiagnosis is the occurrence of an AD frontal variant, best characterized as the “behavioral/dysexecutive” variant of AD, a form of AD that often meets Consensus Criteria for clinically probable bvFTD.

26 Finally, there are no definitive clinical tests for these disorders. Early in the course of bvFTD, fluorodeoxyglucose PET scans can be normal.

27 In AD, amyloid PET may be costly and fail to correlate with the presence of disease state, whereas tau PET is not yet clinically available.

A readily accessible, noninvasive test of tonic emotional state, such as SCLs, can effectively discriminate between bvFTD and AD. Emotional blunting and related deficits characterize patients with bvFTD early in their course and correlate with their mesiofrontal-limbic and associated anterior insular and temporal pathology.

9,10 Patients with bvFTD have impairments in emotion recognition and understanding;

12,28–31 empathic concern;

32 emotion regulation;

33,34 and affective theory of mind, or the ability to infer the emotions and feelings of others.

35–38 In contrast, patients with mild AD or mild cognitive impairment due to AD can have increased anxiety, emotional reactivity, or even affective disturbance, reflecting the beginning stages of their disease.

15,18,39,40 These symptoms in AD may reflect the presence of the earliest Alzheimer’s pathology in the entorhinal cortex, with consequent impairment in sensorimotor gating.

20Although they did not have statistical significance, the largest auROC group differences occurred with emotional presentations. Valence represents the positive versus negative significance of an emotional presentation, and emotional intensity corresponds to the paralinguistic and prosody cues that convey emotion. It is not surprising that the emotional presentations showed the largest discriminability in SCLs between the patients with bvFTD and those with AD.

This study has limitations. First, the study included a relatively small number of participants, which raises concern for sampling bias or a lack of representativeness of the bvFTD and AD patients. The findings showing the value of SCLs for the differential diagnosis of these two dementias need replication in a larger investigation. Second, all the bvFTD and AD diagnoses were clinical; there was no neuropathological verification of the diagnosis. Third, there were no statistically significant differences across valence and emotional stimulus categories. Although the methodology did not show statistically worse SCLs for emotional versus unemotional presentations between bvFTD and AD, the fact that the largest auROC group differences occurred with emotional presentations supports the main hypothesis as well as the potential value of SCLs in differentiating these two young-onset dementias. Finally, the emotional presentations included video presentations of an actor demonstrating behavioral cues of emotion, whereas the unemotional presentations involved projecting a static, neutral portrait of the actor. Despite this design, there were no significant ANOVA differences when we compared the effects of emotional versus unemotional presentation on the SCLs.

In conclusion, SCL differences can be a simple clinical test for distinguishing patients with early bvFTD from those with early AD, particularly of young onset. SCLs are readily available, inexpensive, and noninvasive measures of emotional state, which is blunted in bvFTD and often exaggerated in early AD. Further research is necessary to corroborate these findings in a larger sample of participants with these dementias.