Subacute cognitive disorders are frequently encountered in clinical practice, and many pathologies result in such presentations. Consequently, prompt and precise etiologic diagnosis is necessary because, in some cases, introducing treatments may reverse or prevent further progression of cognitive impairment.

The differential diagnosis of subacute cognitive disorders is broad and requires careful consideration. Among the causes of such disorders are: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a brain disorder resulting in a rapidly progressing dementia syndrome, myoclonus, psychiatric disorders, and visual hallucinations. Other etiologies include toxins and vitamin deficiencies, Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, psychiatric pathologies (e.g., bipolar or unipolar disorder and chronic psychosis, dissociative or nondissociative), and epileptic syndromes and nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Moreover, autoimmune encephalitis can cause cognitive dysfunction, often with co-occurring depressive syndrome, anxiety, and irritability (

1). Patients with infectious encephalitis may present with symptoms of cognitive dysfunction as well.

Here, we present a case of neurosyphilis in an HIV-negative male patient, with discussion of clinical manifestations and neuroimaging modification.

Case Report

A 42-year-old left-handed Caucasian man was admitted to a neurology department with behavioral and cognitive symptoms. He completed 12 years of education and worked as an assistant manager in an insurance company. The patient lived with his male partner. His medical history included a nondocumented case of roseola in 2015, and he was in an automobile accident in March 2016 without head trauma.

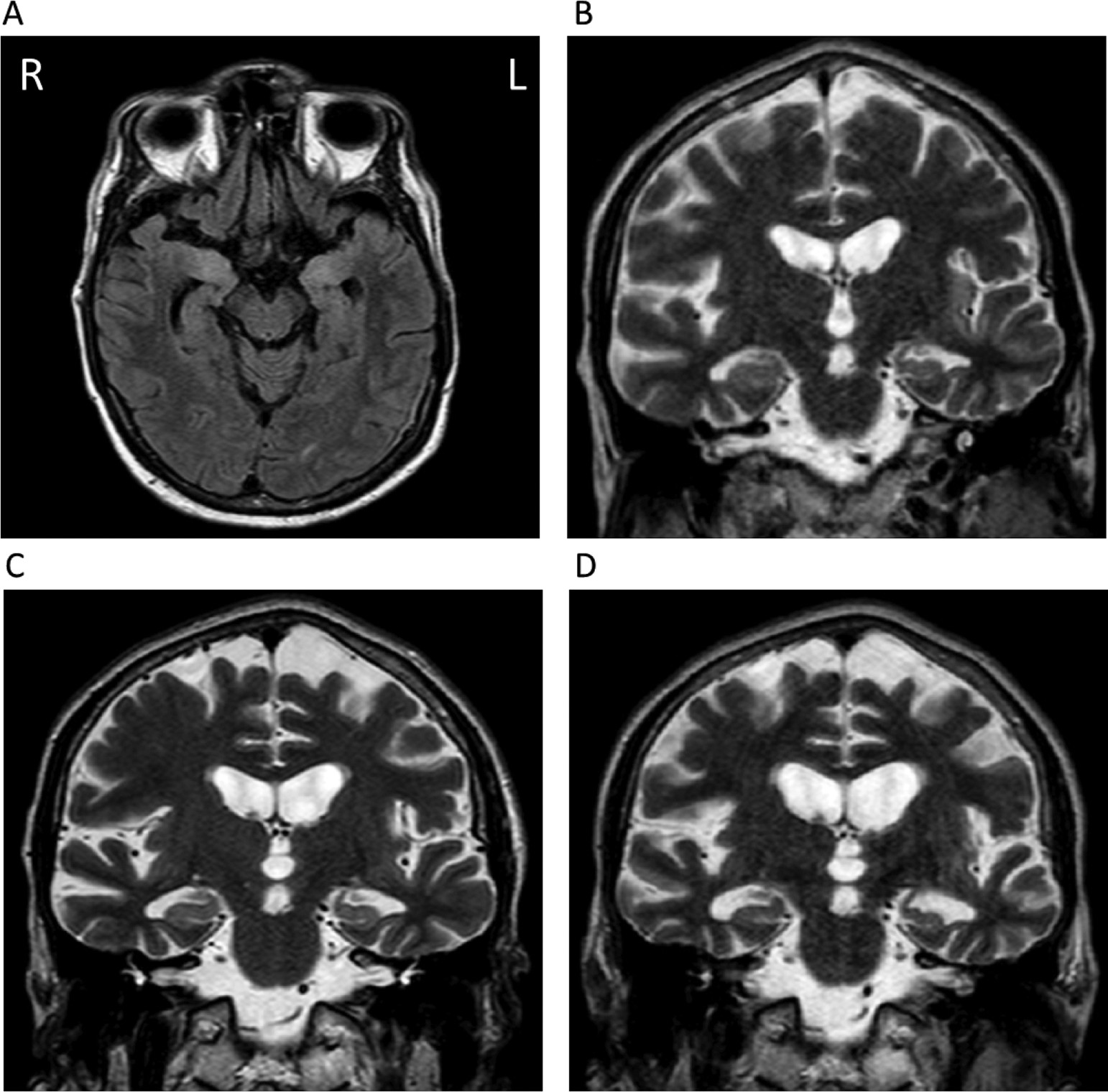

The patient’s onset of depressive symptoms was in March 2016. His irritability and aggressiveness became progressively worse. In August 2016, he presented with dysarthria and experienced difficulty finding words. At the end of 2016, he presented with episodic memory impairment associated with topographic memory dysfunction. A brain MRI (T

2, fluid attenuated inversion recovery, and diffusion-weighted imaging) showed hyperintense signals in the left insular, medial temporal, and bilateral thalamic regions (

Figure 1). A lumbar puncture revealed a protein of 1 g/l and six leukocytes/mm

3. EEG revealed left fronto-parietal focal involvement without epileptiform activity. Anti-Hu, anti-Yo, anti-Ri, anti-Ma2, anti-CV2, antiamphiphysine, voltage-gated potassium channel-complex, and anti-

N-methyl-

d-aspartate receptor antibodies were normal. Polymerase chain reaction for cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2), varicella-zoster virus, and enterovirus revealed negative findings. Serologies for Lyme disease, HIV-1 and HIV-2, and viral hepatitis B, C, and E were also negative. Thoracic-abdominal-pelvic computed tomography, whole-body positron emission tomography, and testicular ultrasound revealed no abnormalities.

A working diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis prompted treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin. Treatment with sodium valproate (1,500 mg/day) combined with paroxetine, risperidone, and oxazepam was started. Despite treatment, his condition continued to deteriorate. He was transferred to our department in January 2017.

Another neurological assessment was conducted. The patient’s Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) score was 12/30. His language and speech were impaired, and he still experienced difficulty with words as well as phonemic and verbal paraphasia and semantic memory impairment. While reading, he exhibited perseveration, phonemic paralexia, and slower speed. His comprehension was preserved. His score on the Dubois (

2) five-word test was 4/10.

He demonstrated problems with social behavior. For example, he entered the rooms of other patients without invitation. His contact was marked by aspontaneity, and he was unable to return to emotional resonance with his interlocutor.

Another brain MRI was performed and revealed hyperintense areas in the medial temporal regions on fluid attenuation inversion recovery sequences. Progression of medial temporal atrophy was observed on serial imaging over a 6-month period (

Figure 1).

Extended video-EEG revealed diffuse brain involvement, predominantly fronto-temporal and asymmetric activity that was sharper over the left hemisphere, which persisted during wakefulness and sleep. No epileptiform abnormalities were identified.

The patient’s general laboratory workup (complete blood count and liver, renal, and electrolyte evaluation) was normal. Antinuclear, anti-extractable nuclear antigens, anticardiolipins, antibeta-2 glycoprotein 1, anti-DNA, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. CSF protein level was 0.8 g/l, with 71 leukocytes/mm3, predominantly lymphocytic (51/mm3). There were more than 10 oligoclonal bands. Intracellular and antimembrane onconeural antibodies in the blood and CSF were not identified. Syphilis treponema pallidum hemagglutination (TPHA) assay and venereal diseases research laboratory (VDRL) tests were positive for disease in the patient’s blood (VDRL >32 and TPHA >5120) and CSF (VDRL 4 and TPHA >5120).

The diagnosis of neurosyphilis was made, and antibiotics were introduced (penicillin G sodium, 5 million IU, four times per day). One day before the start of antibiotic therapy, a bolus of corticosteroids (50 mg of prednisolone) was started to prevent Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. The treatment was continued for a period of 14 days. The patient’s partner was notified of the neurosyphilis diagnosis after the patient provided consent. Counseling was offered to the partner. By the end of the treatment, the patient showed improvement in temporo-spatial orientation, but other neuropsychological impairments, as well as limited functional independence, remained.

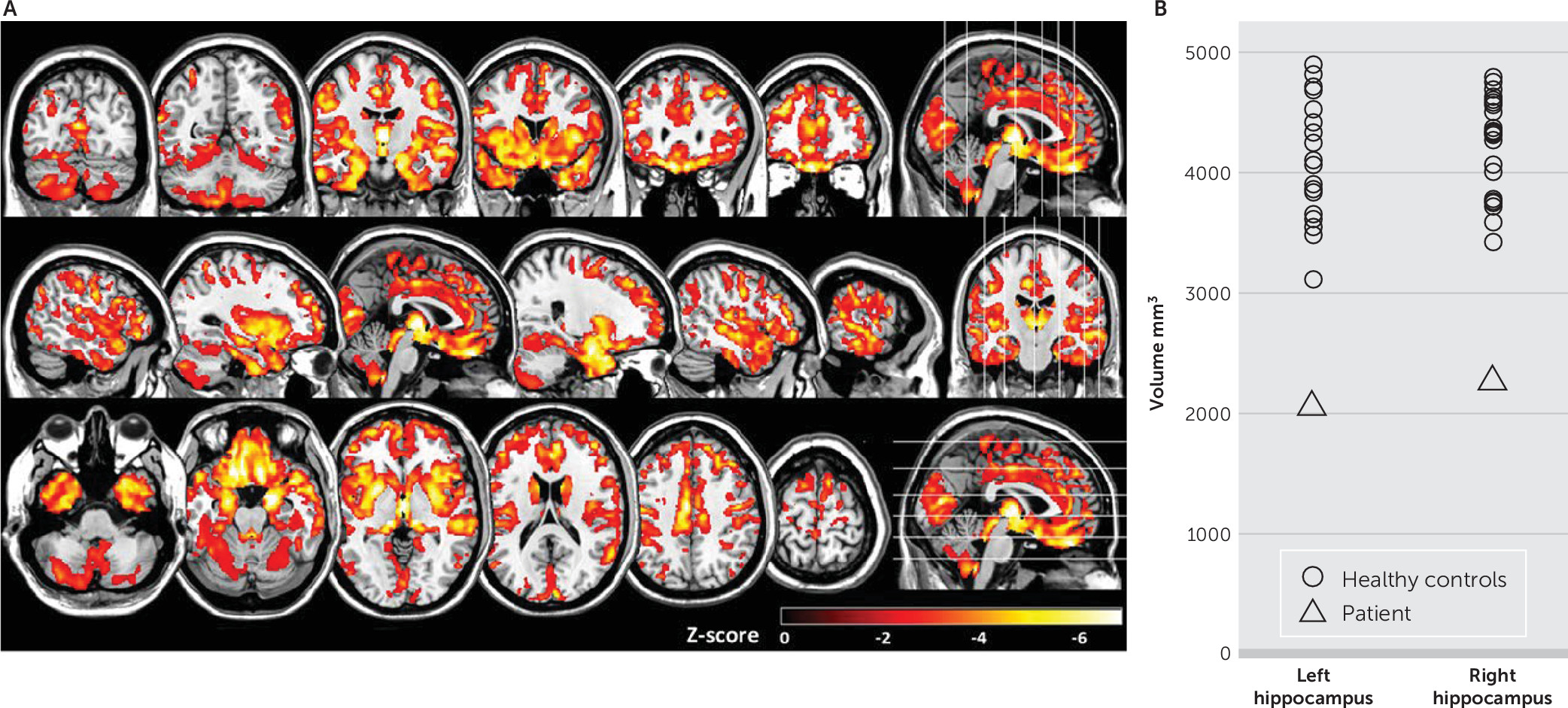

To better characterize the neuroanatomic progression of illness between January and August 2017, MRI structural analyses were performed. A diminution of 6.22% of brain volume was estimated with Siena (

3) (FMRIB Software Library, Oxford, United Kingdom [

4]). This last MRI was compared with images from 20 healthy control subjects (females, N=11; males, N=9; mean age, 42.4 years [SD=3.4]) from the Online Aerospace Supplier Information System database (

5). A z-score map of gray matter density was determined with voxel-based morphometry (SPM version 12, London). General atrophy was revealed in the patient when compared with healthy control subjects, particularly in the amygdala, thalami, and frontal and temporal lobes (

Figure 2A). A segmentation of the hippocampus was also performed using FIRST (

6) (FMRIB Software Library, Oxford, United Kingdom), which revealed significant atrophy in the patient (left hippocampus: control group: 4,126 mm

3 [SD=495], patient: 2,065 mm

3, z score=−4.16; right hippocampus: control group: 4,202 mm

3 [SD=418], patient: 2,270 mm

3, z score=−4.62) (

Figure 2B).

Discussion

Neurosyphilis can occur at any time during the progression of syphilis (

7). Early-stage infection affects the CSF, meninges, and blood vessels, which may result in asymptomatic neurosyphilis, symptomatic meningitis, meningovascular syphilis, and sight and hearing impairment. Late-stage infection affects brain and/or spinal cord and may result in general paresis and/or tabes dorsalis (

8).

Behavioral and cognitive disorders in patients with neurosyphilis have been long reported. Conventionally, these disorders have been grouped under the terms “syphilitic dementia” or “general paresis of the insane.” A subset of patients develop secondary psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, mania, or psychosis. In the last stage of the disease, patients may have seizures or became incontinent or immobile. Additionally, frequently reported are symptoms of Argyll Robertson pupil, facial or limb hypotonia, and intentional tremors of the face, tongue, and hands. In the last stage of the disease, patients may have seizures or became incontinent or immobile (

7,

9).

Our patient had severe memory impairment consistent with the neuroanatomical pattern of brain damage produced by his neurosyphilis. Neurosyphilis with limbic expression usually presents as a progressive dementia that occurs 10–20 years after the primary infection (

10,

11). However, cases of early-stage neurosyphilis with initial neuropsychiatric features, similar to those experienced by our patient, have been reported. Fargen et al. (

12) reported cognitive impairment, worsening over 2 months, and seizures, characterized by the phenomenon of déjà vu, in a male patient. He was treated for syphilis 1 year prior to this presentation, with complete resolution of symptoms after treatment, although cognitive impairment was not specifically addressed. The investigators also identified 156 cases of cerebral syphilis through a systematic literature review, among whom 27 presented with mental (psychiatric) impairment without further specification. In a retrospective study of 116 cases of syphilitic dementia, Zheng et al. (

13) reported that the diagnosis of neurosyphilis was not initially suspected in 36.2%. Diagnostic delay ranged from 1 to 24 months. Behavioral disorders, including emotional disturbances, changes in personality, and behavioral disturbances, were the main reason for hospitalization. Delusions (present in 38.79%) and hallucinations (present in 12.93%) were the principal psychiatric symptoms. Thirty-seven patients had psychosis or severe cognitive impairment. There was no comorbidity with HIV infection. Neuropsychological impairments were present in most patients. The average MMSE score was 14.7 (SD=3.2), with a range of 3 to 19. The mean age was 45.6 years (SD=5.8) for men and 50.2 years (SD=9.6) for women. A similar clinical profile was observed in our patient, with emotional and behavioral disturbances consistent with severe atrophy found in regions involved in emotional processing (i.e., the amygdala, anterior cingulate, and prefrontal cortex). Consistent with prior reports (

14–

16), our patient had atrophy in the frontal and temporal lobes as well as in the hippocampi. Similar to our patient, Kodama et al. (

14) also noted the persistence of clinical symptoms in two patients with severe temporal and frontal atrophy at the time of treatment.

In patients like the one reported here, treatment of both the spirochete infection and the psychiatric and neuropsychological manifestations of neurosyphilis is required. Psychiatric symptoms cause anxiety for patients and their families. Social cognition difficulties secondary to these manifestations can persist despite optimal treatment (

17,

18). Our patient showed impaired social behavior and difficulty with emotional resonance with those around him. Contact improved after 10 days of hospitalization.

Rehabilitation and cognitive remediation is necessary in patients with cognitive sequelae of neurosyphilis. However, the few studies that have addressed neuropsychological assessment of patients with cognitive impairments due to neurosyphilis are silent on this approach to treatment of this condition (

13,

19). The absence of literature describing cognitive rehabilitation for persons with neurosyphilis may be related to a presumption that cognitive impairments due to such infections remit with antibiotic therapy (

20). However, a systematic review of this topic concluded that the available evidence is insufficient to confirm the long-term beneficial effects of penicillin on cognitive impairment due to neurosyphilis (

21).

Monitoring, both clinical and laboratory, constitutes an essential element of patient care. Recent national guidelines in the United Kingdom recommend that monitoring start at 3 months, with follow-up at 6 and 12 months, then every 6 months until resolution of the abnormalities is achieved. A fourfold increase or more of the venereal disease research laboratory test titration constitutes a marker for treatment failure or reinfection (

22). A fourfold decrease in titration at the start of tracking correlates to future resolution of biological abnormalities in the CSF (

23).