Brain-stem lesions, including those in the midbrain, are known to cause hallucinatory delusions (

1–

3). However, to our knowledge, there have been no reports of such cases occurring with symptoms limited to delusions without hallucinations. Here, we report a case of a minor midbrain lesion in a patient who presented with delusions without hallucinations.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Shinoda General Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and the patient’s family in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

Case Report

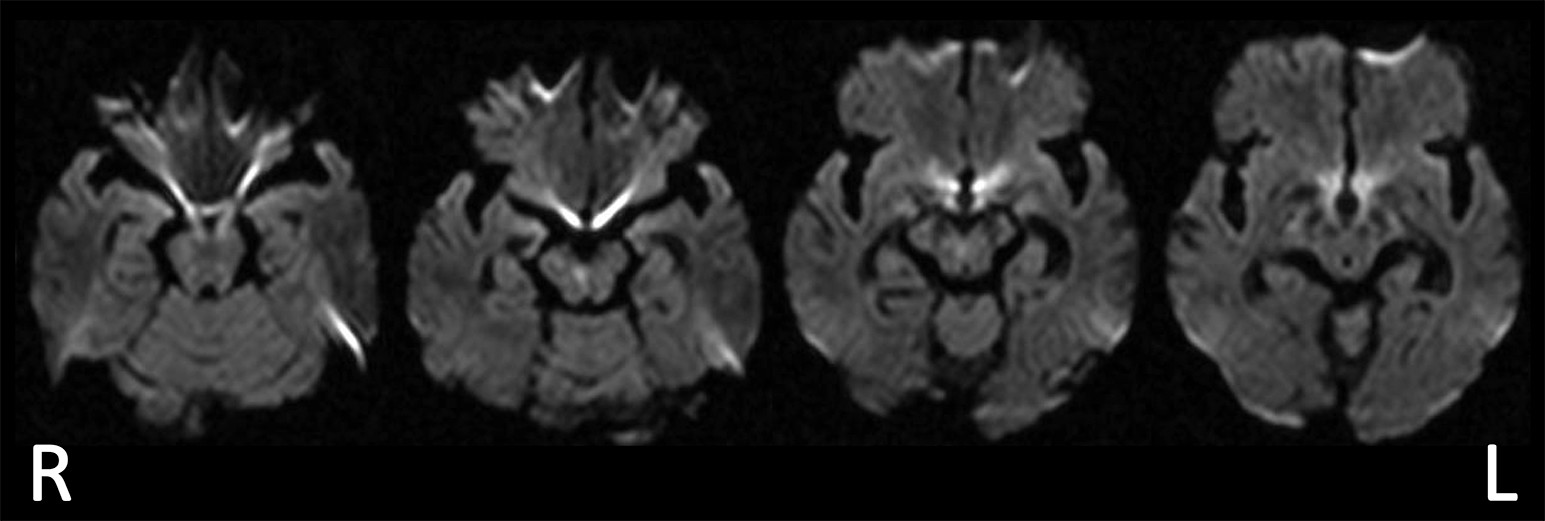

A 77-year-old, right-handed man who complained of problems with articulation, walking, and diplopia was admitted to the hospital. The patient had 12 years of education and no past history of mental or neurological disorders. Three weeks after admission, he requested rehabilitation and was transferred to our facility. Neurologically, he presented with right-medial longitudinal fasciculus syndrome, bilateral cerebellar ataxia in both arms and legs (more notable on the left side), cerebellar dysarthria, rapid speech, and micrographia. No other neurological abnormalities were found. Head diffusion MRI revealed an infarct in the lower part of the midbrain (

Figure 1).

At each therapy session, the patient expressed the following complaints to the therapist: “Someone deleted the address book in my Smartphone”; “Someone will steal my money and kill me, so I must die”; and “My wife is having an affair.” None of these claims were true, and the therapist pointed out their irrational nature, but the patient refused to agree. He also made comments suggestive of a depersonalized state, such as, “I feel like I am in space—this is not reality”; and “It feels like this is not my world.” No visual, auditory, or tactile hallucinations were observed, nor were depressive or sleep-wake disorders.

Several neuropsychological tests were applied in order to assess the patient’s general cognition, general attention, hemispatial neglect, and frontal-executive function. General cognition was evaluated with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (

4), while general attention was tested with the digit and spatial span tasks of the Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised (

5). Hemispatial neglect was examined with the Catherine Bergego Scale (

6) and the Behavioral Inattention Test (

7). Frontal-executive function was assessed with the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) (

8), the Trail-Making Test, Part A (TMT-A) and Part B (TMT-B) (

9), and the Behavioral Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome (BADS) (

10). The results of the digit span and spatial span tasks, as well as those of the TMT-A, TMT-B, and FAB, were expressed as z scores adjusted for age, in accordance with a previously described method (

11). These results are summarized in

Table 1. The patient’s general cognition and attention were normal, and he showed no hemispatial neglect. However, his z scores on the FAB, TMT-A, and TMT-B were −4.1, 5.6, and 13.0 respectively, and he had a score of 69/129 on the BADS (scores of 19–69 indicate impairment). These scores were indicative of abnormalities in frontal-executive function. His episodic memory did not appear to be impaired, because he was able to recall three items from the MMSE. In addition, he could remember the faces, names, and hometowns of all of the therapists with whom he had worked. Finally, he was able to give accurate oral descriptions of the contents of his previous day’s training.

The patient’s persecutory delusions, delusional jealousy, and depersonalized comments continued daily for more than 1 month but gradually decreased. After 4 months, his complaints of delusions and depersonalizations ceased. He showed great improvement in frontal-executive function, as indicated by the results of neuropsychological tests (z scores on the FAB, TMT-A, and TMT-B: z=1.1, z=0.4, z=4.1, respectively; BADS score, 114/129).

Discussion

Our patient experienced delusions without hallucinations resulting from a midbrain infarction. Peduncular hallucinosis is a mental symptom that is known to occur after damage to the midbrain or pons (

12). However, instead of delusions, complex visual or tactile hallucinations occur. Generally, the patient is aware of the hallucinations and often has a sleep

-wake rhythm disorder. In contrast with peduncular hallucinosis, our patient did not present with hallucinations. Other reports have described cases in which a lesion in the midbrain or pons led to hallucinations and delusions without awareness (

1–

3). However, there are no reports, to our knowledge, of a patient presenting only with delusions in the absence of hallucinations following damage to these sites, thus making the patient in the above case unique. In reports of localized damage, noradrenergic neuron abnormalities were hypothesized to have caused psychosis in a patient who had surgery on the mesencephalic tegmentum (

1), whereas dopaminergic neuron abnormalities were assumed to be the cause of a case of psychosis following substantia nigra infarction (

2). Nishio et al. (

2) reported a case in which various frontal lobe symptoms, hallucinations, and delusions developed after infarction of the substantia nigra, and single-photon emission computerized tomography revealed decreased circulation in the frontal lobe. The authors assumed that disruption of ascending dopaminergic projections to the frontal-subcortical circuits was the cause of the altered mental symptoms.

Right-hemisphere brain damage is commonly reported in cases of delusions after stroke (

13). In a systematic review of poststroke psychosis, lesions typically occurred in the right hemisphere, and the most common psychosis was delusional disorder (

14). These findings suggest that right-hemisphere lesions, or networks with key nodes in the right hemisphere, may play a role in the development of delusions. Devinsky (

15) suggested that delusions arise when the unchecked left hemisphere unleashes a “creative narrator” from the monitoring of self, memory, and reality—functions typically performed by the frontal- and right-hemisphere areas. Coltheart (

16) similarly proposed that one of the factors in the development of delusions is a defective “belief evaluation system,” localized in the right frontal cortex. In our patient, MRI revealed lesions that involved the right substantia nigra. Notably, the substantia nigra is directly connected with the frontal cortex (

17) and has dopaminergic projections to frontal-subcortical circuits that modulate frontal lobe functions. Disturbances of these direct or indirect pathways to the right frontal lobe may be essential in the development of a patient’s delusions. This hypothesis is supported by our observation of abnormalities revealed by frontal executive function tests when our patient exhibited delusional beliefs, and his improvement of delusional symptoms was coincident with normalization of frontal executive function.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that right midbrain infarctions should be regarded as a potential cause for the sudden occurrence of delusions without hallucinations in elderly individuals.