Mania can be from primary etiology, as seen in bipolar disorder, or resulting from secondary causes. In DSM-5, secondary bipolar disorder is characterized as disturbances generally caused by another medical condition or induced by a substance or medication. These disturbances cause the same symptoms as primary mania, including a prominent and persistent period of abnormally elevated, expansive, or irritable mood and an abnormally increased activity or energy. In addition, secondary mania must be supported by evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings to suggest the direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition or exposure to a medication (

1). Common medical causes include neurological conditions, such as tumors, frontotemporal dementia, stroke, and traumatic brain injury (TBI), whereas medications and substance causes can include corticosteroids and stimulants (

2). Secondary mania often develops within a short period (hours to days) after the physiological insult and may occur throughout the lifespan. The prevalence of secondary mania is variable due to its multitude of potentiating factors. In a retrospective chart review of 755 patients evaluated by the psychiatry consultation service in a general hospital, it was found that in a 1-year period, 13 of 15 (87%) patients diagnosed with mania met criteria for secondary mania (

3). Here, we discuss a case of a man in his late 60s who developed mania after diagnosis and treatment of his primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL), in which the cause of the mania was likely multifactorial.

CASE REPORT

A man in his late 60s, with no prior psychiatric or substance use diagnoses or hospitalizations, was brought to psychiatric attention following chemotherapy for treatment of PCNSL. Pertinent past medical history included coronary artery disease managed with aspirin.

The patient’s initial presentation to his primary care physician in March occurred after having a decrease in mood as a result of significant physical limitations after falling off a ladder. Over the course of the next 6 weeks, his mental status further deteriorated. He endorsed symptoms of “brain fog” characterized by difficulty with cognitive functioning and higher-level processing. He felt increasingly fatigued and tired and was sleeping up to 22 hours a day. His wife described that his presentation was different from his baseline (normally outgoing and expressive). Blood work demonstrated the patient’s complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B

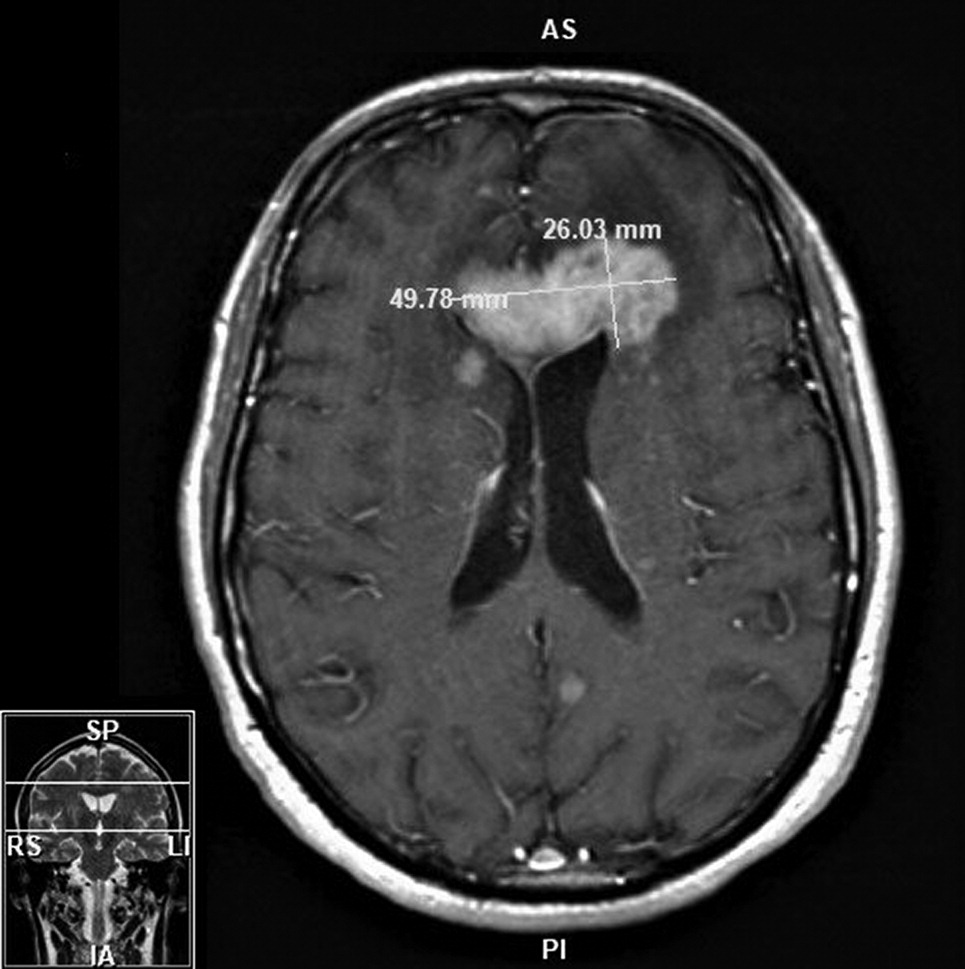

12 and thiamin levels, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein inflammatory markers to be within normal limits, as well as negative hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV results. Head imaging in May (computerized tomography [CT] and MRI) revealed two intracranial masses involving the right basal ganglia and left frontal lobe with mild vasogenic edema and mass effect (

Figure 1). The patient was referred to a nearby tertiary care hospital, where a stereotactic CT-guided biopsy indicated an aggressive, myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88) positive, B-cell lymphoma. Further imaging on positron emission tomography CT (PET-CT) showed PCNSL without extracranial involvement. Bone marrow biopsy was negative for lymphoma.

The patient was started on high-dose methotrexate (HDM; 8.3–10.8 g), rituximab, and temozolomide (MRT) induction therapy. He completed a total of nine cycles over 4 months starting in June. Regular blood monitoring revealed persistently high serum concentration of methotrexate (>0.10 mcmol/L). Over this time, he received 8-mg intravenous dexamethasone every other week (for a total of 10 doses) for vasogenic edema secondary to tumor mass effect. In addition, five scattered doses of baclofen (10 mg) were given for hiccups. A surveillance brain MRI after the first two cycles of MRT showed resolution of enhancement and decrease in multiple areas of the abnormal T

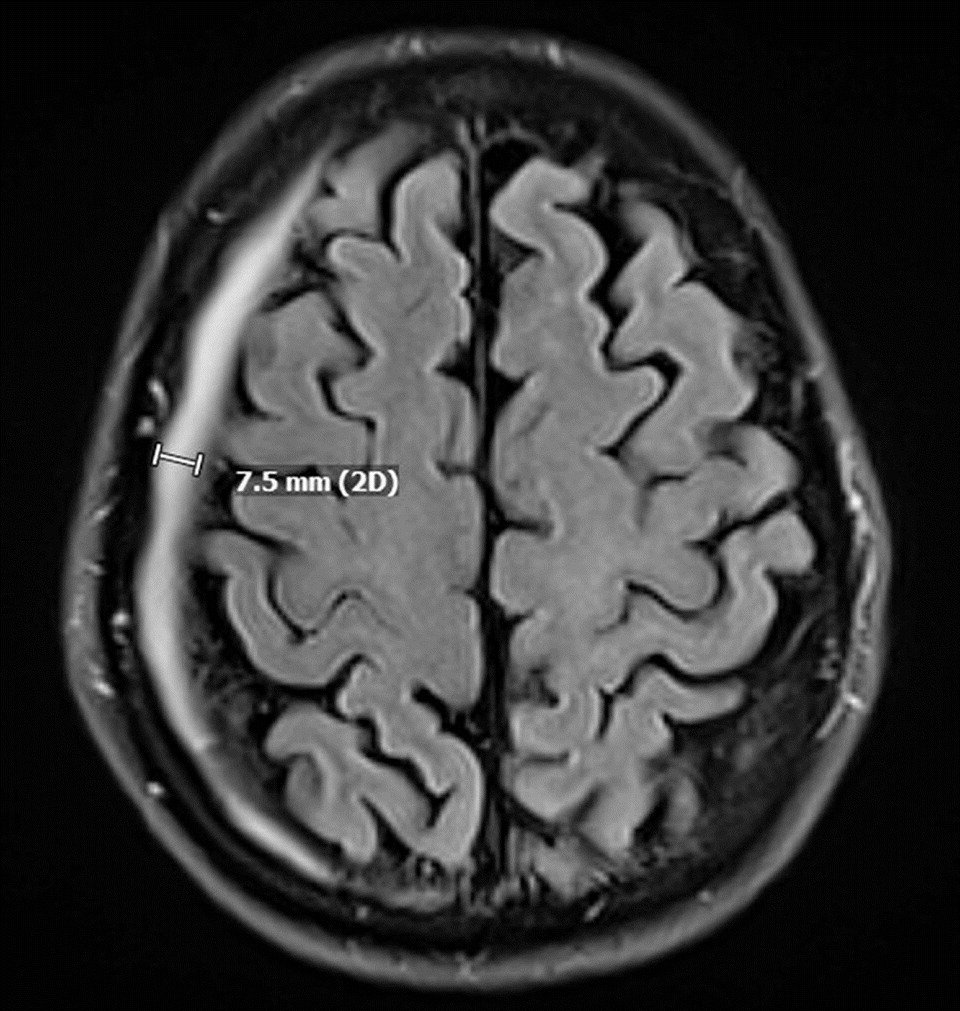

2 signal. Follow-up imaging in August noted regression of the tumor size, as well as an incidental, asymptomatic right-sided 7-mm chronic subdural hematoma (SDH) with no noted mass effect or midline shift (

Figure 2).

In September, a repeat MRI showed resolution of the patient’s PCNSL, and he was determined to have achieved complete remission. A repeat PET-CT for tumor restaging—part of the process for his evaluation prior to bone marrow transplant—was negative for extracranial PCNSL. However, there was an interval increase in the size of the SDH on brain MRI, which resulted in temporary postponement of the patient’s stem cell transplant (SCT) so that the hematoma could resolve. Findings from laboratory studies conducted as part of his pre-SCT evaluation (coagulation studies, vitamin D, iron panel, and urinalysis) were all within normal limits. His infectious disease panel was nonreactive for cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B core antibodies, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B virus nucleic acid testing, hepatitis B virus antibodies, hepatitis C virus nucleic acid testing, HIV-1/-2, HIV-1 nucleic acid testing, human T-lymphotropic virus -I/-II, syphilis antibodies, Trypanosoma cruzi antibody, and West Nile virus nucleic acid testing. Chromosome analysis showed normal karyotype of 46, XY.

In early October, the patient’s wife expressed concern that he was exhibiting impulsive behavior, disinhibition, irritability, and mood changes. A repeat head CT showed stable but slightly increased size of the SDH, with minimally associated mass effect. Blood work was noncontributory for CBC, CMP, lipids, and thyroid panel. Over the course of the month, the patient’s condition progressively worsened, and he developed new daily symptoms of inflated self-esteem, irritability, lability, and elevated mood. According to his wife, he also had a decreased need for sleep and demonstrated pressured speech. In addition, he became easily distracted and disorganized to the extent that he was unable to complete his usual tasks as a teacher. He was also noted to have increased goal-directed activities, such as hypersexuality and hyperreligiosity, as well as irresponsible behaviors, such as nondiscretionary spending.

Despite these documented behavioral changes, no focal neurological deficits or organ-specific symptoms were found. He was evaluated by neurology and neurosurgery teams, who described him as “disorganized, grandiose, and loquacious” (quoted from the patient’s chart). He was noted to be careless when performing the clock-drawing portion of the cognitive examination. His changes in behavior raised concerns for PCNSL recurrence, with frontal lobe involvement. A repeat brain MRI showed a slight decrease in the size of the SDH, with no indication of PCNSL recurrence. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed no concerns regarding an infectious or autoimmune etiology to his presentation.

The patient was referred for a psychiatric evaluation in late October, where it was concluded that he was having a manic episode. His Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was 31/60, and his Patient Health Questionnaire–9 score was 0/27. He was subsequently admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Over the course of 10 days, the patient was stabilized on valproic acid (500 mg b.i.d.) and olanzapine (5 mg qAM and 10 mg q.h.s.). His YMRS score on discharge was 15, with sufficient functional improvement of his manic symptoms to warrant an outpatient level of care. Just under 3 weeks after hospital discharge (late November), his YMRS score was 0; in mid-December, he was able to successfully undergo an autologous SCT. Over the next 3–4 months, he underwent a slow and gradual titration off his psychotropic medications with no recurrence of his manic symptoms.