Apathy and Huntington’s Disease: A Literature Review Based on PRISMA

Abstract

Objective:

Methods:

Results:

Conclusions:

Current Definitions of Apathy

| Robert et al. (27) | Mulin et al. (23); Robert et al. (24) |

|---|---|

| Criterion A: Quantitative reduction in goal-directed activity in behavioral, cognitive, emotional, or social areas, compared with the patient’s previous levels of functioning. These changes may be reported by the patients themselves or observed by others. | Criterion A: Reduction in motivation compared with the patient’s previous level of functioning |

| Criterion B | Criterion B: Two of the three following domains of apathy, which must have been present for at least 4 weeks. |

| Subcriterion B1: Behavior and cognition | |

| Loss of or diminished, goal-directed behavior or cognitive activity, as evidenced by at least one of the following: | |

| General level of activity | Subcriterion B1: Loss of or diminished goal-directed behavior |

| Persistence of activity | Subcriterion B2: Loss of or diminished goal-directed cognitive activity |

| Making choices | Subcriterion B3: Loss of or diminished emotions |

| Interest in external issues | |

| Personal well-being | |

| Subcriterion B2: Emotion: loss of, or diminished, emotion, as evidenced by at least one the following: | |

| Spontaneous emotions | |

| Emotional reactions to environment | |

| Impact on others | |

| Empathy | |

| Verbal or physical expressions | |

| Subcriterion B3: Social Interactions: Loss of, or diminished engagement in social interaction, as evidenced by at least one of the following: | |

| Spontaneous social initiative | |

| Environmentally stimulated social interaction | |

| Relationship with family | |

| Verbal interaction | |

| Homebound | |

| Criterion C: These symptoms (A and B) cause clinically significant impairment in personal, social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. | Criterion C: Symptoms should cause clinically significant impairment in various functional domains. |

| Criterion D: The symptoms (A and B) are not exclusively explained or due to physical disabilities (e.g., blindness and loss of hearing), motor disabilities, a diminished level of consciousness, the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., drug of abuse, medication), or major changes in the patient’s environment. | Criterion D: Exclusion criteria specify symptoms that mimic apathy, such as the direct physiological effects of a substance |

Apathy Assessment Scales

| Apathy assessment tool | Characteristic |

|---|---|

| Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS) | This rating scale covers four dimensions of HD: motor, cognitive, functional, and behavioral. The latter comprises 10 items, only one of which refers to apathy (“inability to enjoy anything”). This apathy item is included in the general mood category. |

| Problem Behaviors Assessment for Huntington’s Disease (PBA-HD) | This semistructured interview features 40 items that cover a range of psychological symptoms, including apathy. It is widely used in studies of HD. It measures the frequency and severity of apathy over the previous 4 weeks (scores between 0 and 5). There is a short version of the PBA. |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory | This is based on an interview with a caregiver. The apathy subscale consists of a yes/no screening question followed by seven subquestions, depending on the answer to the first question. It covers loss of interest, lack of motivation, decreased spontaneity and enthusiasm, loss of emotion, flat affect, and disinterest in carrying out new activities. |

| Structured Clinical Interview for Apathy | This interview was designed to detect apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. It covers “lack of motivation relative to the individual’s previous level of functioning, lack of effort to perform everyday activities, lack of interest in learning new things or in new experiences, lack of self-concern, flat affect and lack of emotional response.” It was used, together with AES and UHDRS, as a measure in the first treatment trial for apathy in HD. |

| Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) | The AES was the very first apathy scale (18 items). It is now available in three versions: caregiver (AES-I), clinician (AES-C), and self-report (AES-S). It covers the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of apathy. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale. A high score indicates severe apathy. |

| 14-Item Apathy Scale | This simplified version of the AES covers the three dimensions of apathy identified by Marin (26). The psychometric properties of this tool have not been fully investigated. |

| Frontal Systems Behavior Scale | This scale is designed to evaluate disorders after frontal lesions: apathy (14 items), disinhibition (15 items), and executive dysfunction (17 items). There are self, informant, and clinician versions. The apathy subscale covers loss of interest and self-care, and difficulties in initiation and spontaneity. |

Apathy and Other Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Apathy and Huntington’s Disease

| Study | Sample size | Disease stage | Neuropsychiatric measures | Major findings related to apathy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Craufurd et al. (48) | 134 | Confirmed HD | PBA-HD for apathy, anxiety, depression, and irritability, etc. | Presence of three factors—apathy, irritability, and depression—were found. Apathy was the only factor related to disease duration. |

| Paulsen et al. (49) | 52 | Confirmed HD | NPI for apathy, anxiety, agitation, dysphoria, irritability, and anxiety, etc. | Prevalence of apathy was 55.8%. Apathy prevalence increased with disease duration in HD. Apathy was linked to disruption of the medial prefrontal circuit. |

| Thompson et al. (50) | 82 | Confirmed HD | PBA-HD for apathy, depression, and irritability | Apathy was correlated with cognition and motor functions. The apathy subscale was a valid measure of apathy severity in HD. The correlation between apathy score and cognitive impairment in HD was explained by disruption of striatofrontal circuits. |

| Baudic et al. (51) | 36 | Early HD | Semistructured interview with patient and close relative (presence and severity of apathy); MADRS for depression | Twenty out of 36 patients were apathetic. Apathy was associated with cognitive impairment in early HD: attention, executive functions, and episodic memory. In apathetic patients, cognitive impairments were linked to motor disturbance. |

| van Duijn et al. (52) | 152 | HD mutation carriers | AS for apathy | Apathy had a prevalence of 32% in mutation carriers (0% in noncarriers). |

| 56 | Noncarriers | CIDI for depression | Apathy was associated with depression, poorer overall functioning, motor and cognitive symptoms, and increased use of psychotropic medication. | |

| Naarding et al. (53) | 34 | Confirmed HD | AES for apathy | Prevalence of apathy was 52%. Apathy was far more present in HD than depression, and these two entities were largely distinct dimensions. Apathy was related to cognitive impairments and functional decline. |

| Duff et al. (54) | 745 | Expansion positive (premanifest) | FrSBe for apathy, disinhibition, and executive functions | Pre-HD expansion positive patients had significantly higher total FrSBe scores than participants with negative expansion. |

| 163 | Expansion negative | |||

| Reedeker et al. (55) | 122 | Premotor and motor HD | AS for apathy and CIDI for depression | At baseline, 34 out of 122 patients exhibited apathy. Apathy was correlated with lower clinical and neuropsychiatric scores. Thirteen (14%) of 88 patients without apathy at baseline developed apathy by the 2-year follow-up. Apathy was reversible: 14 (41%) of 34 patients who had apathy at baseline no longer manifested apathy 2 years later, while 20 (59%) patients remained apathetic. Cognitive dysfunctions contributed to apathy onset in HD. |

| Thompson et al. (56) | 111 | Confirmed HD; stages I–II; stages II–III; and stages III–IV | PBA-HD for apathy, depression, and irritability | Prevalence of apathy was 68% at stages I–II, 73% at stages II–III, and 85% at stages III–IV. Apathy scores were associated with HD progression; apathy was intrinsic to disease progression. Apathy, depression, and irritability were each associated with a distinct longitudinal profile, suggesting that each had a different neurobiological substrate. |

| Tabrizi et al. (57) | N=366 at baseline; N=298 at 36-month follow-up | Pre- and early HD | PBA for apathy | Apathy scores increased with disease progression. |

| van Duijn et al. (58) | 1,993 | Premanifest and manifest HD | UHDRS-b for depression, apathy, psychosis, irritability/aggression, and obsessive-compulsive behaviors | Prevalence of apathy was 47.4% (19.3% mild apathy and 28.1% moderate to severe apathy). Apathy was the main symptom, occurring most often in advanced HD. Apathy was perhaps the only nonmotor feature that was linearly associated with the neurodegenerative progression. |

| Mason and Barker (59) | N=108 at baseline; N=73 at 18.7 months follow-up | Premanifest and advanced HD | AES-P (participant version) for apathy AES-I (companion version for caregivers) for apathy | Prevalence of apathy was 26.9% (N=29/108) of patients were apathetic according to self-rated AES scores, and 37.9% (N=30/79) of patients were apathetic according to AES (companion version) scores. Statistically, apathy could be equally assessed by either patients or their proxies. Apathy did not progress during an 18-month follow-up, and it was distinct from depression. |

| Martinèz-Horta et al. (60) | 230 | Premanifest far from motor-based HD onset (pre-HD, criterion A); premanifest patients close to motor-based HD onset (pre-HD, criterion B); and early manifest HD | PBA-s for apathy, depression, irritability, psychosis, and dysexecutive behavior | Prevalence of apathy was 23% in pre-HD criterion A, 64% in pre-HD criterion B, and 63% in early HD. Apathy could occur up to 10 years before disease onset. Apathy was closely linked to the neurodegenerative process of HD. |

| Kempnich et al. (61) | 32 | Premanifest and manifest HD | TASIT for emotion recognition and FrSBe for apathy and disinhibition | Emotion recognition skills were associated with apathy measures. This association was independent of disease severity (motor dysfunction). Emotion recognition and apathy had an overlapping neural circuit (anterior cingulate circuit). |

| Sousa et al. (7) | 29 | Confirmed HD | AES-C for apathy and BDI-II for depression | Apathetic patients displayed more cognitive disorders than nonapathetic patients. Apathy was strongly related to motor symptoms, disease duration, and the presence of cognitive disorders. |

| Fritz et al. (14) | 487 | N=193 pre-HD; N=186 early HD; N=108 late-stage HD | PBA-s HD for 11 items; one of which was apathy | Apathy could appear up to 3 years before disease onset and increased as the disease progressed. Apathy was correlated with disease duration and motor and cognitive disorders, strongly linked to invalidity, and had a negative impact on quality of life. |

| Jacobs et al. (15) | 220 | Pre- and manifest HD; N=114 employed; N=106 unemployed | PBA-s HD for apathy, depression, and irritability | Apathy was the main predictive factor (in association with executive functions) for unemployment and had a negative impact on quality of life. |

| Baake et al. (62) | 31 | Premotor manifest | AES for apathy | Apathy severity increased with disease progression. Premotor manifest patients experienced a higher level of apathy that went unnoticed by their caregivers. |

| 49 | HD, | |||

| Early motor manifest | ||||

| 29 | HD | |||

| Late motor manifest | ||||

| HD | ||||

| Baake et al. (63) | 91 | Premotor manifest | PBA-s for 11 items; one of which was apathy | Prevalence at baseline was 12% for pre-HD, 24% for stage 1, and 50% for stage 2 of motor manifestations. The percentage of apathetic participants increased over 2 years. Apathy was present in the early stages of HD and was associated with thalamic atrophy in HD gene carriers. Apathy had an underlying neural mechanism. |

| 80 | Motor manifest | |||

| Aldaz et al. (64) | 53 | Mild, moderate, and severe stages of HD | PD NMS Quest covering nine domains (apathy, depression, and digestion, etc.) | Prevalence of apathy was 64%. Up to 60% of patients in slight-mild stages complained of apathy, and therefore apathy can appear early in the disease course. |

| Misiura et al. (65) | 797 | Prodromal HD | FrSBe for apathy and depression | Greater severity of apathy was associated with striatal atrophy, and increased apathy was related to reduced cognitive functions. |

| McLauchlan et al. (66) | 51 | Pre-HD to moderate HD | AES for apathy and PBA-s for the 11 symptomsb and BIS-BAS for reward value, reward effort, and response to reward and loss | Apathy was related to a deficit in response to loss. Altered response to reward or altered reward effort valuation was not necessary to develop apathetic behavior. |

| De Paepe et al. (67) | 46 | N=22 pre-HD; N=24 manifest HD | LARS-s for apathy and PBA-s for apathy and affective components (depressed mood, suicidal ideations, and anxiety) | Manifest patients displayed higher levels of overall apathy and auto-activation deficit. Pre-HD patients only had higher levels of auto-activation deficit. Increased apathy was correlated with HD progression. |

| Gunn et al. (68) | 7,914 | N=974 FM; N=1,041 GN; N=1,790 pre-HD; and N=4,109 manifest HD | PBA-s for apathy, affect, and irritability | Patients with HD underestimated their apathetic symptoms. Informants made major contributions to apathy assessments. |

| Andrews et al. (69) | 229 | N=118 pre-HD; and N=111 early HD | PBA-s HD for apathy BDI-II for depression | In premanifest HD, severe apathy symptoms predicted a more rapid cognitive decline. By contrast, in early manifest HD, motor signs were better predictors of cognitive decline than apathy. |

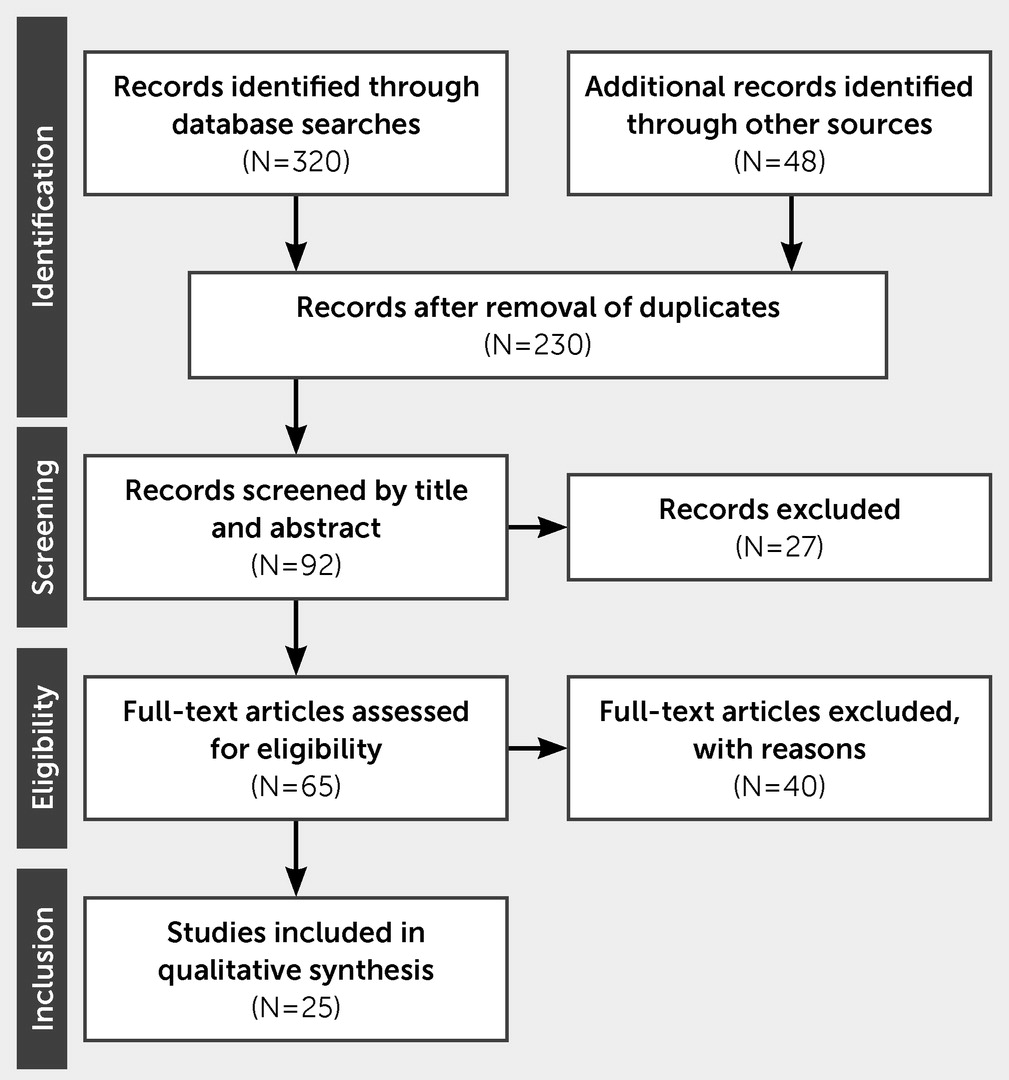

Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Data Extraction

Quality Appraisal

Results

Limitations of the Current Concept of Apathy

Conclusions

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Keywords

Authors

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).