In refining the models, categories are in place. Dimensions remain exploratory. Some dimensional measures appear in DSM5 (

8), but are relegated to a section on “Emerging Measures and Models,” separate from the main section on diagnoses (

2,

8). In ICD11, dimensions are also proposed (

9), but as in the DSM, categories remain central.

Outside DSM and ICD, alternative dimensional models have been suggested (e.g., HiTOP, see Krueger et al. 2018 (

10)). In research, neurobiological domains (e.g., RDoC (

11)) have been explored as possibly more strongly associated with underlying mechanisms than diagnostic categories. Various clusters of symptoms exist both as freestanding and co‐morbid conditions (

12), and these clusters may be key structural elements of illness. Similarly, some symptoms, such as paranoia or suicidality, appear across disorders and are worth exploring as individual items, separate from diagnosis (

13).

Ultimately, progress in applying dimensional features depends on finding the right dimensions (

4,

9). They must accurately characterize illnesses, contribute information beyond categorical diagnoses, and be practical to implement. Previously, we reviewed the evidence on categorical and dimensional classifications of psychoses (

4). Past studies were relatively consistent in observing similar dimensional features in patients with psychoses. Among 41 studies, four or five factors were common, often including positive, negative, and affective symptoms. Only two studies, of modest size, compared the relative fit of categories and dimensions, both derived from their own sample (

14,

15). No studies compared categories and dimensions derived from the same sample to one another, to standard diagnoses and to any external validator. The current study does and its results provide guidance on modifications of diagnostic systems and the design of future investigations on the architecture of psychoses.

Discussion

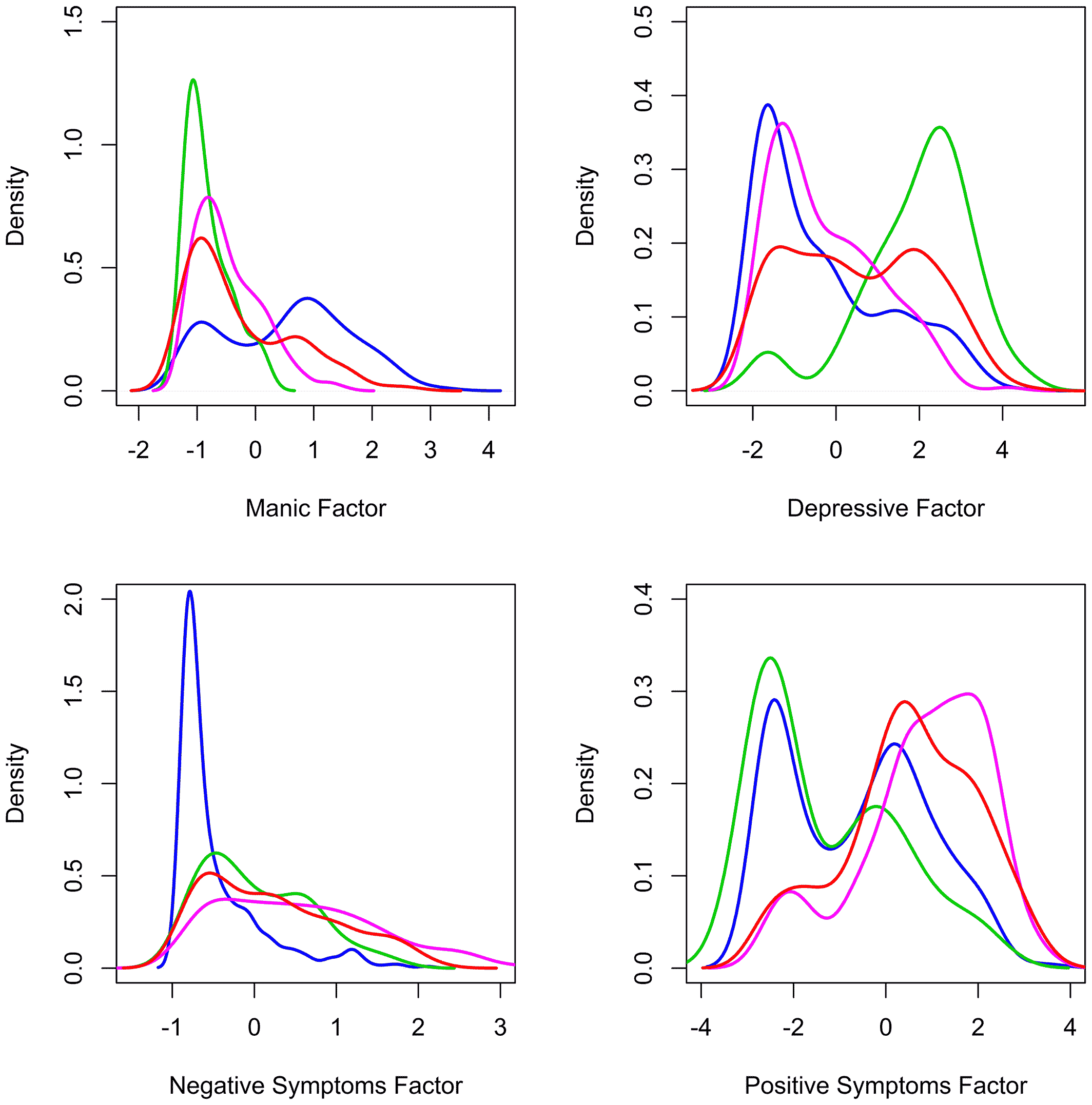

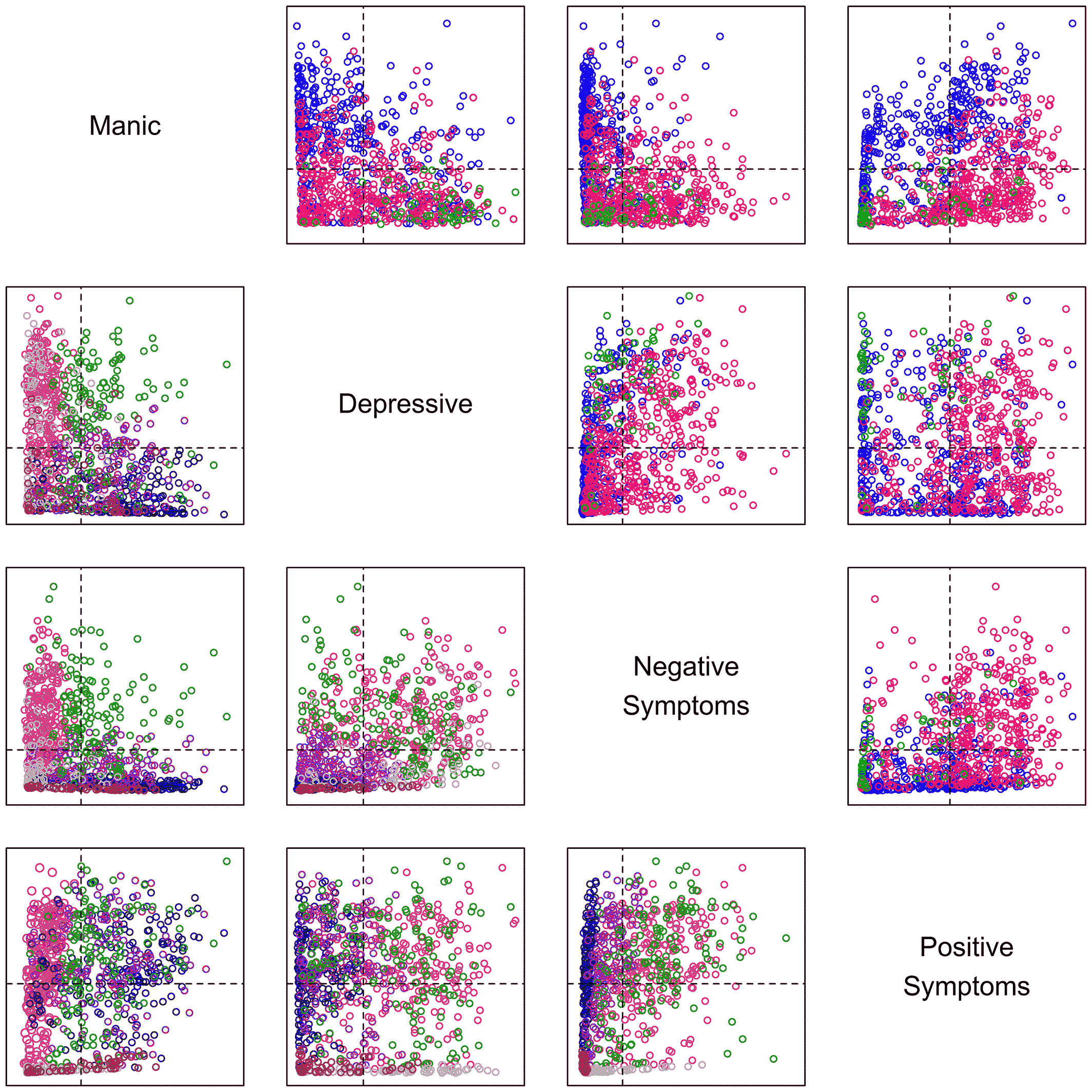

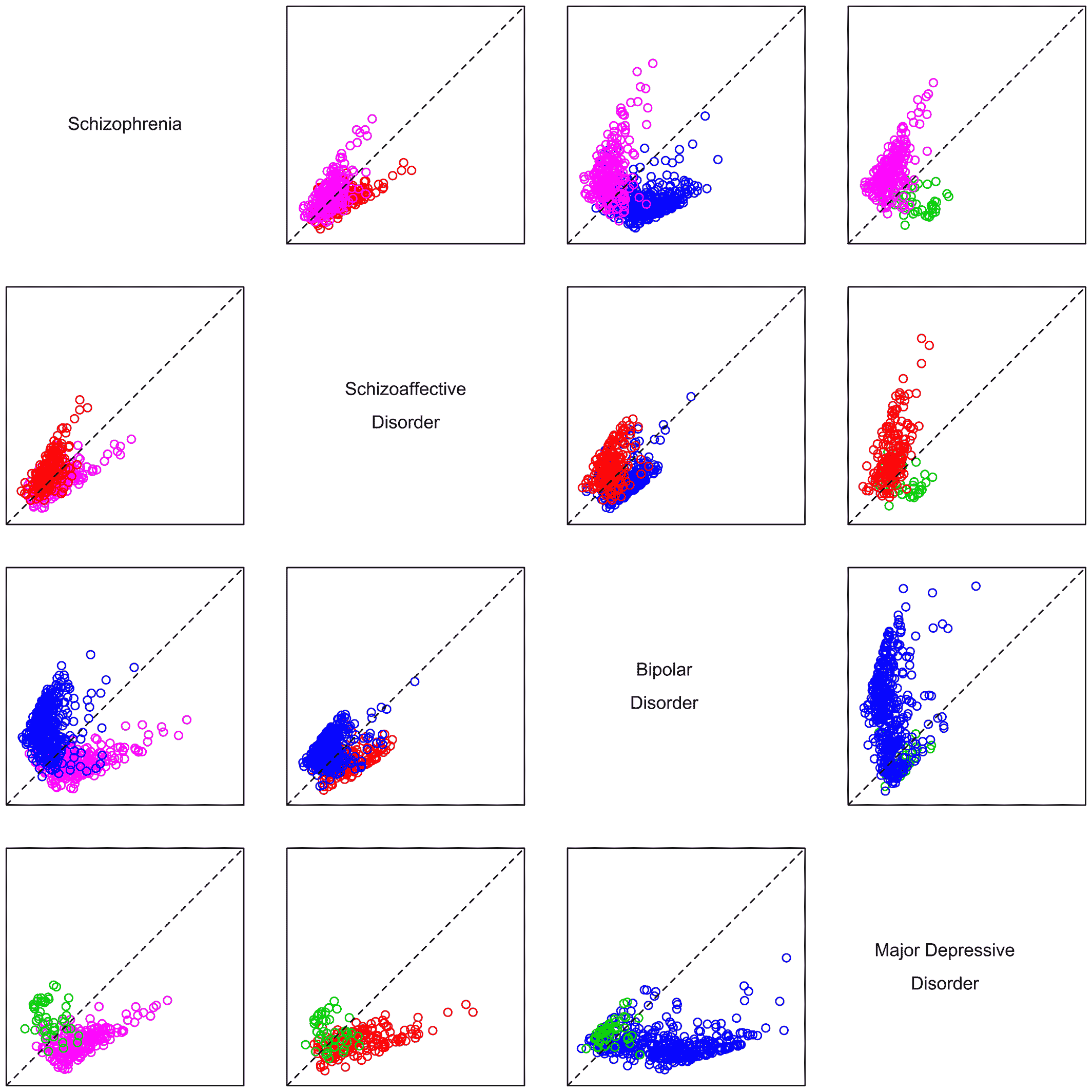

The results of these analyses of clinical presentation confirm factors as valuable descriptive features of psychoses. The factors observed are robust, having been repeatedly documented as key features in this and past studies. And they better characterize patients in this data set than traditional (DSM) categories or alternative categories derived from the very patients studied. The patients' clinical presentations are well described by the identified factors. By comparison, clinical characteristics do not reliably suggest categories of patients. Rather, individual patients are spread throughout the multidimensional space described by the factors, suggesting their illnesses do not fall into clusters with clear divisions.

The existing literature has highlighted roles for both categorical and dimensional features in nosology of psychoses. Ours is the first study, to our knowledge, comparing categories and factors derived from the same patient population with one another and with standard diagnoses, as well as the only such study with an external validator. We derived the same factors observed in other samples, suggesting that the findings are generalizable to a broader population of patients with psychoses. And as noted, they strongly suggest that using factors improves characterization of clinical presentation over DSM‐defined categories or data‐derived categories alone. While there is no gold standard for defining the structure of the psychoses, effective treatment, as determined by the responsible physician, likely reflects important aspects of illness. Thus, the correlation of factors with treatment is compelling evidence supporting the value of describing patients by factors in addition to categories.

The underlying architecture of the psychoses is complex. Thousands of genes and various external stressors work through numerous processes to determine clinical presentation (

13). Although clinical episodes vary in type and degree of symptoms, they have typically been modeled with a small number of categories, notably schizophrenia‐like or affective‐like psychoses, but with a telling intermediate category of schizoaffective disorders, suggesting either a continuum, co‐morbid illnesses, or a multidimensional structure of psychoses. The three‐category model has never satisfied the field as accounting for the diffuse range of patient presentations (

30). Many causes, including gene variants, and numerous higher‐level mechanisms, including circuit anomalies, are shared across diagnostic categories (

31,

32,

33). Standard categories are not homogeneous with regard to these underlying mechanisms (

13,

31). Further, symptoms and mechanisms producing those symptoms, are likely not only shared across illnesses, but also with the rest of the population (

34,

35). Current diagnoses provide a useful way to dichotomize people into ill and well groups and categorize people by approximate type of illness for treatment and study, but the illnesses are not all or none; they are dimensional (

6). Features of illness vary in severity and dimensions can help model the psychoses. Among these dimensional features are the factors consistently observed among the many studies of the psychoses. These factors are naturally complementary to categorical structures in characterizing psychoses (

5). They address aspects of psychosis missing in categorical models and thought to be relevant to a full description of these disorders.

There are limitations to this study. While it presents comparisons not previously examined, and is an order of magnitude greater than past studies of categorical and dimensional models, it is not large enough to provide fine details on the important components of either the categories or factors derived. In addition, the items contributing to the analysis were all from well‐established and validated clinical scales supporting dimensional assessment. This helped to ensure inclusion of the most common clinical features of the disorders and to capture the range of symptom severity, but also may have favored those items fitting well into a dimensional framework and tending to reliably correlate with the clinical features the scales were designed to assess. We are not suggesting that the factors we studied are the only factors to be considered. Rather, they are prominent and relevant ones that we and others have evaluated and found to be useful.

Cognitive symptoms were underrepresented and mood symptoms overrepresented in our study relative to some past studies investigating the structure of psychoses. Inclusion of additional items assessing cognition may have resulted in the identification of a cognitive factor, particularly given that a cognitive dimension has been identified in a number of other studies (

4) and a thought disturbance factor was represented in an alternate, less robust factor solution in our study. We have not addressed anxiety and substance abuse as factors, in part because they are not specific features of psychoses and present across all of our patient groups. However, we realize that they matter and require future consideration (

16). Similarly, we did not analyze for suicidality, which is associated with all psychiatric disorders and has, to some degree, its own genetic and experiential determinants (

36,

37). The sample population was examined cross‐sectionally. We modeled current states of the patients, the ones in which they presented for treatment. Additional data of value would include the course of symptom and diagnostic variability. Such data might be available in clinics with large groups of longitudinally treated populations. Incorporation of information on history in the diagnostic process may have given DSM‐based categories an advantage over data‐derived categories in our analysis. Our patients required hospitalization, which means they represent a more severe cohort than those seen in a community sample. We did not include data from experimental technologies, such as brain imaging, genomics or cell biology, but did use a variety of comprehensive symptom scales to characterize clinical presentation. Biomarkers, as they develop, can add value in modeling psychoses.

Our statistical approaches have limitations. We would have preferred to compare fits of dimensional, categorical, and hybrid models based on individual symptom ratings rather than identify categories based on the results of dimensional modeling. Our data did not support fitting models of this complexity. Finite mixture modeling, used to identify our clusters, has the potential to identify spurious categories when the assumption of multivariate normality is violated (

38). More generally, this and other approaches to identifying latent categories do not prove the existence of categories but rather describe the categories identified under a chosen set of rules and assumptions. Despite limitations, we can note that categories identified in our patients were sensitive to approach and, therefore, may not provide an optimal system for describing patients.

Categorical classifications of psychiatric disorders, as used for over 100 years, have shown utility in clinical work and for investigation (

6). However, psychiatric disorders only partially fit any categorical diagnostic model (

39). Current diagnostic categories group people with different symptoms and different causes and mechanisms of illness together. Concurrently, they separate people with overlapping genomic risk factors or who share aspects of altered brain structure and function into different cohorts. Improving the accuracy and detail of patient description by adding dimensions could be worthwhile (

6,

10).

The current results identify key dimensional factors that can be of utility in the nosology of psychoses and provide validation on the importance of those factors, including their fit as an accurate model of psychoses. The factors are not complex to assess and could easily be used for clinical and research purposes, as a complement to categorical models. The factors identified and validated here may be associated with particular sets of genes, particular biomarkers, particular altered developmental pathways, or particular targets for treatment. The same may be true for other factors mentioned but not further evaluated in our study. There is already evidence of the value of such comparisons of genes (

40) and other biomarkers (

33,

41) to factors, not just to standard diagnoses, in research on psychoses. Treatment decisions already follow factors, as suggested by the analyses in this study and the results of previous studies (

42).

Ultimately, categorical and dimensional models are complementary. A combined model should be best, as suggested by the current analysis. Neither the dimensional characterization of psychotic disorders nor the particular dimensions suggested by our analysis are new; DSM and ICD 11 have introduced dimensional features in exploratory fashion for psychoses (

2,

9). Rather, our results support the inclusion of these dimensional features in more completely characterizing the disorders and serve as a reminder that even validated and informative categorical classification systems may benefit from incorporating dimensional information. More research on categorical and dimensional models, on hybrid models combining the two, in new onset and established illnesses, in both cross‐sectional and longitudinal studies, and for clinical and research purposes, should all prove worthwhile going forward. Specifically, measures of the presence and severity of the factors noted here should be added to the diagnostic model and tested to refine their practicality and utility.