Conflict and containment events on acute inpatient psychiatric wards are associated with a substantial range of negative outcomes. Conflict events include violence, verbal abuse, rule breaking, use of alcohol or illegal drugs, self-harm, medication refusal, and absconding by patients. Containment events include coerced medication, seclusion, and manual restraint. When such events occur, patient and staff safety is put at risk, staff burnout and absence increase, and treatment can be disrupted, which hinders recovery and extends the patient's stay (

1–

4). The annual financial cost of conflict events and containment events in staff time alone across England is estimated to be £72.5 million and £106 million, respectively (

5).

The primary purpose of this study was to explore these and other potential causes of conflict and containment events by using a novel mixed-methods approach that combined and matched longitudinal qualitative and quantitative data. We analyzed which factors (qualitative data) significantly preceded up- and downturns in conflict and containment rates (quantitative data) on a number of wards over time.

Results

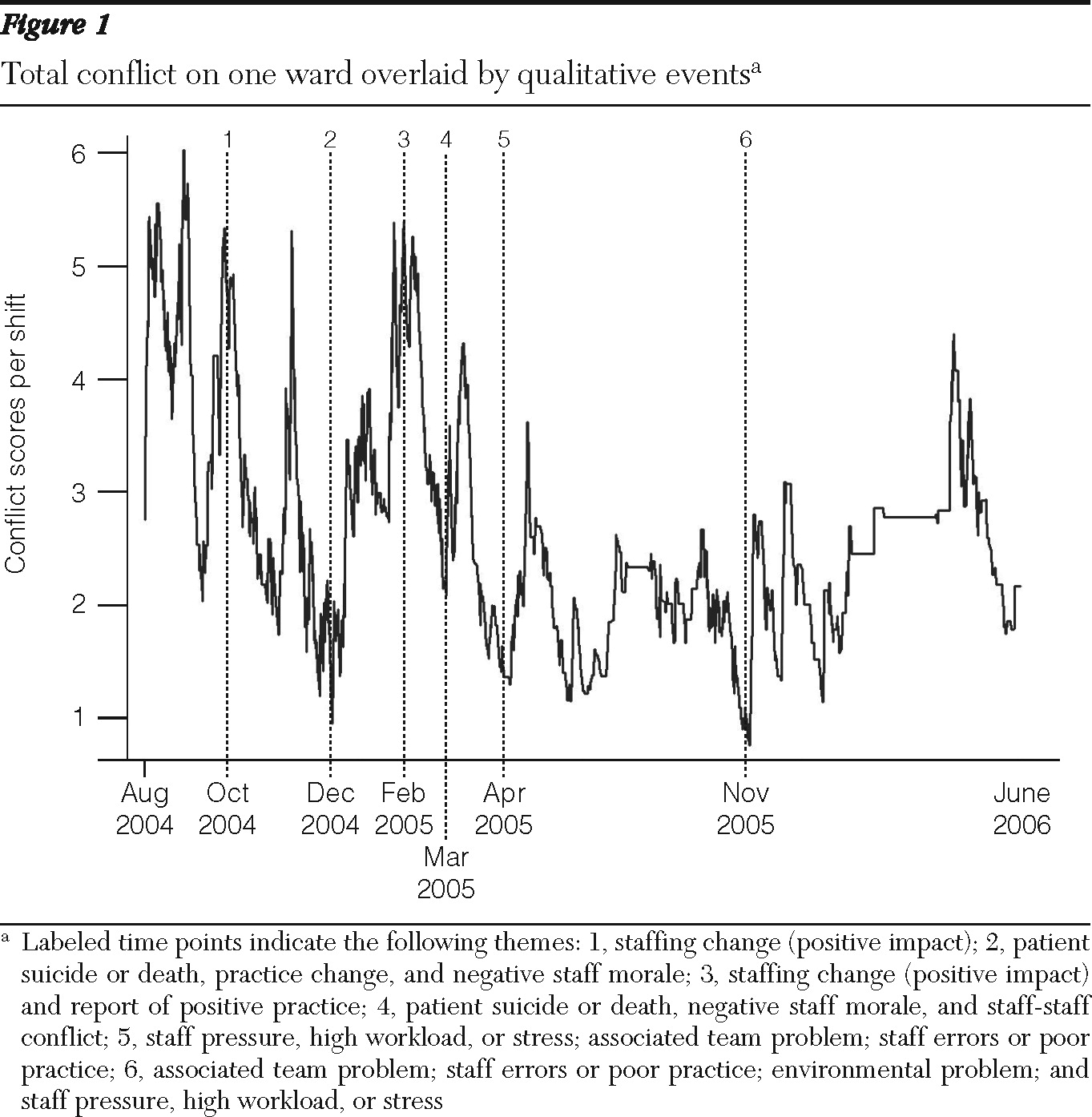

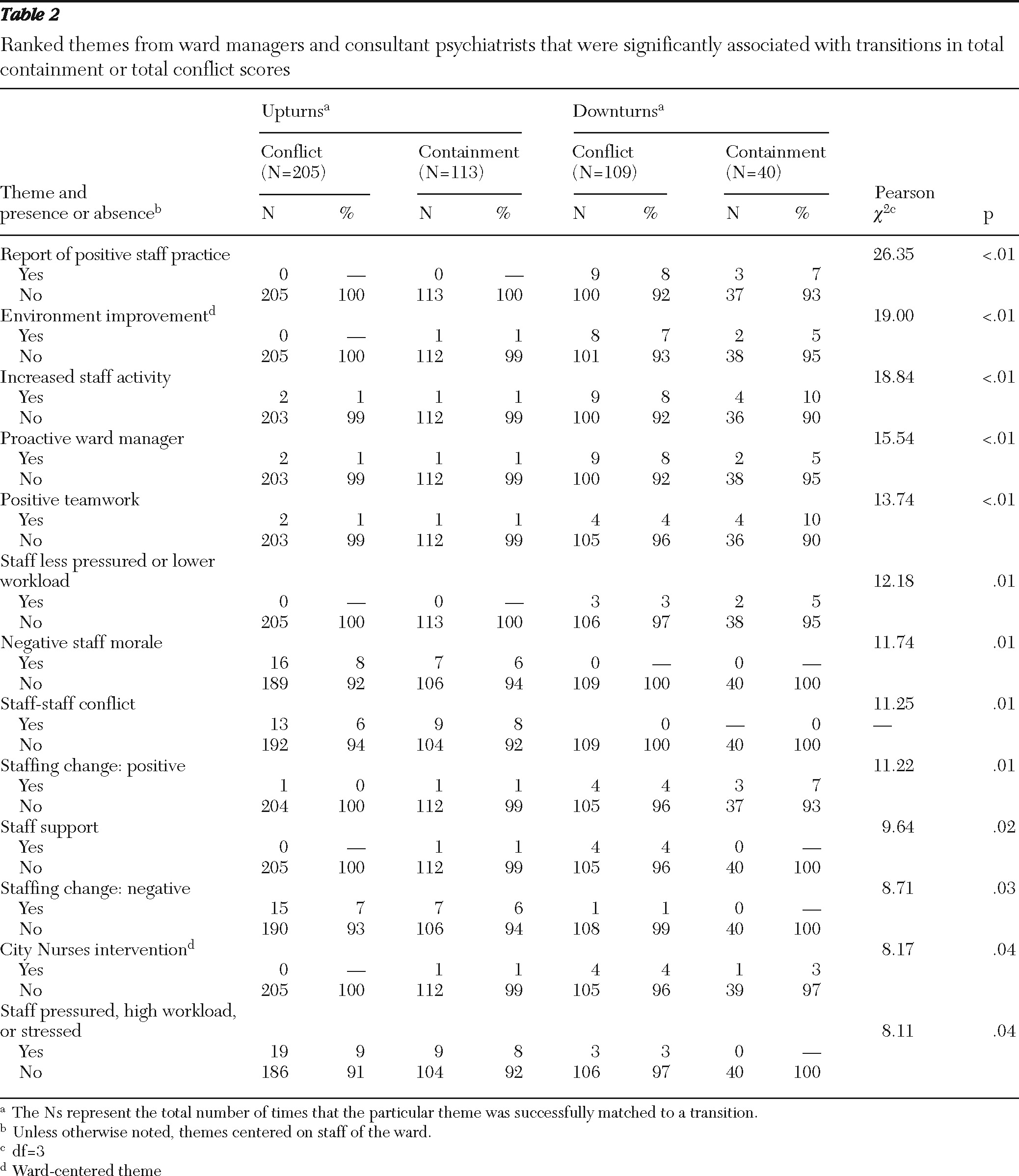

A total of 463 score transitions were identified. Of these, 128 were identified as upturns in total conflict scores and 112 were upturns in containment scores, 118 were downturns in conflict scores, and 105 were downturns in containment scores.

A total of 123 transitions (27%) were successfully matched with at least one event listed in the qualitative timeline documents. Many of the same events were matched to both conflict and containment transitions that occurred during the same time. Taking this into consideration, 323 events were matched to upturns and downturns in conflict and containment.

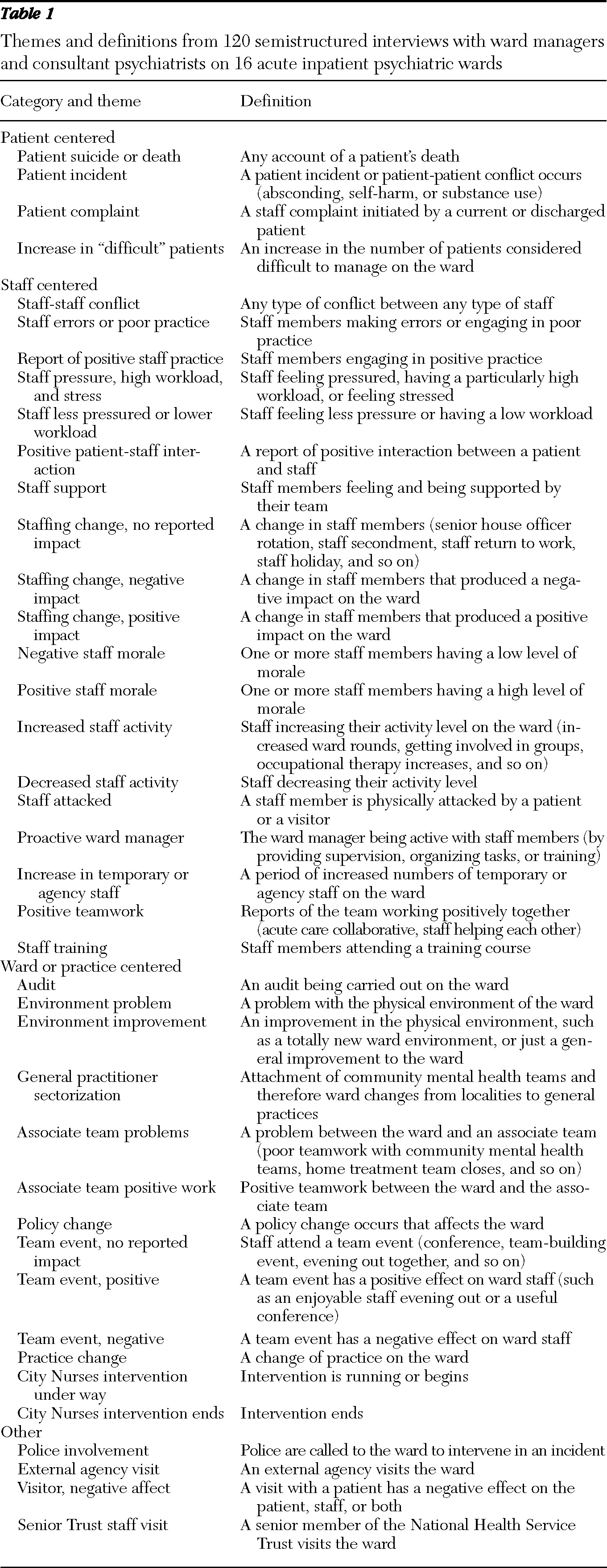

The thematic analysis of the matched events produced 40 themes (

Table 1), 13 of which were found to be significantly associated with upturns or downturns in conflict and containment rates (

Table 2). Eleven of these centered on the ward staff and two centered on the ward and its operation, but there were no consistent significant associations between upturns and downturns and patient-centered themes. Specifically, the themes significantly associated with upturns in score transitions were (in order of significance) negative staff morale, staff-staff conflict, staffing change resulting in a negative impact, and staff feeling pressured, having a high workload, or feeling stressed. Themes significantly associated with downturns in score transitions were (in order of significance) report of positive practice, environment improvement, increased staff activity, proactive ward manager, positive teamwork, staff feeling less pressured or having a lower workload, staffing change resulting in a positive impact, staff feeling or being supported, and a City Nurses intervention being under way.

Discussion

Each significant theme associated with the score transitions was in the expected direction: themes with negative implications preceded upturns in conflict and containment scores, whereas themes with positive implications preceded downturns in conflict and containment scores, suggesting a strong relationship between conflict and containment causes and rates. The only exception to this was staff support, which was significantly associated only with conflict downturns.

The staff-centered theme most strongly associated with score transitions was report of positive staff practice. This theme pertained to staff engagement in practice that produced a positive outcome. Examples of this involved a nurse who, after recently attending a course, ran relaxation groups that were well received by the patients or a staff member who “did well and helped save a dying patient in difficult circumstances.” The theme next most strongly associated with transitions was environment improvement. This item refers to improvements made to the ward's physical environment, either by making effective modifications to an existing ward or by moving patients to a different ward with a more therapeutic physical environment. There are several reports in the literature linking improvements in the ward environment to fewer adverse incidents, usually when a new unit is opened (

11–

15). However, such studies are often confounded by the many changes in policy and practice that are introduced along with such a move. This study's result is the first to show the impact of a naturalistic change in environments because of normal ward moves and refurbishments. The related theme of environment problem was reported too infrequently for assessment of impact.

The item of increased staff activity was also highly significantly associated with preceding score transitions. This referred to occasions when staff increased their level of activity in the ward, such as getting more involved in various groups, spending more time with patients, and, in general, more frequently using their work time productively. A specific example of this was when staff began organizing more patient activities across the week, including taking patients on day trips. A more general example was “nurses are now being much more proactive and assertive with patients.” The amount of attention patients receive from staff has been shown to predict better outcomes (

16), although this was the first study to document the causality between increased staff activity and better outcomes. It is also likely that simply being seen to be active would be viewed favorably by staff and patients. Furthermore, feeling useful may also increase staff self-efficacy, a sense of personal accomplishment, and morale.

Having a proactive ward manager was also strongly associated with score transitions. Such events included ward managers' providing regular supervision, organizing and allocating work tasks, and sending their staff and themselves to training courses. This theme was likely to augment staff activity levels in that a proactive ward manager encourages and supports staff in spending their time productively. The proactive ward manager will also be a positive role model for the ward staff and will in general be viewed favorably. Previous research has not supported a direct link between leadership and outcomes within psychiatric settings (

17,

18). However, it has been shown to predict positive teamwork (

19), a theme that was also found to be strongly associated with score transitions in this study. Events associated with this theme included effective teamwork, having positive team meetings, and helping each other during times of greater need. This finding supports the established view that effective teamwork can be a powerful way of helping patients (

20) and adds to the accumulating evidence of its clinical effect (

21).

The interrelated themes of “staff less pressured/lower workload” and “staff pressure/high workload/stressed” were also significantly associated with score transitions, which adds support to the view that staff burnout results in negative outcomes (

19,

22), particularly given that this is the first study that documents causality. Specifically, these themes included occasions when staff felt more or less stressed, burned out, or pressured than normal. The events associated with these themes were frequently related to bed occupancy and staffing levels (50% shortage of staff causing burnout), and previous research has shown these factors to be associated with conflict levels on acute psychiatric wards (

10).

Negative staff morale was also found to significantly precede score transitions. Examples of this theme included “a patient suicide strongly affects staff morale,” “ward manager is not happy and wants to leave his job as soon as possible,” and “a patient had a still-birth on the ward which upset the staff. The Trust held an inquiry which further affected their spirit.” This finding was expected and supports the breadth of negative outcomes that are often attributed to poor staff morale. These include staff absence and treatment disruption (

23), increased patient-patient and patient-staff violence (

24,

25), and a reduced pool of competency when staff react by migrating to more desirable places (

26).

Conflict between staff was also found to significantly precede conflict and containment score transitions. This included any event where two or more staff members were in conflict with each other. Examples of this theme included statements such as “serious nursing staff tensions” and “an SHO [senior house officer] with a short fuse is unpopular with staff.” The idea that interstaff conflict can lead to disturbed behavior by patients has often been described. However, this is the first time that negative quantitative outcomes have been found to be significantly associated with this factor. Linked with this theme was the significant finding of staff support. Examples of this theme included staff receipt of regular training and supervision and involvement in staff support groups.

The final two significant staff-centered themes were positive and negative staffing changes. These themes included events in which any type of staffing change occurred but also had some sort of positive or negative impact. Examples included “Part-time nurse returns from maternity leave who is unreliable and causes tensions” (negative staff change) and “an outstanding SHO starts working with the consultant” (positive staff change). Staffing changes with no reported impact (“SHO rotation”) were not associated with score transitions. These are also unsurprising findings that again serve to underline the direct influence that staff had on ward life and patient behavior, when they work positively or negatively.

The final theme found to be significantly associated with transitions was “City Nurses intervention running/begins.” This item refers to a year-long intervention that specialist City Nurses delivered on five of the acute psychiatric wards examined in this study during the same time that the PCC-SR data and qualitative interviews were being collected as part of the Tompkins Acute Ward Study. The intervention was therefore distinct from this study but was opportunistically included within the qualitative analysis. The City Nurses worked on bringing about change toward low-conflict, low-containment, and high-therapy nursing by increasing effective ward structure, helping staff to regulate their emotions, and teaching staff how to more positively appreciate patients (

27).

Support for the model

This study's findings support our research program's working model of what determines the likelihood of conflict and containment in acute inpatient psychiatric wards. The model centers on the influence of staff factors, the most important of which are the staff's positive regard for patients, their own emotional self-regulation, and their provision of an effective structure of ward rules and routines. These three factors are influenced by their psychiatric philosophy, moral commitments, technical mastery, teamwork skill, and organizational support. These findings support the model in that most of the significant themes found to precede conflict and containment score transitions were staff centered.

It is unclear how these themes link with the model's components, although it is likely that there are multiple relationships. Positive appreciation is likely to be linked with positive staff practice, because being compassionate and treating patients with value constitutes positive practice. A relationship between emotional regulation and staff morale, staff support, staff-staff conflict, positive teamwork, and staff pressure, stress, and workload level probably exists; compared with other teams, those that support one another and work together effectively without conflict or pressure should be better able to maintain their emotional equilibrium with patients who are considered “difficult.” A ward with an effective structure that includes a well-directed routine and rules that are fairly and consistently applied is likely to be run by a ward manager who is proactive and reinforced by an active team that works positively together. Positive or negative staffing changes are likely to affect all elements of the working model. The finding that the City Nurses intervention was significantly associated with transitions also lends support to the model given that the intervention was constructed on the model's principles (

27).

This study's findings also indicate that a ward's physical environmental influenced conflict and containment. This is a theme that is not currently included within our working model and warrants further empirical investigation.

Strengths and limitations

This study's methodological approach has afforded quantitative patterns in a large and statistically reliable longitudinal data set to be explained by qualitative data. Furthermore, unlike cross-sectional studies, this study enables one to draw inferences about causality because events were matched against time points that preceded score transitions. However, this study's findings can be attributed to accurately represent only approximately a quarter of the possible data because only 27% of the score transitions were successfully matched with qualitative data. Furthermore, we were unable to ascertain how accurate the interviewees' six-month recall of events was, in terms of both what and when events occurred. This means that there remains some uncertainty about the precision between the temporal ordering of the events and the score transitions.

It is also important to consider that the factors identified in this study were inherently linked with the perceptions of the consultant psychiatrists and ward managers. For example, it is not surprising that a theme of poor leadership did not emerge from the interviews. Interviews with patients would have yielded a richer and more balanced qualitative data set of events; however, this was not possible because inpatients in an acute phase of psychiatric illness do not usually remain within the same ward beyond one month.

Another potential limitation of this study was that the marking of the score transitions was a subjective process; however, an interrater reliability test had a good result. In addition, although the overall mean response rate of the PCC-SR was reasonable, there was considerable variation of response rates across the 16 wards. However, conflict and containment rates have been shown to vary up and down across the 16 wards, regardless of response rates (

9). Furthermore, previous research has established that the PCC-SR does not suffer from the underreporting of incidents associated with using official reports (

28).

Another potential criticism is that the findings may be explained by reverse causality (for example, higher conflict leading to lower staff morale). However, this study has shown that across the 16 wards, low staff morale was significantly more likely to precede increases in conflict compared with decreases in conflict. This is a statistical finding across the data set and implies that reverse causality is not a possible explanation for the study findings. However, it is possible that certain factors (such as injuries, absenteeism, staff turnover, high contact census, changes in leadership, and patient volume) may initially influence staff morale. Future research clearly is needed to investigate the influence that such factors have on staff, given that staff have been shown to play a crucial role in influencing the likelihood of conflict and containment rates in this study.

It could also be argued that aggregating conflict behaviors and containment responses into two total scores is too broad a method given the range of severity in conflict behaviors and containment responses. However, previous research has provided evidence that using aggregated scores on the PCC-SR does not undermine the tool's reliability or validity (

7). Finally, although the 40 themes were counted 467 times across the score transitions, for many of the significant themes the counts were fairly small (range 0–19), albeit large enough in each instance to be significant.

Conclusions

The findings of this study emphasize the influence of ward staff in making wards safe environments for acute psychiatric inpatients. Other types of events, particularly those centered on patients, were less likely to prompt increases or decreases in conflict and containment rates. Staff should focus on positive changes they can make to work as a team more effectively, particularly during pressured and stressful times.

The results also imply that any prospective intervention to reduce conflict and containment should include methods centered on enhancing staff practice. Specifically, ward-level interventions should include methods that enhance positive staff practice, increase staff activity (so that staff members are providing care and being visibly useful as frequently as possible), and enhance teamwork, with a focus on increasing team and organizational support levels, team harmony, and proactive leadership. Interventions should also reduce stress and burnout, bolster morale, improve the physical environment (so that it is more conducive to patient care), and help make changes in staffing as functional as possible. The significant staff-staff conflict and staff-support themes also imply that staff should regard each other with a positive attitude, emotionally regulate themselves in response to their colleagues' behavior, and follow an effective set of work rules and routines. By enhancing practice in such ways, crucial clinical and economic gains are likely to be made.