Since its inception 35 years ago, assertive community treatment (ACT) has grown from a single, experimental treatment for people with severe and persistent mental illness (

1) to a core service of many public mental health systems. Reviews of studies of ACT have found that it is more effective than standard community mental health services (

2–

13).

Positive outcomes of ACT include decreased psychiatric hospitalizations, increased housing stability, greater treatment retention, and increased consumer and family satisfaction. More modest associations have been found between ACT and decreased psychiatric symptoms and improved quality of life (

4). Further, high-fidelity ACT teams are cost-effective when serving consumers with the highest hospitalization rates (

10). ACT is recognized as an evidence-based practice (

14–

17); it continues to evolve by incorporating recovery-oriented and other evidence-based practices (

18–

20). ACT has been widely disseminated (

21). Although some mental health systems incorporate basic principles of ACT into standard care rather than implement the full program (

18), 45 states recently reported implementation of ACT or ACT-like services (

22).

Unfortunately, ACT is not always adequately implemented or sustained. Some large-scale ACT implementation projects have been successful (

23,

24) and others less so (

25–

29). One survey found that less than one-third of more than 300 ACT programs satisfied a minimum set of program standards; most failed to implement or drifted away from the program's fundamental principles and operations (

29). Given the positive correlation between fidelity and outcomes (

5,

30,

31), inadequate model implementation suggests less effective services.

Failed implementation and program drift are not unique to ACT. Examples abound in mental health (

32,

33) and other fields (

34), and researchers have begun to systematically evaluate the process of implementing and disseminating evidence-based practices, giving special attention to identifying strategies for successful implementation (

35). Although these are promising developments, failed implementation is only one of a larger set of problems related to poor quality of services in the public mental health system (

18). Additional attention needs to be directed to researching strategies for facilitating successful implementation of new programs and to sustaining the quality of services over time.

Methods

We conducted a selected review of literature published between January 2000 and May 2011 about implementation and sustainability of ACT treatment. The review was guided by searches in PsycINFO and PubMed that used the search term “assertive community treatment” coupled with either “implementation” or “sustainability.”

The review was intended to provide a heuristic model for administrators and providers seeking to implement and sustain high-quality ACT programs. Our approach built upon early recommendations for implementing ACT (

36,

37) and integrated the findings from implementation studies conducted more recently (

23,

38). We also drew upon theories of implementation (

34) and incorporated our observations as ACT researchers, administrators, trainers and consultants, and practitioners.

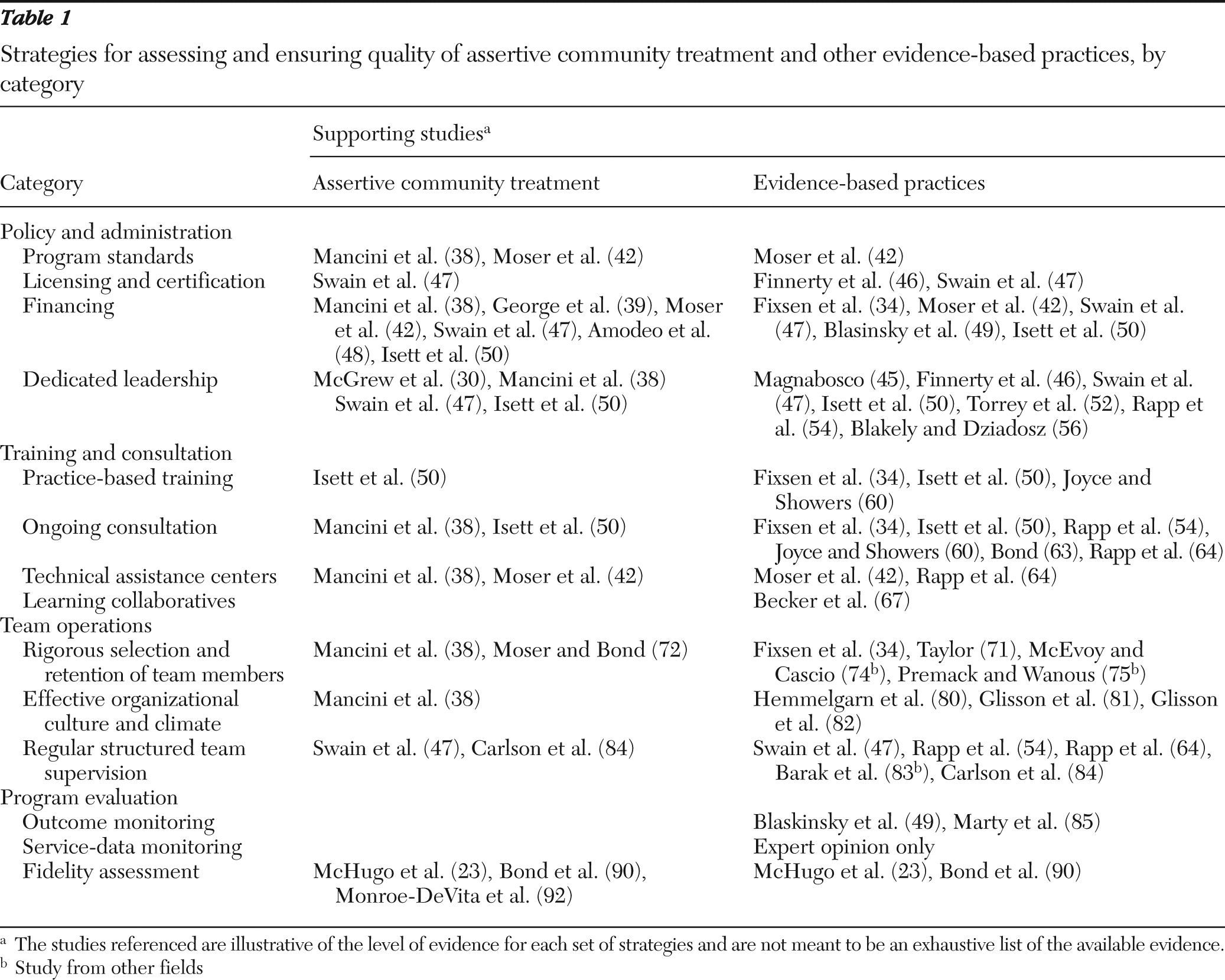

Strategies for assessing and ensuring quality of ACT programs and other evidence-based programs across four broad categories were considered. The categories included policy and administration, training and consultation, team operations, and program evaluation. The individual components of this conceptual model were generally consistent with Fixsen and colleagues' (

34) seven core implementation components but were tailored to ACT, and several emerging and “hypothesized” strategies were added.

Results

The search yielded 57 articles.

Table 1 summarizes the four categories of strategies to promote high-quality ACT and lists examples of supporting studies.

Policy and administration

Program standards.

Program standards should define key program elements of ACT (

39)—for example, staffing, eligibility, organizational structure, and type and intensity of services—and reflect nationally recognized standards for high-quality ACT services. Without clearly defined practice standards, practice variability is common (

40). Therefore, a fundamental first step for ensuring high-quality services is to define ACT program standards (

37,

41). Well-defined state standards emerged as an important factor leading to successful implementation of ACT in Indiana and New York (

38). In Indiana, successful implementation of ACT contrasted sharply with the difficulties faced in implementing integrated programs for treatment of co-occurring substance abuse and mental disorders, which lacked state standards (

42). More recently, Washington State modified the national ACT standards (

36) to provide important enhancements in several areas, including integration of other evidence-based and recovery-oriented practices (

43). Several other states, including Iowa, Minnesota, New York, and Oklahoma, have also promulgated ACT standards.

Licensing and certification.

Although establishing practice standards is a necessary first step in ensuring high-quality implementation, it is not sufficient; without contingencies or incentives, guidelines are often ignored in practice (

44). Implementation of a rigorous process for licensing or certifying programs and linking funding to compliance with licensure standards is another key strategy (

45). Certifying and licensing bodies can require teams to seek additional training and consultation to address areas of deficiency. Close linkage of standards, certification, and funding mechanisms is associated with higher program fidelity (

46) and sustainability (

47).

Financing.

The most common barrier to implementing and sustaining ACT (

39,

48) and other evidence-based practices (

49) is inadequate funding for both start-up, such as recruitment, training materials, and expert consultation, and ongoing implementation. Funding for staff time and for training before serving consumers is critical (

50). Washington State addressed the need for start-up resources by providing ACT teams with funding equivalent to 33% of their annual funding ($1.3 million and $650,000 annually for teams serving 80–100 consumers and 42–50 consumers, respectively [

43]). The funding allowed time for staff recruitment and training and for a gradual enrollment of consumers that gave staff a greater opportunity to master new skills and learn to work within a team-based approach.

Funding strategies that support outreach efforts to consumers who may be difficult to locate or to engage in services, such as people with co-occurring disorders or who are homeless, are particularly crucial for ACT teams. Typical mental health funding reimburses providers for face-to-face service contacts and time with consumers; reliance on such a funding strategy for ACT, however, can unwittingly incentivize provision of services to persons who are most accessible and motivated at the expense of extensive efforts to find, engage, and serve persons who may be challenging to locate and serve. More innovative financing strategies, such as case rates and reimbursement for outreach efforts that do not result in face-to-face contacts, are needed to support efforts to find and engage such persons, who are often a priority group in need of ACT services. More generally, funding for ACT should be designed to support services to persons across all stages of change, from those needing intensive outreach and engagement to those who have made major improvements in functioning and recovery and are transitioning to less intensive services.

Adequate funding is important not only for program start-up but also for sustaining high-quality services (

34,

41,

47). Funding for ongoing implementation is critical for continued training, consultation, and fidelity monitoring (

38). Long term, ACT teams require $10,000 to $15,000 per consumer per year (

51), but the source of funding is as important as the amount. Currently, Medicaid is the most common funding source for ACT (

38,

50); however, given state and federal budget deficits, the viability of Medicaid is currently unpredictable. As such, it is increasingly important to explore the potential to blend Medicaid funding with other sources, such as revenues for substance abuse treatment or housing (

37). Further, as national health care reform takes shape, it will be critical to ensure adequate funding for resource-intensive programs such as ACT.

Dedicated leadership.

Leadership emerged as the most important factor affecting fidelity of implementation in the National Evidence-Based Practices Project (

52). More specifically, having a leader at the state level with responsibility and authority to provide oversight and advocate for the use of a model (

45–

47,

50,

53,

54) is particularly important to implementation; this finding is also true specifically for ACT (

30,

38). The individual who serves as a state ACT leader, a position that may require full-time status (

36), should build and sustain support for ACT among stakeholders (

50,

55), encourage program development and strategic planning (

55), and function as a watchdog for regulatory changes that affect ACT.

At the agency level, leaders are also needed to champion the model, ensure accountability (

37), allocate sufficient team resources and monitor the team's fiscal sustainability (

38), and ensure that preexisting policies and procedures do not interfere with fidelity (

37). These responsibilities do not necessarily lie with one leader and may be shared by both middle and upper management (

38) and supervisors (

56). Further, a knowledgeable, positive team leader who is involved in direct services, enforces team accountability, and encourages independent decision making by team members has also been found to be key to successful ACT implementation (

38).

Training and consultation

Practice-based training.

Most experts recommend the use of didactic training and supplemental written materials (

19,

57), although insufficient alone (

34), to provide background for skills training (

37). Ideally, introductory training is provided to ACT staff, agency and regional management, and other key stakeholders, such as consumers and families. Distance learning, or e-learning, is a growing area in the field (

58) and recent research suggests that it may be a viable option for disseminating didactic training in other evidence-based practices (

59). Although this emerging approach has not been tested within ACT, future research in this area may be indicated, given the need to retrain staff in community mental health settings because of high turnover rates and the expenses associated with in-person training.

After initial orientation to ACT, practice- or skill-based training (

34,

50,

60) in specific ACT interventions and in team operations, such as daily team meetings, individual treatment teams, and weekly consumer schedules, is important. Training is most effective when it is participatory, involving role-play, performance-based feedback, and exercises to learn and practice clinical and team operational skills (

60). Direct observation and modeling, also key strategies (

61), may be facilitated by viewing DVDs (

57,

62) as well as by live demonstration of techniques, for example, by conducting a mock daily team meeting and by shadowing an existing, high-quality ACT team (

37). Booster and new-staff training (

23,

37) are especially important for teams struggling with implementation, fidelity, and staff turnover.

Ongoing consultation.

Introductory training, supplemented only by the use of written materials and infrequent phone-based consultation, has limited effectiveness for overcoming implementation barriers (

63). Training needs to be coupled with frequent, ongoing in vivo consultation and field mentoring (

34,

37,

50,

54,

55,

60,

63,

64) by a skilled and collaborative ACT consultant (

38). Consultation to the state or county mental health authority and the local agency at the earliest stages of project development is recommended (

65). Consultation should include teaching skills and practice to reinforce skills (“practice-based coaching”) in a manner that fits the personal style of team members (

34). Confidence in, and mastery of, new skills can also improve staff attitudes toward implementation and consumer change (

56). Some research suggests that local program trainers should also receive monthly consultation (

23) during start-up. Even mature ACT teams, however, will often require ongoing, periodic consultation and training, especially given the high rate of turnover among staff at community mental health programs (

66).

Technical assistance centers.

The need for regular training and consultation makes it advisable for funders to support a technical assistance center with expertise in ACT. State funding for technical assistance centers has been observed to be beneficial for implementing evidence-based practices (

24,

38,

42,

45,

58,

64). States, typically in partnership with universities, increasingly have developed their own local centers of excellence to provide ongoing training, consultation, fidelity monitoring, and outcome evaluation to support implementation and sustainability of evidence-based practices (

24,

43).

Learning collaboratives.

Facilitating learning in a systematic manner across teams is another emerging strategy to ensure implementation of evidence-based practices (

58,

67). A learning collaborative generally is a multidisciplinary group that learns from experts how to improve performance, implements new learning and observes the results, shares experiences with other practice sites, and reconvenes to plan further practice improvement (

68–

70). A successful supported-employment learning collaborative (

67) provided a possible model for ACT.

Team operations

Rigorous selection and retention of team members.

Careful processes for selection of clinicians are critical for ensuring the quality of any mental health program (

34,

71), including ACT. Empirically based tests for predicting the success of ACT staff do not exist, but research suggests that common positive attributes, such as social intelligence, warmth, flexibility, initiative, persistence, pragmatism, “street smarts,” clinical skills, recovery beliefs, and an ability to work in vivo—in naturalistic community environments—and collaborate with team members (

38,

72,

73), are helpful in providing ACT. Experience in traditional office-based mental health programs is not necessarily a good predictor of success as an ACT team member because ACT involves extensive outreach. In fact, many mental health workers prefer office-based settings (

36). Organizational psychology studies found that realistic job previews—which provide applicants with accurate information about job requirements—modestly improved staff retention (

74,

75). For ACT, realistic job previews should ideally incorporate shadowing community-based staff on other ACT teams.

Successful staffing includes attention to retention. Staff turnover disrupts service delivery and continuity of care and creates a need to repeat costly staff training (

38,

76,

77). Staff burnout is one reason for high turnover (

77,

78). A recent quasi-experimental study of a brief burnout prevention program showed promising results among community health and ACT staff (

79), although additional rigorous research is needed to determine the long-term effects for improving staff retention.

Effective organizational culture and climate.

Organizational readiness to change existing practices in order to implement ACT is key to successful implementation (

24,

38); however, agency or team culture and climate have received little attention in the ACT or the adult mental health implementation literature. Agency willingness to embrace implementation of evidence-based practices and make adjustments in accordance with fidelity was a key factor in successful implementation of ACT in one recent study (

38). Organizational interventions, such as conflict management training, continuous quality improvement processes, and other activities aimed at developing a positive culture and climate, are important determinants of service quality and outcomes (

80–

82) and are promising strategies for implementing and maintaining ACT teams.

Regular, structured team supervision.

Quality is also enhanced if the team leader provides regular and structured supervision to each team member. Studies have found that regular group supervision focused on review of specific cases and on practice of specific skills is key to improving fidelity to evidence-based practices (

54). Follow-up studies found that supervision was one factor related to sustainability of several evidence-based practices (

47,

64). Assistance with specific work tasks, provision of social and emotional support, and interpersonal interaction by a supervisor also have a significant and positive impact on staff outcomes (

83). More recent research points to the effectiveness of specific supervisor behaviors such as modeling, observing, and providing feedback about specific clinical skills; facilitating team meetings; promoting quality improvement activities; and using consumer outcomes to guide supervision (

84).

Program evaluation

Outcome monitoring.

Consumer outcomes are considered essential to evidence-based practices (

85), yet ACT teams rarely collect outcome data (

42). To ensure quality, however, ACT programs should consistently assess consumer outcomes, ensuring that there is a mechanism for receiving specific feedback about clinical outcomes (

49,

61) and applying it in the program's day-to-day work. It is essential to measure a range of consumer outcomes besides psychiatric hospitalization, which is the single dominant outcome measure for ACT (

85), including symptom reduction and substance use, as well as housing, employment, and other measures of recovery (

4,

12,

13,

86). Assessments in these areas can be conducted by staff regularly—for example, during treatment plan reviews—and integrated into collaborative discussions with consumers about recovery goals. Although not routinely conducted by ACT teams, regular assessment of consumers with specific recovery measures such as the Recovery Assessment Scale (

87) should be a focus for ACT in the future.

Service-data monitoring.

Given that the successful implementation of evidence-based practices requires “consistent services in specific dosages and combinations” (

50), it becomes imperative to collect consumer-level service data. Progress notes can be designed to capture data about service delivery, such as frequency, duration, and type of services, and used to prepare reports about key service variables for review by the ACT team and management. Service data can be analyzed both to report aggregate findings, such as average number of weekly contacts, and identify individual outliers, for example, underserved persons. Service data may also be used to check the provision of other evidence-based practices, such as supported-employment services, and problems may be targeted for quality improvement. When analyzed by each consumer, results may be compared with treatment goals, and the level of services may be adjusted as needed to meet personal goals.

More generally, applying health information technology to inform clinical practice, such as collaborative and shared decision making (

88,

89), is a related, emerging area of focus within evidence-based practice implementation (

58). The effectiveness of these technologies within ACT are not yet known but should be explored by future studies.

Fidelity assessment.

One of the most popular and promising strategies for enhancing implementation involves the use of quantitative scales to measure fidelity to a program model (

37,

38,

55,

56,

90). The Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment Scale (DACTS) (

91) is the fidelity scale that has been used most widely for ACT to date.

Merely assessing fidelity, however, is insufficient for enhancing implementation. A systematic approach to providing fidelity feedback to provider agencies was first codified in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project (

23). Twenty-nine (55%) of the 53 sites achieved high fidelity within the two-year follow-up period, and most sites that had successfully implemented their programs had modified services based on feedback from fidelity reviews (

90), suggesting the effectiveness of the fidelity review process. Fidelity reviews have since been used in several states to improve ACT implementation.

Although useful, the DACTS has been found to have several gaps and limitations (

20,

92). An enhanced version of the DACTS, called the Tool for Measurement of Assertive Community Treatment (TMACT) (unpublished measure, Monroe-DeVita M, Moser LL, Teague GB, 2011), has been developed to address many of these limitations. The TMACT has been adopted and piloted in several states, including Washington, New York, Pennsylvania, Nebraska, Florida, and Missouri, as well as in Japan and Norway.

Discussion

At present, no single strategy is adequate for measuring and ensuring the quality of ACT programs (

93). Fidelity measures are especially useful but are insufficient when used in isolation. A multifaceted blend of methods involving policy and administration, training and consultation, team operations, and program evaluation appears to be necessary and can operate synergistically. Resource constraints may cause practical difficulties at present for implementing some strategies. For example, state budgets may limit training, and underfunded fee-for-service systems may find it difficult to set aside staff time to collect outcome data. Still, the strategies outlined here provide a blueprint for what is possible and may be helpful for responding to the increased emphasis on quality of care expected in 2014 under the Affordable Care Act.

Some core strategies for ensuring high-quality ACT—such as program standards, staff training and ongoing consultation, and feedback on implementation, including fidelity assessment—have been previously suggested (

37,

38,

61). However, this article offers several advancements of these efforts, including a greater number of strategies within a single heuristic model to consider for both implementation and ongoing service quality. Further, recommended strategies are based on the results from a number of studies conducted in the past decade, as well as several new strategies identified for field use and research testing within ACT.

These strategies are recommended for ACT, but they are likely to apply across different practices. Indeed, many of the strategies, such as staff selection, training and consultation, and fidelity and outcome evaluation, are also consistent with and support a general theory of implementation of evidence-based practices (

34). However, our review suggests that this model needs to be tailored to ACT by the addition and augmentation of strategies recommended in the ACT and evidence-based practice literature.

Conclusions

The various principles described in this review must still be regarded as working hypotheses because of a lack of rigorous research. The strategies reviewed are supported by some research, often qualitative in nature, and by expert opinion. Implementation science, in general, is in its infancy (

34). Although much has been learned about the dissemination of evidence-based practices since the pioneering National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project (

23), there is a critical need for additional research using rigorous methods to validate strategies for improving services and consumer outcomes. In the meantime, these guidelines provide practical recommendations for practitioners, administrators, and researchers and suggest important domains for measuring and ensuring the quality of ACT.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank the conference organizers of the Symposium Nacional Sobre Tratamiento Asertivo Comunitario en Salud Mental in Avilés, Spain, for their support in preparing an earlier presentation of these findings. The authors also acknowledge Bonnie Barbareck, B.S., and Ashley Hamilton, B.A., for their assistance with the literature review.

Dr. Bond has received research support from Johnson & Johnson Corporate Contributions. The other authors report no competing interests.