Violence and aggression by patients is a well-recognized problem in psychiatric hospitals (

1). Verbal aggression is a common manifestation of psychological disturbance and distress, but physical aggression, particularly more serious acts of violence, are comparatively rare (

2). However, homicides in mental health settings sometimes occur, such as in 2006 when leading schizophrenia researcher Wayne S. Fenton, M.D., tragically died at the hands of a 19-year-old male outpatient (

3). There is an extensive literature about suicide in psychiatric hospitals and a substantial body of research into aggression and violence in health care settings, but relatively little is known about the circumstances of homicides committed by inpatients of psychiatric hospitals.

Homicide in psychiatric hospitals appears to be very rare. Ekblom (

4) reported that there were eight confirmed homicides by patients in Swedish psychiatric hospitals in the ten years between 1955 and 1964. Seven victims were fellow patients, and one was a nurse. Gordon and associates (

5) described the circumstances of five homicides in secure hospitals in England over a period of 30 years and a double homicide by two patients in a secure hospital in Scotland. Pérez-Círceles and associates (

6) reported two homicides over a 13-year period in a 335-bed maximum-security prison hospital in Spain; 34 other deaths were classified as suicide during that same period.

What is known about the characteristics and circumstances of inpatient homicide comes from a very small number of published case reports. Two case reports have described homicides by recently admitted and acutely psychotic patients, whose victims were older and more chronically mentally ill (

7,

8). Another report described the violent homicide of a vulnerable patient by a severely ill fellow patient in an overcrowded chronic ward (

9). Several case reports noted the assailant's claim that the victim wanted to die or deserved to die (

5). Other published case reports described the homicides of doctors, nurses, and other mental health professionals (

10–

12). A common theme in the published reports has been the devastating effect that homicides have on staff morale and other aspects of the mental health service (

7,

9,

11,

12).

Our aim was to identify and describe homicides that occurred in psychiatric facilities in the states and territories of Australia and in New Zealand in the past 25 years.

Methods

The Human Research and Ethics Committee of St. Vincent's Hospital approved the study. A modified version of the small-world method for accessing socially and geographically remote information (

13), referred to here as an acquaintance chain method, was used to identify clinicians who knew details of cases in Australia and New Zealand that were not known to the first author or had not been the subject of a published case report. Two experienced clinicians who had worked in forensic services in each of the states and territories of Australia and in New Zealand were contacted and asked whether they knew of a case of inpatient homicide and to suggest the contact details of a person whom they thought might have personal knowledge of a case.

Cases were included if the homicide was committed within a psychiatric hospital ward by a current inpatient. This narrow definition of homicide, which excluded homicides by patients who were on approved or unapproved leave, was chosen because homicides outside the supervision of hospital staff might be less memorable and could have more in common with homicides committed in the community. A case of an outpatient who killed a doctor was the subject of a published case report (

12) and was also excluded.

Results

Documents relating to the cases from Australia and New Zealand were located after senior clinicians in each region identified the cases. A total of 13 clinicians were contacted in the initial round and were considered primary contacts; several had worked in more than one region. An additional 11 clinicians were contacted by the acquaintance chain method and were considered secondary or tertiary contacts. Most of the names suggested by the primary contacts were other primary contacts, and after three rounds of following up with identified contacts, no further cases or names of clinicians who might have had knowledge of an inpatient homicide were identified. The first author had assessed five cases in the course of preparing reports for court proceedings, and the details of one additional case were obtained for an earlier study of homicide and mental illness (

14). A detailed description of another case was obtained from the coroner's inquest report.

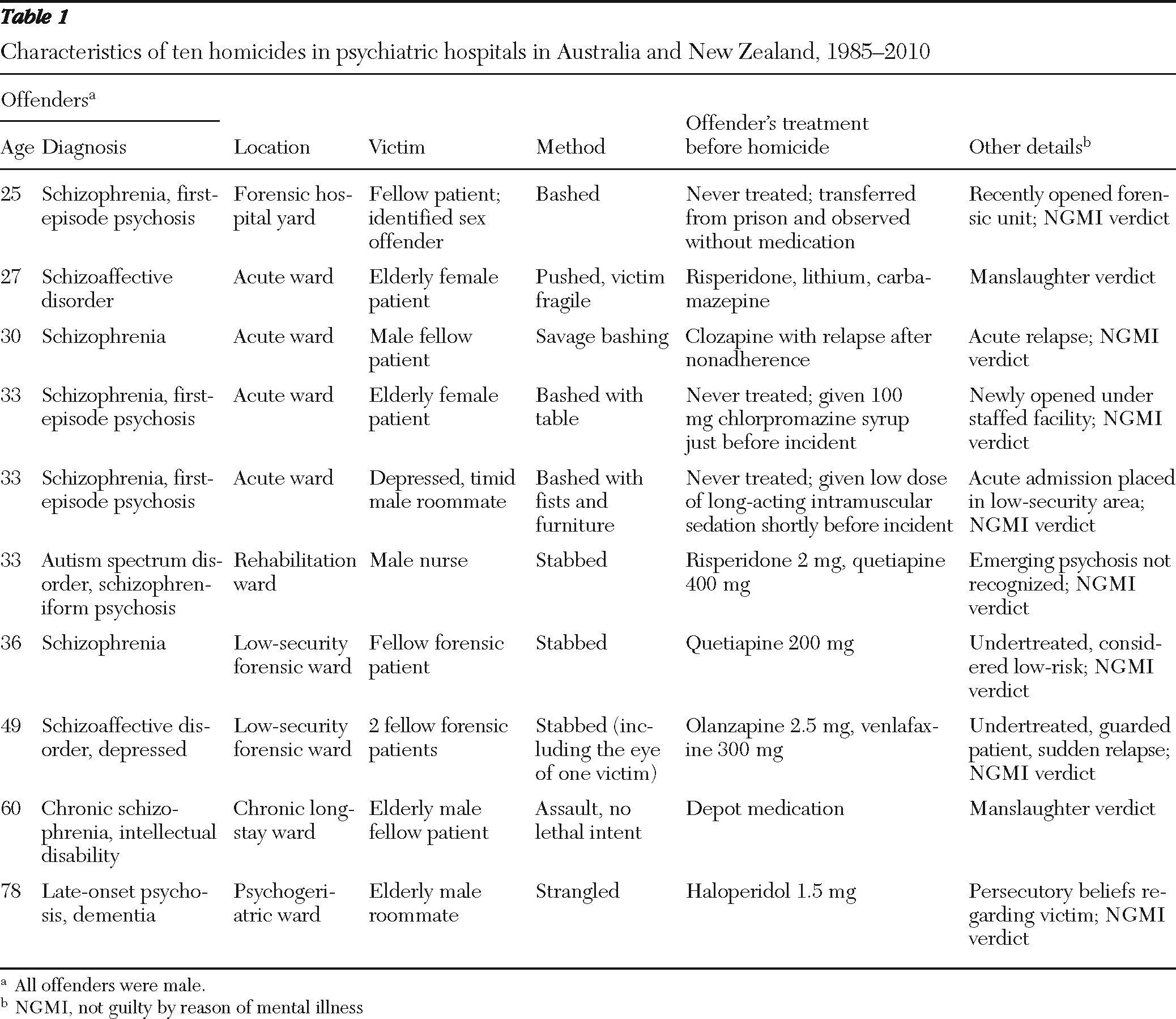

The acquaintance chain method identified ten episodes of homicide by patients in psychiatric hospitals in Australia and New Zealand since 1985. Five occurred in New South Wales, one in Victoria, one in South Australia, and one in Queensland, Australia; two occurred in New Zealand. Senior clinicians working in Western Australia, Tasmania, the Northern Territory, and the Australian Capital Territory were not aware of any cases of inpatient homicide in those states and territories in the past 25 years. The ten cases from Australia and New Zealand, with 11 victims, are described in

Table 1.

Homicide rates in psychiatric hospitals were estimated with data from the

World Health Organisation Project Atlas (

15). In 2004 there were 3.9 psychiatric beds per 10,000 people in Australia and 3.8 beds per 10,000 in New Zealand. This suggests rates of four homicides per 100,000 bed-years in Australia and 5.3 per 100,000 bed-years in New Zealand. However, these figures are only estimates, because of the small number of homicides and the fall in the number of psychiatric beds in Australia and New Zealand during the 20 years prior to 2004.

Discussion

Inpatient homicides in Australia and New Zealand are very rare events. We estimated the rate to be between four and five per 100,000 bed-years, a figure that is nevertheless several times higher than the rates of homicide per 100,000 people in Australia and New Zealand. None of the cases we identified were the subject of a published case report. The absence of any published case reports of inpatient homicide since 2003 suggests a bias against the submission or publication of case reports on this topic and is not due to a decline in these tragic events.

Although a number of the published case reports were about the homicides of staff members, the results of this study suggest that most of the victims of homicides committed in psychiatric hospitals were fellow patients. Ten of the 11 victims in our study were patients, and one was a nurse—a finding that was similar to that of the study from Sweden, where seven of the eight victims were patients and one victim was a nurse (

4). This finding suggests that fellow psychiatric inpatients are most at risk of lethal assault within a hospital. In this sense, other psychiatric inpatients carry the risk of violence arising from the hospitalization of dangerous patients detained under mental health laws for the protection of the community.

An examination of the circumstances of the homicides in the published case reports and the circumstances of the ten cases from Australia and New Zealand suggests that inpatient homicides fell into three main groups. The first is homicide by acutely psychotic patients recently admitted to a hospital. Our sample included two patients in their first episode of psychosis who killed fellow patients with great violence on the day of admission. Another patient in first-episode psychosis did not receive treatment with antipsychotic medication and killed a fellow patient while being observed in a secure ward. Two patients with chronic mental illness killed fellow patients during acute exacerbations of illness. In several cases, the initial dose of antipsychotic treatment was considered to be inadequate. These cases were similar to the cases reported by Modestin and Böker (

7) and Cournos (

8).

In the second group of inpatient homicides, the offenders were patients with a history of serious violence who were housed in secure hospitals and forensic facilities. Several of the patients in our study had been found not guilty of violent offenses, had been transferred to lower-security forensic facilities, and were taking antipsychotic medication at doses that were, in retrospect, subtherapeutic. The three cases of homicide in forensic settings from Australia had similarities to the case reports from secure hospitals in the United Kingdom (

5).

In the third group, the offenders who killed vulnerable fellow patients were patients in long-term care with chronic illness, specifically dementia or intellectual disability and comorbid psychotic illness. In two of the cases, the assaults were not thought to have been committed with lethal intent, but deaths occurred because of the frail state of the victims. These cases are in some ways similar to cases of resident-to-resident violence reported in nursing homes. The victims in the forensic facilities all had a history of serious violence and were themselves potentially dangerous. However, in most of the other cases, the victims were frail, elderly, or in other ways more vulnerable than the assailants.

Several of these events took place in facilities that had only recently been opened, when it seemed the procedures for providing surveillance and physical containment of violent patients had not been fully tested. For example, an acutely mentally ill patient with first-episode psychosis was dropped off at the door of a newly opened and understaffed facility in a rural setting. His behavior alarmed the predominantly female staff members, who fled from the ward after locking the patient inside and waited for assistance. In another case, a lethal assault took place in a newly opened forensic facility in a corner of an exercise area that was found to be out of the view of surveillance cameras.

The limitations of this study include the small number of cases and the unique circumstances of each case. A study with a larger number of cases might include homicides that did do not fall neatly into any of the three categories we describe and would provide a more reliable figure for the rate of homicide in psychiatric hospitals.

Despite the very low rate of inpatient homicide in Australia and New Zealand, most experienced clinicians could probably think of an episode of violence by an acutely disturbed patient within a psychiatric facility in which serious injury or even death was avoided by the implementation of proper security procedures. Most clinicians could also recall instances in which long-term patients had exacerbations of illness after antipsychotic treatment was reduced to a subtherapeutic level, demonstrating the need for long-term treatment with an adequate dose of medication for patients with a history of severe violence during previous acute episodes of illness.

Conclusions

Homicides in psychiatric units are rare but devastating events. This review should alert clinicians to three groups of patients who pose a particular risk of lethal assault: acutely disturbed newly admitted patients, undertreated patients with a history of serious violence during acute exacerbations of illness, and confused and disturbed patients with dementia or intellectual disability who are held in low-security settings with other vulnerable patients. The findings of this study should also serve to remind clinicians of the need for adequate procedures to protect patients and staff from serious assault by patients with acute mental illness, in particular the frail and vulnerable patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank the following clinicians for responding to inquiries about cases in Australia and New Zealand: Adam Brett, Phil Brinded, David Chaplow, Gordon Elliot, Greg Hugh, Bill Kingswell, Joan Lawrence, Bill Lucas, Robert Moyle, Paul Mullen, Ken O'Brien, Jeremy O'Dea, Robert Parker, Martin Patfield, Steven Patchett, Stephen Rosenman, Ian Sale, Peter Shea, Alexander Simpson, Terry Stedman, Daniel Sullivan, Rees Tapsell, Maria Tomasic, and Bruce Westmore.

The authors report receipt of speakers' fees from AstraZeneca.