Schizophrenia affects more than 1.5 million people in the United States (

1) and represents a significant economic burden. The annual costs of schizophrenia were estimated to be $62.7 billion in 2002 alone (

2). Proper management of schizophrenia with antipsychotic drugs can improve symptoms and reduce disease burden (

3). However, antipsychotic nonadherence is common (

4–

9) and is associated with increased emergency department visits, inpatient hospitalizations, and costs (

5,

10–

12). In the United States, costs of inpatient care related to antipsychotic nonadherence in 2005 were estimated to be nearly $1.5 billion (

10).

By contributing to deficits in cognitive flexibility, concentration, and memory, antipsychotic nonadherence also has an impact on the treatment of other conditions (

13,

14). This effect is particularly concerning because patients with schizophrenia receive disproportionately worse general medical care and have poorer outcomes than patients with other mental illnesses (

7,

15–

18).

Nonadherence may be especially important in the self-management of cardiometabolic health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia (

19,

20) because coronary heart disease contributes to decreased life expectancy among patients with schizophrenia (

21). The risk of cardiovascular mortality among patients with schizophrenia is roughly double the risk in the general population (

22). Factors such as smoking, sedentary lifestyle, poor dietary habits, and obesity are believed to contribute to heart disease risk among patients with schizophrenia (

23), but it is unclear whether nonadherence to antipsychotic treatment plays a role in cardiovascular health (

24). Nonadherence to antipsychotics may have an adverse cascading impact on nonadherence to cardiometabolic medications, which is known to be related to increased risk of hospitalization and higher health care costs (

25).

Previous studies have compared adherence across antipsychotics and medications for comorbid illnesses (

9,

13,

26) and examined the relationship of antipsychotic nonadherence with hospitalizations, functional outcomes, and costs (

10,

27–

29). However, the relationship between antipsychotic adherence and adherence to cardiometabolic medications among patients with schizophrenia is unclear. One study reported that rates of adherence to antipsychotics and to nonpsychiatric medications are uncorrelated (

9), a second study found a modest correlation between antipsychotic adherence and adherence to diabetes and antihypertensive medications (

13), and another study found that antipsychotic nonadherence predicted nonadherence to diabetes medication (

26).

This study assessed associations between antipsychotic adherence and adherence to cardiometabolic medication among patients with schizophrenia and at least one cardiometabolic condition. It also evaluated the association between adherence to antipsychotic and cardiometabolic medications and health care utilization and costs.

Methods

Study design and data

We conducted a cross-sectional time-series study from 2004 to 2008 of Medicaid patients with schizophrenia and comorbid cardiometabolic conditions. We chose a prevalent user cohort design to provide generalizable snapshots of a population of Medicaid beneficiaries that was large enough to enable sufficiently powered analyses of adherence, utilization, and expenditure patterns (

30–

32).

Medicaid claims data were obtained from Thomson Reuters MarketScan Medicaid files, which contain details about enrollment, prescription claims, inpatient admissions, inpatient facility records, and outpatient claims for approximately seven million beneficiaries of multiple Medicaid programs. Specific states contributing data to Thomson Reuters are not identifiable.

Population selection

Patients with schizophrenia were defined as having one inpatient or two or more outpatient visits with

ICD-9-CM codes 295.1–295.3, 295.6, or 295.9 during each annual cross-section (

33). Patients who were dually enrolled in Medicare, younger than 18 or older than 64, not continuously enrolled in Medicaid during the year assessed, or without drug coverage for the entire year were excluded. Because we were interested in all patients with schizophrenia rather than just newly diagnosed or newly treated schizophrenia, we included patients that met inclusion criteria in any year. Patients could be counted in the analysis during more than one year because excluding patients after their first year of observation would have biased our sample toward patients earlier in their disease, especially during later years of the time period we studied. We restricted the sample to users of second-generation antipsychotics because they are the most commonly prescribed medications for schizophrenia. We excluded patients using long-acting injectable antipsychotics because of the challenges of measuring adherence to these products. The final sample represented annual snapshots of patients with schizophrenia using oral second-generation antipsychotics in 2004–2008.

Patients were further categorized on the basis of antipsychotic medication use; diagnoses of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension; and use of medications to treat a cardiometabolic condition. Comorbid conditions were identified as having at least one inpatient or two outpatient claims for hypertension (

ICD-9-CM codes 401.xx–405.xx), hyperlipidemia (272.xx), and diabetes (250.xx). Cardiometabolic medications included all oral medications for diabetes (metformin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, and other categories); statins for hyperlipidemia; and antihypertensive medications classified as angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics, including loop, thiazide, and potassium-sparing categories of diuretic therapy (

34).

Outcomes

The outcomes included medication adherence, utilization of health services for all causes, and expenditures for health services for all causes. Adherence to oral second-generation antipsychotics, oral antidiabetes medications, statins, and antihypertensives was measured as the proportion of days covered (PDC), which captures the number of days in a year without gaps in medication coverage divided by the number of days observed in the same year. The PDC measure has been shown to perform particularly well as a measure of adherence to antipsychotic medications by individuals with schizophrenia (

35). The PDC measurement interval for a given patient began on the date of the first prescription observed of each medication in each year and continued through the end of that year. The days' supply of each prescription was added to the actual date that the prescription was dispensed to calculate the next scheduled fill date. Periods were considered gaps in the PDC metric if there was no medication available for any drug within each therapeutic class. This therapeutic class-based measure accommodated problems with measuring patient switching and the use of two or more medications simultaneously but may overestimate actual adherence. The PDC ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 representing no medication use and 1 representing perfect adherence (

36). Patients were designated as adherent or nonadherent by using a PDC cut-point of .8, which has been shown previously to predict health outcomes resulting from adherence (

37).

No classes of second-generation antipsychotics, including low-dose quetiapine, were excluded. Adherence to cardiometabolic medication by the pooled cardiometabolic cohort was calculated as an unweighted average of PDC of the three classes of cardiometabolic drugs.

Health service utilization outcomes included annual counts of outpatient visits for all causes, emergency visits, and inpatient admissions. Health services were identified as unique visits per date of service to any provider. Health expenditure outcomes included payments for prescriptions and for inpatient, outpatient, and emergency visits during each year. Health expenditures were inflation-adjusted to 2008 dollars.

Explanatory variables

The explanatory variable of interest was adherence to antipsychotics. We controlled for age group (18–34, 35–54, and 55 and older), race (white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, and other or missing), male gender, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score (

38), and Medicaid eligibility that was due to blindness or disability. Possible scores on the CCI range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating more comorbidity and, therefore, greater risk of one-year mortality. We also controlled for characteristics of the Medicaid plan that provided a prescription copayment for antipsychotics, provider capitation, and state mental health substance abuse treatment coverage. In addition, we controlled for having a history of visits to a psychiatrist or for psychotherapy at baseline as a proxy for schizophrenia severity. Finally, we constructed indicators for type of second-generation antipsychotic initiated, which allowed us to control for patterns of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy.

Statistical analysis

We evaluated adherence to antipsychotic medications and cardiometabolic medications by patients in each annual cross-section and by patients pooled across all years. We also compared adherence to medications among patients by demographic characteristics, treatment, and comorbid condition for each annual cross-section and in a pooled population. For unadjusted and regression analyses, we partitioned the sample into four groups: adherent to antipsychotics and cardiometabolic medications, adherent to antipsychotics and nonadherent to cardiometabolic medications, nonadherent to antipsychotics and adherent to cardiometabolic medications, and nonadherent to both antipsychotics and cardiometabolic medications. Comparisons across the four groups were made by using t tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables.

The unadjusted mean number of emergency visits, inpatient admissions, and outpatient visits per year by the four adherence groups were compared. Similarly, unadjusted total payments for these services as well as for prescription drugs were assessed by using descriptive and bivariate statistics. The likelihood of inpatient admissions and emergency visits was estimated with random effects logistic regression. Results are reported as odds ratios. The number of emergency visits, outpatient visits, and inpatient hospitalizations was estimated with random-effects negative binomial regression to account for the overdispersion of these outcomes.

To examine the relationship between the four adherence groups and expenditures for services, we prepared generalized estimating equations (GEEs) that accounted for the proportion of the groups that did not use the service and the distribution of users of the service among the four adherence groups. Outpatient, medication, and overall expenditures were estimated by using one-part GEEs with gamma distributions and log link functions to account for kurtosis. Inpatient and emergency expenditures were estimated by using two-part GEEs to account for the high proportion of nonusers. For the first-part model that estimated the probability of using emergency services or of being admitted, we estimated GEEs with a binomial distribution and logit link function. For the second-part model that estimated the level of expenditures among users, we estimated GEEs with gamma distributions and log link functions. All expenditure outcomes are reported as inflation-adjusted dollars for the exponentiated linear prediction.

Each regression adjusted for age, sex, race, capitation, use of medication copay, use of psychotherapy, use of psychiatrist, coverage of mental health and substance abuse treatment services, specific antipsychotic medications, CCI score, number of comorbid metabolic conditions (diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension), and calendar year. For all outcomes, a sensitivity analysis considered patients with comorbid diabetes, patients with comorbid hypertension, and patients with comorbid hyperlipidemia. [The results of the analysis are available online as a data supplement to this report.]

Specifically for the expenditure models, two additional sensitivity analyses explored whether conclusions were robust in relation to our sampling approach or covariate adjustment. [The results of the analyses are available in an online appendix to this report.]

The first sensitivity analysis excluded patients in capitated plans and patients with no coverage for mental health and substance abuse treatment services because these factors may influence expenditures. The second sensitivity analysis used this restricted sample but also removed covariates for visits with a psychiatrist and use of psychotherapy because these variables might reflect behaviors associated with medication adherence. This model also removed cardiometabolic cohort count indicators that measured the number of cardiometabolic conditions of each patient. Removing these indicators explored the potential that we might be overadjusting regression models by counting comorbidity with both the CCI and the cardiometabolic condition count indicator.

All analyses represent associations because our use of a time-series design with a cross-section of prevalent users did not allow us to control for temporal relationships between adherence behaviors and use of services. Human subjects approval was obtained from the Western Institutional Review Board, an independent commercial institutional review board located in Olympia, Washington.

Results

We identified 87,015 unique patients with schizophrenia taking at least one antipsychotic medication between 2004 and 2008. Of these, 14.2% (N=12,349) had diabetes, 28.6% (N=24,843) had hypertension, and 12.5% (N=10,909) had hyperlipidemia. The overall prevalence of any comorbid cardiometabolic condition was 42.9% (N=9,169) in 2004 and increased steadily to 52.1% (N=9,001) in 2008. [Further details about the sample are available in an online appendix to this report.]

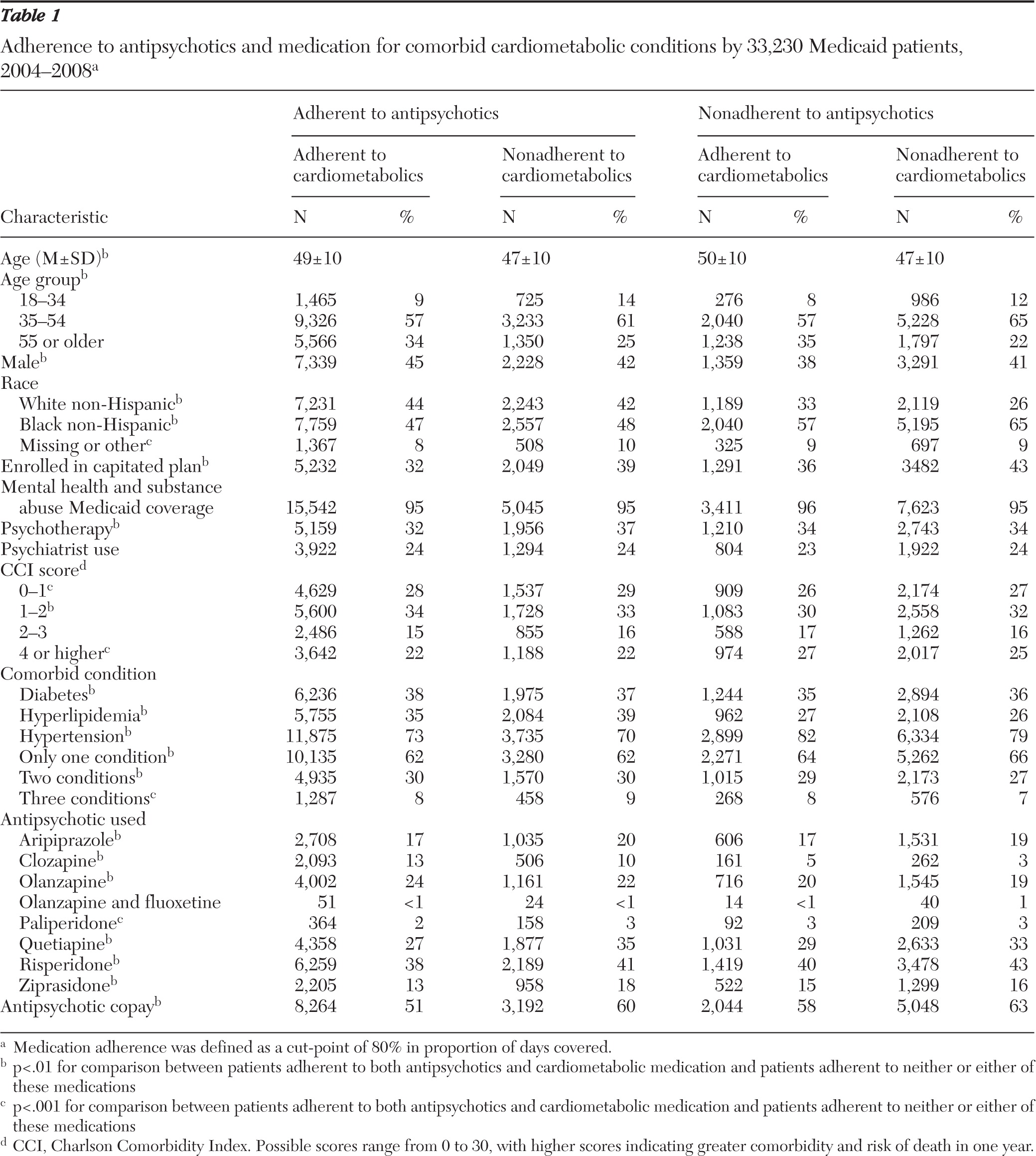

A total of 33,230 (38%) patients used cardiometabolic medications for diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or hypertension (

Table 1). The mean±SD age was 48±10 years, 43% (N=14,217) were male, and 53% (N=17,551) were black. Hypertension was the most common of the treated comorbidities (N=24,843, 75%), followed by diabetes (N=12,349, 37%) and hyperlipidemia (N=10,909, 33%). Most (N=20,948, 63%) patients had just one of the three comorbid conditions; 9,693 (29%) had two conditions, and 2,589 (8%) had all three conditions. Statistically significant differences (p<.05) among the four adherence groups for nearly all covariates were found. Differences between the groups in sex, race, capitated insurance coverage, psychotherapy use, rates of hyperlipidemia and hypertension, and antipsychotic copay were noteworthy.

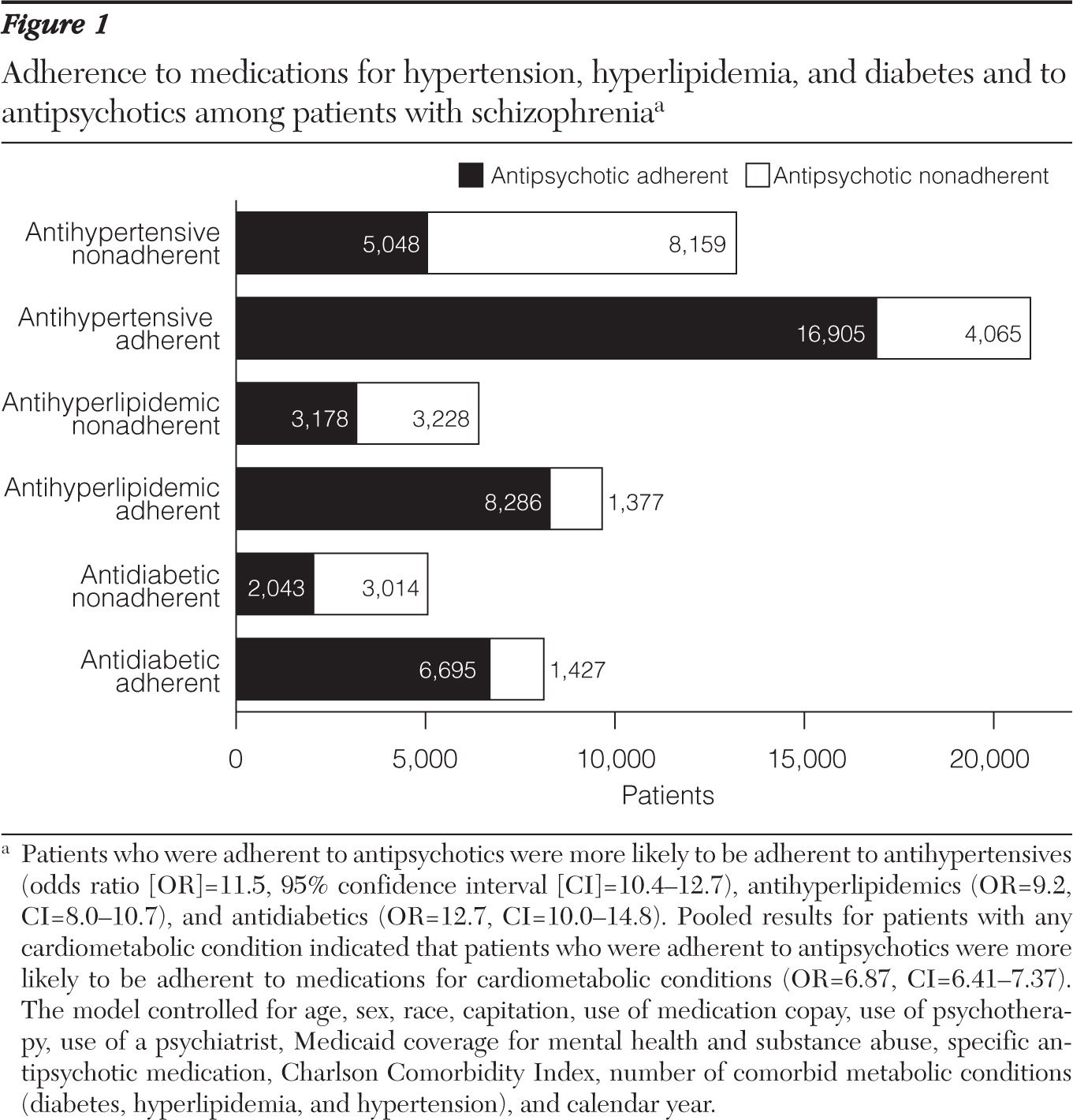

Over all years, 65.2% (N=21,665) of antipsychotic users were classified as adherent. Among patients prescribed a cardiometabolic drug, 60.6% (N=7,480) of patients prescribed diabetes medication, 59.5% (N=14,774) of those prescribed antihypertensives, and 61.6% (N=6,717) of those prescribed antihyperlipidemics were classified as adherent to the cardiometabolic medication. Among patients in the pooled sample, the odds of being adherent to cardiometabolic medications were significantly greater among patients who were adherent to antipsychotics than among patients who were not (AOR=6.9, 95% confidence interval [CI]=6.4–7.4) (

Figure 1). The AORs comparing antipsychotic adherence among patients who were or were not adherent to cardiometabolic medication were 12.7 for diabetes medications, 9.2 for antihyperlipidemic medications, and 11.5 for antihypertensive medications.

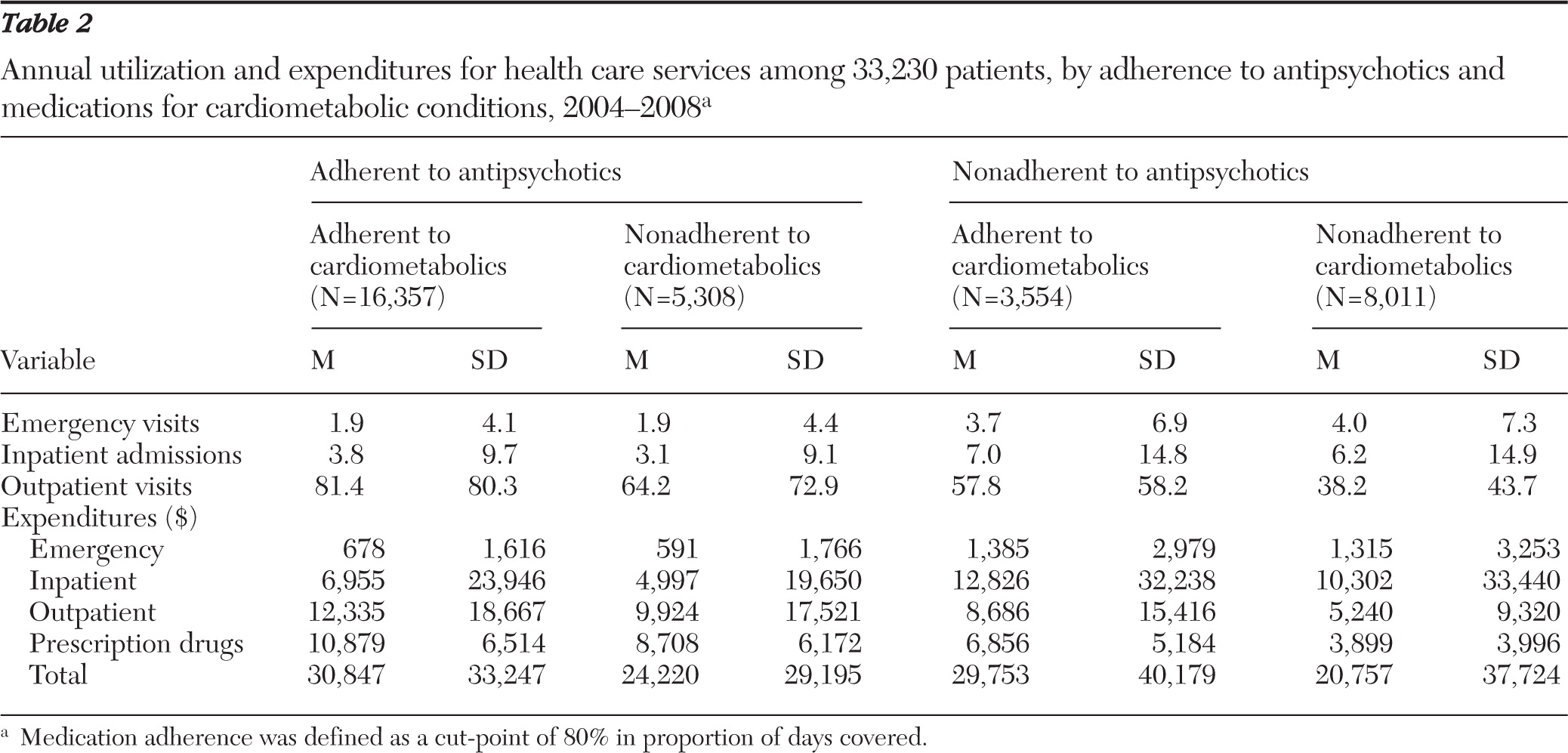

The adjusted number of emergency visits and inpatient admissions was roughly double among the patients who were not adherent to antipsychotics compared with the adherent group (

Table 2), but the adherent group had more outpatient visits. Expenditures paralleled this pattern. Mean unadjusted one-year total expenditures were highest for the group that was fully adherent to antipsychotics and cardiometabolic medications ($30,847) and lowest for the group that was fully nonadherent to antipsychotics and cardiometabolic medications ($20,757).

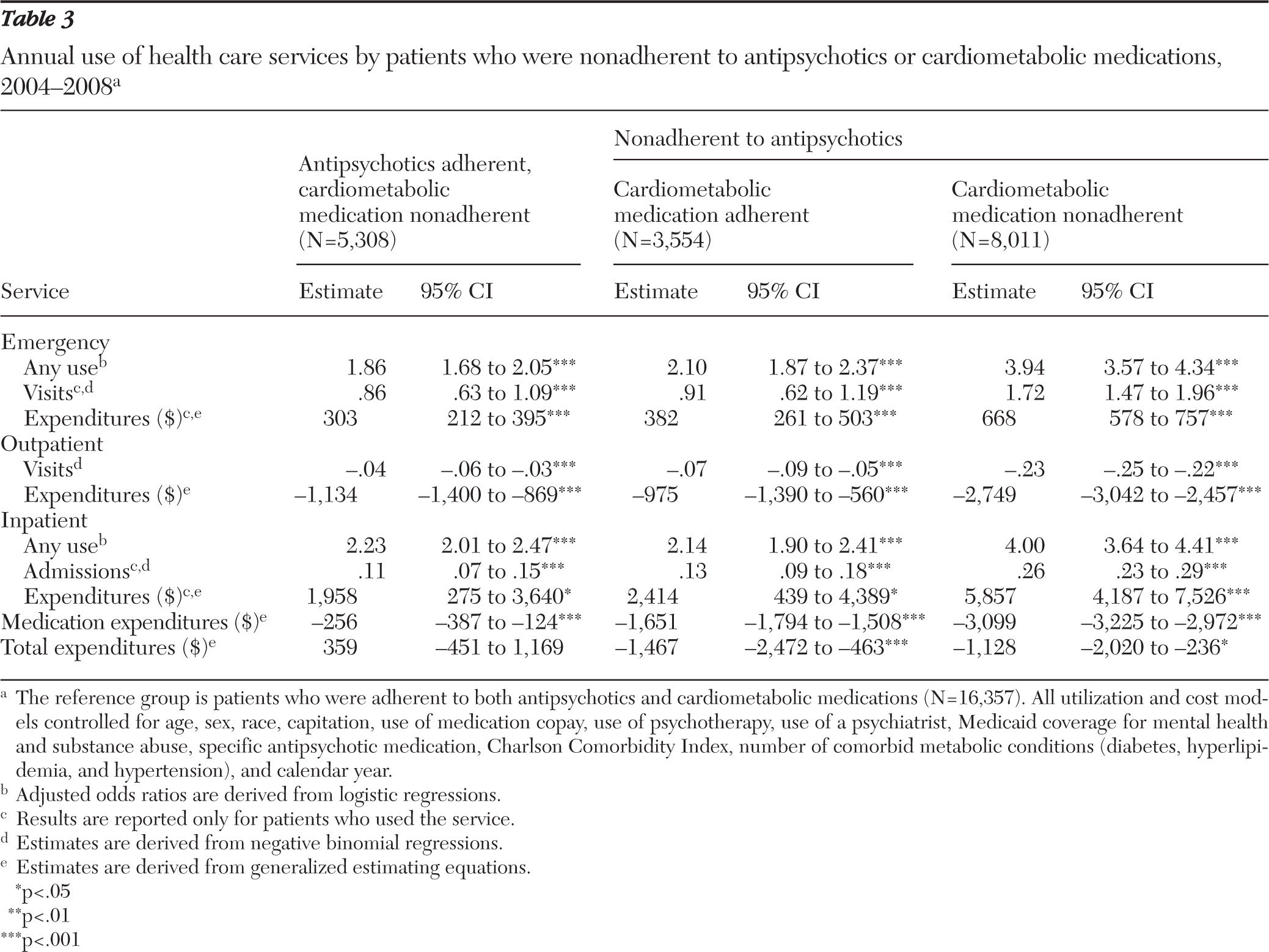

Patients who were adherent to antipsychotic and cardiometabolic medications were modeled as the reference group in analyses comparing health care service use and costs among the other adherence groups (

Table 3). In these analyses, relatively infrequent outcomes such as emergency visits and inpatient admissions were first modeled as the risk of having a visit among all patients. Subsequent analyses estimated the number of visits and expenditures among users compared with the fully adherent group. Because outpatient visits were relatively common, only the number of visits and expenditures were modeled. Medication expenditures and total expenditures were modeled for all patients.

Patients who were nonadherent to both drug types had the greatest increase in risk of emergency visits (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=3.9) and inpatient admissions (AOR=4.0). Smaller but significant increases in risk of emergency visits and inpatient admissions were observed for patients who were adherent to antipsychotics but not cardiometabolic medications (emergency visits, AOR=1.9; inpatient admissions, AOR=2.2) as well as for patients who were nonadherent to antipsychotic medications but adherent to cardiometabolic medications (emergency visits, AOR=2.1; inpatient admissions (AOR=2.1).

Adjusted annual expenditures for emergency visits and inpatient admissions were higher for patients who were nonadherent to either antipsychotic or cardiometabolic medications and were highest for the patients who were nonadherent to both groups of medications. Expenditures for emergency visits ($668), inpatient admissions ($5,857), outpatient visits (−$2,749), and medication (−$3,099) were lower for fully nonadherent patients than for patients adherent to antipsychotic and cardiometabolic medications. Overall health care expenditures were lower for patients who were adherent to neither cardiometabolic or antipsychotic medications (−$1,128) and for patients who were adherent to cardiometabolic medications but not antipsychotic medications (−$1,467). Results did not statistically significantly change in sensitivity analyses of the sampling approach and covariate adjustment.

Discussion

Approximately 36% of patients with schizophrenia in our sample were classified as nonadherent to antipsychotic medication, which is lower than the 50% nonadherence rate reported in the literature (

4–

9). We also found that adherence to antipsychotics and adherence to cardiometabolic medications were strongly related. The magnitude of the association of antipsychotic adherence and cardiometabolic medication adherence observed in our study (OR=6.9, p<.001) was larger than the association observed in two previous studies of antipsychotics, antidiabetics, and antihypertensives (

9,

13), but the direction of the associations was relatively consistent.

The possible implications of antipsychotic nonadherence are particularly interesting, especially given the strong relationship between antipsychotic and cardiometabolic nonadherence. Our results suggest that antipsychotic nonadherence may contribute substantially to emergency visits and hospitalizations. Compared with patients who were adherent to both antipsychotics and medications for cardiometabolic conditions, patients who were nonadherent to one or more classes had a higher likelihood of emergency visits and a hospitalization.

Health care expenditures were similar for patients who were adherent to antipsychotics but nonadherent to cardiometabolic medications and for fully adherent patients. Patients who were nonadherent to antipsychotics and adherent to medications for cardiometabolic conditions had lower overall health care expenditures than fully adherent patients. Although this is partly accounted for by reduced medication costs and fewer outpatient visits associated with schizophrenia management, antipsychotic nonadherence was associated with a greater increase in emergency visits and inpatient care than was cardiometabolic medication nonadherence. Emergency visits and inpatient costs of the fully nonadherent group were even more dramatically increased, illustrating the compounded effects of nonadherence.

Patients who were adherent to antipsychotics were at reduced risk for use of acute, costly services, including emergency visits and inpatient admissions, which translated into lower expenditures for these services. Our finding is consistent with several previous studies (

5,

10–

12). Reduced health service utilization and lower health expenditures may be indicative of better drug treatment, which could reduce the need for intensive health care resources (use of emergency or inpatient facilities). However, patients who adhered to antipsychotic medication had significantly more outpatient visits, and their drug expenditures were proportionally higher because of their better adherence. These higher costs more than offset the lower emergency and inpatient expenditures.

The higher outpatient service utilization of patients who were adherent to antipsychotic medications may be related to behavioral or disease management factors. For example, it might be reflective of the need to closely monitor antipsychotic treatments. Consensus guidelines recommend monthly to quarterly monitoring of weight, blood pressure, blood sugar, and lipids to avoid the potential adverse effects of antipsychotic medications (

39). Because we cannot be certain our findings were related to these factors, nor differentiate which expenditures were attributed to psychiatric or cardiometabolic factors, future studies should explore the sources of increased expenditures by types of nonadherence.

Three plausible reasons may explain the increased prevalence, from 43% to 53%, of cardiometabolic conditions over a five-year period. First, the uptick might be reflective of underlying changes in the Medicaid population that were not captured in our data. We observed a significant reduction in the schizophrenia population from 2006 (N=20,723) to 2007 (N=16,910), which may reflect changes in state eligibility requirements that were not captured in our data. These changes could influence the severity of mental illness among patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia or the cardiometabolic risk of patients with schizophrenia. Second, increasing attention to cardiometabolic risk from research such as the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) may have increased rates of screening for cardiometabolic conditions among antipsychotic users (

40). This would represent an increase in diagnosis and treatment of previously undiagnosed conditions, not necessarily an increase in the prevalence of these conditions.

Finally, an actual increase in the risk of cardiometabolic effects resulting from antipsychotic medication use might be a contributor. Antipsychotic medications, and in particular second-generation antipsychotic agents, have been linked to weight gain, disruptions in glucose metabolism, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia (

40,

41). Growing concern and management of these potential problems might also have increased diagnosis or treatment of cardiometabolic conditions.

This study had several limitations. First, we did not examine the temporal relationship between antipsychotic and cardiometabolic medication adherence in our annual cross-sections. Further, our pooling of annual cross-sections of patients likely resulted in counting some patients more than once, allowing their adherence and service use to vary by year. We controlled for year in our analyses, but we were unable to adjust for individual-level clustering of observations, which could result in modestly smaller confidence intervals for our estimates.

Second, a primary outcome in this study was medication adherence, which was measured using pharmacy administrative claims data. Use of these data to measure adherence assumes that patients who obtain medications actually take them. Third, by virtue of requiring drug use, our study population could be biased to reflect more adherent patients. This phenomenon could be reflected in measures of adherence to both antipsychotic and cardiometabolic medication. Fourth, our measurement of health care utilization and expenditures covered only relatively short, one-year intervals. Given the likely long-term benefits of antipsychotic and cardiometabolic medication adherence, it is possible we underestimated the positive effects and long-term cost reductions associated with being adherent.

Fifth, adherence may be affected by the types of services and expenditures patients receive for treatment of schizophrenia and cardiometabolic conditions, but we did not attempt to differentiate adherence rates by categories of services and expenditures. Finally, unobservable factors could have influenced our study findings. For example, patient self-efficacy (a belief that medication adherence will improve one's health) or social support may influence the decision to use both antipsychotic and cardiometabolic medications. Future studies could use primary data collection to capture the influence of other variables on the relationships examined by this study.

Our study supports the need for interventions targeting medication adherence by patients with schizophrenia and comorbid cardiometabolic conditions. Such interventions might specifically target patients who have demonstrated problems with adherence and have the potential to improve medication adherence by Medicaid patients with schizophrenia and comorbid cardiometabolic conditions. Such adherence improvement might translate into reduced use of emergency visits and inpatient admissions (

42). Approaches that use pharmacy claims to screen for nonadherence may be one option, given that these approaches have been shown to efficiently and accurately identify patients at risk (

5,

43).

Conclusions

Based on analysis of annual cross-sections of Medicaid patients with schizophrenia, comorbid cardiometabolic conditions are common, and adherence with medications used to treat these conditions is strongly correlated with antipsychotic adherence. Nonadherent patients are at increased risk of use of emergency services and hospitalization. Average one-year costs are higher for adherent compared with nonadherent patients because of medication and outpatient expenditures, but longer-term cost implications of adherence should be explored by future studies.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Dr. Maciejewski is a recipient of Research Career Scientist award RCS 10-391 from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors acknowledge the helpful comments of Christopher Zacker, Ph.D., during the early stages of manuscript preparation.

Dr. Hansen, Dr. Maciejewski, and Dr. Farley have served as consultants to Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Novartis. Dr. Maciejewski owns stock in Amgen. Dr. Farley has received unrestricted grant support from Pfizer and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. At the time of this research, Dr. Yu-Isenberg was with Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation and is now with GlaxoSmithKline.