Despite growth in ambulatory facilities for treatment of mental disorders, hospitals remain a critical treatment component for thousands of people with serious and persistent mental illness. Specialized treatments, such as patient stabilization, complex drug therapy, coordinated psychotherapy, short-term detoxification, intense observation, and crisis care, rely on specialized psychiatric or medical units within community hospitals.

Documented prevalence, incidence, and chronicity of mental illness and addiction have raised awareness of resource availability, use, and cost. Research conducted from 1992 to 1994 in Montgomery County, Maryland, reported that “annually, about 12% of 1600 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services patients with severe mental illness experience 1 or more inpatient care episodes; 90% of these hospitalizations are voluntary” (

1,

2). More recently, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) examined the use of community hospitals for treatment of mental disorders or substance use disorders and found that these diagnoses were responsible for a remarkable proportion of admissions. “In 2004, nearly 1 out of 4 hospital stays for adults in U.S. community-based hospitals involved [mental or substance use disorders]—about 7.6 million hospitalizations. Of these, 1.9 million hospitalizations (6% of adult hospital stays) had a principal [mental or substance use disorder] diagnosis and 5.7 million (18% of adult stays) were primarily for non-[mental or substance use disorders] diagnoses but had a secondary mental health or substance abuse diagnosis” (

3).

According to an AHRQ 2004 analysis, “29% of all days in the hospital, and 22% of total hospital costs were attributable to adults with a [mental or substance use] disorder in 2004.” In addition, “Hospital stays involving [mental or substance use] disorders were 29% longer than stays for [other] conditions (5.8 versus 4.5 days) in 2004. Adults with only a principle [sic] [mental or substance use disorder] diagnosis stayed in the hospital an average of 8 days compared with 5days for patients with no [mental or substance use] condition” (

3). Inpatient care is expensive compared with ambulatory care settings. As Fenton and colleagues (

1) noted, studies of community-based programs for persons with severe mental illness recognize an acute care episode resulting in hospitalization as “the single largest cost element in the array of services needed to provide community care.”

Although patients, communities, insurers, and hospitals face significant economic burdens with inpatient care, quality-of-care guidelines underscore the appropriateness of inpatient care for serious, acute, and complex disorders (

4). Variable insurance coverage, payer limits, and increases in bad debt and charity care compel scrutiny of resources consumed for admissions for a mental or substance use disorder. For various reasons, public and private stakeholders need to understand the costs and potential implications of differences in costs for this category of admissions. Clarity is needed in order for policy makers to design efficient and equitable payment and reimbursement systems. Health insurers and other payers need accurate use and cost estimates to properly budget for mental or substance use disorder treatment utilization. Physicians and other providers need to understand the potential financial implications that a psychiatric hospitalization may have on patients, particularly those who are underinsured or uninsured. Health economists require accurate estimates of costs for economic models used to inform payer and policy maker decisions.

Deinstitutionalization movements resulted in a dramatic decline in the number of psychiatric admissions from the 1960s through the 1990s (

5,

6). Examinations of more recent trends have reported that the rate of deinstitutionalization slowed during the late 1990s (

6) and that the psychiatric admission rate has been flat (

7) or has increased (

5,

8) since 2000. Despite reported increases in psychiatric admissions nationwide, many unanswered questions remain regarding required resources and who carries the burden to pay for psychiatric inpatient services. In contrast to the understanding of care and costs associated with other chronic illnesses (asthma, for example) or with illnesses linked to considerable comorbidity (diabetes, for example), psychiatric disorders and their inpatient treatment are understudied.

Estimating cost of an inpatient day of mental or substance use disorder treatment is not an easy task. From a societal perspective, the meaningful monetary metric is the amount hospitals are reimbursed for providing services. However, discounts that hospitals provide to different payers are considered proprietary and are not publicly available. Hospital charges are often available, but the gap between hospital charges and the amount payers reimburse has grown in reaction to payers' requests for larger discounts (

9). To keep discount rates confidential, data for health care services generally indicate either charges or reimbursed amounts, but not both. A third cost metric is the expense the hospital incurs to provide services. In order to understand cost of psychiatric hospitalization, all threemetrics—cost to deliver care, charges, and reimbursed amounts—are informative and relevant.

Different payers cover different case mixes of patients and have different reimbursement policies within the U.S. health care system. Private payers, who generally cover individuals able to work, often reimburse on the basis of a negotiated discount. In contrast, Medicare eligibility is based on age and disability status and has a prospective payment system that reimburses according to a number of factors, including the diagnosis-related group. A comprehensive view of hospitalization cost in the United States must consider these diagnostic case mixes and payer differences.

The objective of this research was to examine the cost, using a large administrative database, of psychiatric hospitalizations in community hospitals during 2006. The study also examined the relationship between costs and several key variables: length of stay, diagnosis category, and payer type. Finally, costs were characterized in terms to deliver care, charges, and amount reimbursed to hospitals. The amount reimbursed could be obtained only from a second database and therefore provided only an approximate comparison.

Methods

Primary data source

This retrospective analysis examined administrative claims from Premier's Perspective Comparative Database (PPCD), the largest, most detailed U.S. hospital clinical and economic database available and developed for health care quality and utilization benchmarking. The database contains over 2.5 billion patient daily service records, with approximately 45 million records added each month. For this analysis, we selected hospitalizations with a primary psychiatric diagnosis (ICD-9-CM codes 290.00–319.99) and a 2006 discharge date. The result included information for 261,996 psychiatric hospitalizations from 418 unique community hospitals, excluding state-run psychiatric hospitals. In accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, Premier removed personal data identifiers. Because this study used deidentified administrative claims data and did not involve any human intervention or interaction or identifiable private information, it was not submitted for institutional review board approval.

Operational definitions

From detailed PPCD administrative claims data, payers were categorized as Medicare (traditional indemnity, managed-care capitated, and managed-care noncapitated), Medicaid (traditional, managed-care capitated, and managed-care noncapitated), private insurance (managed-care capitated, managed-care noncapitated, commercial indemnity plans, and direct employer contracts), uninsured (self-pay and indigent), and other (worker's compensation, charity, other governmental payers, and other). The primary psychiatric diagnoses for hospitalizations were classified on the basis of ICD-9-CM codes, with “x” indicating any digit, as follows: schizophrenia (295.xx and 298.1x–298.9x), bipolar disorder (296.0x–296.1x and 296.4x–296.9), depression (296.2x–296.3x, 298.0x, 300.4x, 301.12, 309.0x–309.1x, and 311.xx), alcohol use (291.xx, 303.xx, and 305.1x), or drug use (292.xx, 304.xx, and 305.2x–305.9x). Other diagnoses are representative of all other codes between 290.xx and 319.xx.

Statistical methods

The PPCD data did not represent a random sample of U.S. community-based hospitals but did contain a weighting variable based on attributes of available hospitals that allowed for projection of results at the national level. Analyses were done at the hospitalization level rather than at the patient level. If the same patient was hospitalized more than once, each hospitalization was treated as an independent observation. With the number of observations (261,996) and comparisons, results were reported with 95% confidence intervals.

The PPCD contains hospitals' reported costs to deliver care (costs) and charges billed to the payer (charges). The costs variable represents each hospital's estimate of expenses incurred to provide services, including prorated fixed costs of maintaining facilities and variable per-patient care costs. Dowless (

10) overviewed the different methods used by hospitals to calculate these costs. Reimbursed amounts were not included in the PPCD, presumably because of contractual restrictions. These amounts were critical to interpreting results; therefore, primary findings were supplemented with analysis from the MarketScan administrative claims database of reimbursement values.

All analyses were performed with SAS version 9. Means and confidence intervals were calculated using PROC SURVEY means.

MarketScan as supplemental data source

The MarketScan database represents claims submitted to distinct payers, including private or commercial payers and state Medicaid, whereas PPCD represents claims submitted for hospitalizations. The MarketScan database consisted of claims for inpatient care, outpatient care, and outpatient prescription drug use for over 16 million individuals in 2006, from approximately 90 large employers and health plans, and over four million individuals in seven geographically diverse state Medicaid programs.

In the commercial and Medicaid MarketScan databases, we attempted to mirror our analysis from the PPCD: hospitalizations with 2006 discharge dates and the same primary ICD-9-CM diagnoses (290.00–319.99). Diagnoses were then grouped into categories listed previously. Facility claims showing inpatient hospitalization as place of service were used; we excluded from the analysis claims from residential and long-term care facilities and state psychiatric hospitals (which were not included in the PPCD). Total reimbursement included amounts paid to the facility by the insurance company, state, and patient but excluded separate claims for inpatient services by physicians not associated with the facility. Again, analyses were completed at the hospitalization level, rather than at the patient level; however, the MarketScan analyses were not weighted to be nationally representative.

Results

The PPCD contained information on 261,996 unique psychiatric hospitalizations from 418 unique hospitals. Projecting to national levels, in 2006 the estimated total cost for delivering care in U.S. community-based psychiatric hospitalizations was $10.6 billion, with charges of $26.5 billion. The resulting charge-to-cost ratio was 2.5.

The most common primary diagnostic groups were depression (27.8%), schizophrenia (19.5%), bipolar disorder (19.4%), alcohol use disorder (11.6%), and drug use disorder (11.1%), with other psychiatric disorders accounting for the remaining 10.5% of hospitalizations. However, the distribution of diagnostic groups varied by payer type, with schizophrenia (32.7%) being most common for Medicare and depression being most common for Medicaid (24.6%), private payers (35.4%), and the population without insurance (28.6%). Public payers covered over half of the psychiatric hospitalizations (Medicare, 27.2%; Medicaid, 26.0%), with private insurance covering 30.1%. A meaningful portion were uninsured (10.8%), and the remainder (5.8%) were covered by other payers, such as workers' compensation and charity care.

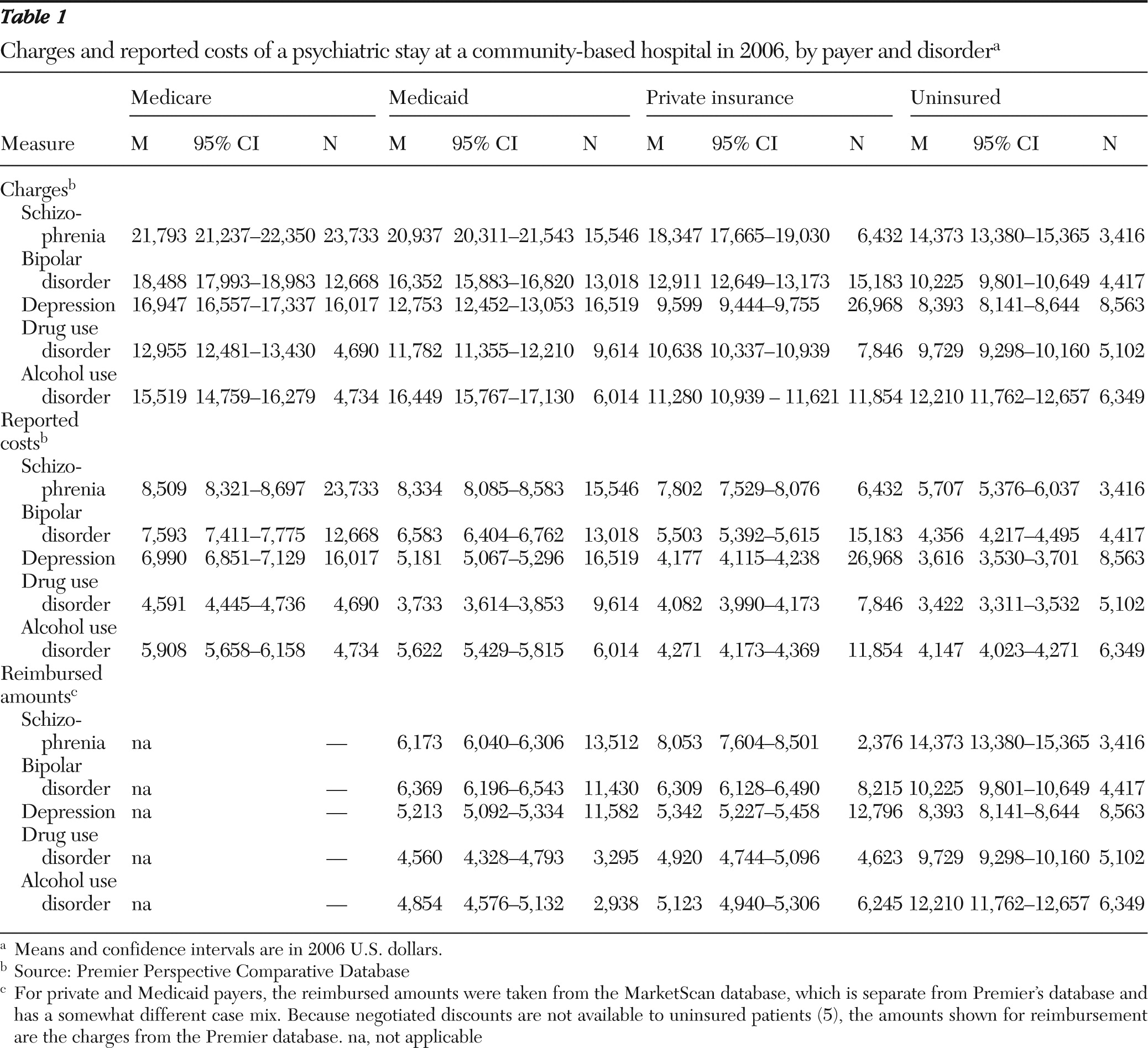

Table 1 shows hospitalization cost by payer type and disorder. In terms of total cost of hospitalizations (mean cost times number of hospitalizations), the most expensive disorder for public payers was schizophrenia, whereas the most expensive disorder for private payers was depression, followed by bipolar disorder. For all payers, the category of other psychiatric disorders was relatively small.

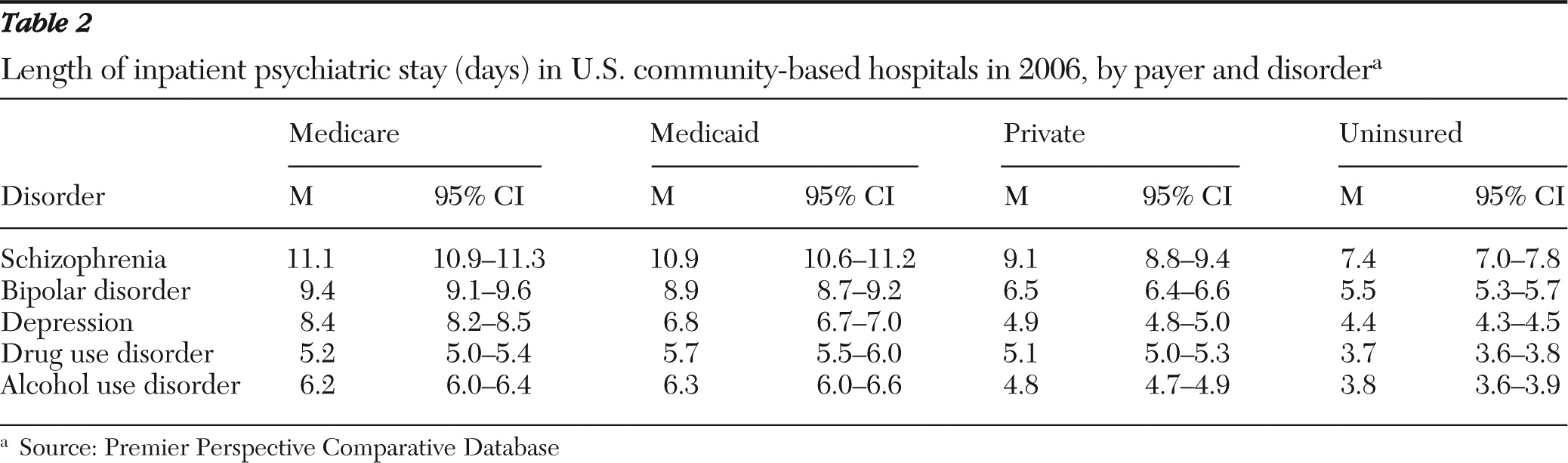

When data for length of stay by payer and disorder were examined (

Table 2), an interesting trend appeared, which varied by disorder. Patients without insurance tended to have the shortest stays, and those with Medicare or Medicaid tended to have the longest. Data on cost to deliver care and charges per hospitalization followed the same ordering as length of stay, suggesting that costs were largely driven by length of stay (

Table 1).

The discrepancy between costs to deliver care and charges (

Table 1) raised questions regarding payers' reimbursements to hospitals. This information was not available in the PPCD, but a contrast with the MarketScan commercial and MarketScan Medicaid data (37,757 and 48,676 hospitalizations, respectively) allowed an approximate comparison with PPCD data concerning observations and length of stay. There were meaningful differences in length of stay in the commercial payer data, with MarketScan generally showing longer average lengths of stay: schizophrenia (9.1 versus 10.4 days), bipolar disorder (6.5 versus 7.2 days), depression (4.9 versus 5.5 days), drug use disorder (5.1 versus 7.7 days), and alcohol use disorder (4.8 versus 6.8 days). Similarly, there were differences in length of stay in the Medicaid data between the PPCD and MarketScan data, respectively: schizophrenia (10.9 versus 10.8 days), bipolar disorder (8.9 versus 10.2 days), depression (6.8 versus 7.1 days), drug use disorder (5.7 versus 8.7 days), and alcohol use disorder (6.3 versus 5.5 days). Despite these differences, the results are informative and indicate that comparisons of reimbursed with charged amounts are confounded by other factors and must be viewed cautiously.

Table 1 also shows reimbursed amounts per hospitalization from the MarketScan data and reported costs to deliver care from the PPCD. For private payers, the estimated amounts reimbursed were consistently slightly higher than costs to deliver care for all disorders. Conversely, state Medicaid reimbursements to hospitals were lower than estimated costs to deliver care for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and alcohol use disorder; they were just slightly more than costs for depression care, and they were higher for drug abuse treatment. The dramatically higher charges for the uninsured from PPCD were included as the amount reimbursed to reflect the absence of negotiated rates.

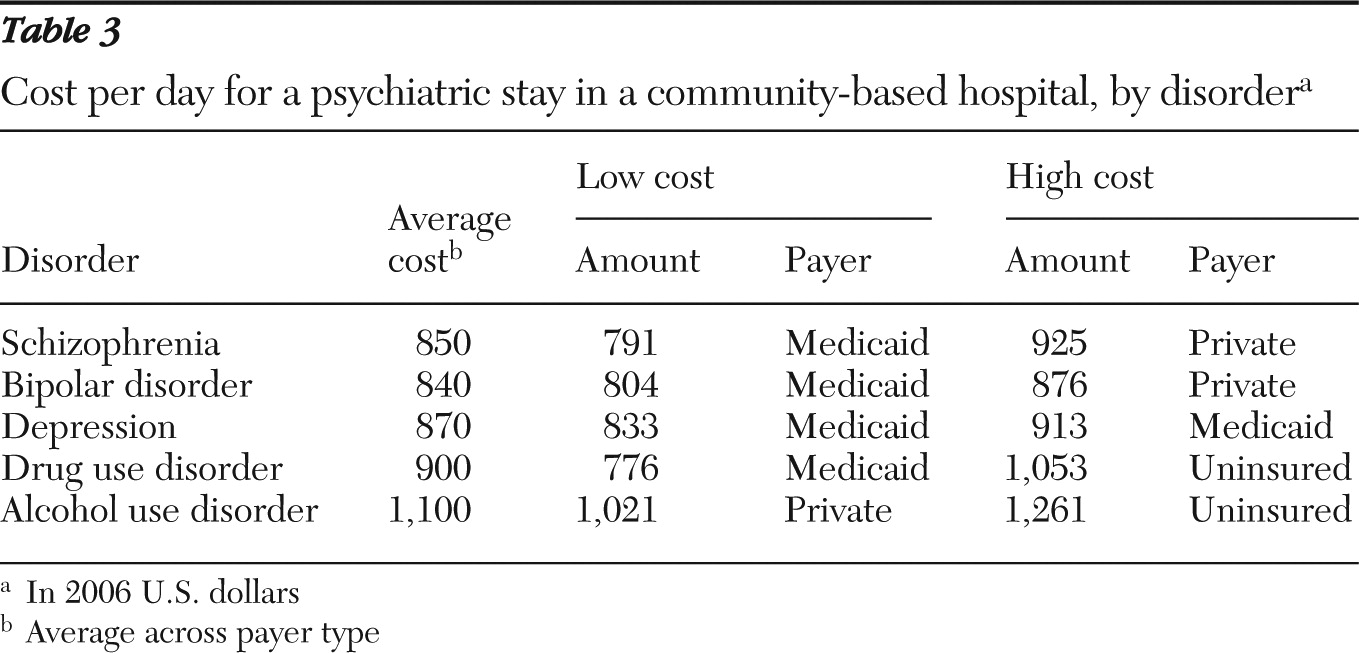

Table 3 gives an overview of costs per day of hospitalization by disorder, including costs for payer type with the lowest and highest costs per day. The disorders with the shorter average length of stay tended to have the highest cost per day, possibly reflecting increased services delivered during the first days of hospitalization.

Discussion

The question of cost incurred for a psychiatric hospitalization in the United States was the impetus for conducting these analyses. A single estimate was difficult to establish because length of stay varied depending on psychiatric disorder and because case mix of psychiatric disorders varied by payer type. These estimates do not include hospital profits and are, therefore, probably lower than the total cost to society.

In addition to daily cost data, an array of other findings emerged from these analyses, including mental or substance use disorder case mix by each major payer category, total costs of hospitalization by disorder, length of stay, and reimbursement rates (from disparate but relevant data) by selected payers. As expected, the case mix across payer types varied significantly. Schizophrenia was the most common diagnosis group for Medicare, and depression was the most common diagnosis group for all other payer types. Not surprisingly, over half of all psychiatric hospitalizations were publicly paid (Medicare and Medicaid), underscoring the debilitating nature of these disorders, which frequently interferes with individuals' ability to maintain employment (

11).

Interestingly, the average cost and charges per hospitalization tended to be commensurate with average length of stay (

Tables 1 and

2). Early research recognized that providers' supply response to payment limits was associated with length of stay and day limits. The response was significantly stronger for psychiatric disorders than for general medical or obstetric conditions (

12). More recent research corroborates these findings, making it difficult to establish the link between disease severity and resources consumed, as measured by costs or charges (

13). In addition, other researchers have highlighted the potential motive for “upcoding” of administrative diagnoses to increase reimbursement rates (

14). It is noteworthy that Medicaid-insured patients incurred the lowest daily costs across four of the five disorders, perhaps emphasizing that publicly paid hospitalizations (Medicaid and Medicare) were significantly longer than those covered by private or uninsured payers. This observation raises a provocative research question about the underlying contributing factors. Does the difference reflect a more severe case mix for publicly funded patients, or is it an outcome of different utilization management underwritten by a private provider? Further research is warranted to better understand these underlying factors.

Analyzing the range of costs across payer types poses the obvious question of why these differences exist, although the answer is far less obvious. A limitation of these data is the ambiguity of how these cost figures are built. The variety of cost-accounting methods used by community hospitals (

10) makes pinpointing the sources of this variance difficult. A consistent trend across cost and charge data is that publicly insured patients incur both higher costs and charges. This finding in psychiatric hospitalizations runs counter to a recent finding with general hospitalizations. A study by the Milliman Group suggested that general hospitalizations involve a cross-subsidization, such that “the total annual cost shift in the United States from Medicare and Medicaid to commercial payers is approximately $88.8 billion” (

15). The study further states that “the hidden nature of this subsidy makes it difficult to quantify and debate.”

The average amount charged per hospitalization was 2.5 times larger than the cost to deliver care. Analysis from the MarketScan database revealed the amount being reimbursed to hospitals by private payers and Medicaid was relatively similar to cost to deliver care. The large discrepancy between charges and other cost metrics highlights the lack of transparency in hospital pricing. Anderson (

9) argued that the gap between reimbursed amounts and charges has arisen as a result of payers negotiating greater discounts while hospitals respond by increasing their charges to offset the discounts negotiated. One of the unintended consequences is highlighted in

Table 3: individuals without health insurance—likely representing those least able to pay—do not have negotiated rates and therefore are charged the full rate.

In the contrasts between reimbursed values and cost to deliver care, the level of reimbursement by Medicaid (the only public payer reimbursement data analyzed in this study) fell short of costs across some types of psychiatric hospitalization. This is particularly disconcerting considering that the analysis did not include charges to the uninsured that result in bad debt for hospitals. Comparatively, the private side had higher reimbursement rates than costs across all types of hospitalization. Under Medicare, this similar disparity resulted in implementation of the prospective payment system, which became effective in January 2006. This system is intended, in part, to close the gap between reimbursement rates and costs, given that this nation faces a rapidly increasing need for psychiatric hospital beds against a decreasing supply (

16). Although cost of psychiatric care has increased substantially over the past 20 years, the highest relative increases have been for outpatient and pharmacological treatment (

17). If reimbursement rates for psychiatric hospitalizations do not cover the cost to deliver care, this treatment option may cease to be available, and a less appropriate setting, such as correctional facilities, may become the alternative “treatment setting” for individuals with severe mental illness (

18,

19).

Although the data sets used for these analyses were robust, a number of study limitations must be acknowledged. First, although cost and charge data were matched from the Premier data set, reimbursement data were extracted from a separate data set (MarketScan); thus reimbursement rates can be used as only approximate comparisons. Cost data did not include direct physician-billed costs (for physicians not on the hospital's payroll) and, therefore, likely understate the total costs associated with a psychiatric hospitalization. Finally, Medicare reimbursement data were not available to compare national rates of reimbursement with state data included in the MarketScan data set; thus no strong conclusions can be drawn about overall public payer reimbursement trends.

Conclusions

This research was successful in estimating psychiatric hospitalization costs for policy makers, payers, and providers. In our examination of three different cost metrics, the hospitals' estimates of cost to deliver care—although an underestimate of true societal cost—appeared to give the most reasonable cost estimate. The idiosyncrasies in the different cost metrics suggest some implications for payers and policy makers. The results were consistent with past research, suggesting that previous attempts to control pricing may have led to unintended consequences, including a large gap between charges and reimbursed amounts, potential cost shifting between payers, and potentially extended lengths of stay to offset reduced per diems. The current reimbursement system in the United States, with its lack of transparency in pricing, makes it challenging to estimate the cost to society for a day of psychiatric hospitalization. Future research is needed to assist policy makers in understanding disparities and cross-subsidization between the public and private sectors, as well as to create better economic incentives to address the diminishing supply of inpatient psychiatric beds across this country.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grant 60660 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and by Eli Lilly and Company.

At the time of the study design and data analysis, Dr. Stensland was a full-time employee of Eli Lilly and Company, which provided funding for this study. Mr. Watson is an employee of and a minor shareholder in Eli Lilly and Company. Dr. Grazier reports no competing interests.