The purpose of this study was to identify a comprehensive set of measures that could be used to address the eight domains identified by the Canadian Institutes of Health Information for service-level evaluation (

10). The domains are acceptability, accessibility, appropriateness, competence, continuity, effectiveness, efficiency, and safety. Performance measures have been defined as “the use of statistical evidence to determine progress towards specific defined organizational objectives” (

11). Process and outcome information can be used to assess quality only when, and to the extent that, they are causally related (

12). Fortunately, there is significant support in the treatment of schizophrenia for a causal relationship between the processes and outcomes measured and the quality of care. Extensive research has demonstrated the effectiveness of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments in schizophrenia (

13–

15).

Methods

The study was undertaken in two stages. First, a systematic literature review was conducted to identify, classify, and organize the measures. Second, a consensus technique was used to prioritize and reduce the number of measures to a core set. The study was approved by the local conjoint health research ethics board.

In the first stage, literature databases—MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, CINAHL, and HealthSTAR—were searched for English language articles on performance measurement published between 1995 and 2004. The following phrases were independently used in the search: performance measure, performance measurement, performance indicator, performance monitoring, quality indicator, quality measure, quality of care, quality of health care, process assessment, outcome assessment, process measure, and outcome measure. In addition, a gray literature search added several online government reports (

16–

19) and reports from professional practice organizations (

20,

21). Citation lists in articles were reviewed for additional sources, and advice was sought from experts in the field to identify additional measures.

Next, the measures were classified and organized by using a performance measure profile template. The characteristics of measures were grouped into three categories: measure content, data required for construction of the measure, and evaluation of the measure. The content of each measure was captured by ten categories: rationale, operational definition of measure, quality domain, numerator statement, numerator data source, denominator statement, denominator data source, type of measure (outcome, process, or proxy outcome), age groups, and data format (that is, reported as simple dichotomous or proportion).

All the identified measures were rated for the level of supporting evidence by a group of four local schizophrenia experts, including an expert in clinical trials, an epidemiologist, and a health services researcher. The levels of evidence ratings were based on criteria used in the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care and modified for use in the Canadian Schizophrenia Practice Guidelines (

20,

22). Strong research-based evidence was rated A. For interventions, examples of an A rating include consistent evidence from well-designed randomized control trials, a meta-analysis in which all the studies included in the statistical pooling were classified as randomized controlled trials, and consistent evidence from well-designed cohort and case studies. For evidence relating to prevalence, consistent findings from appropriately designed studies merited an A rating. Moderate research-based evidence was rated B. This is evidence from study types such as well-designed controlled trials without randomization, cohort studies, case-control analytic studies, comparative studies with historical control, and repeated-measures studies with no control group. The B rating was also used when there were well-designed randomized controlled trials favoring effectiveness but the evidence from such trials was not consistent. Weak or reasonable evidence was rated C. Such evidence was from expert opinions or consensus in the field; descriptive, observational, or qualitative studies (case reports, correlation studies, or secondary analyses); formal reviews; and hypothesis-generating or exploratory studies or subanalyses.

In the second stage, a consensus technique, the Delphi process (

23), was used to obtain stakeholder ratings of the importance of individual measures (with the associated level of evidence, as assessed by the aforementioned group of experts). Historically, two approaches have been used to summarize health information and to resolve inconsistencies in research studies. Statistical methods such as meta-analysis are appropriate when the questions can be addressed with optimal study methods, such as randomized controlled studies, and relevant published data are available. When the data cannot be managed statistically, consensus methods provide another means of synthesizing information, but they are liable to use a wider range of information than is common in statistical methods. When published information is inadequate or nonexistent, these methods provide a means of harnessing the insights of experts to inform decision making (

24).

Several consensus techniques that share the objective of synthesizing judgments when a state of uncertainty exists have been compared. A systematic review of consensus techniques found that the output from such methods may be affected by several factors, such as the way the task is set, the selection of scientific information, the way interaction between members is structured, and the method of synthesizing judgments (

25). The authors' conclusion was that adherence to best practice enhances the validity, reliability, and impact of the product (

25). The Delphi technique was selected for the study reported here because of four key features. First, its anonymity is seen as an advantage when both patients and clinical experts are participating. Second, multiple rounds allow stakeholders to change their opinions in subsequent rounds. Third, feedback between rounds provides the distribution of the group's response along with the individual's previous response. Finally, the Delphi technique does not require stakeholders to meet in person (

26).

The Delphi technique has been previously used in mental health services research, including in the development of a core set of quality measures for mental health and substance-related care (

27), identification of key components of schizophrenia care (

28), development of quality indicators for primary care mental health services (

29), description of service models of community mental health practice (

30), characterization of relapse in schizophrenia (

31), and identification of a set of quality indicators for first-episode psychosis services (

32). Historically, the technique has been used with a panel of experts. The importance of broadening the panel to include clinicians, consumers, and the general public has been emphasized (

33,

34), although some have argued that such a multistakeholder approach is a departure from the well-researched Delphi methodology, which typically uses only experts (

35).

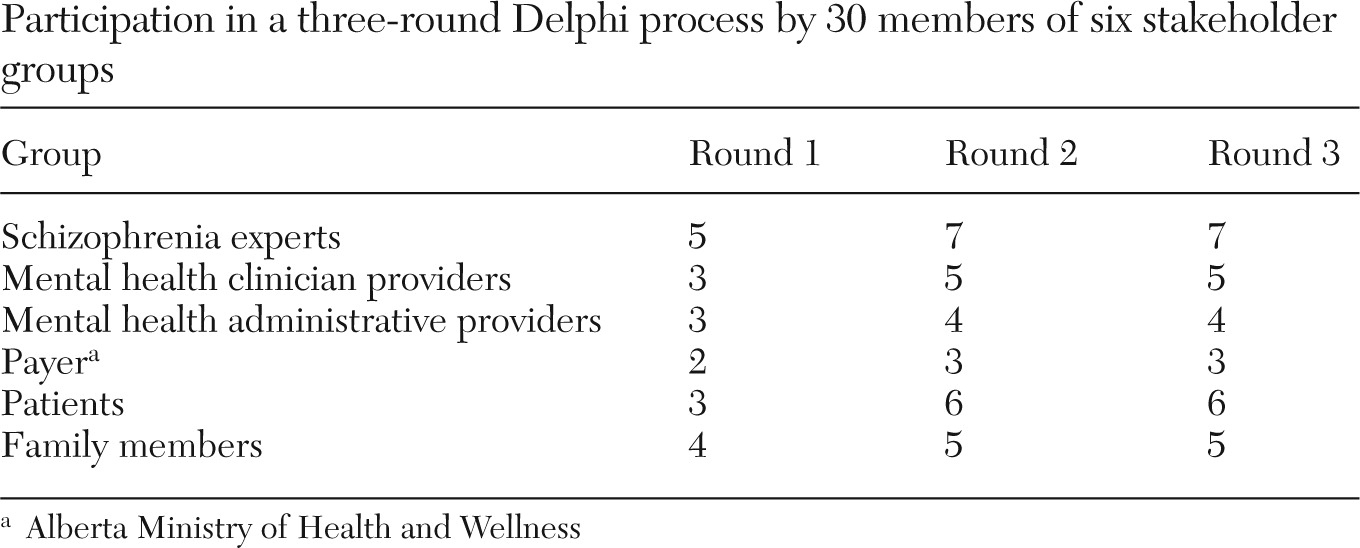

Stakeholders were selected purposefully. Purposive sampling is a nonprobability sampling technique in which participants are not randomly selected. They are deliberately selected to capture a range of specified group characteristics. This form of sampling is based on the assumption that researchers' knowledge of the population can be used to carefully select individuals to be included in the sample (

36). For this study, purposive sampling was superior to the alternatives because the stakeholders were selected on the basis of their breadth of experience and knowledge, as well as their willingness and ability to articulate their opinions. Optimal sample size in research using the Delphi technique has not been established, and there is scant empirical evidence on the effect of the number of stakeholders on either the reliability or validity of consensus processes (

37). Research has been published based on samples varying from between ten and 50 to much larger numbers (

38). We identified 30 stakeholders for participation in the Delphi. The stakeholders were from six groups: schizophrenia experts, mental health clinician providers, mental health administrative providers, the payer, patients, and family members.

At the proposal-writing stage, the first author contacted government representatives from the Alberta Ministry of Health and Wellness (the payer) and administrative representatives from the provider organization to explain the project and details of participation. The agency that funded health services research required that a decision maker be involved in research proposal development as well as project completion in order to support knowledge translation. Potential family and patient participants were identified by staff members (interested clinicians) of a specialized schizophrenia service.

The Delphi questionnaire was developed from the list of performance measures from the systematic review and pilot-tested with local clinicians, patients, and service managers. Pilot testing involved individual, in-person administration of the questionnaire by the study coordinator to stakeholder group representatives. The questionnaire was examined for clarity of the instructions, definitions, and descriptions of the performance measures and for reading level. The Delphi questionnaire was administered in person by the study coordinator to each individual in the patient stakeholder group. All other stakeholders received a written questionnaire, either by e-mail or by post if they did not have computer access. The stakeholders were provided information from the first stage of the research—the systematic review and ratings of supportive evidence.

The Delphi comprised three rounds that occurred between June and November 2005. The first round was an open round in which the stakeholders were invited to provide comments about the indicators. Each round of questionnaires included a qualitative component that offered the opportunity to provide additional feedback in the form of written comments, and each round built upon responses in the former round.

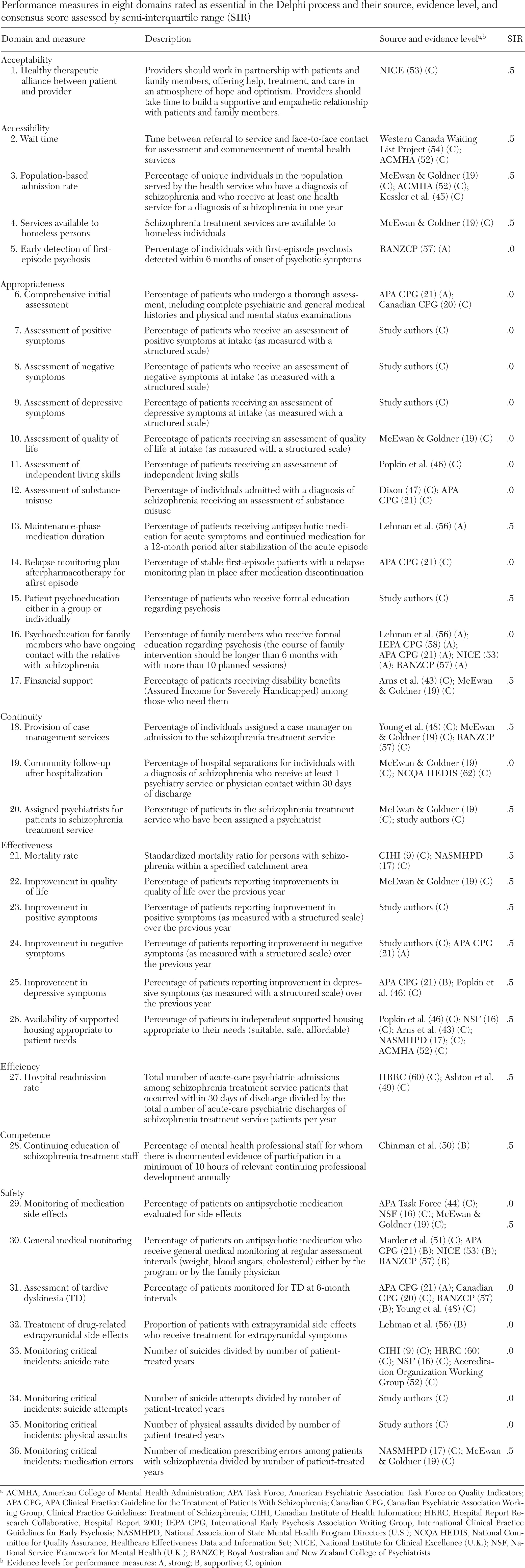

In rounds 2 and 3, the stakeholders were asked to rate the importance of the individual measures on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 to 5 (1, essential; 2, very important; 3, important; 4, less important; and 5, unimportant). After each round, stakeholders were provided with feedback and a summary of the previous round. The feedback to each participant included the participant's rating of the importance of each performance measure, along with the group's median rating, the percentage of participants with ratings at each point on the Likert scale, and a synopsis of written comments. Participants were then asked to reflect upon the feedback and rate each item again in light of the new information. In the event that their response was more than 2 points away from the group median, they were asked to elaborate with comments.

The degree of consensus achieved in the Delphi was assessed by calculating the semi-interquartile range for each measure after each round. The semi-interquartile range is calculated from the following formula:

The level of consensus was set before data collection began. Consensus was defined as measures for which the final ratings had a semi-interquartile range of ≤.5. Measures with final ratings with a semi-interquartile range of ≤.5 were interpreted as being essential (

30). Ratings were analyzed (medians, means, and semi-interquartile ranges) with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (

39).

Discussion

This study used a three-step process to identify and select performance measures deemed essential for the evaluation of schizophrenia services. Each step, from the systematic review to the rating of supportive evidence and the selection of indicators, used a rigorous methodology. The result is a list of 36 measures that encompass the eight performance domains recommended for program evaluation. This list provides a useful starting point for further work to develop operational definitions and data sources for performance measure implementation. The list of measures is more detailed than measures in widely implemented general health system indicator lists, such as the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) (

61), which have been found to have a narrow focus and limited application to many components of mental health services (

62). The National Committee for Quality Assurance, the developer of HEDIS, is in the process of developing a set of schizophrenia measures for state Medicaid programs and U.S. health plans.

The literature review identified 97 performance measures, and the Delphi technique successfully narrowed the list to 36 measures that were identified as essential by a multistakeholder group. The stakeholder consensus process thus established the face validity of these performance measures (

63). Several of the measures can be considered evidence based, which is defined as measures supported by clinical trial data that links the process measured to improved outcomes. Examples of evidence-based measures include maintenance antipsychotic medication and family and patient psychoeducation (

63–

65). Only seven outcome measures were identified as essential, and hospitalization rate is the only one in this group that is reliably measured and readily available. It is one of only three mental health performance measures available at a federal level in Canada (

9). Hospitalization has been suggested as a good proxy outcome measure for schizophrenia research (

30), and its application has been extended in first-episode psychosis by development of a robust risk adjustment model that facilitates the comparison of real-life services (

66). Although relapse rates were identified as essential in the Delphi process, in practice these are difficult to measure, and hospitalization has often been used as a more concrete and easily measured proxy for relapse (

67).

This study had several limitations. First, the measures rated were based on a literature search up to July 2004. The delay in completing the project and publication was the result of personnel issues. One purpose of using a Delphi process in this study was to reduce the number of items. Although the reduction from 97 to 36 was useful, 36 measures represent a larger group than would be practical in standard program evaluation. There is some redundancy within the list in that there are four items for assessing symptoms and quality of life (in the appropriateness domain) and another four for the percentage of patients showing an improvement in those measures over the course of one year (in the effectiveness domain). In addition, we did not examine differences between the various groups of Delphi participants. Although this might prove interesting, the study was not designed to use the process in this way. We selected a Delphi group that would be large enough to undertake the planned task, but it was not large enough to undertake a secondary analysis involving comparison of the subgroups independently. Programs that plan to use the measures can further reduce the number of measures by carefully examining the cost and feasibility and applicability of the measures in their situation. Mortality rate is an example of a performance measure for which the necessary data are not usually readily available at a program level. Calculation of this rate would require large-scale population-based information.