Anticonvulsant use for psychiatric conditions of children and adolescents has expanded considerably in the United States in the past 25 years. Over the period from 1987 to 1996, trend analyses for dispensed medications to treat emotional and behavioral disorders of youths revealed that anticonvulsant mood stabilizers increased 5.9 fold and 2.2 fold in two state Medicaid populations and 2.5 fold in a population insured through a health maintenance organization (HMO) (

1). Likewise, in a household survey of U.S. parents who were queried about their children’s medical care, the prevalence of use of anticonvulsants, lithium, or both for mood stabilization increased more than threefold from 1987 to 1996 (

2). A regional ten-year study of psychotropic prescribing trends similarly showed a twofold increase in the use of anticonvulsant mood stabilizers among HMO-insured youths ages five to 17 years over the period of 1994–2003 (

3). This trend from 1987 through 2003 was consistent across studies, although the prevalence of use of these anticonvulsants was greater for those insured via Medicaid than through private insurance (

1,

3).

The temporal increase in prevalence of using anticonvulsants as a mood stabilizer among youths, however, did not differentiate trends in the proportional use of anticonvulsants as mood stabilizers versus their use for seizure disorders. In a 1992 study of continuously enrolled Tennessee Medicaid youths from birth to age 18 years who were new recipients of an anticonvulsant, 60% had a diagnosis of a seizure disorder, whereas 11% had a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder (

4). However, in a year 2000 mid-Atlantic Medicaid study of 4,522 continuously enrolled youths under age 18, 81% of those who were dispensed anticonvulsants had a psychiatric diagnosis and only 19% had a seizure diagnosis (

5).

More recent data on anticonvulsant mood stabilizer use among youths are needed to clarify and update these trends. Consequently, we examined national prevalence trends of anticonvulsants for psychiatric indications in outpatient medical visits of children and adolescents over four periods between 1996 and 2009. These data extracts of physician office visits, which included the recording of prescribed anticonvulsant medications, were additionally assessed in terms of demographic and clinical drug treatment patterns and in relation to patient diagnoses. Additional data can shed light on psychiatric practice patterns involving use of anticonvulsants in view of boxed warnings from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), pediatric clinical trial findings showing low effect size when using anticonvulsants to treat psychiatric disorders (

6), and safety concerns about off-label uses, particularly for newer products, such as lamotrigine.

Methods

Data source and survey design

Data were derived from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS). These surveys are conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The NAMCS is a nationally representative sample of visits to nonfederally employed office-based physicians who are primarily engaged in direct patient care. The NHAMCS is a nationally representative sample of visits to the emergency departments and outpatient departments of noninstitutional general and short-stay hospitals, exclusive of federal, military, and Veterans Affairs medical centers.

Both surveys have a similar structure. The NAMCS uses a multistage probability design, which includes samples from primary sampling units (a county, a group of adjacent counties, or a standard metropolitan statistical area), from physician practices according to specialty within these units, and from patient visits within these practices. The NHAMCS uses patient visits in hospitals within primary sampling units, in clinic outpatient departments, in emergency service areas within these hospitals, and in patient visits to these clinics. Data from a systematic random sample of patient visits from each physician practice are assessed. These data include patients’ demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics. Following NCHS guidelines, we combined NAMCS and NHAMCS medical visit data from contiguous survey years to arrive at stable estimates.

Medical visits were grouped into time periods as follows: 1996–1997, 2000–2001, 2004–2005, and 2008–2009. Across the recorded years, survey response rates varied between 59% and 97%, with a median response rate of 85.4%. Each visit was assigned a value, the sum of which projected to an estimate of the total medical visits nationally. This value is referred to as the weighted value estimate and is a complex estimate based on three factors, as determined by the NCHS. Alongside these estimates, we included the actual recorded number of unweighted visits.

Demographic characteristics

Demographic data included patient age group (birth through age 13 years and ages 14 through 17 years), gender, and race-ethnicity. Race-ethnicity was divided into six categories: white, non-Hispanic; black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; Asian; other race-ethnicity (Native American, Pacific Islander, or more than one race); and blank (respondent did not disclose).

Medications

Drug data were coded with the Ambulatory Care Drug Database System, a unique classification scheme developed at NCHS, where drugs are listed by entry name (the name used by the respondent to record the drug). In this study, anticonvulsant mood stabilizer drugs (when recorded as entities) were identified by their generic name. Psychotropic drug use was classified by therapeutic class, as represented in the

National Drug Code Directory in survey years before 2006 and by the Cerner Multum, Inc., Lexicon Drug Database (

7) for 2006 and later. Although the Multum database recognizes up to three therapeutic drug classes for each drug, our analysis considered the first, or primary, therapeutic indication to identify psychiatric drug use.

For survey years up to 2001, up to six medications were allowed to be recorded per medical visit, whereas in survey years 2002 and later, up to eight recorded medications were allowed. Medical visits in which anticonvulsants were prescribed for psychiatric indications included the generic code for divalproex, carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate. Valproic acid and derivatives (sodium valproate and divalproex sodium) were represented under divalproex.

Visits with concomitant psychotropic medication use included any of the following drug classes: stimulants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and other psychotropic drugs (anxiolytics, hypnotics, alpha-agonists, and lithium). For each anticonvulsant mood stabilizer visit associated with concomitant psychotropic use, the specific psychotropic class or classes were identified. The number of additional psychotropic drug classes was also analyzed and categorized into three groups: anticonvulsant alone, anticonvulsant plus one psychotropic class, and anticonvulsant plus two or more psychotropic classes.

Diagnoses

Diagnoses were recorded by physicians according to ICD-9-CM codes. We identified psychiatric diagnoses by ICD-9-CM codes 290.xx–319.xx and seizure and convulsive diagnoses by codes 345.xx and 780.3. Included as psychiatric diagnoses were codes 314–314.99 for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); 312.00–312.49 and 312.80–312.99 for conduct disorder; 313.81 for oppositional defiant disorder; 296.00–296.19, 296.4–296.82, 296.89, 296.90, and 301.13 for bipolar disorder; and 296.2–296.3, 300.4, 311, 300–300.3, 300.5–300.9, 308.3, and 309.81 for depression and anxiety disorders. All other ICD-9-CM codes between 290 and 319 excluding the above-mentioned categories were labeled as “other psychiatric disorder.”

Up to three diagnoses could be recorded for each visit that noted use of an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer, and they were grouped accordingly into four mutually exclusive diagnostic categories: visits with a psychiatric diagnosis and no seizure diagnosis, visits with a seizure diagnosis and no psychiatric diagnosis, visits with both a psychiatric and a seizure diagnosis, and visits with neither a psychiatric nor a seizure diagnosis.

Analytic strategy

The primary independent variable was grouped study years, with demographic variables (gender, age group, and race-ethnicity) as covariates. The primary dependent variable (outcome) was the percentage of visits that noted both an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer and a psychiatric diagnosis, presented as a proportion of all youth visits that noted an anticonvulsant mood stabilizer. Total, diagnosis-stratified, and specific drug visits, as well as visits involving concomitant use of anticonvulsant and other psychotropic medications were analyzed and presented as a percentage of visits noting an anticonvulsant and a psychiatric diagnosis.

Chi square analyses were used to compare data between grouped years 1996–1997 and 2008–2009 to identify statistically significant temporal changes. All data analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2.

Discussion

The major finding of this study concerns the growth of anticonvulsant use for children and adolescents with a psychiatric diagnosis, particularly for a behavioral disorder. This growth continues despite clinical trial findings that challenge the efficacy (

6) and safety of this class of drugs for this population (

8–

10). Concomitant anticonvulsant mood stabilizer use with psychotropic drug classes, particularly stimulants, underscores complex drug regimens that require monitoring for safety and benefits.

Labeled indications and off-label use

The introduction and marketing in the 1990s of numerous anticonvulsant drugs such as lamotrigine for psychiatric indications clearly contributed to their frequency of use. Anticonvulsant drugs have been used for psychiatric and neurologic disorders other than those considered in this study. For adults, for example, divalproex has an indication for migraine and for manic episodes, and gabapentin is indicated for neuralgia (

11,

12). Furthermore, many anticonvulsant drugs are used off label for psychiatric conditions. Examples include topiramate for treating eating disorders and topiramate plus carbamazepine for treating alcohol withdrawal (

13,

14). Topiramate, gabapentin, and oxcarbazepine do not have approved indications for any psychiatric condition in either the adult or the pediatric population.

The decline of divalproex and the rise of lamotrigine

Divalproex was the primary anticonvulsant used to treat psychiatric disorders among youths in the 1990s. However, this drug has been used off label to treat behavior disorders (such as ADHD) among youths. Since the mid-2000s, its proportional use has prominently decreased (

Table 3). In part, this decline may be due to evidence that divalproex has no benefit in the treatment of early-onset bipolar disorder (

6) and to clinical trial data showing that use of the drug has a low effect size among youths (

8–

10). The practice standards of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry acknowledge that “most of the treatment recommendations for pediatric bipolar disorder are derived from the adult literature for acute mania” (

15) but surprisingly recommend anticonvulsants or antipsychotics or a combination as primary treatment for that disorder (

15).

Evidence supporting serious safety concerns for divalproex has emerged in the past two decades, including FDA boxed warnings for both hepatotoxicity and pancreatitis among younger patients (

16,

17) and teratogenicity among females of childbearing age (

18,

19). The marked proportional decline in the use of divalproex among youths to treat psychiatric disorders has been a major factor in the overall moderate decline in anticonvulsant mood stabilizer prevalence in the late 2000s, as shown in this study. The increased use of lamotrigine among youths for psychiatric indications in the past decade is notable. Lamotrigine received an FDA indication for the maintenance treatment of bipolar depression among adults (

20), which may have led to its increased use by children with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Lamotrigine also carries the risk of a potentially life-threatening rash, which can affect patients of any age, but particularly youths. This risk is increased when lamotrigine is used concomitantly with divalproex (

21,

22).

Concomitant psychotropic use

Anticonvulsant medication concomitantly used with other psychotropic medication classes for the treatment of psychiatric disorders was common in 1996–1997 (76.7%) and was even more common by 2008–2009 (87.6%). Furthermore, the use of two or more psychotropic classes with anticonvulsants has prominently increased in the late 2000s, more than tripling from 14.0% to 47.4%. Such use of anticonvulsant medications is off label and primarily for treating behavior disorders and pediatric bipolar disorder, as shown in

Table 3 for 2008–2009. Studies of the addition of divalproex to antipsychotic medications among youths indicate that these combinations lead to marginal increases in behavioral control while increasing side effects such as weight gain and metabolic abnormalities (

23,

24).

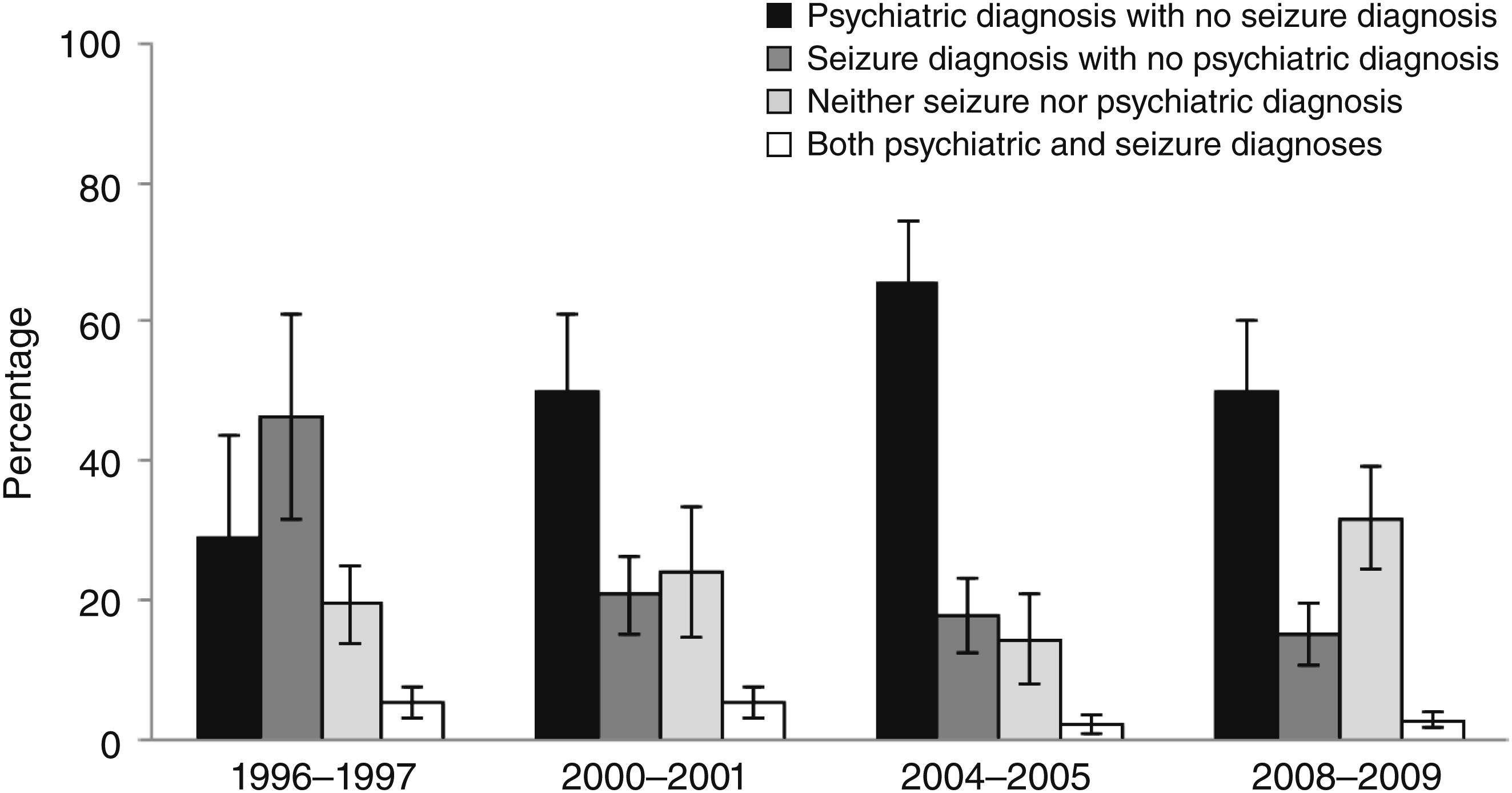

Seizure frequency from 1996–1997 to 2008–2009

Additional data were generated to measure trends in anticonvulsant mood stabilizer use as a proportion of visits for anticonvulsants among four diagnostic groups (

Figure 1), as a proportion of all youth visits (

Table 2), and as a proportion of mental health diagnostic group visits (

Table 3). The proportional decline in use of anticonvulsants to treat seizures compared with all anticonvulsant mood stabilizer visits (

Figure 1) is misleading. This is clear from the data in

Table 1, which presents visits for seizures as a proportion of all youth visits. In that analysis, there was no decline in seizure prevalence over the 14-year period of the study. When visits for anticonvulsant mood stabilizers were measured as a proportion of visits for seizures, the change across the years was not significant. A part of the confusion is that only six of the ten leading anticonvulsant medications used for the treatment of seizures included in this study are mood stabilizer medications (

25). Nonetheless, the stable rate of visits for seizures during these study years is consistent with the findings from other surveys during the same period (

26).

Limitations

A major problem of this study relates to the statistical power of the NAMCS and NHAMCS survey data. Thus, because of small samples, we were unable to examine data for very young children and to characterize this age group by diagnosis. In addition, these surveys measure prescribing practices, and therefore it is not known whether the patients filled their prescriptions and consumed these medications. In addition, the sample was restricted to ambulatory visits, which precluded identification of inpatient anticonvulsant mood stabilizer utilization patterns. Finally, clinician reports of psychiatric diagnoses do not have the reliability typical of clinical research studies.

Conclusions

With national survey data, we corroborated earlier regional Medicaid findings regarding use of anticonvulsants for psychiatric conditions across 14 years. Anticonvulsant mood stabilizer use for seizure disorders among youths has remained relatively stable during these years. Anticonvulsant use for psychiatric disorders peaked in 2004–2005. Over the study period, specific drug entity changes included decreased use of divalproex and increased use of lamotrigine.

Even though our data show a moderate decrease in anticonvulsant use for psychiatric disorders between 2004–2005 and 2008–2009, there was a growing trend for concomitant psychotropic regimens involving anticonvulsants. This trend was especially significant in the off-label treatment of disruptive disorders among youths (p<.001). Clinical review and monitoring can be mandated by policy makers in Medicaid and private insurance programs to ensure appropriate use of these complex regimens.