Reports of significantly increased mortality among individuals with serious mental illness have raised concerns about their general medical health (

1). Although the higher mortality is to some extent explained by the greater prevalence of comorbid general medical conditions and lifestyle factors, it may be at least partly attributable to disparities in receipt of medical care (

2,

3). Individuals with serious mental illness are less likely than their peers without mental disorders to receive various general medical services (

4). There are also reports of significant delays in receipt of medical care among these individuals (

2). With few exceptions (

2,

5,

6), studies have rarely explored reasons for delays in medical care seeking in this population. A 2000 study in Maryland found a substantially greater prevalence of such delays among individuals with serious mental illness compared with a general population sample because of greater difficulty accessing services, excessively long wait time, or transportation difficulties (

5).

In this study, we assessed delays in seeking general medical care in a more recent sample of individuals with serious mental illness, compared with a general population sample. We also examined sociodemographic and clinical correlates of delays among individuals with serious mental illness and association of delays with current health status and use of emergency services. We hypothesized that individuals with serious mental illness experience longer delays than individuals in the general population and that these delays are associated with more severe psychiatric symptoms and poorer functioning. We also hypothesized that participants with serious mental illness who delay medical care seeking are more likely to report poor health and the use of emergency medical services.

Methods

The sample of participants with serious mental illness (clinic sample) was drawn from consecutive admissions (August 2008 to December 2012) to two urban outpatient psychiatric clinics in Baltimore. Adults with DSM-IV clinical diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, bipolar disorder (type I or II), delusional disorder, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, or major depressive disorder (severe with psychotic features) were included. A total of 874 patients were approached, of whom 271 (31%) agreed to participate and completed the assessment. All participants provided written consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The comparison sample was drawn from public-access data for adult participants in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). To help ensure similarity to the clinic sample, the NHIS sample was limited to 40,016 of the 109,683 NHIS participants in 2008–2011 (response rate 74%−82%) who resided in the South census region (which includes Maryland). In further analyses, we compared the clinic sample with 2,723 NHIS participants who reported having seen or talked to a mental health professional in the past year.

Delays in seeking general medical care in the past 12 months were assessed by seven questions. Five were drawn from the NHIS interview. Participants were asked whether they delayed care seeking because they could not get through on the telephone, could not get an appointment soon enough, had to wait too long to see the doctor once they arrived, the clinic or doctor’s office was not open when they could get there, or they did not have transportation. Two additional questions were asked only of the clinic sample: whether they delayed medical visits because they did not have health insurance or could not afford care, or whether they were concerned that they would be treated differently because of their mental illness. Participants could report more than one reason.

Self-rated general health status was based on a scale from excellent to poor. Participants were also asked whether they had ever been diagnosed by a health professional as having angina pectoris, heart attack, any heart disease, stroke, hypertension, emphysema, cancer, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes. Each condition was assessed with a separate question. Participants were also asked about a diagnosis of weak or failing kidneys in the past 12 months.

The clinic sample was asked about visits to an emergency department for any reasons in the past year and then about visits specifically for physical health problems. Participants were asked the reason for the visit. Routine care setting was assessed in the clinic sample by asking where they usually went when they needed “routine or preventive care.” Psychiatric diagnoses for the clinic sample were extracted from medical records and were based on 60- to 90-minute clinical interviews by experienced attending psychiatrists. No psychiatric diagnoses were available for the NHIS sample.

Severity of mental illness symptoms was assessed in the clinic sample with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (

7), which is based on a structured interview, and the Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-24) (

8). Clinic participants were questioned about activities of daily living and how often they received help for a range of activities, including “making it to your doctors or health appointments.” Serious cognitive deficit was also assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination (

9). Sex, age, race-ethnicity, education, and current employment and disability status were recorded for both samples.

Analyses were conducted in three stages. First, prevalence of delays in care seeking for various reasons was compared between samples by using unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses. Adjusted analyses controlled for sex, age, race-ethnicity, education, health status, and chronic health conditions. Second, associations of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics with delays were assessed in the clinic sample by unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses. Adjusted analyses were conducted with multiple imputation for missing data with ten imputed data sets (

10). In the third stage, we assessed the association of any reported delays in the clinic sample with self-rated health status and use of emergency department services for medical reasons using adjusted logistic regression models, which controlled for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics that were associated (p≤.2) with both delays and self-rated health status or the use of emergency services. All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 12.

Results

Most of the 271 clinic participants were female (N=144, 53%), and disabled (N=169, 62%) and had at least a high school education (N=183, 67%). The mean±SD age of the clinic participants was 42±11. Most (N=147, 54%) were non-Hispanic black, 91 (34%) were non-Hispanic white, two (1%) were Hispanic and 31 (11%) were from other racial-ethnic groups. Seventy-one percent (N=192) reported at least one of the general medical conditions assessed. Approximately one-third (N=89, 33%) had a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorders; whereas, 163 (60%) had a mood disorder diagnosis. Most of the 40,016 NHIS participants were also female (N=22,488, 56%) and had at least a high school education (N=33,429, 60%). However, most were non-Hispanic white (N=21,466, 54%), with non-Hispanic blacks (N=9,505, 24%), Hispanics (N=7,173, 18%), and other racial-ethnic groups (N=51,858, 5%) accounting for the rest (race and ethnicity data were missing for 14 participants). The mean age was 48±18. A total of 18,670 (47%) reported at least one general medical condition.

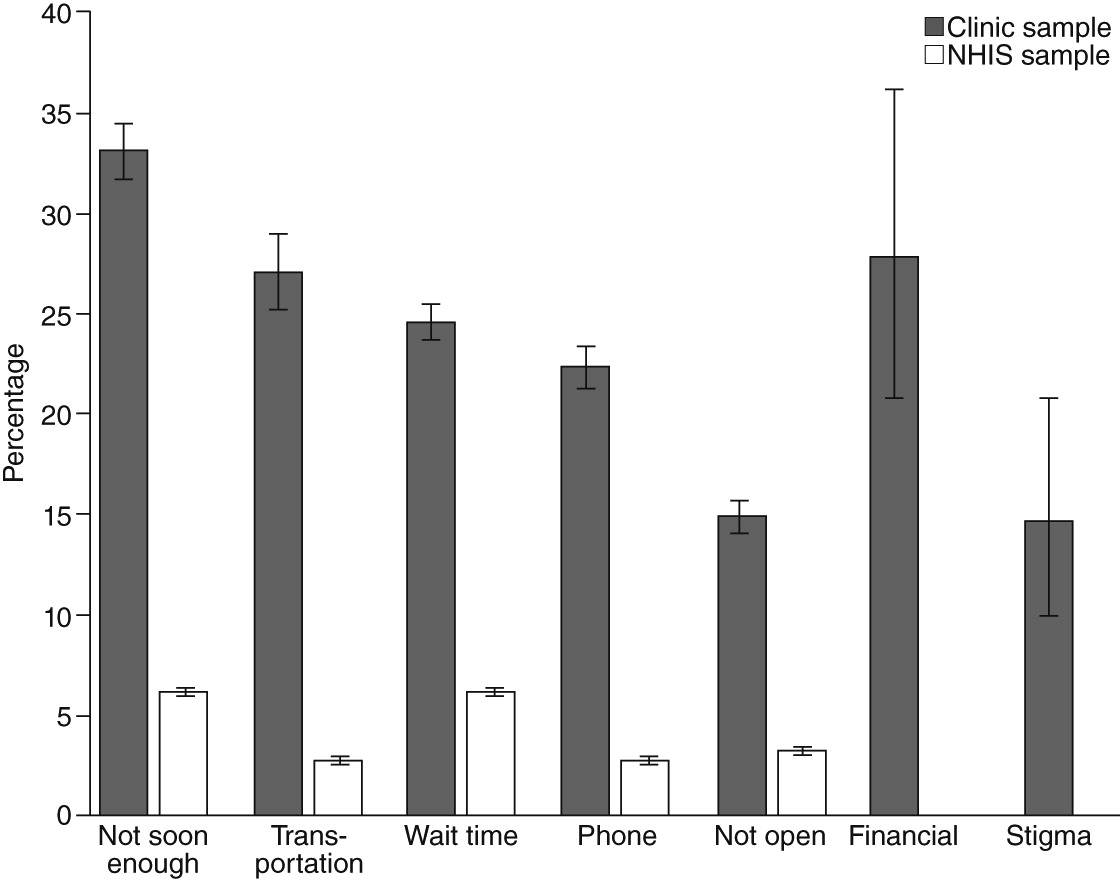

In both the unadjusted and adjusted comparisons, clinic participants were more likely than NHIS participants to report delays in medical care seeking for any reason (

Figure 1). Reasons included not being given an appointment soon enough (33% versus 6%, adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=4.53, 95% confidence interval [CI]=3.44–5.97), not having transportation (27% versus 3%, AOR=3.28, CI=2.42–4.45), too long a wait after arriving (25% versus 6%, AOR=2.72, CI=2.03–3.66), not being able to reach the service by phone (22% versus 3%, AOR=6.07, CI=4.42–8.35), and the service not being open at a convenient time (15% versus 3%, AOR=3.06, CI=2.13–4.39, p<.001 for all tests). Fifty-three percent of clinic participants reported delays for at least one of these reasons, compared with 13% of NHIS participants (AOR=4.01, CI=3.11–5.16; p<.001). Furthermore, 35% of clinic participants and 5% of the NHIS sample reported more than one reason. Results were similar when the NHIS sample was limited to 2,723 participants who reported having had mental health contacts in the past year. In addition, 28% of clinic participants reported delays because they did not have insurance or could not afford care and 15% because of concerns about being treated differently because of their mental illness.

Delays were associated with few demographic or health characteristics in the clinic sample. In adjusted analyses, individuals in the “other” racial-ethnic group (including both Hispanic and other non-Hispanic groups) were less likely to report a delay, whereas those receiving care in a public clinic or health center were more likely, compared with those receiving care at a doctor’s office or health maintenance organization. Participants with higher scores on the depression and functioning difficulties scale of BASIS-24 were more likely to report delays. [A table included in an online

data supplement summarizes data from these analyses.]

Fifty-eight percent of clinic participants who reported delays rated their health as poor or fair and 15% as excellent or very good, compared with 46% and 26%, respectively, among those who did not report delays. These differences were statistically significant in the adjusted model controlling for race-ethnicity (AOR=1.65, CI=1.03–2.65, p=.039). Race-ethnicity was included in the model because it was associated with both delays in care seeking and health status at p≤.2.

Seventy percent of clinic participants who reported delays reported emergency department use, compared with 48% of those who did not report delays. The difference was statistically significant in the adjusted model controlling for sex (AOR=2.39, CI=1.42–4.03, p=.001). Sex was included in the model because it was associated with both delay in care seeking and emergency department use at p≤.2. The most common reasons for emergency visits were unspecified pain, acute injuries, chest pain, and shortness of breath.

Discussion

This study found that individuals with serious mental illness were more likely than the general population members to report delays in seeking general medical care. Indeed, most individuals with serious mental illness reported such delays. These findings are consistent with previous findings of delays and disparities in medical care seeking among individuals with serious mental illness (

2–

6).

This study also found that many delays were attributed to structural barriers, such as difficulty reaching services and getting an appointment, long wait times, not having transportation, and affordability. This finding suggests that if these services are made more accessible, individuals with serious mental illness, like other marginalized population groups, will benefit from them. Consistent with this view, the setting in which the clinic participants received routine medical care was the strongest predictor of such delays.

The association of delays with depressive symptoms and self-reported functioning difficulties points to the role of common disabilities experienced by many individuals with serious mental illness. Assessment of these disabilities may help target appropriate support services to patients who are most in need and who would most benefit from such interventions. Some simple and cost-effective interventions have been shown to remediate cognitive difficulties and improve self-management of day-to-day activities (

11,

12). These interventions and targeted case-management support (

13) may also improve patients’ ability to access medical services.

Delays in seeking general medical care were associated with poorer general health status and increased emergency department use for general medical conditions. Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, it was not possible to establish a causal relationship between delays and these outcomes. Although we tested for a possible confounding effect of the number of medical conditions, age, and other demographic characteristics, these findings should be explored in longitudinal studies.

The self-report nature of the data and the lack of information about length of delays and specific care settings in which participants experienced delays are other limitations. Also, unmeasured differences between the samples may explain some of the differences in reasons for delays.

Conclusions

The findings highlight common delays in seeking general medical care among individuals with serious mental illness in urban psychiatric settings. Integration of mental health and general medical services as envisioned in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) may ameliorate some access problems (

14). Indeed, research has shown that integration can improve access to general medical care and outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness (

15). As the ACA is implemented, it is important to continue monitoring access to medical care and outcomes in this vulnerable group of patients.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was partly supported by the Center for Mental Health Initiatives at the Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Dr. Mojtabai has received consulting fees from Lundbeck. The other authors report no competing interests.