Depression is a common mental disease worldwide, affecting more than 350 million people of all ages (

1). Suicide, related to this disorder, is a top ten cause of death in the eight regions of the world with the most advanced health transition (

2). The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that neuropsychiatric disorders contribute to 13% of the global burden of disease and has projected that this percentage will rise to 14.7% by 2020 (

3). Clearly, depression represents a relevant public health issue worldwide, given the remarkable diffusion of this illness in the population and the possible consequences in terms of disability (

4).

An Italian study involving 4,712 persons reported that between 2001 and 2003, a lifetime mental disorder was experienced by one in five persons, a mental disorder in the prior year by one in 14 persons, and a mental disorder in the prior month by one in 31 persons. In addition, the risk of any mental illness was reported to be almost three times higher among women than men (

6). Consequently, the consumption of neuropsychiatric drugs, such as antidepressant medication, is expected to increase in Italy, consistent with trends reported worldwide in the past decade (

7–

11).

Results

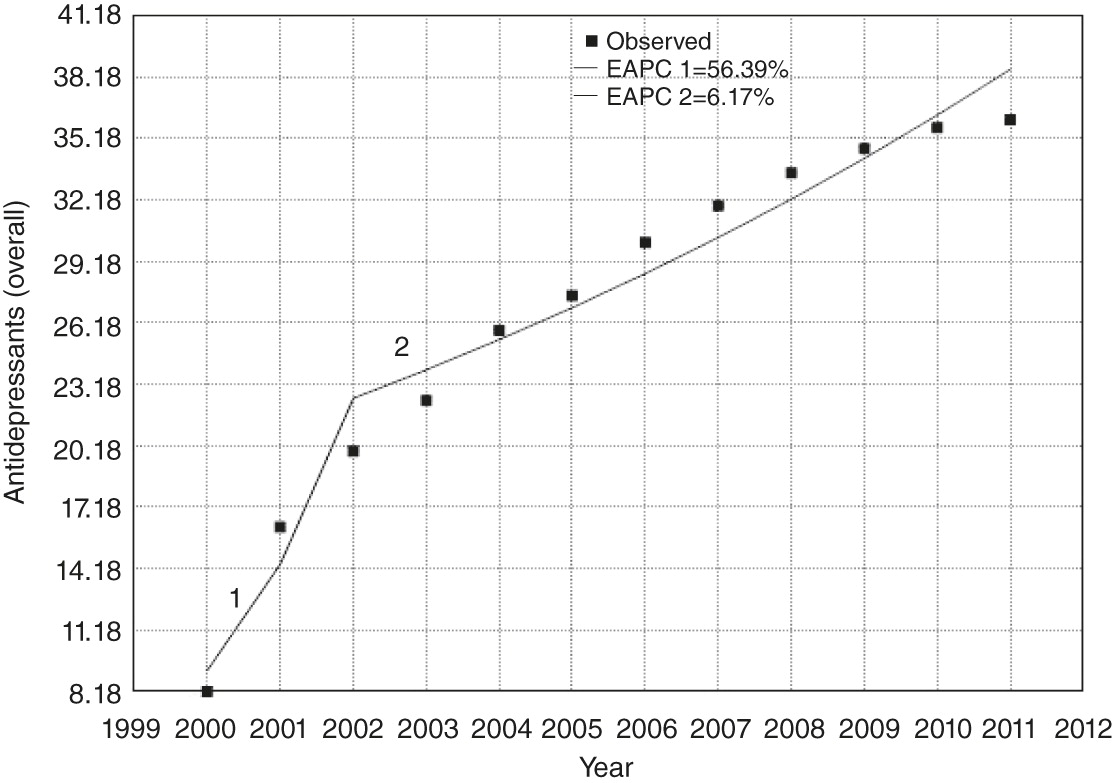

In the year 2000, the age-weighted consumption of antidepressant drugs was equal to 8.18 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day. Consumption doubled to 16.24 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day in the following year, which started a growing and continuous trend. In 2011, the last year of the study, antidepressant consumption accounted for 36.12 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day.

In the first nine months of 2011, expenditures for central nervous system (CNS) drugs accounted for €17.90 per person and were ranked third among expenditures by drug category. These drugs were ranked fourth in receipt of prescriptions (58.2 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day) (

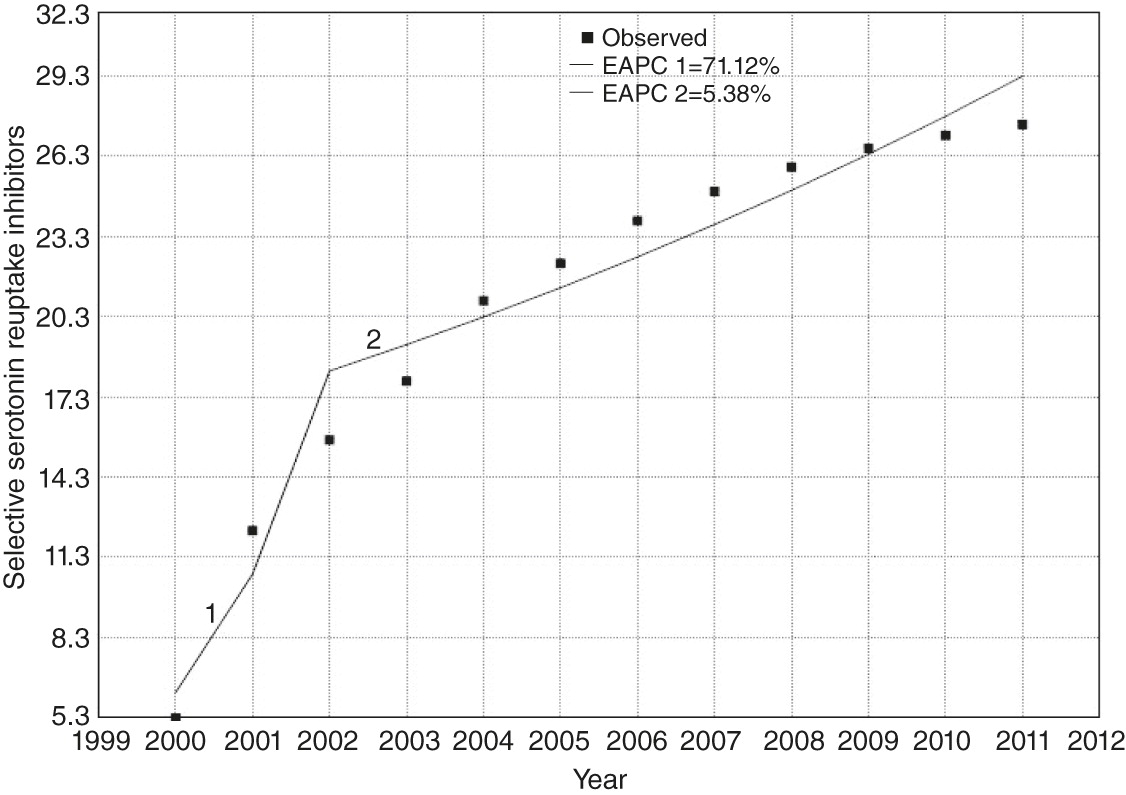

24). Among the CNS drugs, antidepressants were prescribed the most (36.1 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day) and of the antidepressants, SSRIs were prescribed the most (27.5 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day).

Trends analysis with the joinpoint regression software found a drastic increase in consumption of antidepressants in Italy between 2000 and 2011 (from 8.18 to 36.12 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day). A single joinpoint was found in 2002, with a reduction of EAPC from 56.39% between 2000 and 2002 to 6.17% from 2002 to 2011 but no real inversion (

Table 1). All the results were statistically significant (p≤.05). The 2000–2011 trend in consumption of antidepressant drugs is shown in

Figure 1.

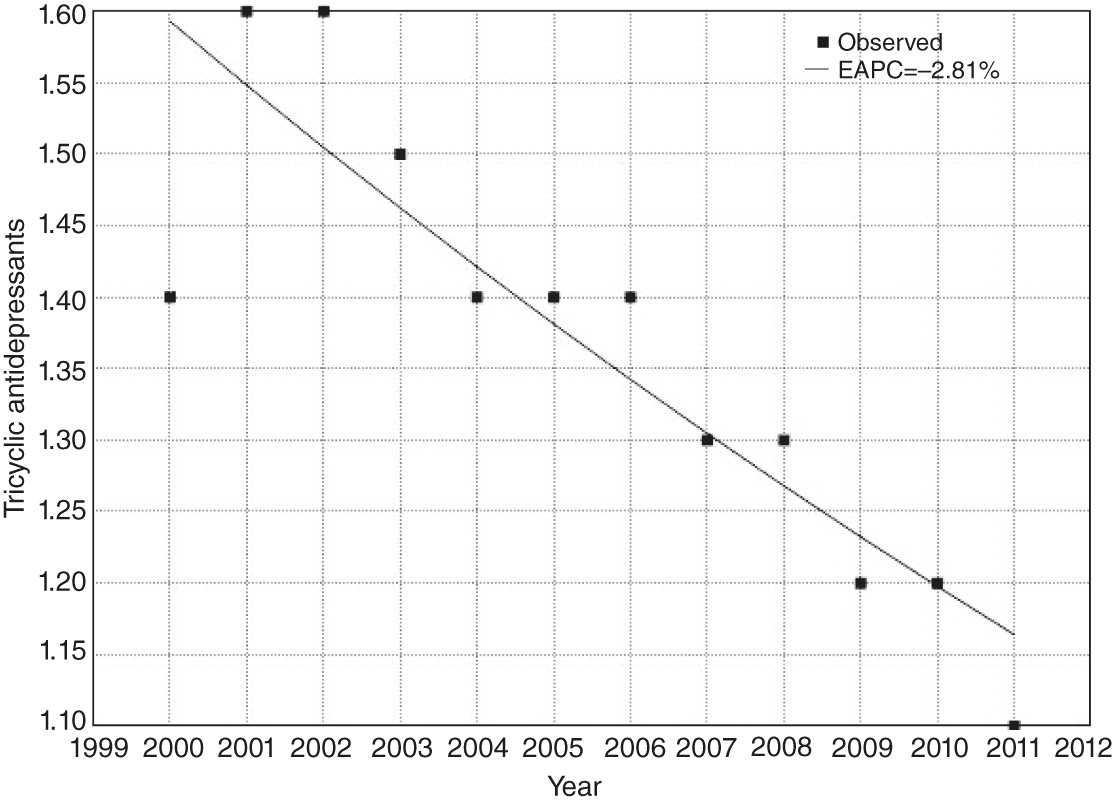

Additionally, we performed trend analyses by stratifying data by type of drug. Regarding TCAs, the data showed a reduction of consumption between 2000 and 2011, with no joinpoints (from 1.40 to 1.10 DDD per 1,000 inhabitants per day; EAPC=−2.81, p<.001) (

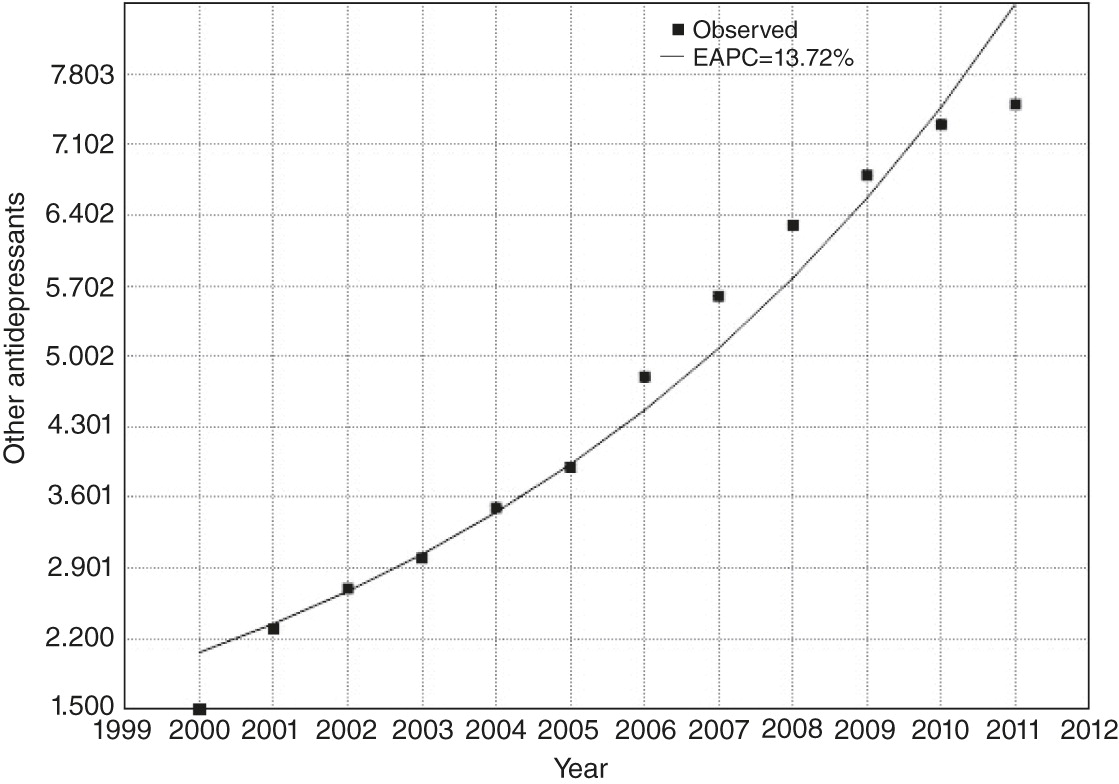

Figure 2). Conversely, SSRIs and the other products registered a great increase over time in consumption (

Figures 3 and

4). Interestingly, as was the case for the overall data, a joinpoint was shown for SSRIs in 2002 (EAPC=71.12, 2000–2002, and 5.38, 2002–2011). For the other products, the EAPC from 2000 to 2011 was 13.72, with no joinpoint. All these results were statistically significant.

Discussion

Our study assessed trends in the consumption of antidepressants in Italy from 2000 to 2011 by using the most recent data available. The results showed that consumption of antidepressants in Italy increased continuously since 2000, quadrupling by 2011. This rise in consumption affected SSRIs and the so-called other products, but not TCAs. A possible explanation for our findings is that SSRIs and the other antidepressants are largely preferred over TCAs for treatment of depression.

To date, studies of international trends indicate a huge increase in the use of antidepressants, especially after the introduction of SSRIs in the early 1990s, the publication of practice guidelines to diagnose and treat depression, and the development of efficient screening tools for depression in primary care (

7,

25–

30). The phenomenon of high rates of depression among primary care patients is well known in the developed countries, but up to 20% of those attending primary health care in developing countries also suffer from anxiety or depressive disorders, a fact that deserves to be highlighted (

31).

Notably, the increasing awareness of depression as an important health issue in the past decade has coincided with the arrival of several new classes of antidepressants that have increased the pharmacotherapy options for managing depression (

32,

33). These new, more expensive antidepressant drugs, which have been proven effective (

34), contribute to the rise in the total cost of antidepressants (

6).

However, according to a recent report by Connolly and Thase (

32), none of the newer drugs have strongly addressed the unmet needs in this area of therapeutics. Small studies of ketamine, which is among the newest treatment strategies, seemed to conclude that drugs modulating glutamatergic neurotransmission may be useful for exerting rapid and large antidepressant effects among patients who have not responded to an SSRI.

Another possible explanation of our findings may be related to the increase in the Italian population, from around 57 million people in 2000 to more than 60 million in 2011, but the increase is unlikely to explain the trends completely. Additionally, the growing use of antidepressants, as Ilyas and Moncrieff (

35) have suggested, may be attributed to an increase in long-term prescribing, to prescribing of antidepressants to people who are not diagnosed as having depression, and to the fact that many antidepressants have been marketed for anxiety disorders in recent years. In the United States, for example, data suggest that a majority of people with a prescription for antidepressants do not have a diagnosable mental disorder (

35). Furthermore, these drugs are often prescribed by general practitioners instead of psychiatrists, especially for episodes of mild depression or anxiety and for panic attacks (

14,

35).

Moreover, it is important to consider that from the beginning of 2001, SSRIs have been financed by the Italian National Health Service, a fact that contributed to a huge rise in consumption.

Furthermore, the growth of direct-to-consumer marketing increases the likelihood of beginning use of antidepressants, especially when out-of-pocket medication costs are low. Conversely, it does not necessarily increase utilization levels among those already taking antidepressants (

36).

Specific programs aimed at educating health professionals and patients about the correct use of these drugs can garner a huge change in future consumption, with the trend slope relatively little changed. This is a very important point for consideration by psychiatrists and public health professionals, given that implementing such programs may lead to consistent improvements in mental health and may have remarkable benefits related to expenditures by the National Health Service. Indeed, expenditures per capita for antidepressants showed a constant increase between 2010 and 2011 (.7%, SSRIs; 1.8%, other products (

24). Thus the role of prevention programs to contain and reduce these expenditures becomes even more important, especially in this time of national and global economic crises.

Although there are some positive aspects to the increased consumption of antidepressants, the fourfold increase in use of these drugs between 2000 and 2011 is alarming. Thus this study seems to suggest a need for the public health agenda to address the issue of antidepressant consumption, not only in Italy but also in Europe. Interventions designed to reduce the consumption of antidepressants could include, for instance, a new regulation about off-label prescribing of these drug categories, more rigid monitoring of use of these drugs, and a public health campaign to reduce risk factors for poor mental health—for example, by reducing stress. In this regard, a meta-analysis showed that depressive symptoms can be improved by as much as 11% through specific prevention programs designed to reduce depression, such as educational interventions, lifestyle interventions, anxiety management training, and cognitive therapy (

37). Consequently, providing these kinds of interventions is likely to contribute to a decrease in the consumption of drugs addressing depressive symptoms.

Surely, the limitations of this study should be considered. First, the measurement unit, DDD, is a proxy of consumption and does not necessarily reflect the real daily dose consumed. In this type of study, if the real prescribed daily dose is lower than the DDD, the use of DDD leads to an underestimation of the prevalence of use; in contrast, if the prescribed daily dose is higher than the DDD, the use of the DDD overestimates the number of patients who have a prescription for this medication. Another limitation of our study was that the AIFA database does not include drug consumption labeled as “out of pocket,” so our results refer exclusively to the consumption in the public and private settings that has an information flow monitored by the regions. In addition, reported data contained no information on compliance with therapy, and, therefore, the term “consumption” was used figuratively; at no time could we assume that the medication dispensed was actually consumed. Finally, the working group that prepared the OsservaSalute Report stratified the data by Italian region and type of drug but not by age and gender (data were not available).

Conclusions

Mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression, are less stigmatized by public opinion than they have been in the past. This change in perspective on neuropsychiatric illnesses affects compliance of drug treatment, perhaps more so because many of these drugs are often used also for the treatment of pathologies not strictly related to psychiatry, such as pain management. Thus, the implementation and monitoring of an effective flow of information are advisable, in order to easily identify the growing portion of patients who really need psychiatric treatment.

In addition, implementation of psychiatric support in the health care system, particularly in primary care, could be very useful (

38). Given the global increase in the consumption of psychiatric drugs, especially antidepressants, and because good mental health is the basis of economic growth and social development in Europe, the role of public health in mental health promotion has become more and more fundamental. Moreover, the relationship between mental health problems and socioeconomic and environmental factors add to the importance of monitoring trends in use of antidepressants, especially considering the possible effects of the current economic crisis on mental health.