One of the most pressing needs of individuals released from prison is employment (

1–

8). Analysis of employment rates have found that people with felony histories on average work 10%–23% less than those without felony histories (

2,

9–

11), resulting in an impact on national unemployment of .7%–1.7% (

12). Even when employed, those with prison histories frequently are in unskilled, low-paying jobs (

3,

13,

14). Employment difficulties are compounded by the high rates of substance use disorders and mental illness in this population, with 63% of state prisoners reporting drug use in the month before their offense and 56% reporting some symptoms of mental illness (

15).

The Bureau of Justice Statistics (

15) found that 10% of the prison population are veterans. With 1.5 million (

16) individuals incarcerated in U.S. prisons, as many as 150,000 are likely to be veterans. Overall, incarcerated veterans appear to have a more complicated legal involvement, having longer sentences than nonveterans and higher rates of some of the more serious crimes (including homicide and sex offenses) (

15).

Specific employment difficulties caused by or associated with incarceration have been identified. These include poor social connections, aging work skills, statutory restrictions, and stigma (

3,

13,

14); baseline criminogenic factors, such as antisocial cognition and antisocial associates (

17–

19); and prison-learned social behaviors, such as projecting violence to maintain safety, suppressing emotions, and distrusting others (

3,

20,

21). Previous research has demonstrated that structured programs targeting veterans with felony histories and mental illness, a substance use disorder, or both can assist veterans in overcoming these difficulties and in finding employment at a higher rate compared with basic vocational support (

22,

23). However, many veterans still do not benefit fully from these services (

23).

Supported employment, specifically evidence-based Individual Placement and Support (IPS), is an effective approach to improving employment rates for persons facing significant barriers (

24,

25). Discussed in detail elsewhere (

24,

26,

27), evidence-based IPS is founded on a set of core principles, including small caseloads, integrating treatment teams into vocational plans, no exclusion criteria, rapid job search, and services provided in the community. Beyond the core principles are the core components by which the principles are implemented, specifically, job exploration, individualized planning, job development and job carving, job coaching, and natural supports.

IPS has successfully assisted persons with spinal cord injuries (

28,

29), mental illness (

24,

30,

31), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD;

32), and cognitive impairment (

33–

35) to rapidly find employment; however, there has been limited focus on persons with felony convictions. A secondary evaluation of IPS for veterans with spinal cord injuries demonstrated that those who found employment had fewer average arrests and a lower rate of felony convictions (

36). In addition, recent work has shown IPS to be more beneficial than a job club in working with individuals with severe mental illness who have legal convictions, misdemeanors, or felonies (

37). Although studies often include persons with felony histories, it is unclear whether incorporating supported employment principles into existing programs can improve their results.

With the barriers facing these individuals, it is logical to predict that existing vocational rehabilitation programs could be improved by incorporating IPS principles. This study evaluated the combining of IPS principles into a standardized vocational program, About Face (AF), for veterans who have a mental illness, a substance use disorder, or both (

22,

23). This initial prospective study compared use of AF alone with use of AF that incorporated IPS principles to determine whether the additional services associated with IPS were beneficial in assisting ex-offenders to rapidly obtain employment.

Methods

Participants

A total of 130 veterans who had been incarcerated gave their informed consent for the study between September 2011 and November 2013. Inclusion criteria were a stated desire for competitive employment, a lifetime history of at least one felony conviction, and a formal diagnosis of a substance use disorder, mental illness, or both made by a U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) treatment team. Veterans unable to provide consent because of interfering psychosis or significant cognitive impairment, as determined by a doctoral-level clinical psychologist, were excluded from consideration. Those whose goals were to receive disability benefits because of unemployability or to immediately pursue the VA’s Compensated Work Therapy Program were not enrolled.

Of the 130 veterans who went through the consent process, seven (5%) were deemed ineligible for participation because of the lack of a documented mental illness or substance use disorder, 31 (24%) did not return to participate in any study activities, and four (3%) dropped out before completion of classes; these 42 were not randomly assigned to either study condition. The remaining 88 were randomly assigned through the use of a random number generator to one of two conditions: AF (N=39), a group-based vocational rehabilitation class, or AF plus IPS (AF+IPS; N=49). Two veterans, one from each condition, found employment prior to group completion and were excluded from the analyses. Two veterans from AF+IPS required long-term medical rehabilitation, were never medically cleared for employment due, and were excluded. The final analyses included 38 participants in the AF condition and 46 in the AF+IPS condition. Group assignment, although random, was not balanced at any time; as such, more veterans received AF+IPS, although the difference in condition sizes was nonsignificant.

Procedures

Veterans were recruited through flyers, word of mouth, and presentations by study staff. Enrollment and consenting followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the VA North Texas Health Care System’s Institutional Review Board.

All veterans participated in the AF program, a one-week standardized vocational rehabilitation group–based program that has been successful in assisting this population with finding employment. The group, described in detail elsewhere (

22,

23), typically includes three to seven participants. Within the group, veterans begin by developing a list of employment experiences, aspirations, and skills. Veterans develop a basic but professional resume simple enough to prepare with word processing software. A large section of the group focuses on the specific problems often encountered by veterans with felony histories, with examples and rationales to help develop personalized responses.

Veterans receiving AF received only the group-based program. Veterans assigned to AF+IPS received the standardized group and additional services based on the IPS model of supported employment. IPS was provided by one of two supported employment specialists (SESs). Both SESs were rehabilitation counselors trained either through formal coursework and practicum experience or through attending specialized training. Both were supervised by a clinical psychologist with experience overseeing IPS programs.

Although the IPS model served as the basis for the intervention in the AF+IPS condition, several deviations were incorporated, and as such, the program used was not viewed as meeting the standards of evidence-based supported employment (

38,

39). In full-fidelity, standard IPS, there are no prerequisites to beginning IPS, the SES is integrated into only one or two treatment teams, and caseloads are relatively small (20–25, for example). These features are in contrast to the IPS used in this study, in which all veterans were required to participate in the vocational classes immediately after enrollment. Although classes were required, all veterans in AF+IPS began the job search process within two weeks and the SES contacted employers face to face within one month of enrollment of 42 of 46 (91%) veterans. This pace was consistent with the expectation in standard IPS that first contact with an employer will occur within one month of enrollment. In contrast to standard IPS, in AF+IPS, higher caseloads of up to 35 per SES were allowed due to the lower incidence of serious mental illness compared with typical populations for IPS. Finally, the difference in the level of treatment team involvement—that is, less frequent contact due to more unique teams—was predictable because veterans were drawn from the entire health care system. In fact, veterans enrolled were covered by four different mental health teams, two primary care clinics for veterans without an identified mental health team, and five homelessness programs. Using fidelity rating anchors based on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration fidelity rating form (

40), we analyzed differences between fully implemented evidence-based supported employment and the implementation targets of the study (

Table 1).

Data Collection

Baseline demographic, legal, and psychosocial information, including recent housing and employment history, was collected during face-to-face interviews; study staff used standardized questions. Diagnostic data were collected from the medical record.

Veterans were required to have a minimum of one face-to-face contact and at least one phone contact each month to complete surveys and update results. Employment data were obtained initially through self-report and then confirmed by either an SES’s or study coordinator’s review of paystubs, community visits, contacts with employers, or other means.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous dependent variables were tested for normality with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous parameters, reported as means±SD, were compared with one-way analysis of variance, and discrete parameters, reported as N and percentages, were compared with the Pearson chi square test or Fisher’s exact test for small sample sizes. When any dependent variables were not normally distributed, Mann-Whitney U values were computed. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were performed to compare the groups on time until employment. Analyses were performed with SPSS 22.0 for Windows.

Results

Sample Description

A majority of the study sample (N=81 of 84, 96%) was male, and the mean age was 52.3±5.9. Only six (7%) veterans were married. Most participants were African American (N=57, 68%), followed by white non-Hispanic (N=23, 27%), and white Hispanic (N=3, 4%); one (1%) veteran was of mixed race-ethnicity. Two-thirds of the sample (N=56, 67%), had been homeless in the past year. The sample had 12.5±.9 years of education. The most common psychiatric diagnosis was a substance use disorder (N=74, 88%), followed by depression (N=38, 45%), PTSD (N=8, 10%), and cyclical mood disorder or psychosis (N=5, 6%). Comorbid substance use disorder and a non–substance-related psychiatric diagnosis was common (N=48, 57%), as was having at least one psychiatric hospitalization (N=23, 27%) and at least one past suicide attempt (N=13, 16%). No differences in demographic variables between groups were identified.

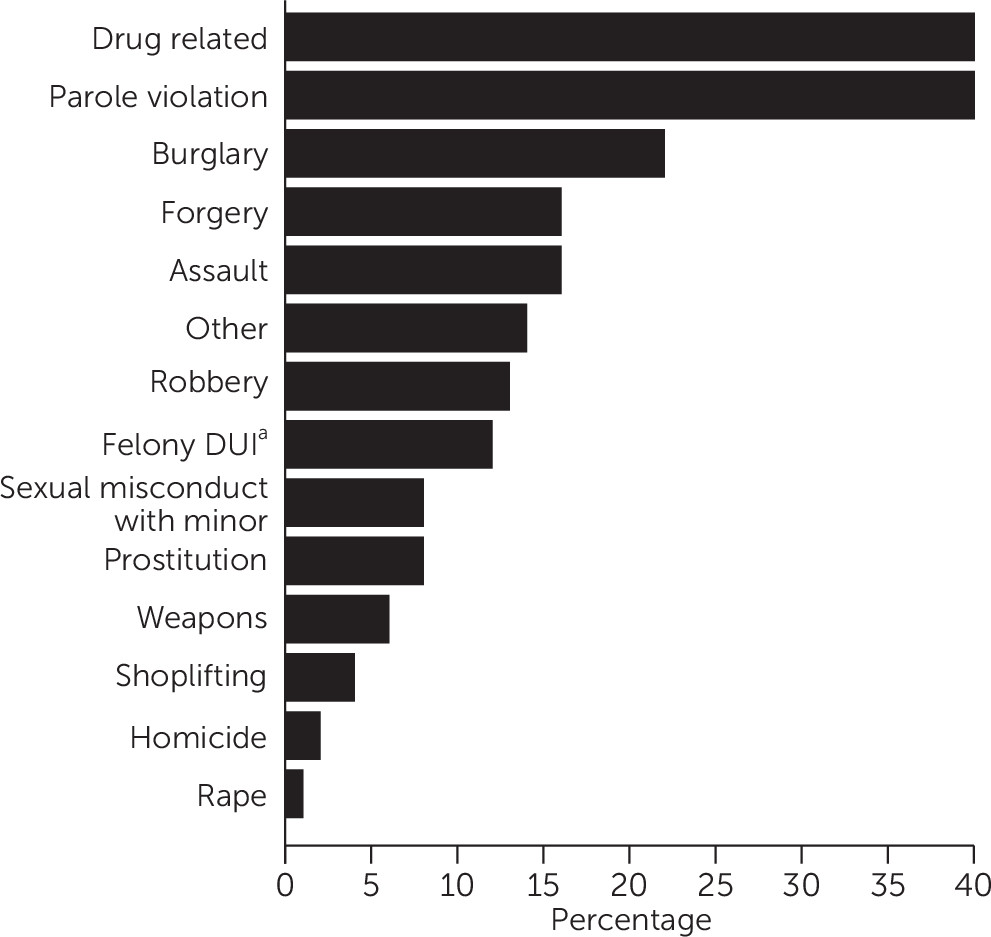

Overall, the sample demonstrated a high level of historical legal involvement. As shown in

Figure 1, the most common causes of lifetime incarceration were drug charges (N=34, 41%) and parole violation (N=34, 41%), burglary (N=18, 21%), and forgery (N=14, 17%). The mean number of incarcerations was 1.6±1.6. The sample averaged 83±96 months of lifetime incarceration and 30±36 months of incarceration within the past ten years. There were no significant differences between conditions. The range of lifetime incarceration was from one month to 396 months. Lifetime months of incarceration, months of incarceration in the past ten years, and time since last incarceration were not significant predictors of employment at the 180-day follow-up.

Employment history, specifically months since last full-time employment, was found to be a significant predictor of employment at 180 days (χ2=4.5, df=1, p<.03). Mann-Whitney U tests revealed no significant difference between AF and AF+IPS in the time since last full-time employment.

The Between-Groups Employment Difference

The Pearson chi square test was used to evaluate rates of finding employment within 90 and 180 days. Rates of employment were statistically similar at 90 days; 15 (33%) who received AF+IPS found employment compared with six (16%) who received AF. At 180 days, 21 (46%) receiving AF+IPS found employment compared with eight (21%) who received AF (χ2=5.9, df=1, p<.05; odds ratio=3.5). The AF+IPS condition continued to show significant differences after analyses controlled for the time since last full-time employment (χ2=4.1, p<.05; odds ratio=2.9).

During the follow-up period, six veterans, four receiving AF and two receiving AF+IPS, opted to participate in the VA’s Veterans Retraining Assistance Program, a program focused on retraining rather than on direct employment. Employment rates with AF+IPS remained superior (χ2=4.0, df=1, p<.05) after removing these veterans’ data from the analyses.

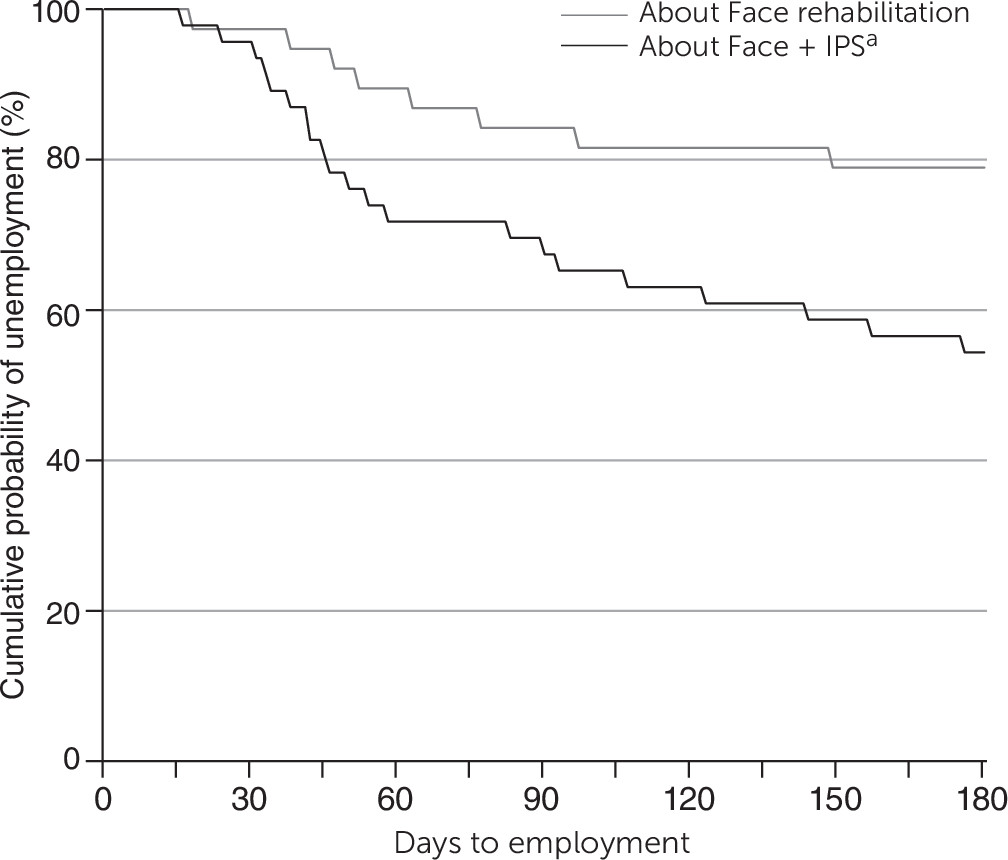

To address differences between the two conditions on time until employment, we ran Kaplan-Meier survival analyses for employment at 90 days and employment at 180 days. The groups were similar in rate of employment at 90 days. Analysis of time until employment at 180 days revealed that the veterans receiving AF+IPS were significantly more likely to obtain employment and obtain it sooner than those receiving AF alone (log rank χ

2=5.47, df=1, p=.02;

Figure 2).

Shapiro-Wilk tests of normality revealed all of the continuous employment outcomes (number of days employed, average hours worked, total hours worked, and total wages) to be nonnormally distributed. In the full sample, Mann-Whitney U tests revealed that AF+IPS resulted in significantly more days employed, hours worked, total hours worked, and total wages compared with AF (

Table 2).

Evaluating the data in both conditions for only those employed, we found that most outcomes were similar between conditions. Although the groups were not significantly different, the employed veterans receiving AF earned slightly more in total and per hour than those who obtained employment via the AF+IPS condition. Those receiving AF alone who found employment had fewer months of lifetime incarceration than those in AF+IPS (50±66 versus 62±81). Also, those not finding employment in AF had fewer months of lifetime incarceration than those in AF+IPS (88±89 versus 112±124).

The level of engagement in IPS was assessed by evaluating the number of IPS-related contacts the participant had with the SES. Those who found employment had significantly more contacts with the SES prior to employment, 7.1±4.0, than those who did not find employment, 4.6±3.0 (p=.04). Over 80% of all contacts involved going into the community with the veteran to look for employment or going to interviews with the veteran.

We reviewed the types of employment obtained by comparing the number who found jobs considered typical for those with felonies (including jobs in warehousing, construction, and housekeeping). Overall, 15 of 21 (71%) receiving AF+IPS found employment outside the traditional employment areas compared with three of eight (38%) receiving AF. Initial employment goals and expected salaries were compared with jobs ultimately taken. Although the numbers were too small to make definitive statements, of those who found employment, one (13%) veteran receiving AF was hired into a job above his or her initial expectations compared with veterans receiving AF+IPS, in which five (24%) veterans were hired above their initial expectations and two (10%) found initial employment below their expectations.

Discussion

This study was the first to incorporate principles of IPS into an existing successful vocational program with veterans who were formerly incarcerated, and it continues to build on validated vocational programs demonstrated in previous research. Although based on the principles of IPS, the variation used did not meet the standards of evidence-based IPS; however, the study demonstrates the superiority of the inclusion of IPS principles into a standardized vocational program compared with the employment program alone. As predicted, the inclusion of services based on IPS principles was superior to a group-only condition in almost all areas of importance, including time to employment, rate of employment, total days worked, and total income.

Evidence suggests that incarceration history may be less of a barrier for those receiving AF+IPS. Those who found employment through AF+IPS had been incarcerated a year longer than those finding employment with AF alone, whereas those not finding employment in AF+IPS had two years more lifetime incarceration than those in AF.

The differences between the conditions in legal histories of those finding employment suggest that the inclusion of IPS principles creates more employment opportunities for those with more complex legal histories. A number of factors are hypothesized to contribute to the higher level of success of veterans with more complex legal situations. The first is by confronting the stigma associated with incarceration. Although stigma exists across all levels of incarceration, those with more complex histories—for example, more time incarcerated, more incarcerations, and more severe types of crimes committed—may experience a higher level of stigma. The SES acts as an advocate and can focus an employer on the applicant, rather than on the applicant’s legal history. Second, the SES’s work with employers to create positions may lead the employer to emotionally invest more in the success of the veteran and to willingly adjust the requirements of the job to improve the applicant’s chance of success. A third factor is the encouragement given by the SES treatment teams. Veterans with more complex histories may be more easily discouraged or give up on searching for employment earlier than others due to the realities of their chances of finding a permanent position. The SES is able to address these concerns with the veteran directly and work with the treatment team to keep the veteran engaged in the employment search.

Overall, the most significant factor contributing to employment success appeared to be the rapid engagement with employers. The SES creating novel employment opportunities was also viewed as very successful; an example of this was an employer who was willing to create an hourly mechanic apprentice position for a veteran with skills as a mechanic but no certifications. In addition, across conditions, working on interviewing skills during the class period was identified as important, especially in developing individualized ways of discussing past felony convictions.

Throughout the study, lack of engagement in the job-search process by participants was reported by the SESs as the most significant barrier. Although not tracked for this study, factors such as self-efficacy (

41,

42), competing priorities (

41), and overwhelming existing financial obligations (

43) (such as child support) are areas previous studies identified as affecting employment and could be a focus in future work to improve outcomes.

It is important to note that the number of days worked and total pay were relatively low in both conditions. This was primarily a function of the time until employment, which, although superior in the supported employment condition, was still, on average, over four months. This factor highlights the significant difficulty this population has in obtaining employment, even with one of the most supportive modalities. Once veterans were employed, they tended to work, on average, close to full-time hours.

Several limitations to the study affect the overall generalizability. First, the population served comprised veterans exclusively. Veterans frequently have access to a higher number of general services, including housing, which may allow them to be able to focus more than nonveterans on employment. However, these services may decrease the priority of employment because there may be less pressure to establish steady income, so the impact of this limitation is unclear.

The veterans who received services did not demonstrate high rates of the most severe mental illness and primarily had substance use disorders, a finding consistent with expectations based on the population evaluated. Also, given that this was the initial study evaluating the addition of a modified IPS intervention, replication is required to ensure the stability of the findings.

Again, several planned deviations from evidence-based IPS were incorporated into the program. All veterans were required to participate in the AF groups. Overall, the involvement of the SES with the veterans’ treatment teams was, as expected, low based on several factors, including the preference of the veteran that the SES not give updates to or engage the mental health teams; the relatively infrequent treatment team contact, with several veterans not having a consistent provider; and the wide diversity of treatment teams used by veterans. A related but unplanned deviation was that follow-along supports to assist the veteran and the employer to coordinate vocational and support needs were used with only half the employed veterans, again based on the preferences of the veteran. Anecdotally, several veterans indicated that they felt uncomfortable with the SES’ communicating with the treatment teams and employers after employment, expressing feelings of being treated “like a child.” It was unclear whether these perceptions indicated a lack of trust consistent with incarceration behaviors, evaluation anxiety over being evaluated by employers and treatment team members, or the difficulty of the SES in explaining the benefit of the higher level of involvement. These domains should receive an increased level of focus in future studies.

One additional modification from traditional implementation was that SESs were allowed to carry caseloads of up to 35, because of the perception that the lower level of severe mental illness would allow for less intensive engagement. However, this may have been an inaccurate assumption. Although the veterans had a lower preference for staff engagement, the results demonstrate that this population is vulnerable to continued unemployment. As such, maintaining a lower staff-to-patient ratio is recommended until optimal levels can be determined.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the benefit of incorporating IPS principles into a structured vocational program across important employment domains, including time to employment, total hours worked, and improved income. Continued evaluation of the benefits, including impact on incarceration, hospitalization, and substance use, across an extended follow-up period is being conducted.