Nonadherence to prescribed medication is a major cause of relapse, rehospitalization, and increased health care costs in the treatment of schizophrenia (

1). Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic medications, which can be administered every two to four weeks, are used to reduce nonadherence and relapse. The use of LAI versions of first-generation antipsychotics has been limited, in part because of concerns about the risk of extrapyramidal side effects. Risperidone microspheres, an LAI version of the second-generation antipsychotic risperidone, was introduced in 2003, but it must be refrigerated before use, reconstituted with a diluent, and administered every two weeks. In 2009, paliperidone palmitate (PP), an LAI version of risperidone’s active metabolite, became available. It can be administered monthly and does not require refrigeration or reconstitution. Because of these logistical advantages, PP was considered to be an important advance in LAI antipsychotics (

2), although its high cost has raised uncertainty about whether its costs are justified by greater benefits.

Recent trials have raised some doubts about the clinical advantages of oral second-generation antipsychotics compared with first-generation oral antipsychotics (

3–

6). Some newer antipsychotics appear to cause significant metabolic problems (

7), and randomized trials have failed to find advantages of LAI versions of second-generation antipsychotics compared with oral formulations of the same drugs (

8,

9). However, one recent study found robust benefits for LAI versus oral risperidone in first-episode psychosis (

10).

In view of these uncertainties, a randomized controlled trial was designed to compare PP and the first-generation LAI antipsychotic haloperidol decanoate (HD). The study found that PP provided no advantage in preventing relapse but was associated with greater weight gain and reduced risk of akathisia (

11). This study evaluated the cost-effectiveness of PP and HD by measuring the relative effectiveness of PP and HD with respect to health status, including both symptoms and side effects, of people with schizophrenia and analyzing whether any health advantage provided by PP merits its greater cost.

Results

Of the 311 patients who were screened and randomly assigned to each group, 290 patients (PP, N=145; HD, N=145) received at least one injection and at least one postbaseline assessment and were included in the primary analysis of the original study (

11). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the 290 patients in the primary analysis are presented in the earlier article (

11).

Dose

In the initial month of LAI treatment, which included doses on day 1 and day 8, the mean dose was 325 mg for PP and 94 mg for HD. Subsequently, the mean monthly dose of PP ranged from 129 to 169 mg and the mean monthly dose of HD ranged from 67 to 83 mg.

Summary of Previously Published Results

In the primary analysis of the original study, there was no statistically significant difference in the time to efficacy failure for patients taking PP (49 days) or HD (47 days) (site-stratified log rank p=.90; adjusted hazard ratio=.98, 95% confidence interval [CI]=.65–1.47, adjusted for site and baseline PANSS score). On average, patients taking PP gained weight progressively over time and those on HD lost weight (p<.001).

Patients taking HD experienced more akathisia compared with patients taking PP, as indicated by greater increases in average (SD) global scores on the Barnes Akathisia Scale (.73 [.59–.87] and .45 [.31–.59], respectively, p=.006). There were no statistically significant differences between groups at each time point in changes in ratings of parkinsonism (measured by the Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Scale) and in decreases in PANSS total scores compared with baseline.

QALYs

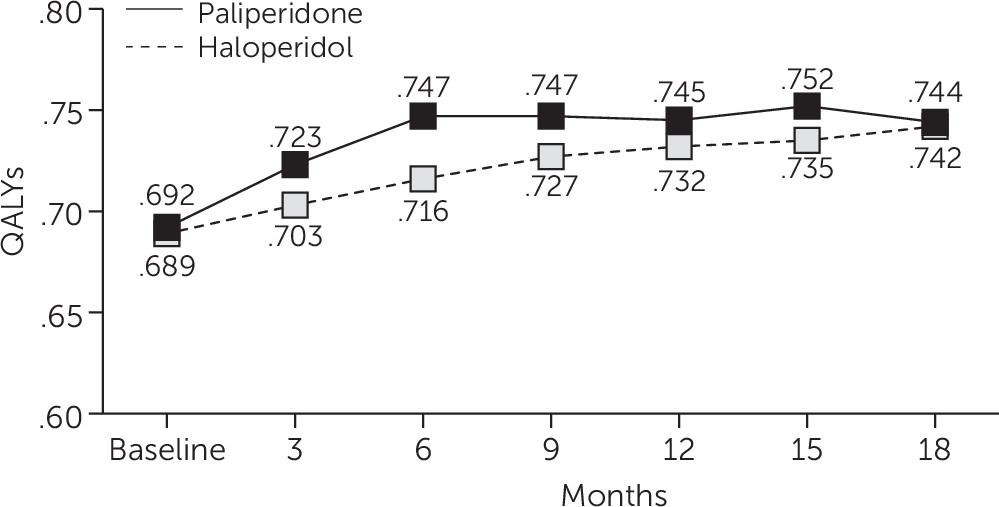

Mixed-model analysis of QALYs as measured by the algorithm described above showed that scores for PP were slightly higher compared with scores for HD, with an average difference of .0297 QALYs over 18 months (p<.03) (

Figure 1).

Costs

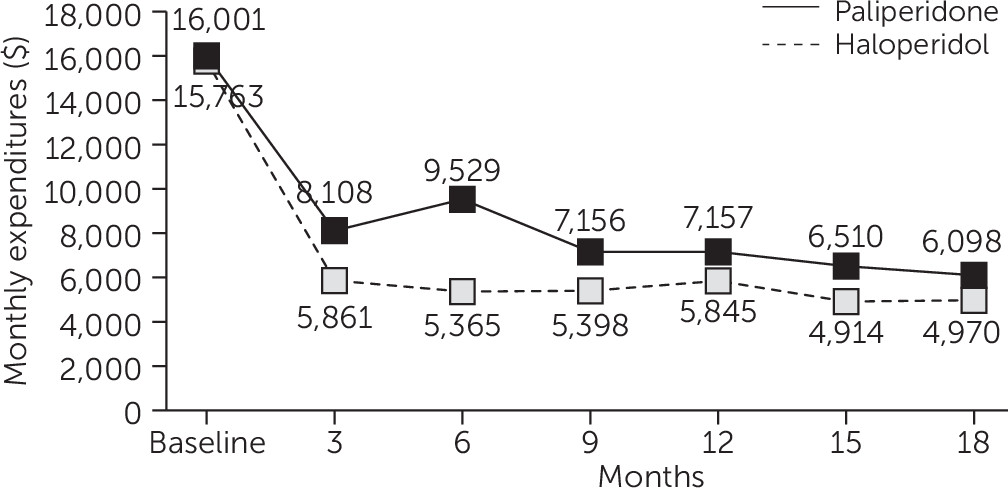

Antipsychotic drug costs were $2,213 greater per quarter for the PP group compared with the HD group (p<.001) (

Table 1). There were no significant differences between the two groups in other medication costs. Nor were there any significant differences between the treatment groups in total inpatient and outpatient mental health and medical-surgical services use or related service costs (excluding medications) (

Table 1). The average total costs per quarter for services and medications during the 18-month follow-up period were $2,100 greater for the PP group compared with the HD group (p=.003) (

Table 1).

Figure 2 depicts total costs per quarter for both groups.

Cost-Effectiveness and Net Health Benefits

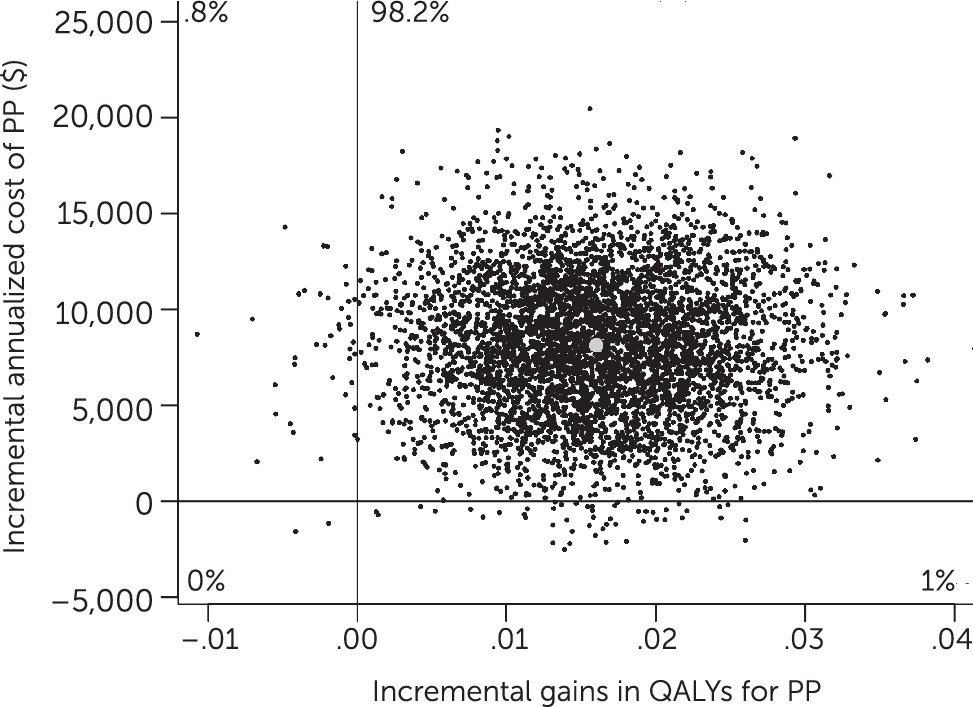

Dividing incremental costs by incremental benefits in the bootstrap analysis generated an ICER of $508,241 per QALY for PP compared with HD (

Figure 3), with 98% of observations falling in the upper-right quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane, indicating greater benefits for PP as well as greater costs.

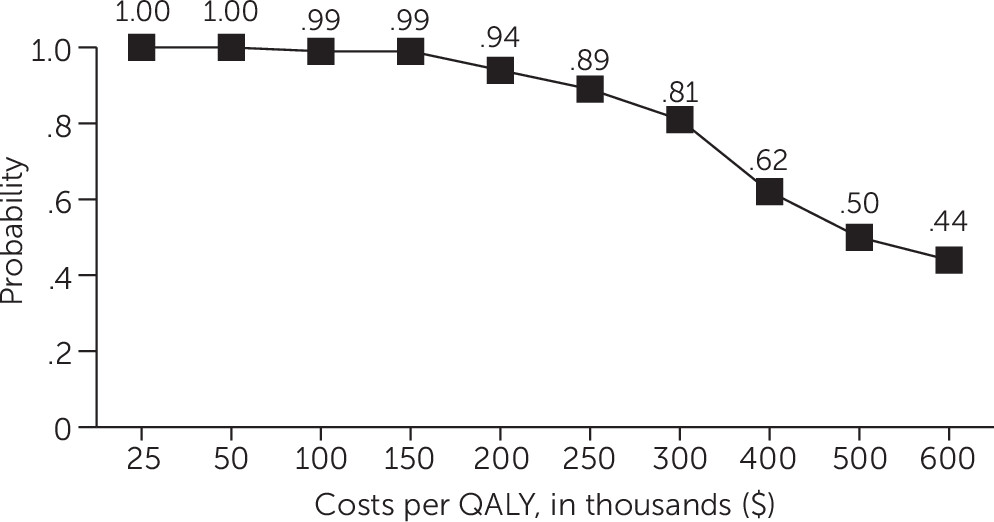

Analysis of net health benefits expressed in dollars at each estimated value of a QALY showed that HD had a .95 probability of being more cost-effective compared with PP at QALY values less than $150,000 and a .81 probability of being more cost-effective compared with PP at a QALY value of $300,000 (

Figure 4). The probability that HD was more cost-effective than PP declined steadily at QALY values greater than $300,000 (

Figure 4), falling to .50 at a QALY value of $500,000 and to .44 at a QALY value of $600,000.

Discussion

This study used a disease-specific method to calculate QALYs associated with various health states among people diagnosed as having schizophrenia. It found that treatment with PP resulted in a statistically significant but small advantage in health status. However, because PP remains on patent and has relatively high acquisition costs, it is not a cost-effective treatment choice under a wide range of estimates of the monetary value of a QALY. That was true even though we used the lowest available estimate for the cost of the drug. For example, on the basis of the Federal Supply Schedule, 117 mg of PP was priced at $758 compared with a published average wholesale price of $889 and online retail prices ranging from $1,023 to $1,106 (

http://www.goodrx.com/paliperidone-palmitate#/?filter location=&coords=&label=Invega+Sustenna&form=syringe&strength=0.75ml+of+117mg&quantity=1.0&qty-custom) as of July 16, 2015. Thus our findings would be sustained under a wide range of 2015 prices for PP, although prices are likely to drop when generic versions of the drug appear after patent protection runs out in 2017.

Many studies of newer second-generation antipsychotics end up with ambiguous findings showing that some side effects are less severe with new treatments, but others are more severe. The QALY measure used in this study (

13) provides a rational approach to combining data on symptoms and major side effects in a single measure. In addition, selective inclusion of only individuals judged by their clinicians to be likely to benefit from LAI treatment, who most closely resemble patients prescribed LAI treatments in real-world practice, enhanced the study’s external validity.

There has been controversy about the monetary value that should be assigned to a QALY in cost-benefit analysis. On the one hand, some governments have long used $50,000 as the appropriate value of a QALY for policy making (

25). However, this estimate was first established in 1982 (

26), and by 2011, when this study was initiated, it would have reached $117,000 just by adjusting for inflation alone. A more recent valuation of a QALY suggested a range from $183,000 to $264,000. This valuation was based on an empirical estimate of the cost-effectiveness of treatments available in 2003 compared with care available in 1950 and of the implicit cost-effectiveness of unsubsidized insurance compared with self-pay care.

Although HD was clearly more likely to be cost-effective compared with PP at a QALY valuation of $50,000 (.998 probability) and at an inflation-adjusted valuation of $117,000 (.985 probability), it also had a .94 probability of being more cost-effective at a QALY value of $200,000 (the lower bound of the estimate by Braithwaite and others [

26]) and a .81 probability of being more cost-effective at a QALY value of $300,000 (the upper-bound estimate by Braithwaite and others [

26]). The probability that HD was more cost-effective than PP declined only at values of $500,000 and $600,000 per QALY, far higher than the values that are currently accepted. Thus HD was substantially more likely than PP to be cost-effective at a broad range of estimates of the value of a QALY as well as of the cost of PP.

The results of this study are consistent with the only other RCT-based cost-effectiveness study of an LAI second-generation antipsychotic. That study found that LAI risperidone (

8) was not associated with significantly greater benefits on multiple measures compared with a doctor’s choice of oral medication. However, the LAI treatment was associated with more neurological side effects and significantly increased drug costs. Total health care costs were 7% greater among the users of LAIs compared with users of oral medication, but the difference was not statistically significant (

28).

Several RCTs have found no benefit of LAI second-generation antipsychotics compared with oral antipsychotics (

29–

32). Two studies found positive benefits for LAI risperidone (

9,

33), and a recent publication found robust benefits for LAI risperidone compared with oral risperidone for patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis (

10). Although there is mixed evidence of the superiority of second-generation antipsychotic LAIs compared with oral medications, the use of LAIs is supported by systematic reviews (

34,

35) and expert panels (

36). This study is the only RCT to compare the cost-effectiveness of first- and second-generation LAIs.

Given that several newer LAI antipsychotics are now on the market in the United States with high acquisition costs associated with being on patent, total national expenditures on these drugs may rise rapidly. The results of this study should encourage consideration of older, less expensive drugs, such as HD. Used at moderate dosages in this study, HD’s overall effectiveness and tolerability were only slightly worse, as reported here, than those of PP, and it had clear advantages in cost-effectiveness. When generic versions of the newer LAIs become available, the cost-effectiveness calculations will undoubtedly change. In the meantime, trial evidence appears to indicate that HD is a cost-effective choice. A rational policy for treatment of chronic schizophrenia might limit use of the more expensive LAIs to patients who do not benefit from or cannot tolerate HD.

Several methodological limitations require comment. The QALY algorithm used in this study has not been further validated since its initial validation. It must be acknowledged that people with serious mental illness may have difficulty responding to standard gamble choices, even when they are presented with simplified graphic displays. In addition, although the QALY responses were weighted by using sociodemographic characteristics of the U.S. population, QALY values may vary by unmeasured respondent characteristics. Imperfect as this measure may be, the results were consistent with those observed on individual measures in the original article from this study (

11) and provide a rational empirical basis for assigning monetary values to health states.

Second, utilization data were based on self-report estimations by patients of service use and published estimations of unit costs rather than on verified service use or actual unit costs, and there were substantial amounts of missing data from the study. If respondents underestimated their service use, which might be expected as a result of memory lapses, actual group differences could have been underestimated as well. Missing data were addressed in the mixed models by using all available data, and study dropout rates were similar to those in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study by the National Institute of Mental Health (

5,

37) and others (

37), but recall biases cannot be ruled out. In spite of these limitations, the findings of this study appear to be robust in a number of sensitivity analyses representing alternative assumptions and methods of analysis.

Acknowledgments

The following investigators conducted the study: Lawrence Adler, M.D., Glen Burnie, Maryland; Peter Buckley, M.D., Augusta, Georgia; Matthew Byerly, M.D., Dallas; Stanley Caroff, M.D., Philadelphia; Cherilyn DeSouza, M.D., Kansas City, Missouri; Dale D’Mello, M.D., Lansing, Michigan; Deepak D’Souza, M.D., New Haven, Connecticut; Fred Jarskog, M.D., Chapel Hill, North Carolina; Venkata Jasty, M.D., Detroit; Eric Konicki, M.D., Cleveland; Matthew Macaluso, M.D., Wichita, Kansas; J. Steven Lamberti, M.D., Rochester, New York; Joshua Kantrowitz, M.D., New York; Joseph McEvoy, M.D., Butner, North Carolina; Del Miller, M.D., Iowa City, Iowa; Robert Millet, M.D., Durham, North Carolina; Max Schubert, M.D., Waco, Texas; Martin Strassnig, M.D., Miami; Sriram Ramaswamy, M.D., Omaha; Andre Tapp, M.D., Tacoma, Washington; and Sarah Yasmin, M.D., Palo Alto, California.