Individuals with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, have higher morbidity and earlier mortality than individuals without serious mental illness (

1–

6). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration defines serious mental illness as the presence of a

DSM-IV diagnosis of mental illness (excluding substance use and developmental disorders) that results in serious functional impairment (

7). Persons with serious mental illness have high rates of other chronic diseases and die 13 to 30 years earlier than persons in the general population, primarily from cardiovascular disease and other treatable general medical conditions with modifiable risk factors (

1,

6,

8–

11). Individuals with serious mental illness have high rates of smoking and alcohol consumption, poor nutrition and obesity, physical inactivity, unsafe sexual behavior, and intravenous drug use (

6,

10–

15).

Despite high rates of general medical comorbidities, people with serious mental illness face barriers related to accessing primary care (

8,

16). In addition to the burden of the disorganizing symptoms of their mental illness, comorbid substance use disorders, social isolation, poverty, and homelessness often make it difficult to connect or engage individuals with serious mental illness with primary care (

9). For example, in one study of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) patients, those with serious mental illness, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and substance use disorders, had lower use of primary care services than those without these disorders, even after the analysis controlled for general medical comorbidity (

16). Difficulty accessing primary care is likely one reason that receipt of guideline-recommended metabolic screening and other preventive services (including immunizations, cancer screenings, and tobacco cessation and nutrition counseling) is lower among individuals with serious mental illness (

8,

9,

17,

18).

Although policy makers, researchers, and providers are increasingly focused on determining characteristics of “high utilizers” of health care—particularly users of acute and emergency services (

19,

20)—little research has explored the characteristics of low or nonusers in this vulnerable population, especially those who are low users of primary care. What is known about utilization among individuals with serious mental illness is based almost entirely on care delivered in the VA health care system, the largest integrated public-sector health care system in the United States, but one that differs greatly from other public or private health care systems (

21). The purpose of this study was to characterize the use of outpatient general medical services among a large cohort of individuals with serious mental illness who were being served in California’s public mental health care system. We examined predictors of nonpsychiatric outpatient visits to identify subpopulations that will require targeted outreach.

Results

Characteristics of the 56,895 individuals in the sample are summarized in

Table 1. Just over half of the sample (55%) was female. Almost all participants (N=55,188, 97%) were taking second-generation antipsychotics, and some were taking first-generation antipsychotics (N=1,707, 3%). The largest proportion of participants was white (38%), followed by Hispanic (20%) and non-Hispanic black (19%). Half of the individuals had schizophrenia spectrum disorders (52%).

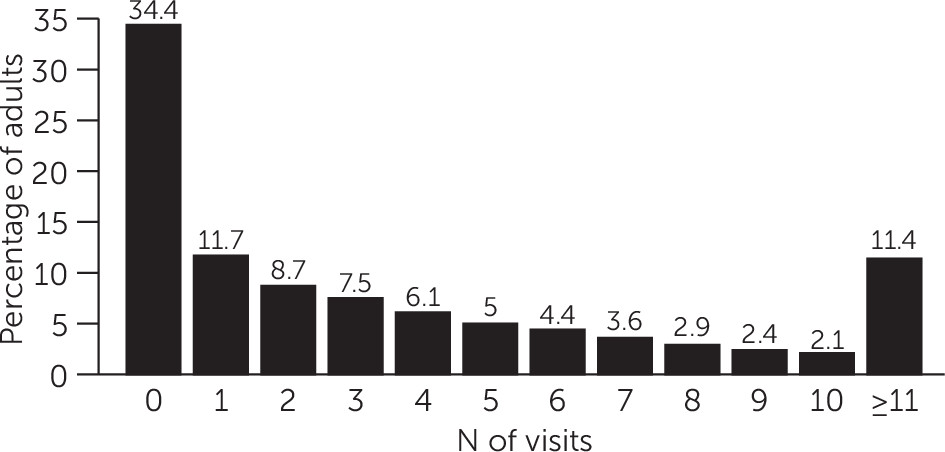

Overall, one-third (34%) of individuals had no outpatient general medical visits during the one-year study period (mean±SD=4±6 visits, median=2, range 0–152) (

Figure 1). Of those with any outpatient medical visits, 89% of the visits were categorized as returning patient and 8% were categorized as new patient; less than 3% were categorized as consult visits (patients could have multiple types of visit). Less than 3% of individuals (N=1,706) had 20 or more visits. Individuals with managed Medicaid were more likely to have outpatient general medical visits than those with fee-for-service Medicaid (77% versus 60%, p<.001).

In bivariate analyses, individuals with schizophrenia were less likely than those with other psychiatric conditions to have an outpatient general medical visit (

Table 2). Similarly, men, young adults, and people with comorbid drug or alcohol use disorders were less likely to have an outpatient general medical visit.

In multivariate analyses, individuals with schizophrenia were less likely than those with other psychiatric conditions to have an outpatient general medical visit. In this adjusted analysis, older individuals were more likely than young adults (ages 18–27) to have at least one outpatient general medical visit (ages 28–47, adjusted relative risk [ARR]=1.07; and ages 48–67, ARR=1.19). Women were more likely than men to have at least one outpatient general medical visit (ARR=1.29). Compared with whites, blacks were less likely to have an outpatient general medical visit (ARR=.93). Hispanic ethnicity was not significantly associated with having an outpatient general medical visit. Asians and Pacific Islanders were more likely than whites to have at least one outpatient general medical visit (ARR=1.09). Rural dwellers were 36% less likely than urban dwellers to have such a visit (ARR=.64), although the number of rural dwellers in the cohort was low. Individuals given a diagnosis of a drug or alcohol use disorder by a psychiatrist were less likely than those without these diagnoses to have an outpatient general medical visit (ARR=.95). Sensitivity analysis confirmed that findings did not differ by enrollment in fee-for-service or managed Medicaid [see online supplement].

Discussion

In a large cohort of Medicaid recipients with serious mental illness in California’s public mental health care system, one-third of patients (34%) did not utilize outpatient general medical services in a one-year period. These utilization patterns are lower than in the general Medicaid population, in which over 80% of patients used medical services in the past year (

30). Although there is controversy about the need for an annual physical examination among asymptomatic individuals—and we did not have a specific measure of medical need—it is generally accepted that individuals who are taking a medication for a chronic condition should receive at least one annual medical visit (

24,

25). This poor utilization is particularly concerning given the increased morbidity and mortality documented in this vulnerable population (

1,

6,

8,

9,

12,

13).

Individuals with serious mental illness in rural counties had the lowest utilization, with 58% not accessing outpatient general medical services during the study year. Similar to prior studies, this study found that young adults, men, blacks, individuals with schizophrenia, and individuals with comorbid drug and alcohol use disorders were less likely to have an outpatient general medical visit (

1,

16,

17,

31–

33). These differences in use of outpatient medical services were seen even though all individuals in the cohort had the same insurance (Medicaid). The fact that people with schizophrenia were less likely to use outpatient care than those with other disorders is especially concerning, given that a recent study found that adults with schizophrenia were more than 3.5 times as likely (all-cause standardized mortality ratio) to die at younger ages than those in the general population, primarily from cardiovascular and respiratory diseases (

1). Of note, this excess cardiovascular mortality was seen even among young adults (ages 20–34).

This lack of use of outpatient general medical care has implications for preventive service delivery for individuals with serious mental illness. For example, because many antipsychotic medications are associated with metabolic syndrome (

8,

34), the American Diabetes Association and the American Psychiatric Association issued guidelines in 2004 for monitoring metabolic risk factors. Unfortunately, prior studies have found that even ten years after these guidelines were published, only 30% of individuals taking these medications were being screened for diabetes (

3,

18). Part of the problem is that community mental health clinics often do not have established referral and treatment options (

35). Another contributing factor may be that few primary care providers may know about monitoring and treatment guidelines for individuals taking antipsychotic medications (

36). Unfortunately, there are no clear standards for the delineation of responsibilities between mental health and primary care providers regarding baseline and maintenance monitoring and treatment for metabolic side effects of these medications (

3,

35).

Notably, because our study included only individuals who are engaged in the public mental health care system, it is likely that our findings underestimate the extent of this problem. People with serious mental illness have difficulty engaging in specialty mental health services (

4,

7). In fact, the California Department of Health and Human Services estimated that in 2012 only 22% of Medicaid-enrolled individuals with serious mental illness in the state were engaged in specialty mental health services (

37). The large number of individuals with serious mental illness without outpatient general medical visits highlights the importance of initiatives to integrate care to improve the fragmented mental and general medical health care system (

21,

35).

Despite an Institute of Medicine call for improved integration of general medical and mental health care for individuals with serious mental illness (

4), a recent Cochrane review noted a lack of studies examining effective collaborative care for people with schizophrenia (

38). The lack of integration (cultural, fiscal, geographic, and electronic) among primary care and mental health systems obviously represents a barrier to coordinated services for this vulnerable population (

21,

35,

39). Models of care have been developed that facilitate collaboration and coordination between mental health and general medical clinics to improve morbidity and reduce mortality among individuals with serious mental illness (

40), but these models have proven difficult to disseminate. Dissemination will require structured support, concerted leadership, and financial restructuring.

There were several limitations to this study. First, our models used administrative billing data, with only individual-level predictors included in the model and no place-of-service codes or additional types of service variables. Although we found a difference in outpatient service use in our cohort between individuals with managed Medicaid and those with fee-for-service Medicaid, more research is needed to determine the factors that led to differential access to care between these two groups. Furthermore, the administrative billing data did not include general medical comorbidities, behavioral factors (for example, smoking), area-level social determinants of health, or other personal characteristics that may have influenced the number of outpatient visits. Thus there may have been residual confounding.

The differences in relative risk seen in our cohort were relatively small, suggesting that we may not have captured some of the factors that accounted for whether an individual had at least one outpatient visit. In addition, our results may not be generalizable to individuals with serious mental illness who are not in treatment in community mental health centers or who live in states other than California. Many individuals with serious mental illness do not access specialty mental health services, and those engaged in such care may be more likely to access nonpsychiatric outpatient visits; thus our findings may overestimate the number of individuals with serious mental illness seen in primary care (

37). Our study represented only a subsample of individuals with serious mental illness; however, given the use of antipsychotic medications, this is a subsample of interest. Other systems-level factors not examined in this study may also influence the likelihood of outpatient visits, including case management programs, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations. Although individuals who receive acute services (such as urgent care, emergency room care, and hospitalization) should also receive subsequent outpatient services, information about use of these types of services was not available for our cohort.