Approximately 20% of children living in the United States experience a mental health problem severe enough to require treatment (

1), yet 80% never access services (

2). Among the 20% who initially engage in treatment, up to 80% drop out of care before receiving an effective therapeutic dosage (

3). This problem is exacerbated among children living in poverty, who are at an elevated risk for serious mental health problems, including disruptive behavior and oppositional defiant disorders. This is due, in part, to living in communities with scarce resources and stressors including community violence and crime, drug accessibility, unstable housing, unemployment, and food insecurity (

2–

4). The consequences associated with not receiving treatment during childhood are considerable: Not only are many mental health conditions associated with impairments in academic, behavioral, and social functioning, but they are also often chronic and likely to extend into adulthood (

5). Furthermore, families of children with disruptive behavior disorders face additional challenges in engagement and utilization of child mental health services (

6).

It is commonly understood that caregivers play a pivotal role in the receipt of child mental health services (

7), and theories of help seeking identify multiple impediments that caregivers can encounter that block engagement in and ongoing utilization of child mental health services (

8). Staudt (

9) identified the following to influence receipt of services: family stressors, logistical or external obstacles, cost, schedule conflicts, and caregiver therapeutic alliance with the provider. Ingoldsby (

3) added provider- and organizational-level factors, including agency wait lists, staff turnover, geographic location, and language, which can also affect service receipt among youths. McKay and Bannon (

4) argued that perceptual barriers are particularly impeding for families, including stigma and negative views about mental health and the treatment system.

The rationale for undertaking this study is to identify barriers to ongoing use of mental health services experienced by the most vulnerable and high-risk families to direct service efforts toward retaining families in treatment and improving child mental health outcomes. Additionally, few studies to date have examined the subscales of the barriers to treatment measure described in the following section.

Methods

Data were obtained from the 4Rs and 2Ss Program for Strengthening Families (4R2S) multiple-family group field trial of caregivers of children between seven and 11 years of age with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Participants were recruited from 13 public child mental health outpatient clinics licensed by the New York State Office of Mental Health and included adults age 18 years or older who spoke English or Spanish. New York University’s Institutional Review Board provided approval for this study. The present study examined barriers to treatment and session attendance among those in the experimental condition (N=225). The 4R2S is a manualized, time-limited (16 weeks, 90–120 minutes per session) mental health intervention targeting school-age, urban youths who meet diagnostic criteria for ODD and their families, delivered in both English and Spanish. The intervention includes the following core components: roles, responsibilities, relationships, and respectful communication, along with social support and stress; for a full description, see Chacko et al. (

10).

Demographic characteristics were collected via a general sociodemographic questionnaire at baseline, and attendance in 4R2S groups were recorded weekly. Because of low base rates of completion (N=22 [10%] attended all sessions), differences according to sample groups of completion status could not be examined. Therefore, as a marker, we used “attended seven or fewer sessions versus eight or more,” consistent with previous literature in which eight or more sessions is needed to obtain a therapeutic effect in community health settings (

11). The majority of the sample attended eight or more sessions (N=144, 64%), and, on average, participants attended nine sessions (i.e., completed roughly 60% of treatment).

Barriers to treatment were measured using Kazdin et al.’s Barriers to Treatment Participation Scale (KBT) (

12) at posttest (16 weeks after baseline; N=173). Few studies to date have examined subscales of the KBT, a self-report measure completed by parents that assesses factors that affect family participation and attendance. Subscales include stressors and obstacles that compete with treatment, perceived relevance of treatment, relationship with therapist, treatment demands and issues, and critical events. All subscales except the critical events subscale, were rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 5 with the following anchors: never a problem, once in a while, sometimes a problem, often a problem, and very often a problem. The critical events subscale items were rated on a binary scale reflecting the absence or presence of each critical event. Higher scores in all subscales indicate greater presence of barriers to treatment. Cronbach’s alphas at posttest range from .50 to .86 for all subscales at posttest.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 24 and Mplus7 to examine the relationships between demographics, barriers to treatment utilization, and attendance. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was preformed to examine the relationships between critical life event items that interfere with treatment and sessions attended using a robust (Huber-White) maximum-likelihood algorithm to deal with nonnormality and variance heterogeneity. Endogenous variables independently included the critical events subscale items at posttest; the dichotomous endogenous variable included sessions attended (seven or fewer sessions versus eight or more); and covariates included parent age, primary caregiver, and family income. The fit of the SEM model was evaluated using both global and focused fit indices.

Results

Children were a mean±SD age of 8.88±1.45, were most often male (N=148, 66%), and were identified as black or African American (N=66, 30%) or Hispanic/Latino (N=112, 50%). Caregivers were 35.72±8.39 years old, and most reported being the child’s mother (N=175, 78%). Most often, caregivers identified as black or African American (N=63, 28%) or as Hispanic/Latino (N=119, 53%) and reported being married (N=81, 36%) or single (N=86, 38%). The majority reported having less than a high school education (N=87, 39%), a high school education (N=50, 23%), or some college education (N=49, 22%). Caregivers were most often employed full-time (N=54, 24%) or unemployed (N=71, 32%), reported an annual family income of less than $9,999 a year (N=91, 40%) or $10,000–$19,999 a year (N=55, 24%), and reported receiving Medicaid (N=144, 64%). Caregivers who attended eight or more sessions were significantly older (36.9±8.9) than caregivers who attended seven or fewer sessions (33.5±6.6) (t=−2.89, df=215, p<.01).

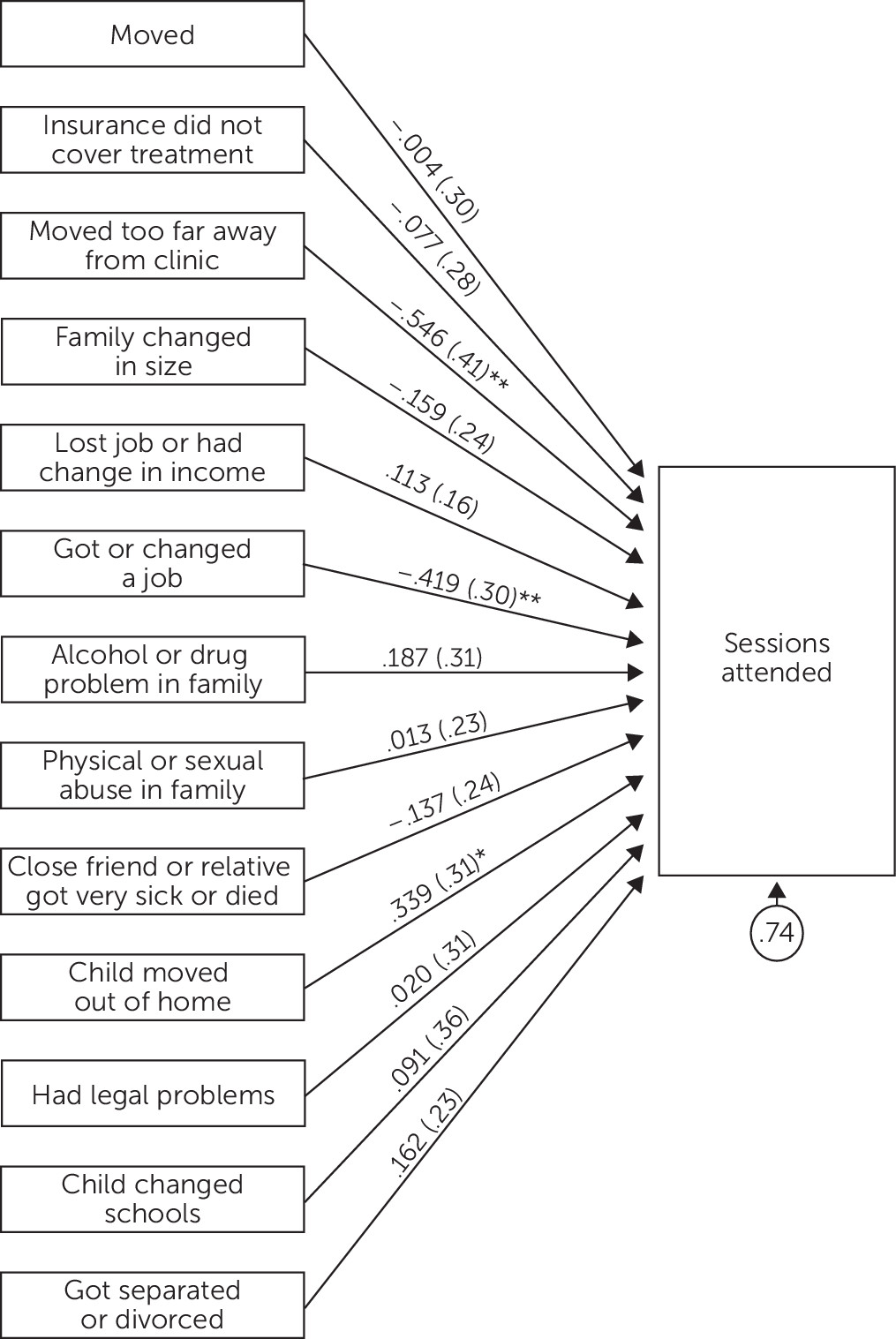

Scores for caregivers’ competing stressors and obstacles were significantly greater among participants who attended seven or fewer sessions (33.56±12.15) than among those who attended eight or more sessions (27.75±9.16) (t=3.23, df=171, p<.01). Additionally, caregivers who attended seven or fewer sessions endorsed having experienced significantly more critical events (1.41±1.53) than participants who attended eight or more sessions (.9±81.18) (t=2.21, df=171, p<.05). The four most commonly experienced critical events were: losing a job or having a change in income (N=30, 13%), having a close friend or relative become ill or pass away during the time of treatment (N=24, 11%), family size change (i.e., having another baby or someone moving in or out; N=21, 9%), and moving during the time of treatment (N=18, 8%).

Global fit indices of sessions attended and critical events model pointed toward good fit: χ2=6.58, df=5, p=.254; comparative fit index=.97; root mean square error of approximation=.037, p value for the test of close fit=.54; and standardized root mean square residual=.015. An examination of focused fit indices (standardized residuals and modification indices) revealed no theoretically meaningful points of stress on the model.

Figure 1 presents the unstandardized parameter estimates for the model, with margins of error given in parentheses. For caregivers who endorsed moving too far away from the clinic, on average, there was a 55% decrease in the likelihood of attending eight or more sessions holding all other variables constant (b=−.546, margin of error (MOE)=.414, p<.01). For caregivers who endorsed having a job change, on average, there was a 42% decrease in the likelihood of attending eight or more sessions holding all other variables constant (b=−.419, MOE=.298, p<.01). Last, for caregivers who endorsed that the child moved out of the home, on average, there was a 34% increase in the likelihood of attending eight or more sessions holding all other variables constant (b=.339, MOE=.310, p<.05).

Discussion and Conclusions

Findings indicated that families who attended seven or fewer sessions reported more competing stressors and obstacles, compared with those families who attended eight or more sessions. Critical events endorsed by those families attending seven or fewer sessions primarily align with practical obstacles to treatment rather than attitudes about treatment demands, beliefs about treatment, relevance, or therapist alliance (

9,

12). These findings are consistent with those of Harrison et al. (

13), in which conflicting demands on caregivers’ time often hindered families from attending outpatient child mental health treatment. Interestingly, a child moving out of the home was related to increased likelihood of treatment attendance, and there were no significant relationships between barriers to treatment and attendance by racial, ethnic, income, or health insurance categories in the present study.

As can be seen in this study, the competing stressors and obstacles commonly experienced by low-income families (

13) continue to hinder the ability of families to receive a sufficient dosage (as established in the child mental health literature) of treatment. To address such issues, child mental health programs may consider modifications to program characteristics to better fit the needs of the population they serve. Family support services, in contrast to standard/traditional children’s mental health services, focus on assisting caregivers in identifying their specific concerns or needs, providing an array of supportive services (e.g., information, skill development, advocacy, system navigation, outreach, linkage to concrete services), and encouraging caregivers to become actively involved in children’s treatment (

14). Offered as an augmentation to standard treatment, family support services could take the form of case management services delivered by family peer advocates focused on reducing the logistical barriers to treatment as well as addressing family stressors. Alternately, child mental health programs may also consider technological advances to increase access to and participation in treatment. With the recent emergence of psychotherapeutic treatment utilizing the Internet (known as e-therapy, online therapy, Internet therapy, e-health, and telehealth), online treatment holds the potential of overcoming common logistical barriers such as lack of providers, geography, and transportation by providing greater service delivery flexibility (

15).

The limitations of this study are important to note. First, the assessment of barriers relies on caregiver report alone and may be affected by reporter bias. Second, other factors not assessed in this study contribute to these findings, given that all predictors accounted for 26.4% of the variance in sessions attended. Third, treatment attendance was the sole focus here, yet engagement may be manifested through behavioral, affective, and cognitive indicators (

9). Fourth, although the literature demonstrates a marker of eight or more sessions (

11), the exact number of sessions within 4R2S needed to meet a therapeutic effect is not established and should be investigated in future research. Fifth, organizational- and provider-level factors were not assessed in this study and can be related to barriers to treatment and attendance. Last, causality cannot be implied, given that this study is cross-sectional in nature.

Child mental health programs serving low-income families struggling with treatment engagement may want to consider structural modifications that allow for greater family support as well as greater flexibility in treatment delivery, such as leveraging recent technological advances.