The field of homelessness services has evolved beyond stepwise housing approaches in which clients start in restrictive, dependent housing settings and progress to increasingly less restrictive and independent settings (

1). The current predominant housing approach for adults who experience chronic homelessness is the Housing First model, which aims to provide immediate, independent, permanent housing with no required prerequisites, such as sobriety or treatment adherence (

2). The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has officially adopted the Housing First model for its permanent supportive housing program, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development–VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) program (

3). The HUD-VASH program provides subsidized rent and case management to help veterans acquire and retain permanent independent housing. The VA’s Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) program, which provides homelessness prevention and rapid rehousing services, also operates under a Housing First approach.

The VA has been dedicated to preventing and ending homelessness among veterans for nearly a decade and has made substantial progress, with a 45% reduction between 2009 and 2017 in the number of veterans experiencing homelessness on a given night (

4). Although the HUD-VASH and SSVF programs have been two of the main vehicles to end veteran homelessness, the VA maintains a continuum of homelessness programs to serve the diverse needs of veterans who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. The VA does not use a “one size fits all” approach to homelessness services, because studies have shown that a range of services are needed to meet the complex housing, health, and social needs of this population (

5,

6). The VA’s housing continuum includes various specialized homelessness assistance programs, including domiciliary care, transitional housing, permanent supportive housing, homelessness prevention, rapid rehousing, and other supports.

Use of the VA’s continuum of homelessness programs is not well understood, including whether differences exist between single and multiple program users and whether there are patterns in the timing and duration by which different VA homelessness programs are used. Prior research, often cross-sectional studies, has examined the characteristics, service use, and housing outcomes of veterans participating in individual VA homelessness programs (

5,

7,

8). However, examining participation in these programs in isolation ignores the fact that veterans are likely to be eligible for (and may access) multiple programs over time. In addition, cross-sectional examination does not capture the sequence and timing of how veterans use various programs. Thus it is important to analyze longitudinal data on use of all VA homelessness programs together to understand how veterans may use programs together, the sequence in which these programs are used, and for what periods.

In the study reported here, we aimed to identify temporal typologies and pathways to veterans’ use of various VA homelessness programs and examine how different utilization patterns of VA homelessness services are associated with veterans’ characteristics and use of VA health services. To our knowledge, this is the first national study to profile how veterans use multiple VA homelessness programs over time. In the era of the Housing First model, the results may inform development and program planning for an array of VA homelessness services.

Methods

Data Source

This project used administrative data from 2014 to 2017 from three VA data sources that were merged for analysis. First, we obtained records from the Homeless Operations Management and Evaluation System (HOMES), which collects veteran-level information about use of various VA homelessness programs. HOMES includes sociodemographic information for all veterans who access the above-described programs and also provides entry and exit dates for all these programs as well as information about a veteran’s housing destination at the time of his or her exit from each program. Second, we obtained data from the SSVF program. The SSVF program provides grants to community-based organizations to provide homelessness prevention and rapid rehousing to veterans who are at risk of or are currently experiencing homelessness and their family members. SSVF program data include demographic information for program participants as well as entry and exit dates and information about a veteran’s housing destination at exit from the SSVF program. Third, we obtained data from VA electronic medical records through the VA’s Corporate Data Warehouse to capture veterans’ inpatient and outpatient service use in the VA health care system. Because this study was designated a VA operations project, it was deemed exempt from institutional review board approval.

Data Analysis

The SSVF and HOMES data were used to select the sample for this study, which included all 61,040 veterans who entered any of the above-described VA homelessness programs at some point during the first three quarters of federal fiscal year 2015 (i.e., between October 1, 2014, and June 30, 2015) and who had no record of VA homelessness service use at any point in the prior 12 months. We used this period to select the cohort because the SSVF program expanded dramatically between its introduction in federal fiscal year 2012 and the beginning of federal fiscal year 2015. Fiscal year 2015 was the first year in which SSVF services were available in virtually all (96%) HUD Continuums of Care, which are the jurisdictional units used by HUD in administering federal homelessness assistance dollars (

9). We used this 9-month period to select the cohort because at the time of completion of this study, SSVF and HOMES data were available only through June 30, 2017, and thus our sample selection criteria allowed for a uniform 2-year follow-up period for all veterans in the study cohort.

In following prior research on the temporal dynamics of emergency shelter use (

10), we used an analytic approach known as sequence analysis to examine patterns of VA homelessness program use over time. We separated the 2-year period following each veteran’s initial entry into a VA homelessness program into 24 discrete 1-month periods. We then assessed whether veterans participated in any of the following seven VA homelessness programs during each month: Contract Residential or Safe Haven, Domiciliary Care for Homeless Veterans or Compensated Work-Therapy/Transitional Residence, Grant and Per Diem program (GPD), Health Care for Homeless Veterans Case Management, HUD-VASH, SSVF prevention, and SSVF rapid rehousing.

Table 1 provides a brief description of each of these programs. We also assessed whether veterans participated in multiple programs during the same month (i.e., any combination of two or more of the seven programs in the same month). This approach resulted in a unique sequence of VA homelessness program use for each veteran in the study cohort over the 24-month period.

After creating sequences for each veteran, we used optimal matching (OM) (

11) to compare the VA homelessness program sequences of each veteran in the study cohort to all other veterans in the cohort. OM provides a single summary measure of the extent to which each veteran’s sequence is similar to or different from those of all other veterans. This distance measure is used to form a large N × N dissimilarity matrix (i.e., one row/column for each veteran pairing), and we used this dissimilarity matrix for a cluster analysis classifying veterans into different profiles with similar sequences of VA homelessness program use. Specifically, we employed hierarchical clustering by using Ward’s method.

Conducting cluster analysis on a large data set of the type used for this study requires significant computing power, and we were unable to successfully conduct cluster analysis for the full data set by using the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (

12), which is the computing environment we used for all analyses. Because of these computational challenges, we selected a random subsample of 25% of the full cohort (N=15,260) to serve as the primary analytic sample in conducting the cluster analysis. We replicated the cluster analysis for another randomly selected 25% subsample, and the results were consistent; thus we present only the results of our original cluster analysis.

After conducting cluster analyses, we compared the identified profiles on sociodemographic variables (age, sex, race, and ethnicity), last known housing status, and use of VA health care services over the 2-year study period by using bivariate analysis of variance and chi-square tests. Finally, multivariable analyses were conducted by using multinomial logistic regression, comparing profiles on sociodemographic variables, last known housing status, and use of VA health care services. Because of the multiple comparisons and statistical power from the sample sizes, we focused on differences significant at the p<.001 level.

Results

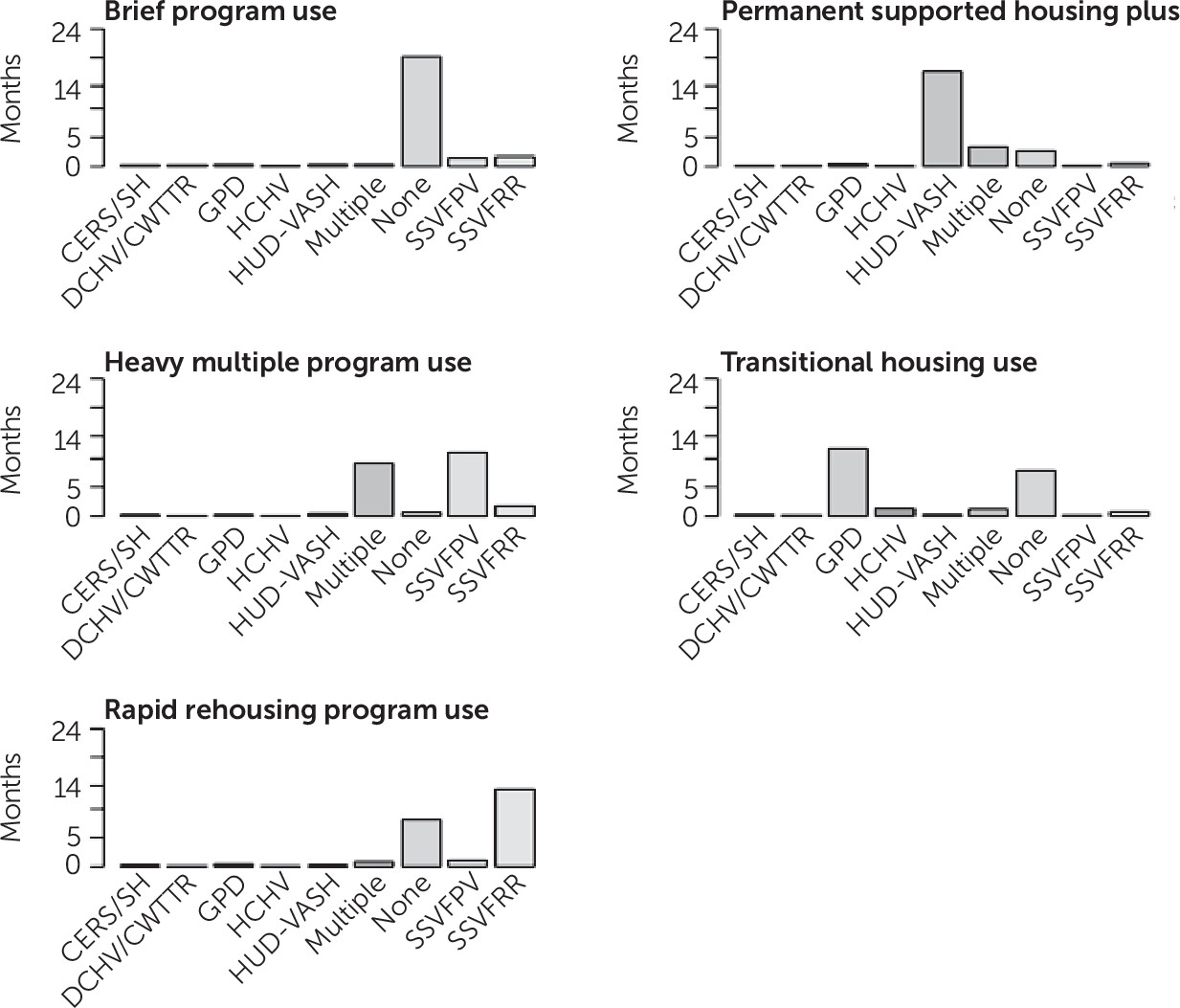

Our analysis identified five distinct profiles of VA homelessness program use over time. (See the

online supplement.) The profiles were labeled brief program use (N=9,019), permanent supported housing plus (N=3,262), heavy multiple program use (N=518), transitional housing use (N=981), and rapid rehousing program use (N=1,480).

Figure 1 plots the number of months during the 24-month study period that, on average, veterans in each profile participated in each VA homelessness program.

The brief program use profile was the largest profile comprising 59.1% of veterans in the total analytic sample. This profile group consisted of veterans who typically made one-time and relatively brief use of VA homelessness programs. The specific programs in which veterans in this group participated varied, but the SSVF prevention and SSVF rapid rehousing programs accounted for the single largest share. Veterans in this group did not have any record of participating in a VA homelessness program for the majority of the 24-month study period, and only a small fraction of veterans in this group remained involved in a VA homelessness program of any type for more than 10 months following the initial date of their entry into a program.

The permanent supported housing plus profile was the second largest profile, accounting for 21% of the total analytic sample. Veterans in this profile group were characterized primarily by their long-term use of the HUD-VASH program, often in conjunction with a second VA homelessness program during the same month. Indeed, veterans in this group spent, on average, more than half of the 24-month study period in HUD-VASH. The proportion of veterans participating in multiple programs decreased over time, suggesting that veterans ceased their involvement in other programs as they transitioned into and stabilized in permanent supportive housing through HUD-VASH.

The heavy multiple program use profile was the smallest profile, accounting for only 3% of the analytic sample. Veterans in this profile group were characterized by their heavy involvement in multiple VA homelessness programs over the entire course of the study period. In each month of the study period, there were roughly equal proportions of this group were involved in multiple VA homelessness programs.

The transitional housing use profile accounted for 6% of the analytic sample. Veterans in this profile group were characterized by their heavy use of the GPD program, particularly in the first half of the 24-month study period. The proportion of veterans in this group participating in GPD decreased steadily over the study period, with only a small proportion still in GPD at the end of the study period, suggesting a pattern of veterans transitioning out of GPD over time.

The rapid rehousing program use profile accounted for 10% of veterans in the analytic sample. This group comprised primarily veterans who participated in the SSVF rapid rehousing program for an extended period, particularly in the first half of the 24-month study period. Veterans in this group received SSVF rapid rehousing services for about half of the months in the study period on average.

Table 2 presents data comparing background characteristics and VA service use for veterans in the five profiles. Veterans in all profiles were, on average, about 50 years old, and most were male. The heavy program use profile had the highest proportion of females, and the transitional housing use profile had the lowest. There were notable profile differences with respect to race, with the brief use profile having the highest proportion of white veterans and the heavy program use profile having the lowest proportion.

With respect to VA health care service use, no significant differences across profiles were found in terms of inpatient general medical or substance abuse treatment visits. However, there was a trend that the permanent supported housing plus and transitional housing use profiles had more inpatient mental health visits (an average of about 3 days over the 2-year study period) compared with other profiles (p<.05). A similar pattern was seen with respect to outpatient general medical (p=.03) and outpatient mental health (p=.05) services use, with the permanent supported housing plus and transitional housing use profiles having more visits of each type compared with the other profiles.

Table 3 presents data on the last known housing status of veterans in each profile. There were clear differences between profiles with respect to this outcome. On one end, nearly two-thirds of those in the brief program use profile exited a homelessness program for a permanent housing destination (which does not include HUD-VASH) during the study period. On the other end, nearly all of those in the heavy multiple program use profile were still involved in a VA homelessness program at the end of the 2-year observation period.

Table 4 shows results of a multivariable analysis comparing background characteristics, last known housing status, and VA health service use between profiles. Significant differences were noted between profiles on age, gender, race, last known housing status, and VA inpatient and outpatient health care service use. Most notably, the transitional housing profile was least likely to have women, and the brief use and transitional housing profiles had the highest proportion of white veterans. Those in the supported housing plus and brief use profiles were most likely to be in permanent housing at their last known housing status, assuming most who were still in a program in the supported housing plus group were housed in HUD-VASH. Of note, over 40% of both those in the transitional housing and rapid rehousing profile were in permanent housing at their last known housing status. In terms of VA health service use, those in the supported housing plus profile tended to have the greatest service use across inpatient and outpatient general medical and mental health services. Those in the transitional housing group were more likely to have outpatient substance abuse treatment services, but no significant differences were found between profiles in use of inpatient substance abuse treatment services.

Discussion and Conclusions

This national study illustrated how a continuum of homelessness services was used within the largest integrated health care network in the United States. Although the Housing First model has been adopted by the VA health care system and other homelessness service providers, many comprehensive health care and social service systems still operate a continuum of housing options for clients. Results of this study shed light on how the VA’s array of housing programs and services are used by a heterogeneous group of veterans with varying housing and social needs. Analysis of data on VA service use from 15,000 homeless veterans over a 2-year period revealed five profiles of homelessness program use: two profiles reflected brief program use; a third profile was characterized mostly by use of transitional housing; a fourth involved use of VA’s permanent supportive housing program, along with brief initial use of some other VA homelessness program; and a fifth profile was characterized by heavy use of multiple homelessness programs concurrently.

These profiles point to several notable findings. For one, most homeless veterans used VA homelessness programs only briefly. Over half (59%) of veterans were categorized in the brief program use profile, and 10% were categorized in the rapid rehousing program use profile. Both of these profiles were characterized by involvement in VA homelessness programs for a year or less, on average. A second important finding is although permanent supportive housing is commonly considered a stand-alone program, we found that, in fact, many veterans were enrolled in HUD-VASH while at the same time being enrolled in some other VA homelessness program, presumably because they needed services beyond those provided by HUD-VASH. These other programs included domiciliary care, transitional housing, and the SSVF program. Such multiple program use is likely the result of veterans’ use of one of these other VA homelessness programs as a form of temporary housing while they locate a permanent supportive housing unit in which to use their voucher. The SSVF program can provide security deposits and utility assistance when veterans move into permanent housing. A third noteworthy finding is that a sizable proportion (6%) of veterans were in the transitional housing use profile, meaning that they were able to exit homelessness through transitional housing, which suggests that the Housing First model of permanent supportive housing may not be necessary for all veterans. This may be important to consider in resource allocation and program development because there have been some broad shifts away from transitional housing in the era of Housing First, although many have pointed to the value of a residential continuum of options (

13–

15).

Various groups of homeless veterans tended to use programs differently. Those in the supported housing plus profile used more VA general medical and mental health services, compared with those in other profiles, and the transitional housing profile consisted almost entirely of men. Some findings were fairly well known, such as that female veterans were less likely than male veterans to use transitional housing partly because of lack of transitional housing for females and children but also because of concerns about privacy and safety among female veterans (

16–

18).

Some of these utilization patterns may reflect veterans’ needs and preferences, but others may reflect availability of services and providers’ preferences. It is likely these utilization patterns reflect a combination of factors, including needs, preferences, and availability.

Nonetheless, our findings underscore the need for homelessness service providers to balance various factors in guiding their clients through an array of housing options. Although the Housing First model has been shown to be effective in several randomized trials (

2,

19), providers must consider various factors, such as contending with a limited supply of permanent supportive housing units; eligibility criteria for various homelessness programs; and varying degrees of severity of homelessness, mental illness, and other functional impairments that may affect the housing arrangement needed. Taken together, our findings support the continued development of VA’s continuum of homelessness programs and services for various subgroups of veterans with different levels of need. Moreover, our results provide a comprehensive snapshot of utilization patterns among homeless veterans with diverse housing and social needs.

Several limitations of this study are worth noting. First, our study characterized VA homelessness service utilization within a specific 2-year time frame from 2015 to 2017, and it is unknown whether the results generalize to veterans who used VA homelessness services outside the study period or whether these profiles extend to other homeless adults. For example, the SSVF program is a relatively new program that did not exist before 2013. Therefore, veterans previously did not have access to this program, and many nonveterans may not have access to similar services. Second, our analyses identified certain individual characteristics associated with various patterns of homelessness service use. However, we cannot infer causation and are limited by our data in examining exactly why some veterans had different profiles. In addition, we cannot tease out what aspects of service use were based on client preferences, provider preferences or influence, or other factors (e.g., housing supply). Similarly, our comparison of the background characteristics of veterans across profiles did not include covariates, such as geographic region, behavioral and general medical diagnoses, income, and information related to a veteran’s military service. The inclusion of these covariates would not change the composition of the profile groups we identified but would provide a more nuanced understanding of the characteristics of veterans in each group. Finally, although our analysis provided information about the last known housing status of veterans in each profile group, this should not be interpreted as an indication of the quality or effectiveness of VA homelessness programs. Indeed, our analysis was unable to assess quality or effectiveness of these programs in a meaningful way.

These limitations underscore the need for additional research to better understand factors that influence distinct utilization patterns and how utilization patterns may affect housing- and health-related outcomes. Improved knowledge in these areas could result in more efficient and effective use of systems such as the VA that operate a continuum of homelessness programs and services.