Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a prevalent (

1), disabling (

2), and potentially fatal mental illness, with rates of suicide completion and burden of disease similar to those of schizophrenia (

3,

4). Although only a fraction of individuals with BPD seek psychological or psychiatric care (

5), they remain overrepresented in acute psychiatric care settings, constituting an estimated 9%−22% of outpatient clinic cases (

6,

7) and 20%−25% of inpatient admissions (

7,

8). Costs to society associated with personality disorders have been estimated at $12,696–$19,231 per patient yearly, more than double the costs associated with depression (

9). Given the severity of the disorder, its prevalence in treatment settings, and high associated costs, there is an epidemiological and economic imperative for health systems to be able to address BPD effectively worldwide.

BPD was formerly considered a “wastebasket diagnosis,” given to patients who were thought to be “untreatable” (

10). However, there are now a number of specialist evidence-based treatments for BPD (

11,

12). Specialist evidence-based manualized treatments for BPD include dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) (

13,

14), mentalization-based treatment (MBT) (

15,

16), schema-focused therapy (SFT) (

17,

18), and transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP) (

19,

20). Although psychotherapies are considered the treatment of choice in guidelines for the clinical management of BPD (

21), referral to psychotherapy as a first step of treatment after diagnosis is done only in a minority of cases mainly because of the general insufficient supply of psychotherapists—and especially of those trained in BPD-specific approaches (

22).

Furthermore, the implementation and survival of programs providing psychotherapeutic approaches to BPD (e.g., DBT and MBT) remain fragile (

23–

25). Obstacles to establishing and maintaining treatment programs in the evidence-based treatments for BPD include lack of support by public health authorities or program directors (

25–

28); lack of time, resources, and funds to provide or attend training (

24–

26,

28); difficulty recruiting and retaining staff, as well as staff turnover (

24–

28); lack of capacity and organizational issues (

22,

23,

27,

29); and instability of team dynamics, communication, and supervision (

23,

24,

27,

30,

31). Consequently, teams providing evidence-based treatments for BPD struggle to survive. The probability of a DBT team surviving over 10 years is under 50% (

24,

25).

Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for BPD has not shown that any of the evidence-based psychotherapies are superior to the others or that intensity or duration of treatment is related to outcome (

11). In addition, structured clinical management (SCM) and general psychiatric management (GPM), which are less intensive generalist treatments expressly developed for BPD, have proven effective in attaining symptom reduction in two of the largest methodologically rigorous RCTs for BPD treatment in the literature (

16,

32). SCM proved effective in reducing symptoms of BPD—most notably self-harm—within the first 6 months of treatment but was outpaced by MBT by 18 months (

16). GPM performed as well as DBT across a range of outcomes (

32). However, these approaches have yet to be incorporated in clinical guidelines or algorithms. The quality and quantity of evidence demonstrating superiority of treatments often dictates clinical practice, while feasibility and accessibility considerations are ignored (

33).

The paradox of progress in treating BPD is that effective treatments exist but appear to be available to only a fraction of patients seeking care. To our knowledge, no studies have estimated the supply of and demand for treatment of BPD. Toward that end, this study examined the prevalence of BPD and estimated proportion of individuals with BPD who seek treatment, the total number of mental health care providers who could theoretically provide care for patients with BPD, the number of providers accredited in evidence-based treatments for BPD, and the training and practice requirements for specialist and generalist treatments. The aim was to assess the supply of and demand for treatment of BPD to inform realistic standards of care and training in the context of available resources worldwide.

Results

The total supply of psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers per country in the 22 countries included in the study, the reported supply of clinicians certified in evidence-based treatments, and estimated demand for BPD treatment are summarized in

Table 1. [Raw data are presented in an

online supplement to this article.]

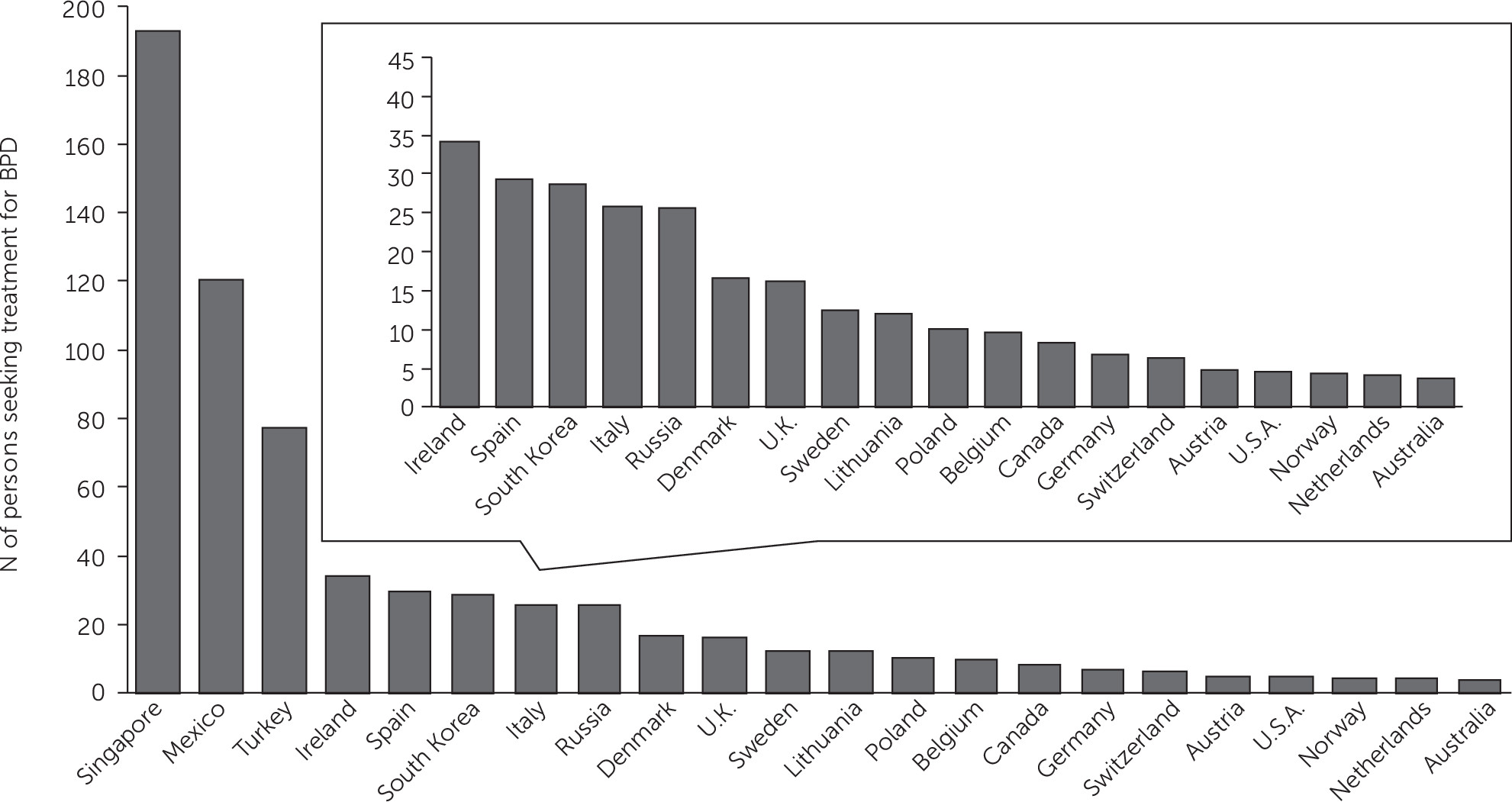

Number of treatment-seeking patients with BPD per mental health care professional ranged from approximately 4:1 in Australia, the Netherlands, and Norway to 192:1 in Singapore (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). Patient-to-provider ratios of under 10:1 were observed for the United States, Austria, Switzerland, Germany, Canada, and Belgium. Provider ratios between 10:1 and 35:1 were observed for all other countries, except Turkey, Mexico, and Singapore, which ranged from 77:1 to 192:1.

Number of treatment-seeking patients per mental health professional certified in evidence-based treatments ranged from 49:1 in Norway to 148,215:1 in Mexico (

Table 1 and

Figure 2). In countries that listed certified DBT teams, ratios of treatment-seeking patients per team ranged from 2,400:1 in the Netherlands to 7,500:1 in Belgium [see

online supplement].

The proportion of each professional’s caseload required to address the demand posed by treatment-seeking patients with BPD ranged from 10% to 567%, assuming the use of a generalist treatment such as SCM or GPM (

Table 1). Caseload requirements would range from 10%−11% (4 hours, four cases weekly per 34–39 cases) in the Netherlands to 494%−567% (198–227 hours, 192 cases weekly per 34–39 cases) in Singapore.

The certification requirements and cost of training for each treatment, as well as standard implementation requirements and cost, are outlined in

Table 2. DBT’s certification procedures differ from country to country and are managed by several organizations internationally affiliated with Behavioral Tech, the primary DBT training organization in North America, founded by the treatment developer Marsha Linehan (

Table 3). Organizations not considered in the table defer to the Linehan Board of Certification (

www.dbt-scandinavia.se) or do not pose explicit certification procedures (

www.asociacionespanoladedbt.com,

www.terapiascontextuales.mx/dbtmexico,

www.dbtrussia.org/dbt_main,

www.ptdbt.pl). MBT, SFT, and TFP have a standard certification procedure internationally.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the supply and demand for BPD treatment, as well as implementation requirements, to consider current standards of care and training in the context of available resources worldwide.

Comparing the number of treatment-seeking individuals with BPD to the total number of mental health care professionals indicated that only a few countries could theoretically address public health needs. In countries with the most adequate supply of mental health professionals (i.e., Australia, the Netherlands, and Norway), if each provider treated approximately four persons with BPD per year, demand for treatment would be met (

Figure 1). However, this ratio assumes that all clinicians accept patients with BPD into their caseload, which is improbable because of an array of possible factors, such as stigma or lack of training (

41–

43). If more clinicians could provide generalist treatment, such as SCM or GPM, this would correspond to 10%−11% of their caseload at minimum, which could theoretically be feasible in only Australia, the Netherlands, Norway, the United States, and Austria, where this number is on par with the estimated BPD prevalence of 9%−22% in outpatient settings (

6,

7). In many other countries, such as Turkey, Mexico, and Singapore, providing even generalist care would be difficult, given the reported total number of mental health care professionals.

In no country considered in this study was the number of certified clinicians sufficient to meet the demand posed by BPD treatment seekers. For example, in Norway, which had the highest number of clinicians certified in evidence-based treatments (

Table 1 and

Figure 2), the ratio was 49:1, corresponding to 61–103 hours a week per clinician. In the Netherlands, the second best-resourced country, the ratio was in excess of 600:1, corresponding to 632–1,296 hours per week per clinician.

It is important to note that the number of certified clinicians is likely a significant underestimate of the total number of clinicians providing DBT, MBT, SFT, and TFP. Many clinicians who are not certified in these modalities have nonetheless received training in specialist treatments and treat BPD. For example, although only 198 clinicians are listed as certified on the Linehan Board of Certification Web site (

www.dbt-lbc.org), more than 1,427 teams have been intensively trained by Behavioral Tech, and more than 55,000 people have received some type of exposure to DBT since 1996 (personal communication, Tony DuBose, Behavioral Tech, October 30, 2018). Similarly, 389 clinicians are listed as certified on the MBT roster (

www.bpc.org.uk/mbt-roster), but 923 have received MBT practitioner training, and 3,846 have received MBT basic training (personal communication, Billie Delaney, Anna Freud Centre, April 3, 2018). The actual number of clinicians providing specialized treatment for BPD likely lies somewhere in between those who have received some training and those who are certified. Either way, it remains clear that there is an insufficient number of clinicians to meet the demand posed by prevalence rates. Certification as a parameter of effective care in today’s public health context may increase quality of care at the expense of quantity and availability of care.

In countries that theoretically have a sufficient number of clinicians to treat BPD, it is unlikely that the clinicians will all become trained in specialized evidence-based treatments for BPD. Not all clinicians are interested in treating, or supported adequately to treat, patients with BPD. Management of other common psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, relies on pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions that tend to be within the skill set of a generalist mental health clinician or even a general practitioner (

44–

46). However, options for pharmacotherapy of BPD are limited (

47), and evidence-based psychotherapies require extensive training (

Table 2) (

48). Further barriers to increasing the supply of care are related to a lack of clinician education and diagnostic training regarding BPD, clinician stigma, and lack of adequate insurance coverage for evidence-based therapies (

43).

Although evidence-based treatments remain the gold standard, they can be considered an option among other approaches that require fewer resources. Generalist approaches, such as SCM (

49) and GPM (

50), may be a good option to help increase capacity to treat BPD, given their lower commitment in terms of training requirements and costs, as well as flexibility in practice (

Table 2). Country-specific guidelines on the treatment of BPD, such as Guideline-Informed Treatment for Personality Disorders (

51) in the Netherlands, also hold promise to increase capacity of health care systems to provide generalist care for BPD by optimizing existing care. Briefer and less intensive treatments can also increase capacity and reduce wait lists, including ten-session good psychiatric management (

52); add-on treatments, such as systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving (

53); or treatments with preliminary support, such as 6-month DBT (

54,

55). Even shorter-term 12-week treatments can be as effective in reducing BPD symptoms as extended treatments lasting up to 24 months (

56).

Given that demand for treatment outstrips supply globally, providing specialist, generalist, pared-down, and remote treatments as needed as part of a stepped care approach (

57–

59) or clinical staging approach (

60) could help facilitate the efficient allocation of limited resources. A stepped care approach would not be dissimilar to that used to structure treatment for many other psychiatric disorders (

61–

63). Models of stepped care can also facilitate transitions through different levels of care (e.g., emergency, inpatient, and outpatient). Such a model has proven effective in Australia, where a “stepped care brief intervention clinic” that facilitated step-down from emergency departments or inpatient units to outpatient care in the community succeeded in both reducing demand for hospital services and yielding cost savings of upwards of $2,500 per patient (

64). Alternative pathways to care that are less circumscribed than intensive evidence-based psychotherapies provide options for patients who do not have the resources, willingness, or ability to engage in a more intensive treatment or who struggle to recover from hospitalizations or step-down from inpatient units.

However, neither generalist approaches to BPD nor a stepped care model will eliminate shortages of or barriers to care (

65). These significant gaps between need for and availability of treatment remain high for most mental health problems (

66,

67). In several of the countries we considered and most countries worldwide, applying the stepped care model described above would not be feasible. Alternative, pared-down approaches, such as psychoeducation (

68), might be more deliverable for subsets of patients in any country, as well as in countries where mental health care is sparse. Remote interventions, such as Web-based psychoeducation (

69) or smartphone applications (

70–

73), could assist in providing some symptom improvement where barriers to treatment cannot be overcome or provider numbers are particularly low. However, in these countries, mental health literacy—that is, basic knowledge about mental illnesses and BPD—is needed for patients to access these resources (

74,

75).

It is important to note six major methodological limitations of this investigation. First, we obtained our estimate of the number of mental health care professionals from the WHO. Some of these data differed from those reported elsewhere by the same government. In the case of Germany, for instance, the German government reported to the WHO that 15,900 medical doctors were providing mental health care nationally, whereas the German Society of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Psychosomatics reported 29,826 (

76). Second, variations in health care systems across countries are likely to give rise to rates of treatment seeking that differ from the 17% statistic (

5) used in this analysis. Although this statistic was drawn from the most rigorous investigation of BPD treatment seeking to our knowledge, a smaller United Kingdom study found somewhat lower rates of treatment seeking through a psychiatrist (8.8%) and a psychologist (4.4%) but higher rates through a general practitioner (GP) (52.7% in the United Kingdom versus 18% in the United States [

5]) in the context of a nationalized health coverage system (

77). In other countries considered in this analysis, ratios of BPD treatment seekers to mental health care providers may thus differ, depending on the role of the GP.

Third, BPD prevalence is likely to vary from country to country because of a range of factors, such as degree of modernization (

78,

79) and the gap between rich and poor (

49). Prevalence estimates range widely from 0.15% in India (

80) to 13% in Turkey (

81). However, these rates are derived from studies with varying degrees of methodological rigor. Fourth, data on accreditation were limited by accuracy of the public registers of accredited and certified clinicians. An attempt was made to reduce these errors by contacting the certifying bodies, some of which provide only partial lists of those willing to be publicly listed, and some of which do not systematically post such information. Fifth, our calculations relied on the maximal caseload of patients with BPD that a clinician could theoretically have. However, realistic clinical guidelines (

51) might recommend no more than 20 personality disorder cases seen on a weekly basis, given the emotional toll of work with this population (

82). Finally, cross-national comparisons were complicated by the fact that certification procedures are not centralized and vary in stringency from country to country (

Table 3). Although the accuracy of these sources appears variable, no publicly available standardized sources of information could serve as an alternative.